gigi

Kindergarten kid

Posts: 1,470

|

Post by gigi on Mar 6, 2009 22:29:58 GMT 1

WARSAW, Poland – A human rights group and Poland's Education Ministry introduced new teaching materials for Poland's middle schools on Thursday in an effort to combat anti-Semitism. That seems to be good news. Hopefully it will have a positive impact. I suppose it will depend on what these children are most influenced by - the attitudes/beliefs of their peers, what they are learning in their own homes, etc. Here is a site I found with some 2007 information about Antisemitism and Racism in Poland: www.tau.ac.il/Anti-Semitism/asw2007/poland.html |

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Mar 14, 2009 21:37:15 GMT 1

Poland not only the land of Holocaust

Polish Radio

25.02.2009

Some 18 thousand high school students from Israel will visit Poland

this year.

The number is far less than in previous years, but the current trips

shall include more meetings of the Israeli youth with their Polish

peers. The organizers have worked hard to create an alternative

picture to that of the homeland of many of their ancestors remembered

only as the place of the Holocaust. According to Jacek Olejnik from

the Museum of History of Polish Jews positive effects have been

achieved thanks to placing the young visitors from Israel in the

homes of their Polish colleagues, instead of tight security hotels.

However, Jacek Olejnik pointed to rapidly rising costs of travel as a

potential factor limiting the number of families who can afford such

trips.

Jewish organizations have estimated that over 70 percent of Jews

scattered all over the world have Polish connections.

Germany gives $1.3 million for Nazi death camp repairs

The Associated Press

Friday, February 27, 2009

BERLIN: Germany will give $1.3 million for badly needed restoration

work at the Auschwitz death camp museum in neighboring Poland.

Foreign Minister Frank-Walter Steinmeier says the donation followed an appeal from Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk to all 27 European Union members to contribute to a fund to preserve the Nazi-built camp. The Polish government says it needs up to €100 million for restoration work at the camp.

Steinmeier said Friday Germany would contribute more in the next

budgetary year and said it would encourage German businesses and private foundations to donate. Tusk's office was not immediately able to comment.

|

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Mar 14, 2009 21:43:57 GMT 1

WARSAW, Poland – A human rights group and Poland's Education Ministry introduced new teaching materials for Poland's middle schools on Thursday in an effort to combat anti-Semitism. That seems to be good news. Hopefully it will have a positive impact. I suppose it will depend on what these children are most influenced by - the attitudes/beliefs of their peers, what they are learning in their own homes, etc. Here is a site I found with some 2007 information about Antisemitism and Racism in Poland: www.tau.ac.il/Anti-Semitism/asw2007/poland.htmlThere are reasonable people in Poland who stand up and protest. Some random quotes from the site:

Most of the 149 racist incidents recorded in Poland in 2007 were antisemitic in nature.

According to Never Again, there were 149 racist incidents in 2007, most of them antisemitic in nature, including cemetery desecrations, antisemitic demonstrations and antisemitic slogans at football matches.

Populist political parties that employed antisemitic rhetoric suffered a defeat in the October 2007 parliamentary election.

Graffiti such as “Gas the Jews” appeared on Lodz schools, buildings, buses and shops on March 14. Some 60 non-Jewish Polish teenagers demonstrated in protest outside the city hall.

In response to a potential compensation deal over Jewish confiscated property in July, Roman Catholic priest Tadeusz Rydzyk, the owner of Radio Maryja, stated: "You know what this is about: Poland giving [the Jews] $65 billion. They will come to you and say, ‘Give me your coat! Take off your trousers! Give me your shoes’." The prime minister’s office condemned the statement and over 600 Polish Catholic intellectuals, journalists, priests and activists signed a letter of protest.

|

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Apr 23, 2009 21:59:20 GMT 1

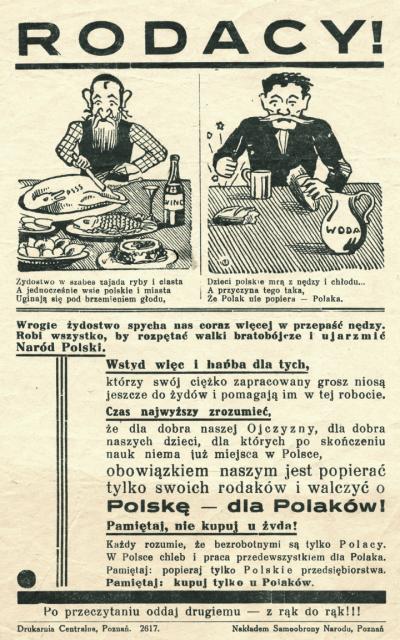

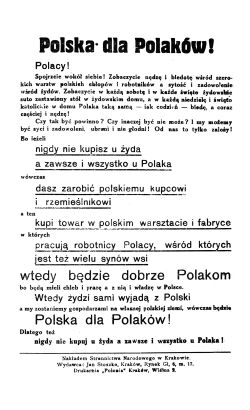

Polish antisemitism before the war. Index books of Jewish students with Ghetto bench seals stamped above the photograph.   upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/a/ab/Index_of_Jewish_student_in_Poland_with_Ghetto_benche_seal_1934.PNG upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/a/ab/Index_of_Jewish_student_in_Poland_with_Ghetto_benche_seal_1934.PNG Ghetto benches or bench Ghetto (known in Polish as Getto ławkowe)[1][2] was a form of official segregation in the seating of students, introduced in Poland's universities beginning in 1935 at Lwow Polytechnic. By 1937, when this practice became conditionally legalized, most rectors at other higher education institutions had adopted this form of segregation. Under the ghetto ławkowe system Jewish university students were forced, under threat of expulsion, to sit in a left-hand side section of the lecture halls reserved exclusively for them. This official policy of enforced segregation was often accompanied by acts of violence directed against Jewish students by members of the Polish fascist organization ONR (delegalised already after three months in 1934) and other pro-fascist organizations. Ghetto benches or bench Ghetto (known in Polish as Getto ławkowe)[1][2] was a form of official segregation in the seating of students, introduced in Poland's universities beginning in 1935 at Lwow Polytechnic. By 1937, when this practice became conditionally legalized, most rectors at other higher education institutions had adopted this form of segregation. Under the ghetto ławkowe system Jewish university students were forced, under threat of expulsion, to sit in a left-hand side section of the lecture halls reserved exclusively for them. This official policy of enforced segregation was often accompanied by acts of violence directed against Jewish students by members of the Polish fascist organization ONR (delegalised already after three months in 1934) and other pro-fascist organizations.

The "bench Ghetto" marked a peak of antisemitism in Poland between the world wars."It antagonized not only Jews, but also many Poles."[6] "Jewish students protested these policies, along with some Poles supporting them... and stood instead of sitting. The segregation continued in force until the invasion of Poland in World War II and Poland's occupation by Nazi Germany suppressed the entire Polish educational system.The demonstration by Polish nationalist students: A Day without Jews! We demand official Ghetto!  Anti Jewish leaflet  Jews to ghetto!  Poland for Poles!  www.rp.pl/artykul/171908_Uczelniane__getta_lawkowe_.htmlwww.zydziwpolsce.edu.pl/panel10.html www.rp.pl/artykul/171908_Uczelniane__getta_lawkowe_.htmlwww.zydziwpolsce.edu.pl/panel10.html |

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on May 22, 2009 21:09:05 GMT 1

Things have changed in Poland, chief rabbi saysShlomo Kapustin

Jewish Tribune

Tuesday, 19 May 2009

TORONTO – Ask most Jews for their impression of Poland and their response could get downright nasty. Even for many young Jews, Poland's history of antisemitism has edged it past Germany in the ignominious race for top historical rogue state. But if the Central European country's chief rabbi is to be believed, that was then; this is now.

"People are realizing that Jews [have been] a part of the country for 1,000 years," said Rabbi Michael Schudrich.

His address, which took place at Beth Habonim Congregation in Toronto last week, was sponsored by the Polish-Jewish Heritage Foundation of Canada and the March of the Living. About 300 people attended.

he New-York-born rabbi was ordained by the Jewish Theological Seminary and later by Yeshiva University. Appointed to his post in December 2004, he traces the new attitude towards Jews to the fall of Communism. Suddenly, Rabbi Schudrich said, "people now feel safe telling their grandchildren and children who they really are."

Poland's Jewish community once took pride in its scholarship – the famous scholar Rabbi Moshe Isserles lived in Kracow in the 16th century – and it numbered 3.5 million on the eve of the Holocaust. While 90 per cent of the community were murdered in the Holocaust, about 350,000 Polish Jews were spared. The vast majority have since emigrated from Poland, but those who opted to stay hid their identity – in many cases, even from their children.

Two major developments are at the root of the sea change in Polish sentiment, said Rabbi Schudrich.

The first is Pope John Paul II, who "did more to effectively fight antisemitism than anyone in 2,000 years." Witness the former pope's celebrated speech at Yad Vashem nine years ago, Rabbi Schudrich said, and contrast it to the current pope's much-criticized efforts at rapprochement with the Jewish community last week (see pages 1 & 5).

The second, he said, is today's Poles' general rejection of the past. And along with their turning from Communism and Fascism has come a spurning of antisemitism, or "anti-antisemitism. "

In fact, Rabbi Schudrich said, two Polish non-governmental organizations – Never Again and Open Society – are dedicated just to fighting it.

This happy confluence of events has kept the rabbi busy – and increased his repertoire of entertaining, even bizarre, stories.

Take the tale of a certain Polish couple. At 20, the woman discovered her Jewish roots, but it wasn't until she turned 23 that she decided to make Friday-night dinner. Her husband went along with the new lifestyle, but his parents were furious. Their son was baffled at his parents' attitude until they too revealed their Jewish roots.

But that is not even the story's punchline. For that, you have to return in time to the early '90s, when the two classmates were high-school sweethearts in Warsaw – and skinheads.

Now, at 33, the happily married couple is active in the community.

As well as his work with those returning to their roots, Rabbi Schudrich is a key liaison to government figures who need insight into Jewish concerns and a prime source for non-Jews about all things Jewish. Just recently, he said, he met with a group of teachers who wanted to learn about Jewish culture.

Much of his time, though, is spent trying to restore cemeteries.

"We have had tremendous success," he said, "but not always."

Some of the many Polish expatriates in attendance still bear animosity to their former home country. One questioner focused on the issue of confiscated property. While the Jewish community has been given the right to claim communal property – a process Rabbi Schudrich described as "too slow, but it is working" – private property that was confiscated from Jews has no such remedy.

Rabbi Schudrich acknowledged that the problem "needs to be fixed," but he clarified that this lack of "reprivatization" is not aimed at Jews. Anyone whose land has been confiscated – by Nazis, by Communists – cannot reclaim it at the moment.

Another questioner took issue with the entire premise of a revitalized Jewish community in Poland. Why doesn't everyone move to Israel? she asked.

"Jews in Poland think a lot about Israel," Poland's chief rabbi said. Many have indeed moved there.

"[But] my responsibility is to teach the people living in my community.… If they are living in Poland they should live as Jews."

----------------------------------------------------------------------

Hitler's European Holocaust Helpers

Spiegel Online

5/20/09

The Germans are responsible for the industrial-scale mass murder of 6 million Jews. But the collusion of other European countries in the Holocaust has received surprisingly little attention until recently. The trial of John Demjanjuk is set to throw a spotlight on Hitler's foreign helpers.

He's been here before, in this country of perpetrators. He saw this country collapse. He was 25 at the time and his Christian name was Ivan, not John; not yet.

Ivan Demjanjuk served as a guard in Flossenbürg concentration camp until shortly before the end of World War II. He had been transferred there from the SS death camp in Sobibor in present-day Poland. He was Ukrainian, and he was a Travniki, one of the 5,000 men who helped Germany's Nazi regime commit the crime of the millennium -- the murder of all the Jews in Europe, the "Final Solution."

He was part of it, if only a very minor cog in the vast machinery of murder. Ivan Demjanjuk stayed in post-war Germany for seven years before he emigrated to the US in 1952 with his wife and daughter on board the General Haan. Once he arrived, he changed his name to John. His time as a supposed DP or "displaced person," as the Anglo-American victors called people made homeless by the war, was over.

DP Demjanjuk had lived in the southern German towns of Landshut and Regensburg where he worked for the US Army. He moved to Ulm, Ellwangen, Bad Reichenhall, and finally to Feldafing on Lake Starnberg. Feldafing belongs to the area covered by the Munich district court, which is why Demjanjuk has been sitting in Munich's Stadelheim prison since he was deported from the US last week. His cell measures 24 square meters, which is extraordinarily spacious by usual prison standards.

Last Big Nazi Trial in Germany

He faces charges of aiding and abetting the murder of at least 29,000 Jews in Sobibor. The trial could start in late summer, provided Demjanjuk, now almost 90, is deemed fit to stand trial. Witnesses will be called to testify, but none of them will be able to identify him. The only evidence lies in the files, but that evidence is strong. Twice, in 1949 and 1979, former Travniki Ignat Danilchenko, who is now dead, stated that Demjanjuk had been an "experienced and efficient guard" who had driven Jews into the gas chambers -- "that was daily work."

Demjanjuk has denied this charge throughout. He says he was never in Flossenbürg or in Sobibor, never pushed people into the gas chambers. The ex-American has adopted the same tactic of denial as many other defendants who stood trial for war crimes after 1945.

The Holocaust in numbers.

DER SPIEGEL

The Holocaust in numbers.

But it's already clear that this last big Nazi trial in Germany will be a deeply extraordinary one because it will for the first time put the foreign perpetrators in the spotlight of world publicity. They are men who have until now received surprisingly little attention -- Ukrainian gendarmes and Latvian auxiliary police, Romanian soldiers or Hungarian railway workers. Polish farmers, Dutch land registry officials, French mayors, Norwegian ministers, Italian soldiers -- they all took part in Germany's Holocaust.

Experts such as Dieter Pohl of the German Institute for Contemporary History estimate that more than 200,000 non-Germans -- about as many as Germans and Austrians -- "prepared, carried out and assisted in acts of murder." And often they were every bit as cold-blooded as Hitler's henchmen.

Just for example, on June 27, 1941, a colonel in the staff of the Germany's Northern Army Group in the Lithuanian city of Kaunas passed a petrol station surrounded by a crowd of people. There were shouts of bravo and clapping, mothers raised their children to give them a better view. The officer stepped closer and later wrote down what he had seen. "On the concrete courtyard there was blonde man aged around 25, of medium height, who was taking a rest and supporting himself on a wooden club which was as thick as an arm and went up to his chest. At his feet lay 15, 20 people who were dead or dying. Water poured from a hose and washed the blood into a drain."

The soldier continued: "Just a few paces behind this man stood around 20 men who -- guarded by several armed civilians -- awaited their gruesome execution in silent submission. Beckoned with a curt wave, the next one stepped up silently and was (…) beaten to death with the wooden club, and every blow met with enthusiastic cheers from the audience."

Orgy of Murder Like a Lithuanian National Ceremony

When all lay dead on the ground, the blonde murderer climbed on the heap of corpses and played the accordion. His audience sang the Lithuanian anthem as if the orgy of murder had been a national ceremony.

How could something like that happen? For a long time now, this question hasn't just been directed at the Germans, whose central responsibility for the horror is undisputed -- but also at the perpetrators in all countries.

What led Romanian dictator Ion Antonescu and his generals, soldiers, civil servants and farmers to murder 200,000 Jews (and possibly twice that many) "of their own accord," as historian Armin Heinen puts it. Why did Baltic death squadrons commit murder on German orders in Latvia, Lithuania, Belarus and Ukraine? And why did German Einsatzgruppen -- paramilitary "intervention groups" operated by the SS -- have such an easy time encouraging the non-Jewish population to wage pogroms between Warsaw and Minsk?

It's completely undisputed that the Holocaust would never have happened without Hitler, SS Chief Heinrich Himmler and the many, many other Germans. But it's also certain "that the Germans on their own wouldn't have been able to carry out the murder of millions of European Jews," says Hamburg-based historian Michael Wild.

It's a perception that many survivors never doubted. When the Association of Surviving Lithuanian Jews convened in Munich in 1947, they passed a resolution that bore an unmistakable title: "On the guilt of a large part of the Lithuanian population for the murder of Lithuania's Jews."

In the Third Reich with its well-functioning bureaucracy, there were comprehensive registers of the Jewish population. But in the territories conquered by the German army, Hitler's henchmen needed information of the type supplied in the Netherlands by registry offices whose staff went to a lot of trouble to compile a precise "Register of Jews."

And how would the SS and police have been able to track down Jews in the cities of Eastern Europe with their broad mix of ethnic groups if they hadn't had the support of the local population? Not many Germans would have been able "to recognize a Jew in a crowd," recalls Thomas Blatt, a survivor of Sobibor who wants to testify as a witness at Demjanjuk's trial.

At the time, Blatt was a blonde-haired boy and tried to pass for a Christian child in his Polish home town of Izbica. He didn't wear a yellow star and tried to appear self-confident when he ran into uniformed people. But he was betrayed a number of times -- the Germans paid for information on the whereabouts of Jews -- and he always escaped with a lot of luck.

Denunciation Was Common

Denunciation was so common in Poland that there was a special term for paid informants "Szmalcowniki" (previously a term for a fence). In many cases, the denouncers knew their victims. And while the French, Dutch or Belgians could submit to the illusion that the Jews deported to the east from Paris, Rotterdam or Brussels would be all right in the end, the people in Eastern Europe learned through the grapevine what lay in store for the Jews in Auschwitz or Treblinka.

For sure, many counter-examples can easily be found. A senior officer in Einsatzgruppe C, responsible for the murder of more than 100,000 people, complained that the Ukrainians lacked "pronounced anti-Semitism based on racial or ideological reasons." The officer wrote that "there is a lack of leadership and of spiritual impetus for the pursuit of Jews."

Historian Feliks Tych estimates that some 125,000 Poles rescued Jews without being paid for their services. It's clear that the perpetrators always made up a small minority of their respective population. But the Germans relied on that minority. The SS, police and the army lacked the manpower to search the vast areas where the Nazi leadership planned to kill all people of Jewish origin. Across the 4,000 kilometers stretching from Brittany in western France to the Caucasus, the Nazis were bent on hunting down their victims, deporting them to extermination camps or to local murder sites, preventing escapes, digging mass graves and then carrying out their bloody handiwork.

Of course only Hitler and his entourage or the army could have stopped the Holocaust. But this doesn't invalidate the argument that without the foreign helpers, countless thousands or even millions of the approximately six million murdered Jews would have survived.

In the killing fields of Eastern Europe, there were up to 10 local helpers for every German policeman. The ratio is similar in the extermination camps. Not in Auschwitz, which was run almost entirely by Germans, but in Belzec (600,000 killed), Treblinka (900,000 deaths) or in Demjanjuk's Sobibor. There, a handful of SS members were assisted by some 120 Travniki men.

Without them, the Germans would never have managed to kill 250,000 Jews in Sobibor, says former prisoner Blatt. It was the Travniki who guarded the camp, drove all the Jews from the railway wagons and trucks after their arrival in the camp, and who beat them into the gas chambers.

Was the Holocaust a European Project?

Such a stupefying number of victims raises disturbing questions, and Berlin historian Götz Aly already started asking them a few years ago: was the so-called Final Solution in fact a "European project that cannot be explained solely by the special circumstances of German history"?

Many Foreign Perpetrators Acted Voluntarily

There is no final verdict yet on the European dimension of the Holocaust. The French and Italians started late -- when most of the perpetrators were already dead -- to deal comprehensively with this part of their history. Others, such as the Ukrainians and Lithuanians, are still dragging their feet; or they have only just begun, like Romania, Hungary and Poland.

Since 1945 the countries invaded and ravaged by Hitler's armies have seen themselves as victims -- which they doubtless were, with their vast numbers of dead. That makes it all the more painful to concede that many compatriots aided the German perpetrators.

In Latvia, local assistance was greater than anywhere else. According to the American historian Raul Hilberg, the Latvians had the highest proportion of Nazi helpers. The Danes are at the other end of the scale. When the deportation of Denmark's Jews was about to begin in 1943, large parts of the population helped Jews to escape to Sweden or hid them. Some 98 percent of Denmark's 7,500 Jews survived World War II. By contrast, only nine percent of the Dutch Jews survived.

Does the Holocaust represent the low point not only of German history, but of European history as well, as historian Aly argues?

There is evidence challenging the widely-held notion that foreign perpetrators were forced to help the Germans commit murder. It's true that local helpers risked their lives by refusing to assist the German occupiers. That applied to the police units and civil servants in occupied Western Europe as much as it did to newly-formed auxiliary police in the east. But it's also true that in many places people volunteered to serve the Germans or participated in crimes without being forced to.

The Holocaust in numbers.

DER SPIEGEL

The Holocaust in numbers.

There is also the often-repeated claim that the governments of countries allied with Hitler had no choice but to hand over Jewish citizens to the Germans. That's not true either. The Balkan countries in particular quickly understood how important the "solution to the Jewish Question" was to Hitler and his diplomats -- and they tried to extract the highest possible price for their complicity.

There's also reason to doubt the assumption that the helpers were pathological sadists. If that were true, they should be easy to identify, for example within the group of 50 Lithuanians who served under the command of SS Obersturmbannfü hrer (Lieutenant Colonel) Joachim Hamann. The men would drive around the villages up to five times a week to murder Jews, and ended up killing 60,000 people. It only took a few crates of Vodka to get them in the mood. In the evenings the troop would return to Kaunas and boast of their crimes in the mess hall.

None of the Lithuanians had been criminals before. They were "totally and utterly normal," believes historian Knut Stang. Almost everywhere after the war, the murderers returned to their ordinary lives as if nothing had happened. Demjanjuk too was a law-abiding citizen. In Cleveland, Ohio, where he lived, he was regarded as good colleague and a friendly neighbor.

It's the same as with the German perpetrators. There's no identifiable type of killer -- that's a particularly disturbing conclusion reached by historians. The murderers included Catholics and Protestants, hot-blooded southern Europeans and cool Balts, obsessive right-wing extremists or unfeeling bureaucrats, refined academics or violent rednecks.

Among them was Viktor Arajs (1910-1988), a learned lawyer from a Latvian farming family who commanded a unit of more than 1,000 men that murdered its way around Eastern Europe on behalf of the Nazis. Or the Romanian Generaru, son of a general and commander of the ghetto in Bersad in Ukraine, who had one of his victims tied to a motorbike and dragged to death.

Anti-Semitism Was Rife Across Europe

And anti-Semitism? In the 1930s, anti-Semitism grew across Europe because the upheaval after World War I and the global economic crisis had unsettled people. In Eastern Europe, the tendency to regard Jews as scapegoats and to try and exclude them from the job market was especially strong. In Hungary, Jews were banned from public office at the end of the 1930s and were forbidden to work in a large number of professions. Romania voluntarily adopted Nazi Germany's racist and anti-Semitic Nuremberg Laws. In Poland, many universities restricted access for Jewish students.

The extent of the hatred of Jews is also reflected in the fact that after the end of the war in 1945, mobs in Poland killed at least 600, and possibly even thousands of Holocaust survivors. However, excessive nationalism appears to have been the more important factor, at least in Eastern Europe. Many there dreamed of a nation state devoid of minorities. In this sense, the Jews were simply one of several groups that people wanted to rid themselves of. As World War II raged, the Croats didn't just murder Jews but also killed a far larger number of Serbs. Poles and Lithuanians killed each other. Romania liquidated Roma and Ukrainians.

It's hard to determine what motivated people to kill. Often nationalism or anti-Semitism were just excuses. During the war, no one had to go hungry in Germany, but living conditions in Eastern Europe were squalid. "For the Germans, 300 Jews meant 300 enemies of humanity. For the Lithuanians they meant 300 pairs of trousers and 300 pairs of boots," says one eyewitness. That was greed on a personal level. But it also featured on a collective level. In France, 96 percent of aryanized companies remained in French hands. The Hungarian government used the assets seized from Jews to extend its pension system and reduce inflation.

Jews Were Scapegoats for Soviet Crimes

Imaginary revenge also played a part. Pogroms in Poland by local people against Jews in 1941 were based on the assumption that the Jews formed some sort of base for Soviet rule, because communists of Jewish descent had for a time been over-represented in some areas of the Soviet bureaucracy. As a result, many people blamed Jews for the crimes committed during the Soviet occupation of eastern Poland between 1939 and 1941. Stalin's secret police the NKWD had actual and presumed opponents of the regime in the Baltic States, eastern Poland and Ukraine shot or deported to Gulags. As the German troops advanced, the Soviets left behind a deeply traumatized society between the Baltic and the Carpathians -- and many fresh mass graves.

Hitler hadn't worked out all the details of the Holocaust from the start, instead assuming he would be able to drive out all Jews from his sphere of influence after a quick victory over the Soviet Union. But the German advance into the Soviet Union started faltering in autumn 1941, which raised the problem of what to do with the people crammed into ghettos, especially in Poland. Many Gauleiter, SS officers and top administrators called for their territory to be made "judenfrei" ("free of Jews" -- which meant liquidating them. The construction of extermination camps began, first in Belzec, then Sobibor, then Treblinka.

Brief Holocaust Training Course

It was a gigantic killing program in which most of Poland's Jews, 1.75 million, were murdered. The SS preferred to recruit its helpers among Ukrainians or ethnic Germans in prisoner-of- war camps where Red Army soldiers like Demjanjuk faced the choice of killing for the Germans or starving to death. Later, increasing numbers of volunteers from western Ukraine and Galicia joined the unit. The men had to sign a declaration that they had never belonged to a communist group and had no Jewish ancestry. Then they were taken to Travniki in the district of Lublin in south-eastern Poland where they were trained for their deadly profession on the site of a former sugar factory. In mid-1943 some 3,700 men were stationed in Travniki. Training for the Holocaust took several weeks. The SS men showed the new recruits how to carry out raids and how to guard prisoners, often using live subjects. Then the unit would drive to a nearby town and beat Jewish residents out of their homes. Executions were carried out in a nearby forest, probably to make sure that the recruits were loyal.

At first the Travniki were used to guard property and to prevent supply depots from being plundered. Then their German masters sent them to clear ghettos in Lviv and Lublin, where they were remorseless in rounding up their Jewish victims. Finally they were put to work in eight-hour shifts in the extermination camp. "Everyone jumped in where he was needed," recalled one SS officer. Everything worked "like clockwork."

Historians estimate that a third of the Travniki absconded despite the punishment that entailed if they were caught. Some were executed for disobedience. And the others? Why didn't they try to get out of the killing machine? Why didn't Demjanjuk? Die he allow himself to be corrupted by the feeling of "having attained total power over others," as historian Pohl argues. Was it the prospect of loot? In Belzec and Sobibor the Travniki engaged in brisk bartering with the inhabitants of surrounding villages and paid with items they had seized from the prisoners.

Perhaps there was something else, something even more disturbing that many people have deep in their psyche: following orders from authorities even if they ran counter to their conscience. Total and utter obedience.

Germany Relied on Outside Help in the Monstrous Murder Project

Germany's troops didn't have the whole of continental Europe under the gun to the same extent. Outside the Third Reich and the occupied territories the Germans needed the help of foreign governments in their monstrous murder project -- in the west as well as the south and southeast of Europe. Their support was strongest among the Slovaks and Croats whom Hitler had given their own states. The Croatian Ustasha fascists set up their own concentration camps where Jews were killed "through typhoid, hunger, shooting, torture, drowning, stabbing and hammer blows to the head," says historian Hilberg. The majority of Croatian Jews were killed by Croats.

Anti-Semitism wasn't so deep-rooted in Italy and was ordered by the state out of consideration for the Germans. An Italian military commander in Mostar (in today's Bosnia) refused to chase Jews from their homes because he said such operations "weren't in keeping with the honor of the Italian army." That wasn't the only the only such case. But it's clear that Benito Mussolini's puppet government of 1943 eagerly took part in persecuting Jews. More than 9,000 Italian Jews were deported to their deaths.

Some 29,000 Jews from Belgium were murdered, many after being denounced in return for cash. Denunciations also happened in the Netherlands and France. Local authorities obediently paved the way for the deportation of Jews and later said they hadn't suspected what fate the Jews faced. That excuse was used by henchmen, opportunists and pen-pushing bureaucrats -- a category of perpetrator that was denied for a long time after the war in France as the country sought to build a myth that the entire French people had been involved in the heroic resistance.

France was divided into two parts. Hitler's troops had occupied three fifths of the country but the southern part of the country remained unoccupied until November 1942 and was ruled by a right-wing government based in Vichy that collaborated with the Germans.

How Many Were Betrayed?

The first major roundup of Jews took place in mid-July 1942 in occupied Paris when almost 13,000 Jews who had no French passport where taken from their homes by French policemen. At least two thirds of the Jews deported from France were foreigners. The remaining third consisted of naturalized French citizens and children born in France to stateless Jews. Police "repeatedly expressed the desire" that the children should be deported as well, one SS officer noted in July 1942. Almost all deportations ended in Auschwitz.

In total almost 76,000 Jews were deported from France and only 3 percent of them survived the Holocaust. It's unknown how many of them were betrayed by the local population. In the Netherlands there's a figure that gives an indication of the extent of denunciation. The country had an authority that hunted Jews on behalf of the Nazis and that listed the property of Jews who had gone into hiding or already been deported. The "Household goods registry office" paid 7.50 guilders for every Jew who could be located -- that's about €40 in today's money. Dutch journalist Ad van Liempt has analyzed historical records and estimated that between March and June 1943 alone, more than 6,800 Jews were tracked down in this way, and that at least 54 people had taken part in this hunt once or even several times. "Most of them made this their main occupation for months," he says.

The head of the unit was a car mechanic called Wim Henneicke who evidently had good connections in the Amsterdam underworld. He built up an extensive network of informants who told him where Jews were hiding. Some 100,000 Jews from the Netherlands were murdered in concentration camps, a far greater proportion than in Belgium or France.

However, in contrast with France, Dutch collaborators were quickly punished after the war. Some 16,000 were put on trial by 1951, and most of them were convicted.

Demjanjuk is a different category of perpetrator. He's not a collaborator or head-hunter, not a policeman of the sort that contributed to the Holocaust far away from the actual killing. He was at the scene, prosecutors say in their detailed arrest warrant.

The Terrible World of the Holocaust Helpers

In the coming days doctors will decide will decide whether and for how long Hitler's last henchman from Sobibor can be put on trial. The German government wants him to face trial. "We owe that to the victims of the Holocaust," says Vice Chancellor Frank-Walter Steinmeier.

Those who suffered in the camps under Travniki men like Demjanjuk don't feel any desire for revenge when they talk about him today. American psychoanalyst Jack Terry, who was imprisoned in Flossenbürg concentration camp while Demjanjuk was a guard there, says it would suffice if Demjanjuk "had to sit in his cell for even just one day."

And Sobibor survivor Thomas Blatt says he "doesn't care if he has to go to prison, the trial is important to me. I want the truth."

Demjanjuk could provide information about Sobibor -- and about the terrible world of the Holocaust helpers.

Reporting by Georg Bönisch, Jan Friedmann, Cordula Meyer, Michael Sontheimer, Klaus Wiegrefe---------------------------------------------------------------------------

Poles Raise Germany's Nazi Past as Economic Crisis Spreads East

By Katya Andrusz

May 20 (Bloomberg) -- Germany is trying to rewrite the history of its ties with Poland, which it occupied during World War II, Polish opposition leader Jaroslaw Kaczynski said, straining ties between the two countries as Germany's economic slowdown spills over into its eastern neighbor.

"The Germans are trying to deny their guilt for the Holocaust," Kaczynski said today. "If things go on like this, Poland will be asked to pay compensation for German soldiers who died during the Warsaw Uprising," he added, referring to resistance against the Nazis in the Polish capital in 1944.

Kaczynski was commenting after the German periodical Der Spiegel said this week that Hitler's Holocaust could never have taken place without the support of local populations in occupied Europe. So many Poles denounced Jews to the Nazis that a special name was invented to describe them, the article said. Kaczynski's Law & Justice party appealed today to Foreign Minister Radoslaw Sikorski to "intervene" on the article.

Germany's economy is undergoing its deepest recession since the war, hurting imports from its trading partners as investment stalls and companies cut jobs.

Relations between Poland and its western neighbor remained troubled even after Poland's accession to the European Union following the defeat of communism in 1989. Successive Polish governments have voiced suspicion of a German-Russian gas pipeline project intended to connect the two countries via the Baltic Sea and also blame Germany for not supporting bids by Ukraine and Georgia to join NATO soon.

Maciej Giertych, a Polish member of the European Parliament, was also cited yesterday by the daily Dziennik as saying in a pamphlet that Germany is using the EU to increase its power over other nations.

The Nazis called for the creation of a united Europe that foresaw "German domination in foreign, military, monetary and economic policy," Giertych said in the paper, entitled `Quo Vadis Europa?' published on his Web site. Germany has a greater influence on European Central Bank policy than other EU member state because its headquarters are in Frankfurt, he added.

************ ********* ********* ********* *********

Polish farmers collaborated with Nazis, says Der Speigel

thenews.pl

20.05.2009

This week's edition of Der Spiegel accuses Poles and other nations of having collaborated with Nazis during World War II.

Article about collaboration with Nazis, Der Spiegel

The accomplices: Hitler's European helpers in the Holocaust reads the headline of the front-page article, accompanied by a photo of Hitler.

The article names Polish farmers, among others, as accomplices of the Nazis during World War II.

The article tells the story of John Demjanjuk, the Ukrainian SS-officer, who was recently extradited from the US to Munich to stand trial for war crimes, including the death of at least 29,000 Jews at the Sobibor Nazi death camp in southeast Poland during WW II.

Demjanjuk served as a guard at the Treblinka, Sobibor and Majdanek death camps and was known as "Ivan the Terrible" by the prisoners because of his extraordinary violence.

Der Spiegel cites the case of Demjanjuk to prove that it was not only Germans who were responsible for mass murder during the Holocaust. If it had not been for Ukrainian gendarmes, Latvian auxiliary policeman, Romanian soldiers, Hungarian railway workers, Polish farmers, Dutch land register officials, French mayors, Norwegian ministers and Italian soldiers, the Nazis would not have been able to mastermind the Holocaust, claims the weekly.

Historian Dieter Pohl, quoted by Der Spiegel, estimates that more than 200,000 non-Germans were involved in war crimes, which almost equals the number of Germans and Austrians responsible for the Holocaust.

The weekly gives reasons why it thinks non-Germans collaborated with the Nazis, mentioning fear, perversion, anti-Semitism, and a willingness to help the presumed victors of the war.

Der Spiegel claims that while Italians and the French are aware of the scale of collaboration with the Nazis in their countries, Poles fail to admit it. According to the weekly, this is surprising, considering the fact that in Poland hatred for Jews is "deep rooted" and pogroms took place in Poland even after WW II was over.

Most countries, especially from Central and Eastern Europe, have to take the responsibility for the Holocaust instead of throwing the blame entirely on Germans, claims Der Spiegel.

Spiegel divides Polish politicians

"There is freedom of press in Germany, as there is in Poland," said Poland's Foreign Minister Radoslaw Sikorski, commenting on the article by Der Spiegel, accusing Poles of collaboration with the Nazis.

Unlike Sikorski, however, the head of the Law and Justice party (PiS) Jaroslaw Kaczynski, is outraged at Der Spiegel's claims. "Germans are trying to free themselves from taking responsibility for the major crimes of Holocaust," said Kaczynski and added that, to his horror, some circles in Poland support the opinion.

"If we allow Germans go in for this sort of practice, in the future we will have to pay damages to German soldiers who died during the Warsaw Uprising," said the head of PiS.

|

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Jun 8, 2009 20:44:00 GMT 1

Personal Journey: From the Krakow ghetto, life goes on

By Ellen Tilman

The Philadelphia Inquirer

6/7/09

A memorial of the Krakow ghetto that the Nazis established. Large and small chairs are a stark reminder of emptiness.

A visit to a former pharmacy in Krakow, Poland, became a poignant moment of a trip with my husband to Eastern Europe.

I was accompanying him on a concert tour with the men's choir from Beth Sholom in Elkins Park, and visiting the Krakow ghetto, which the Nazis established in March 1941 in a city where the Jewish community dates from the 15th century.

The only non-Jewish resident there had been a pharmacist, Tadeusz Pankiewicz. Jews would come to the Eagle Pharmacy for medications and messages; some evidence suggests that the pharmacy was part of the Polish underground. In 1993, the building was turned into a National Memorial Museum and now contains pictures of the roundup and deportation of Krakow's Jews.

Outside is Plac Zgody, now called the Ghetto Heroes Square, and known as Umschlagplatz by the Nazis. It was where the Jews assembled before being transported to death camps. The Podgorze Ghetto, as it was known, was liquidated on March 13, 1943. The Jews able to work were sent to the Plaszow forced-labor camp (featured in the film Schindler's List), and the rest were transported to Auschwitz-Birkenau.

In 2005, a memorial was constructed at this site. It consists of 33 oversized and very large empty chairs and 37 smaller chairs. This stark permanent reminder of emptiness recalls the people who were never to return.

One letter in the pharmacy captured my attention. Dated May 1993, it was sent from New South Wales, Australia. It read:

"Enclosed please find a modest cheque for $250. Please accept it in the spirit in which it has been sent to you and consider it as a symbolic payment for the 3 pills of Panflavin, which you gave me in 1943 and for which I could not pay you then. I consider it a great honour to have had the privilege of sharing your warm hand. In fact, I have never forgotten your kindness for all those years. . . . "

It was signed Martin Baral.

Upon arriving home, I decided to learn more about the letter's author. I Googled his name and found a Web site of Baral family pictures. I discovered that Martin was a child while in the ghetto. He and his family escaped and spent the rest of the war hiding in Budapest. They moved to Israel and eventually settled in Australia. I sent an e-mail to the Webmaster asking if this Martin Baral was the same person whose letter was in the Eagle Pharmacy.

I quickly received a reply from Martin Baral's son. He said Martin did not return to Krakow for 50 years. Once there, he immediately looked up the pharmacist who had saved his life. He found Tadeusz destitute and in ill health. He emptied his pockets to help this noble man. Unfortunately, Tadeusz died later that year.

My emotional journey to Eastern Europe was not over until I returned home and was able to learn the fate of Martin Baral. Sometimes one must become an armchair traveler in order to complete an overseas journey.-----------------------------------------------------------

Poland and Ukraine resist restitution of heirless Holocaust property

By Cnaan Liphshiz

Ha'aretz

6/3/09

Just three weeks before an international conference on Holocaust assets, Jewish and Eastern European delegates are still debating whether countries like Poland and Ukraine should give back heirless property that belonged to murdered Jews.

While those countries have opposed restitution of property whose owners left behind no heirs, Jewish representatives of the Holocaust Era Assets Conference, scheduled to open in Prague on June 26, say such property should go to Jewish organizations in lieu of heirs.

"Until now, certain countries have resisted restitution for lost heirless property, citing laws that state that such property should go to their treasuries," said David Peleg, the newly appointed director of the World Jewish Organization for Property Return. "We don't agree with this assertion."

Advertisement

Peleg estimates the value of heirless Jewish property in Poland alone at billions of dollars.

"The reason there's so much unclaimed property is because the Nazis killed off whole families," he said.

The conference, which will bring together representatives of some 50 countries and 30 non-governmental organizations, is the first wide-scale forum involving assets from several countries to convene in over a decade, since the Washington Conference of 1998. Israeli officials say the conference may be the last opportunity to set principles that could lead to wide-scale compensation for lost Jewish property.

Asked whether he thought the recalcitrant Eastern European countries would eventually come around, Peleg would only say that "this is achievable." He said the U.S. State Department's involvement in the issue "has been very helpful."

Former Mossad official Reuven Merhav, who will head Israel's delegation to Prague, called the negotiations "intensive" and "delicate."

|

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Jun 16, 2009 19:18:11 GMT 1

The article concerns Lithuania

In Other Words: Baltic Ghosts, Lithuania is investigating Jewish Holocaust survivors as war criminals

Pakistan Daily

14 June 2009

Lithuania is investigating Jewish Holocaust survivors as war criminals—and using their own memoirs as evidence against them.

Yitzhak Arad escaped to the forest at the age of 16, days before the Jews in his native Lithuanian village were massacred. He is proud he joined the Soviet partisans to fight the Nazis and their collaborators. For a Jew, just to survive the Holocaust was a victory, he says; to tell about it was an obligation. That's why Arad wrote his memoir, The Partisan: From the Valley of Death to Mt. Zion, published in English in 1979.

The book is a raw account of an orphaned teenager fighting the Nazis in desperate conditions after the murder of 40 members of his family. Arad describes his main activities with the Soviet partisans as blowing up German military trains, and he also details some of the grislier aspects of forest warfare. In one passage, he describes a "punitive action" against the village of Girdan, where two partisans had been killed: "We broke into the village from two directions, and the defenders fled after putting up feeble resistance. We took the residents out of several houses in the section of the village where our two comrades fell and burned down the houses. Never again were partisans fired on from their village."

"It was a cruel war," the 82-year-old Arad recalled recently. "We did the best we could to survive." He dedicated his memoir to those who fought with him and died along the way—his "heroic friends."

But when Lithuania's chief war crimes prosecutor, Rimvydas Valentukevicius, read Arad's book, nearly 30 years after its publication, he didn't see a hero. He saw a possible war criminal. And in September 2007, when the prosecutor's office publicly announced an investigation into Arad, it was clear The Partisan would be Exhibit A against him. More war crimes investigations of Lithuanian Holocaust survivors have followed, and in each case, memoirs are playing a central role.

These events are all the more shocking to those who remember that the country was once a sort of Jewish promised land. Lithuania's capital, Vilnius, was known as "the Jerusalem of the North." About one third of its population in the 1920s and 30s was Jewish. Yiddish was in the air then. Synagogues welcomed the faithful. Cafes overflowed with young Jewish painters, writers, and poets. Vilna, as the city is called in Yiddish, was the seat of intellectual, spiritual, and artistic life for Eastern European Jewry.

All of that is long gone, destroyed by the Nazi war machine with the active assistance, in a dark chapter for Lithuania, of many local collaborators. Vilnius today has only one synagogue. Lithuania's once flourishing community of more than 200,000 Jews—over 90 percent of whom were annihilated during the war—is now about 4,000. All that is left are the Holocaust survivors' stories, and now those, in the case of Arad and several others, are being used against them.

How a country that was once a center of Jewish life has now begun targeting the few remaining victims of history's worst crime is a story of foreign occupiers, former Jewish partisans, and modern-day Lithuanian ethnic nationalists. But more broadly, it is a story of books, memory, and a small country's ongoing struggle to make sense of its tangled, bloody historical narratives—a struggle facing all of Eastern Europe.

In a strange twist, this whole affair began with a good-faith effort to heal those deep, lingering ethnic divisions. In 1998, President Valdas Adamkus created a high-level commission to try to establish the "historical truth" about Lithuania's horrific occupations during the 20th century: first by the Soviets from 1940-41, then by the Nazis from 1941-44, followed again by the Soviets from 1944-90. The commission attracted a prestigious collection of international scholars, including Arad, who had gone on to become a brigadier general in the Israel Defense Forces and director of Yad Vashem, Israel's Holocaust remembrance center. However, as the commission began excavating the layered narratives of guilt and suffering from this period, ethnic tensions flared.

The biggest obstacle for Lithuanians in confronting their history is the now well-established fact that hundreds, if not thousands, of Lithuanians voluntarily participated in the Holocaust. Many of the country's Jews were shot by local police and by a special unit of Lithuanian killers incorporated into the Nazi SS. Since its independence in 1990, only three Lithuanian collaborators have been charged with war crimes, and none was punished.

"The genocide of the Jews is the bloodiest page in the country's history," said Saulius Suziedelis, a Lithuanian historian and member of the presidential commission. But for many Lithuanians, he said, "just to mention that obvious fact turns them off because they want to talk about their own victimization. "

That victimization came during the brutal Soviet occupation. It was marked by the repression of Lithuanian culture, the deportation of many thousands of Lithuanians to Siberia, and the murder of Lithuanian independence fighters. The Soviets strictly controlled information and wrote Lithuania's history books. Today, as the country struggles to write its own narrative, most Lithuanians see the Soviets as the real villains of World War II. "The Spielberg view of the war is totally irrelevant to [Lithuanians] because that was not their experience," Suziedelis said. Instead, Lithuanian Jews, who allied with the Soviets to fight the Nazis, are today often regarded as deserving of punishment for Soviet crimes.

This is certainly the view of many Lithuanian "ethno-nationalists ," according to Antony Polonsky, professor of Holocaust studies at Brandeis University. In 2006, after the presidential commission published interim findings for a report that Polonsky called "a devastating account of the Lithuanian involvement in the mass murder of the Jews," these firebrands mobilized, he said. They took to the pink-tinted pages of the right-wing Respublika newspaper—Lithuania' s second-leading daily, which has been sanctioned for running anti-Semitic material. Their target was Yitzhak Arad. In an April 2006 article, Respublika published portions of his memoir and denounced him as a murderer and war criminal. The following month, Lithuanian prosecutors opened their investigation into Arad.

Some might dismiss this timing as coincidence. But not Rytas Narvydas, head of special investigations for the Genocide and Resistance Research Centre of Lithuania, which investigates and memorializes past state crimes. He and the lead prosecutor, Valentukevicius, acknowledge that the Arad investigation started in response to the Respublika article. When asked whether anti-Semitic elements in Lithuania had manipulated the war crimes prosecutor's office, Narvydas conceded, "It does happen from time to time."

Lithuanian Foreign Affairs Secretary Oskaras Jusys criticized the prosecutor for getting pushed around by "outside" elements and said the investigations never should have been opened. "The mistake was made by the prosecutor's office from the very beginning," he said. "Their mistake was to go ahead without clear evidence."

The Arad case "created so much damage" for Lithuania, Jusys said, referring to the significant diplomatic pressure imposed by the United States, the European Union, Israel, and international Jewish groups. Lithuania's foreign minister and president appealed personally to the prosecutor to drop the Arad investigation, Jusys said, and in September of last year the case was closed. But in the meantime, prosecutors had opened investigations into several other Holocaust survivors. "We have been able to clean one mess," Jusys said in frustration, "and now other things are happening again."

The most public of the ongoing investigations involves Rachel Margolis, an 87-year-old former biology professor living in Israel who joined the Soviet partisans after escaping the Vilnius ghetto. Here, too, a book is at the heart of the case. In Margolis's memoir, published in 2005 in Polish (and later in Russian and German), she recounts a partisan raid on the village of Kaniukai on January 29, 1944. Facts about the raid are heavily disputed, including whether the villagers were acting in concert with the Nazis, but the war crimes prosecutor alleges that 46 people were murdered, 22 of them children.

According to Margolis's memoir, she did not take part in the Kaniukai raid, but her longtime friend and fellow partisan, Fania Brancovskaja, did. Now an 87-year-old librarian at the Vilnius Yiddish Institute, Brancovskaja was attacked in print last year by the ultraright-wing nationalist newspaper Lietuvos Aidas. It labeled her a murderer, called on investigators to charge her with war crimes, and demanded they summon Margolis as a witness. And, last May, Lithuanian prosecutors publicly announced they were seeking to question the two women.

The heightened scrutiny of these investigations clearly frustrates Valentukevicius, the prosecutor, as does having to defend himself against accusations of anti-Semitism. When asked about it recently, he raised a copy of Lithuania's procedural code and said he's just doing his job—investigating all war crimes allegations as the law requires. But with dozens of potential cases of Lithuanian collaboration yet to be examined, the decision to focus on Jewish Soviet partisans has attracted suspicion.

So has the very public nature of the prosecutor's investigation. Faina Kukliansky, Brancovskaja' s attorney and an ex-prosecutor, complained that the former partisans are being tried by "innuendo" in the court of public opinion because prosecutors lack any evidence to try them in a court of law. "Everything has been done with a wink and a nod," she said.

Many critics agree and say it is no coincidence that nationalists sought out Margolis's memoir, a light seller at best. Prior to its publication, Margolis had detailed aspects of Lithuania's history that many would rather ignore. She helped publish works on the Holocaust, including the diary of Kazimierz Sakowicz, a searing account of the heavy participation of Lithuanians in the murder of 50,000 to 60,000 Jews in the Ponary forest outside Vilnius. The 2005 English edition of the book, for which Margolis wrote the foreword, was edited by Yitzhak Arad.

Margolis has not returned to Lithuania since prosecutors came looking for her. Brancovskaja met with prosecutors last May to explain that she was recovering from an operation at the time of the Kaniukai raid and had not taken part in it. Margolis sent her old friend a letter backing up Brancovskaja' s account, and said her memoir should be regarded as literature, not historical fact. That may be true of all memoirs, but the distinction takes on a special significance in the context of the Holocaust, where survivors write to bear witness and deniers have long seized on small inconsistencies to discount the larger event.

For his part, Arad stands by the accuracy of his account as vehemently as he denies committing any war crimes. "I am proud of what I did during the wartime," he said. "If I would feel I did something not to do, I wouldn't write a memoir."

As during the Arad affair, the world is watching Lithuania's investigations of the elderly Jews who fought with the Soviet partisans, and Brancovskaja and the others will likely escape war crimes charges. But charges may never have been the point. The prosecutor's simple act of initiating the Arad investigation was enough to derail the half of the presidential commission researching Nazi crimes and Lithuanian complicity in them. It has not published anything since 2006. This may be the investigations' most enduring harm.

"You have to do what's right, not what's easy," said David Crane, a law professor at Syracuse University and founding chief prosecutor for the U.N. war crimes court in Sierra Leone. "Some people in society may not want these things found, and in the short term, that may seem like a solution. But in the long term, 25 years from now, they'll still be arguing about this."

Other consequences are more personal. The relationship between Brancovskaja and Margolis, a friendship that started before the war, has suffered. The two women have been divided by a 65-year-old memory and a passage in a book. "It is very painful what they are doing," Brancovskaja said, sitting in the Yiddish library surrounded by the many volumes she tends. But then she added, "I have lived through so much. This is not the worst."

|

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Jun 16, 2009 21:48:50 GMT 1

Poland's Jewish heritage is about more than just deathBy Ruth Ellen Gruber

June 1, 2009

BIELSKO-BIALA, Poland (JTA) -- Outside the elegant theater in the city of Bielsko Biala in southern Poland, a billboard advertises an upcoming play. Stark letters spell out the title: "Zyd" -- Jew.

The lettering looks almost menacing, like scrawled graffiti, and I am a little taken aback.

But then I remember where I am.

This is Poland.

And the play, in fact, is an award-winning exploration of anti-Semitism and the power of stereotypes -- part of the endless continuing discussion here about the Jewish past, the Jewish present, and the long, complex and troubled relationship between Jews and Catholic Poles.

"There is no theme that Poles are more likely to discuss than Jews," the play's author, Artur Palyga told the Polish media. "It can be said that Judaism is our national passion."

"Zyd" deals with teachers in a provincial Polish town preparing for the visit of a former student, a Holocaust survivor who had attended their school before the Shoah, when Jews made up more than half the town's population.

Its portrayal of grassroots prejudice is graphic and sometimes grotesque. Indeed, the play came under fire in the right-wing press, and its premiere last year sparked protests.

Still, it won the main prize at a national festival of contemporary Polish drama for being "an honest, brave and theatrically precise attempt to settle accounts with the difficult Polish past."

The play is essentially about memory. In particular, it's about the various uses to which memory is put, and how memory differs in the minds of different people considering the same past.

These issues have suffused much of my own work over the past two decades, as I have researched Jewish heritage sites in East and Central Europe and chronicled the Jewish experience in places were few or no Jews live today.

How are Jews and Jewish heritage remembered? Which Jewish places and personalities are incorporated into the local consciousness? How do local people choose to portray an important part of the population that was savagely removed, almost overnight?

I found Bielko Biala permeated with examples of how perspective influences memory.

They ranged from indifferent disregard to the kitschy commercialization of a "Jewish-style" restaurant called Rabbi, to an earnest attempt to acknowledge the contribution of Jews to the city.

Bielsko Biala was officially established in 1951 with the amalgamation of two towns on opposite sides of the Biala River, which for centuries formed the border between the Austrian Empire and Poland, and then the regions of Silesia and Galicia.

Before 1939, the population was divided among ethnic Germans, Jews and Poles, and the city remains a stronghold of Protestantism. The Nazis absorbed it into the Reich, and almost all the Jews were killed. After World War II, Poland took it over and expelled the ethnic Germans.

Only a small Jewish community lives here today, but Jews played a major role in local history. In the 19th century, Jewish industrialists helped build the city into a major textile center, and a local Jewish architect, Karol Korn, designed key buildings that still define Bielsko Biala.

Korn's grandest building -- the Moorish-style great synagogue -- no longer exists. Erected in 1881, it dominated the city's main avenue until it was blown up by the Nazis in 1939.

Today, a contemporary art gallery occupies the spot; a small plaque on an outer wall commemorates the destroyed building but says nothing about the community it once served.

There's a puppet theatre now next door, where the Jewish culture center once stood, and a courthouse occupies the former Jewish community building across the street. Its elaborate decoration, I was told, represents the seven fruits mentioned in the Torah.

The Jewish cemetery, whose red-and-orange striped ceremonial hall is another Korn design, is well maintained and designated a cultural monument. Among the tombs is a poignant memorial to Jewish soldiers who fell fighting for the Austrians in World War I.

All these sites, and more, are noted on Jewish heritage itineraries included in local guidebooks available at the tourist information office and the city museum. On sale in both places I found reproductions of old postcards portraying the synagogue in all its glory as a major pre-war landmark.

I have no way of knowing who follows these itineraries or purchases the postcards. But, at least for tourists, they clearly acknowledge the Jewish contribution to the town and set Jewish history and heritage here within the general matrix.

This marks a welcome contrast to the "Jewish heritage package" offered by one of the city's leading hotels.

Far from exploring the rich historic contribution of Jews here, its itinerary is simply a round trip to Auschwitz, with "sightseeing" at the memorial museum there, then dinner back at the hotel's restaurant.

Bielsko Biala is only 25 miles from Auschwitz. I would certainly urge anyone visiting the town to take a day and go there. But promoting a tour of the Nazis' most notorious death camp as a Jewish heritage package banalizes Jewish heritage and the Holocaust, and both ignores and insults the memory of the generations of Jews who lived here (and often prospered).

In Bielsko Biala, Poles have begun to offer up a more nuanced take on history -- Jewish and Polish. Unfortunately, however, hotel tourist packages tend to offer only what their clients demand. Jews should take the lead in demanding more.

Even in places where few or no Jews live anymore, Jewish heritage must not be equated with its destruction. Nor, indeed, should the centuries-old Jewish experience be defined solely in terms of death.

|

|

|

|

Post by tufta on Jun 17, 2009 18:36:22 GMT 1

Poland's Jewish heritage is about more than just death

It's a great day today: at last you've noticed!  ;D ;D |

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Jun 17, 2009 18:58:15 GMT 1

Poland's Jewish heritage is about more than just death

It's a great day today: at last you've noticed!  ;D ;D I knew it from the beginning. I always (especially after you started Good POL-JEW Neighbourhood) wanted to draw your attention to the fact that the name of the thread is NEIGHBOURHOOD. That it was troubled is a fact of history, but it WAS neighbourhood with all its consequences.... See the photos from a site with English commentary: www.eilatgordinlevitan.com/krakow/krakow.html   About Jews in Krakow www.ushmm.org/wlc/article.php?lang=en&ModuleId=10005169![]() [/img] ![]() [/img] |

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Jun 20, 2009 22:14:53 GMT 1

Poland's Jews Emerge From Shadows

Tad Taube

JTA Wire Service

6/18/09

This month marks the 20th anniversary of the fall of communism in Poland and the rebirth of Jewish life. Today's Jewish revival is viable because Poland is a stable democracy for the first time in its history.

Today's society, based on law and respect for individual rights, provides an environment in which Poland's citizens can reconnect with a Jewish past that they may hardly know.

The generations born after 1989 no longer harbor fears that the practice of a Jewish religious tradition may bring danger, whether from fascism and the desperations of war or from communist repression. In fact, the emergence of energetic new Jewish institutions and cultural life and traditions promises that the New Poland will regain its visible and important position in the international Jewish community.

It is an incredible outcome following 50 years of Nazi and Soviet domination. But New Poland and the Jewish cultural revival taking place there must be understood against the backdrop of 1,000 years of vibrant Jewish civilization in Poland. This extensive period, often referred to as the "Jewish Golden Era," is the foundation of today's global Jewry:†More than 70 percent of the Jews in the United States and mo re than 60 percent of the Jews living in Israel come from families with roots in Poland.

As Poland's Chief Rabbi Michael Schudrich has noted, "Where would Israel and American Jewry be without their Polish history?"

Rabbi Schudrich's question recognizes that Jews, above all others, live their history. Their sense of peoplehood supersedes differences in practices, and their commitment to Israel helps bind them together. It is continuity with the past and the promise of the future that Jews share with one another and with the world around them. Their deep and long heritage also serves as the underpinning of Judeo-Christian Western culture. Where would Western civilization be without Judaism and Jewish history?

Indeed, the Western view embodies a Judeo-Christian perspective that Western culture owes much of its foundations to that Jewish Golden Era. The Jewish millennium in Poland began in the 11th century, when European Jews started moving eastward into Poland and its neighboring states. Across shifting political allegiances and boundaries, these Jewish pioneers held a single religious and cultural identity. The communities they built performed a critical role in the development of Eastern Europe, with Poland at its center.

In the 16th century, the culture and life of Yiddish-speaking Eastern European Jews was co-extant with the Polish empire, which at its height extended from the Baltic in the north through parts of Russia and Ukraine in the east and south into the Balkans.

The emergence of Yiddish literature, centers of rabbinic learning, and new Judaic practices during the 17th and 18th centuries reflected a richness of traditional culture in a changing, more secular world. Migration west, to northern Europe and to the Americas during the 19th and early 20th centuries, was matched by a new Jewish urbanism and an emerging Jewish middle class throughout central Europe. On the eve of World War II, one in seven Warsaw inhabitants was Jewish.

After the devastation of the Holocaust, few could imagine that again there would be functioning synagogues in eight Polish cities, Jewish day schools and academic programs with enrollments in the thousands, and community centers where Jews of all ages share companionship and deepen their understanding of Judaism.

Who could have predicted during the long years of Soviet domination and precarious Jewish life that Poland would ever become a democracy with Jewish legislators in Parliament, Jewish cabinet members and Jewish politicians active in towns across the land? Did anyone foresee that Poland and Israel would become important trading partners and strategic allies, or that Israeli visitors would be commonplace in Polish cities?

Moreover, Jewish cultural life is stronger for the will ingness of non-Jewish Poles to support their fellow citizens in the exploration and celebration of a long-shared culture. Education in democratic norms has made both Poland's government and its people increasingly intolerant of anti-Semitism. Growing tolerance and an awareness of Jewish participation and integration in civil society have opened Polish eyes to their newly rediscovered culture of Judaism.

Witness, for example, the Jewish Culture Festival held in Krakow each summer. This national and international celebration of Jewish culture attracts nearly 20,000 non-Jewish and Jewish participants from Poland, Europe, the United States and Israel.

Through support of events like this, with all their positive implications, the Taube Foundation joins with other international Jewish organizations and individuals to renew our shared commitment to strengthen the institutional life of Polish Jewry and broaden the world's understanding of Jewish peoplehood as viewed through the historical role of Polish Jews.

Tad Taube is the chairman of the Taube Foundation for Jewish Life & Culture, and honorary consul for the Republic of Poland. This summer, the foundation will celebrate a new sister-city relationship between Krakow and San Francisco. This story courtesy the JTA Wire Service, www.jta. org .--------------------------------------------------------------------------

Construction set for Polish Jewry museum

June 18, 2009

ROME (JTA) -- Construction on the long-planned Museum of the History of Polish Jews is set to begin in Warsaw.

Poland's culture minister, Warsaw's mayor and other officials signed a contract Wednesday authorizing Poland's largest construction engineering company, Polimex-Mostostal, to begin work on the multimillion- dollar project on June 30.

Polimex-Mostostal chairman Konrad Jasko said the building, a glass-walled structure designed by Finnish architect Rainer Mahlamaki, would be completed in 33 months.

The museum will be located in the heart of what was the World War II Warsaw Ghetto, facing the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising Monument that was erected there in 1948.

In a statement released Thursday, the museum said that a gala ceremony will mark the start of construction. A group of 100 American cantors on a concert tour of Poland are scheduled to perform.

Meanwhile, the future museum launched a Virtual Shtetl Web site Tuesday to help build the museum's collection, the French news agency AFP reported.

The site contains information about 800 Polish cities and towns that were home to Jewish shtetls before the Holocaust. Users can add information and eyewitness testimony to the site.---------------------------------------------------------------------------

New anti-Semitic incidents in Poland

by: Gigi Luz 17/Jun/2009

WARSAW (EJP)---A synagogue in the Polish city of Wroclaw was desecrated last weekend by unknown people who painted a swastika, the SS symbol as well as the inscription "Jude Raus" (Jews out).

The incident at The White Stork Synagogue ('Synagoga Pod Bialym Bocianem') was reported to the local police.

Similar graffiti were also found at a nearby Jewish Information Center which had already been targeted earlier this year by people who painted the words "Free Palestinien" in English on the house.

Cleaning the graffiti will cost the Wroclaw municipality about 1500 euros (2080 dollars).

On Tuesday, an anti-Semitic inscription in Polish was also found on the entrance sign of the Gdansk-Chelm Jewish cemetery. The inscription translates to "Jews to the oven, for this is your place".

The Chelm cemetery is one of the oldest Jewish cemeteries in Central Europe, dating back to 1694. It was recently renovated.------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Remembering Poland's Jewish heritage

thenews.pl

15.06.2009

A Festival of Jewish Culture is being held in the north east town of Bia³ystok.

Held under the motto Zachor (`Remember!' in Hebrew), the event is a tribute to Jewish artists whose roots are in eastern Poland. The programme includes exhibitions Israel – yesterday and today and paintings by the Danish artist Hans Oldau Krull, theatre performances, films and an open-air concert featuring ensembles from Poland (Di Gallitzyaner Klermorim) and Israel (Meleh-Maim) as well as American musicians (Yael Strom, Elizabeth Schwartz and Peter Stan).

The Festival's special guest is Sara Nomberg-Przytyk, who after the liquidation of the Jewish Ghetto in Bia³ystok was a prisoner of the Nazi German death camp of Auschwitz. She remained in the camp from January 1944 until 1945, when retreating Nazis evacuated it and was then transferred to Ravensbruck, Germany, and finally liberated by the Allied forces.

Nomberg-Przytyk is the author of two books of reminiscences: Samson's Column and Auschwitz. True Tales From a Grotesque Land (both translated into English).

In its review of the latter, the New York Times write: `Mrs. Nomberg-Przytyk' s book doesn't provide new factual information about Auschwitz, but her unusual attention to the details of human character that emerged under the cruel and extreme conditions of the death camp sets `Auschwitz'' apart from the many important and moving books written by other survivors.

|

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Jul 3, 2009 20:22:01 GMT 1

Jewish-born Polish priest dreams of Aliyah

By Donald Snyder

The Forward

6/21/09

When Romuald Jakub Weksler-Waszkinel applied to immigrate to Israel as a Jew under the Law of Return last October, Israeli authorities delayed responding to his request for months.

Perhaps it was the priest's white-band collar around his neck that had something to do with this.

Yet ultimately, Israel's Interior Ministry did issue the 66-year-old Polish cleric, scholar and professor at Catholic University of Lublin a two-year residency visa. It was, it seems, an imperfect compromise with a priest who insists: "I am Jewish. And my mother and father were Jewish. I feel Jewish."

Speaking through an interpreter during a phone interview, he said, "Going to Israel would be the return of the Jewish child who took the long way home."

Born in 1943 in Nazi-occupied Poland, Weksler-Waszkinel did not know that he was Jewish until he was 35 years old, 12 years after he was ordained as a Roman Catholic priest. Nor did he know that his birth parents, both ardent Zionists, were murdered by the Nazis after entrusting his care to a Polish Catholic family to save his life. It took him 14 years after he learned he was Jewish to find his real name and the names of his parents. "So in a way, it took me 14 years to be born," the priest said.

"My mother?s dreams went up in the flames of Sobibor," he explained, referring to the death camp in Poland where some 260,000 Jews were murdered.

Weksler-Waszkinel is not the only one who grapples with a dual identity. Mark Shraberman, chief archivist at Yad Vashem, Israel's Holocaust museum and research institute, said in an interview in Jerusalem that he receives many letters from Poles who are discovering that they are of Jewish origin. "They find out the truth when one of their parents is dying," Shraberman said. He added that he recently received a letter from another Polish priest in a small town who just found out that he is Jewish.

But Weksler-Waszkinel, in seeking to rediscover his lost identity by immigrating to Israel, is taking his search for that identity further than most. Though he sought originally to become recognized by the government as a Jew under the Law of Return ? the law that grants any Jew immediate Israeli citizenship ? he pronounced himself "very satisfied" with his two-year visa.