|

|

Post by Bonobo on Jan 21, 2018 20:21:36 GMT 1

Once, the powerful Soviet Union was based on two major countries - Russia and Ukraine. Today, Russians dream of bringing it back to life again, but without Ukraine it won`t be possible. However, most Ukrainians view Russians as invaders and occupiers. Russia won Crimea, indeed, but it lost Ukraine at the same time.  Interesting analysis from an Ukrainian site bunews.com.ua/opinion/item/how-putin-lost-ukraine-the-kremlin-hubris-that-led-russia-into-self-defeating-ukraine-hybrid-war

UKRAINIAN IDENTITY AND RUSSIAN IMPERIALISM

Russia’s imperial ambitions came undone because Vladimir Putin fatally underestimated the strength of Ukrainian national spirit

[...]

What Moscow failed to anticipate was the wave of patriotic emotion that surged across Ukraine in the wake of Russia’s hybrid assault. Thousands of Ukrainians took up arms in the spring of 2014, forming volunteer battalions that bolstered the country’s paper-thin defenses and stopped the Russian advance in its tracks. Behind them stood an army of civilian volunteers who provided improvised logistical support including everything from food and uniforms to armor and ammunition. In many of the cities targeted by Russia’s hybrid offensive, local communities mobilized to thwart the Kremlin’s plans, taking to the streets and filling the gaps created by corrupt and ineffective state institutions. This miracle of volunteerism saved Ukraine and placed the Kremlin in its current predicament.

Russia in denial

It is hardly surprising Russia failed to predict the Ukrainian backlash its attack would provoke. Ever since the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Kremlin’s Ukraine policy had been driven by a toxic and self-defeating blend of wishful thinking and colonial condescension rooted in notions of Ukraine as a component part of the historic Russia state. Over the years, Vladimir Putin has repeatedly stated his conviction that Ukrainians and Russians are “one people” fated to remain bound together. There is little to suggest he envisages this as an equal partnership. Indeed, in 2008, the Russian leader reportedly told US President George W. Bush that Ukraine was “not even a proper country”.

Such beliefs are by no means limited to the upper echelons of the Kremlin. They run deep in Russian society, where many still struggle to accept the reality of Ukrainian independence and regard Ukraine’s post-Soviet detachment from Russia as both artificial and temporary. In this context, Ukraine does not quality as a foreign country in the manner of France and Germany, or even fellow post-Soviet nations like Georgia and the Baltic states.

These assumptions of indivisibility are rooted in the deep historic ties connecting Russia and Ukraine, including a shared Orthodox faith and Slavic ethnic identity. Both nations trace their roots back to the early medieval Kyiv Rus state, and pay homage to the same princely Slavic ancestors. During the twentieth century, the lines separating Russia and Ukraine grew increasingly blurred due to relentless Russification campaigns in Soviet Ukraine and massive population transfers in both directions. As a result, millions of families now have relatives on both sides of the border.

Modern Russia and Ukraine remain culturally closer than almost any other two European nations. Until the outbreak of the current conflict, they inhabited a common pop culture universe encompassing the same set of celebrities, TV shows, movies, literature, music, and everyday points of reference. Jokes did not get lost in translation. Social media memes passed effortlessly between Russian and Ukrainian users. Ukrainian pop stars were household names in Russia, while Russian soap operas were primetime hits on Ukrainian channels.

The casual intimacy and intergenerational familiarity underpinning this relationship has made it particularly difficult for Russians to accept Ukrainian attempts to gravitate towards the Euro-Atlantic world. Perhaps inevitably, many have chosen to see this process as an inexplicable and despicable act of betrayal. Such attitudes overlook the differences that have always existed between Russia and Ukraine. Despite the cultural closeness of the two nations, Ukraine has a long history of attempts to assert a separate national identity. This struggle stretches back at least to the mid-nineteenth century, and arguably far further. It has always been part of the relationship, despite repeated and often brutal attempts by the Tsarist and Soviet authorities to suppress it. In many ways, the events of the past three years are merely the latest chapter in what is one of European history’s longest-running epics.

Diverging Post-Soviet Paths

Since the collapse of the USSR, the differences between the two countries have become more and more prominent as Ukrainian and Russian societies set out on increasingly divergent trajectories. Ukraine emerged from the chaotic 1990s eager to follow the path of European integration, while Russia sought a return to the stability of authoritarian empire. An entire generation of Ukrainians with no personal knowledge of the shared Soviet past came of age, giving voice to the country’s growing sense of self. They overwhelmingly embraced the idea of Ukraine’s European identity, while rejecting reunion with a Russian state that appeared to be moving in the opposite direction.

This growing rift with Ukraine has been genuinely distressing for many in Russia, while also proving extremely awkward for the Kremlin. Rather than acknowledging the diverging paths of the two countries, Moscow has preferred to portray manifestations of Ukrainian independence as the work a radical nationalist fringe in league with foreign agents. Famously, the Kremlin has attributed Ukraine’s two post-Soviet popular uprisings almost exclusively to this cocktail of nationalist extremism and insidious Western influence, despite the decisive role played by millions of ordinary Ukrainians in both the 2004 Orange Revolution and the 2014 Euromaidan Revolution.

These comforting fictions led Russia into the disastrous miscalculations of the Novorossia campaign. Based on its own carefully curated vision of Ukraine, there was every reason to expect a warm welcome when Kremlin agents seized control of entire regions and began calling for Russian military support. When this welcome did not materialize, Russia placed the blame on a motley crew of phantom fascists, CIA agents and other international villains. In reality, the Kremlin had simply failed to appreciate the strength of Ukrainian national spirit – especially among the country’s millions of Russian-speakers and those with no Ukrainian ethnic heritage. This failure was the direct result of decades of Ukraine denial throughout Russian society.

The resulting conflict has plunged the world into a new Cold War and caused untold suffering to millions of Ukrainians, but it has also consolidated Ukraine’s sense of national identity while reminding both local and international audiences of the differences between these two historically close nations. The Kremlin’s Novorossia project was supposed to end what many in Russia see as the aberration of Ukrainian independence. Instead, it has cemented the country’s place on the European map while earning Putin the unwelcome title of the man who lost Ukraine.PS. Good luck, Ukrainians. May your aspirations for a democratic, independent, rich state come true one day.  |

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Mar 18, 2018 12:55:07 GMT 1

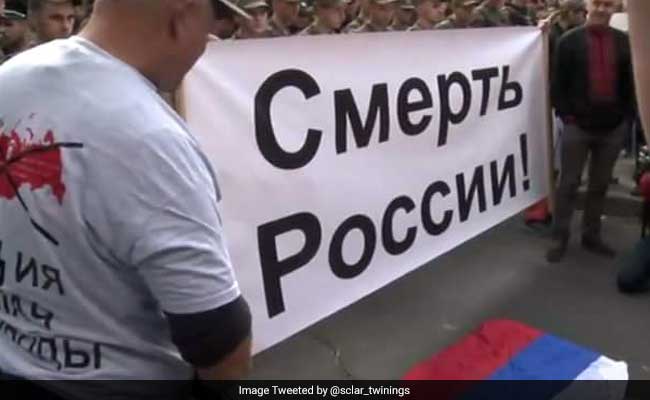

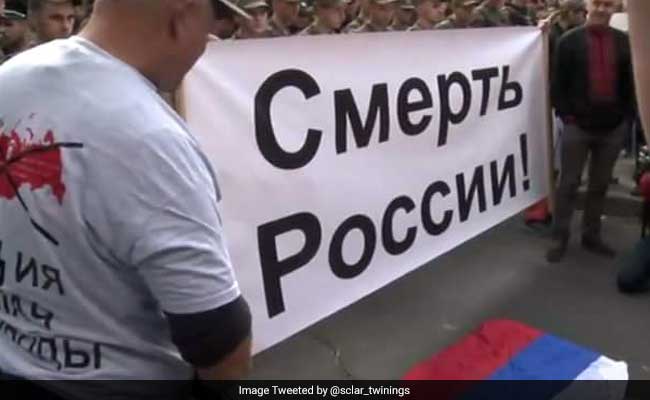

The relations have been bad since Russians took control over Crimea which had belonged to Ukraine but had been treated by Russians as their own land. Of course, today Ukrainians are not very happy because of that loss and vow to do everything to get Crimea back. To make matters worse, Eastern part of Ukraine, which has always been strongly pro-Russian, declared secession and managed to defend it with the substantial help of the Russian army. Ukrainian losses altogether  In such a suituation it is natural that tensions have been arising regularly. I don`t even talk about the warfare in Donieck area but every day minor conflicts. E.g., today

Kiev: Dozens of right-wing activists blocked the entrance to Russia's embassy in the Ukrainian capital, where a polling station has been set up for Russian citizens to vote in their country's parliamentary elections.

One demonstrator has been detained in a scuffle with police.

Comments

A leader of the nationalist Svoboda party, Igor Miroshnichenko was among the demonstrators Sunday. He said Ukraine should "not allow the enemy and state aggressor that stole Crimea to conduct illegal elections in Ukraine."

Russia annexed Crimea in 2014 following the months of unrest that drove out Ukraine's Russia-friendly president.

www.ndtv.com/world-news/protesters-block-russian-embassy-in-kiev-on-election-day-1460164Death to Russia   |

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Mar 23, 2018 22:30:59 GMT 1

Ukraine's air defense forces on alert because of Russian provocations at Crimea border 18:51, 22 March 2018

Ukraine's air defense forces have been put on alert after the Air Force of Ukraine on March 22 detected provocative actions by the air unit of the Russian Aerospace Forces along the eastern and southern airspace borders of Ukraine for the second time within a month. Russian fighter and bomber aircraft carried out flights from the airfields of Shaykovka, Krymsk and Belbek and closely approached the state border of Ukraine, the administrative border between the mainland of Ukraine and Russian-occupied Crimea, Ukraine's Air Force Command reported on Facebook on March 22.Read more on UNIAN: www.unian.info/war/10053194-ukraine-s-air-defense-forces-on-alert-because-of-russian-provocations-at-crimea-border.html

|

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on May 3, 2018 8:24:10 GMT 1

Ukrainians openly talk about the war with Russia. www.kyivpost.com/ukraine-politics/ato-ends-joint-forces-operation-launched-donbas.html

As ATO ends, Joint Forces Operation launched in Donbas

By Illia Ponomarenko.

Published April 30. Updated April 30 at 5:42 pm

The Anti-Terror Operation, conducted by Ukrainian forces against Russian-led forces in the Donbas since April 2014, is over.

But Russia’s war, which has already claimed more than 10,300 lives, is not. Starting at 2 p.m. on April 30, Ukraine launched a new campaign, the Joint Forces Operation, led by the country’s top military command.

Ukrainian President and Commander-in-Chief Petro Poroshenko signed the order to launch the new operation.

“Today, the large-scale anti-terror operation in the Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts is finished,” Poroshenko said during a meeting with the country’s top security and defense leadership in Kyiv. “Now we are starting a military operation under the guidance of the armed forces to ensure the protection of the integrity, sovereignty, and independence of our country.”

Even though Ukraine remains committed to the peaceful reintegration of the occupied Donbas, the Joint Forces commander must be ready to repel a new large-scale Russian invasion, Poroshenko said.

Besides, he added, Ukrainian troops deployed all along the front line reserved the right to retaliate to any armed provocations and attacks by Russian-led forces.

“The confrontation with the Russian aggressor will finish when the last patch of Ukrainian territory is liberated,” Poroshenko said. “This includes both Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts and occupied Crimea.” |

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Oct 9, 2018 21:09:33 GMT 1

Russians openly talk about partitioning Ukraine. For a smoother process, they suggest Poland be a partitioner, too.  Here, a scene from a Russian TV discussion. Aren`t they mad?  |

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Oct 12, 2018 23:03:45 GMT 1

Ukraine gained more independence from Russia - this time in religious sphere. www.politico.eu/article/ukrainian-orthodox-church-granted-divorce-from-moscow-ecumenical-patriarch-bartholomew/

Ukrainian Orthodox Church granted divorce from Moscow

Quest for independence has acted as a proxy for the military struggle between Russia and Ukraine.

By David M. Herszenhorn

10/12/18, 12:57 AM CET

Updated 10/12/18, 4:52 PM CET

Russia may still have its grip on Crimea and Donbas, but on Thursday the Orthodox Church ended Moscow’s 332-year control over the Ukrainian Orthodox Church.

Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew, the archbishop of Constantinople-New Rome and worldwide leader of the Orthodox Church, announced Thursday that the church had granted “autocephaly,” or independence, to the Ukrainian Church. It revoked a synodal letter in 1686 that had granted the patriarch of Moscow control, including the power to ordain the metropolitan of Kiev.

The quest for independence of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church has become a hugely contentious proxy for the ongoing military struggle between Russia and Ukraine. And the decision announced by Bartholomew threatens to create a breach between Moscow and Constantinople that some church-watchers say could cause the deepest divide since the Great Schism of 1054 that separated the Catholic and Orthodox churches. |

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Oct 19, 2018 22:58:10 GMT 1

Russia may still have its grip on Crimea and Donbas, but on Thursday the Orthodox Church ended Moscow’s 332-year control over the Ukrainian Orthodox Church. Russian leaders are utterly pissed off because the Ukrainian move means that Moscow Orthodox Church will be marginalised not only in Ukraine but also in the world. That`s funny but it really seems Russians presumed their annexation of Crimea and control over Donbas would go unnoticed by Ukrainians.   Also, they believed that their Internet games during US elections would go unnoticed in America, too.   www.digitaljournal.com/news/world/russian-fm-says-independent-ukrainian-church-is-us-backed-provocation/article/534463 www.digitaljournal.com/news/world/russian-fm-says-independent-ukrainian-church-is-us-backed-provocation/article/534463

Russian FM says independent Ukrainian Church is US-backed 'provocation'

Listen | Print

By AFP Oct 12, 2018 in World

Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov on Friday said the Istanbul-based Ecumenical Patriarchate's decision to recognise the independence of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church was a "provocation" backed by Washington.

He described the move as "provocation by Patriarch Bartholomew of Constantinople, undertaken with direct public support from Washington" during a media interview, according to a transcript of the exchange on the foreign ministry's website.

"Interfering in Church life is forbidden by law in Ukraine, in Russia and, I hope, in any normal state," he said.

The Holy Synod chaired by the Patriarch of Constantinople in Istanbul on Thursday said it had agreed to recognise the independence of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church, which has historically operated under Moscow's umbrella.

The move was met with fury by the Patriarch of Moscow, who would effectively lose influence over thousands of parishes if they decide to split off and join the new independent church.

|

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Nov 25, 2018 21:02:49 GMT 1

Russia still exerts military pressure on Ukraine.

Russia blocks Ukrainian navy from entering Sea of Azov

Andrew Osborn

MOSCOW (Reuters) - Russia stopped three Ukrainian navy vessels from entering the Sea of Azov via the Kerch Strait on Sunday by placing a huge cargo ship beneath a Russian-controlled bridge, with officials from both countries accusing the other of provocative behavior.

A bilateral treaty gives both countries the right to use the sea, which lies between them and is linked by the narrow Kerch Strait to the Black Sea. But tensions around the sea have escalated since Russia annexed Ukraine’s nearby Crimea in 2014.

Moscow is able to control access between the Sea of Azov and the Black Sea after it built a bridge that straddles the Kerch Strait between Crimea and southern Russia.

A Reuters witness said on Sunday that a bulk cargo ship had been used to block the channel beneath the bridge and that he had seen two Russian Sukhoi Su-25 warplanes flying overhead. Russian state TV said Russian combat helicopters had also been deployed to the area.

Tensions surfaced on Sunday after Russia tried to intercept the three Ukrainian ships — two small armored artillery vessels and a tug boat — in the Black Sea, accusing them of illegally entering Russian territorial waters.

The Ukrainian navy said a Russian border guard vessel had rammed the tug boat, damaging it in an incident it said showed Russia was behaving aggressively and illegally.

It said its vessels had every right to be where they were and that the ships had been en route from the Black Sea port of Odessa to Mariupol, a journey that requires them to go through the Kerch Strait.

Russia’s border guard service accused Ukraine of not informing it in advance of the journey, something Kiev denied, and said the Ukrainian ships had been maneuvering dangerously and ignoring its instructions with the aim of stirring up tensions.

It pledged to end to what it described as Ukraine’s “provocative actions”, while Russian politicians lined up to denounce Kiev, saying the incident looked like a calculated attempt by President Petro Poroshenko to increase his popularity ahead of an election next year.

Ukraine’s foreign ministry said in a statement it wanted a clear response to the incident from the international community.

Syria, Russia accuse rebels of Aleppo gas attack

“Russia’s provocative actions in the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov have crossed the line and become aggressive,” it said. “Russian ships have violated our freedom of maritime navigation and unlawfully used force against Ukrainian naval ships.”

Both countries have accused each other of harassing each other’s shipping in Sea of Azov in the past and the U.S. State Department in August said Russia’s actions looked designed to destabilize Ukraine, which has two major industrial ports there.

EDIT: Russians attacked and overpowered Ukrainian vessels in the Azov Sea.

|

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Nov 27, 2018 21:09:07 GMT 1

|

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Dec 2, 2018 17:57:26 GMT 1

Poland stands by Ukraine. Polish Foreign Minister Jacek Czaputowicz on Saturday (December 1) called for the European Union to impose new sanctions on Moscow after Russia seized three Ukrainian naval ships and took their crew. Donald Tusk: EU will extend Russia sanctions in December The European... czytaj dalej » During a two-day visit to Kiev, Czaputowicz held meetings with his counterpart Pavlo Klimkin and Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko. Czaputowicz and Klimkin took part in a commemoration ceremony for tens of thousands of victims of Josef Stalin purges in Bykivnya, a wooded area on the outskirts of Kiev. Among those executed there in 1940 by the Soviet secret police (NKVD) were about 3,500 Polish officers. Poland considers the Bykivnya killings to be a part of broader Katyn massacres - a series of mass executions of Polish nationals, many of them officers, by NKVD in spring of 1940. (http://www.tvn24.pl)www.tvn24.pl/tvn24-news-in-english,157,m/polish-mfa-wants-eu-to-impose-new-sanctions-on-russia,888760.html |

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Dec 13, 2018 22:46:46 GMT 1

Official end of Ukrainian Russian friendship. Why should fiction be prolonged any longer? www.rferl.org/a/poroshenko-signs-law-terminating-ukrainian-russian-friendship-treaty/29648193.htmlKYIV -- President Petro Poroshenko has signed into law a bill to terminate Ukraine's friendship treaty with Russia.

In a video comment posted on the presidential website, Poroshenko called the law "part of our strategy towards fully breaking with the colonial past and reorientation towards Europe."

The treaty is due to expire on March 31. On December 6, Ukrainian lawmakers voted not to prolong it beyond that date.

Signed in 1997, the treaty obliges Russia and Ukraine to "respect the territorial integrity of each other and confirm the inviolability of current mutual borders."

It also says that Ukraine and Russia should build bilateral relations "based on principles of mutual respect of sovereign equality, inviolability of borders, peaceful resolution of differences, without the use of force or the threat to use force."

Ukrainian government forces have been fighting against Russia-backed separatists in the eastern Ukraine since April 2014, shortly after Russia seized Ukraine's Crimean Peninsula and forcibly annexed it.

Although Moscow denies interfering in Ukraine's domestic affairs, the International Criminal Court (ICC) in November 2016 ruled that the fighting in eastern Ukraine is "an international armed conflict between Ukraine and the Russian Federation." |

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Dec 16, 2018 11:24:50 GMT 1

Russians are furious that Ukrainians are making their church independent of Russia. But they can`t help it, Russians are not ready for a full scale invasion of Ukraine. www.theguardian.com/world/2018/dec/15/ukrainian-priests-rile-moscow-with-moves-to-set-up-independent-orthodox-church

Ukraine riles Moscow as it announces head of new independent Orthodox church

Poroshenko calls it ‘sacred day’ as Kiev takes further step out of Russia’s orbit

Agence France-Presse in Kiev

Sat 15 Dec 2018 10.52 GMT

Last modified on Sat 15 Dec 2018 17.38 GMT

Ukraine announced the leader of a new national church on Saturday, marking an historic split from Russia which its leaders see as vital to the country’s security and independence.

The Ukrainian president, Petro Poroshenko, said Metropolitan Epifaniy, of the Kiev Patriarchate church, had been chosen as head of the new church.

“This day will go into history as a sacred day ... the day of the final independence from Russia,” Poroshenko told thousands of supporters, who shouted “glory, glory, glory”.

Relations between Ukraine and Russia collapsed following Moscow’s seizure of Crimea in 2014. Ukraine imposed martial law in November, citing the threat of a full-scale invasion after Russia captured three of its vessels in the Kerch Strait.

The Ukrainian Orthodox Church has been beholden to Moscow for hundreds of years, and Ukraine’s leaders see its independence as vital to tackling Russian meddling. |

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Dec 21, 2018 8:44:18 GMT 1

Ukrainians` point of view on Russian aggression against their country www.politico.eu/article/vladimir-putin-is-tightening-his-grip-on-ukraine-russia-sea-azov-kremlin/

Putin is tightening his grip on Ukraine

Kiev needs international help to deescalate volatile situation in Sea of Azov, writes Ukraine’s foreign minister.

By Pavlo Klimkin

12/20/18, 4:01 AM CET

Updated 12/20/18, 6:20 AM CET

KIEV — Ukraine’s Christmas markets may be in full swing, but the season isn’t feeling particularly festive this year. Our thoughts are with the 24 Ukrainian sailors who were attacked and captured by Russia last month in the Sea of Azov, and the Kremlin’s attempts to destabilize the region.

With a level of contempt and disregard for international law with which the world is sadly all too familiar, Russia has sought to present our captured servicemen as “criminals.” It blocked consular access, a direct violation of international laws, and gave us no information of their welfare for 11 days.

But no crime has taken place.

Our ships were navigating sea routes where freedom of navigation is guaranteed by international maritime law. This is not an opinion but an indisputable fact. The only “crime” to have taken place was that perpetrated by Russian forces, which fired on and then seized Ukrainian ships and their crews in open waters.

Russia’s jaw-dropping lack of respect for the rules that govern international waters is a significant and dangerous challenge to all law abiding countries.

Sadly, it is in keeping with what we’ve come to expect from Russian President Vladimir Putin.

In May last year, the Kremlin opened a 12-mile bridge over the Kerch Straits, the waterway connecting occupied Crimea with the Russian mainland. Putin is now using it as strategic tool to block navigation on a vitally important sea route.

This is a major threat for Ukraine, as our Sea of Azov ports, including Mariupol and Berdyansk, are responsible for an important portion of our international trade.

With this latest attack, Putin effectively has his hands around Ukraine’s throat and is tightening his grip. His ultimate goal is to suffocate and silence us; to see us fail so that he can subsume our country back into a new, emboldened Russian Empire.

But this assault is first and foremost an attack on the Western values that we, Ukrainians, so wholeheartedly share. That Ukrainian people have resolutely chosen to look westward — to the EU, to NATO, to the transatlantic community— is anathema to Putin. He cannot countenance or accept this, which is why he will do whatever he can to destroy Ukraine.

The added benefit, for Putin, is that by keeping the spotlight on us he directs attention away from his significant domestic challenges.

I am thankful for the support that the international community has shown Ukraine, including requests, at the highest diplomatic levels, for the Kremlin to release our captured crew and vessels.

We cannot be deterred by Russia’s typically cynical response to these approaches, and must continue to apply pressure at every level to ensure that, at a minimum, the Kremlin respects international law and ensures our Ukrainian prisoners are treated humanely.

We must also pay attention to the greater Russian threat, which remains hybrid and includes disinformation, social unrest and election meddling. The stakes are increasingly high: As Ukraine prepares for elections next year, Putin will be looking to destabilize, delegitimize and disrupt the process at every possible turn.

Time and again, Ukraine has sought to use the rules of international law to resolve disputes. Russia, by contrast, continues to choose violence, denial and obfuscation.

It is our firm belief that the highly volatile and dangerous situation in the Sea of Azov and Kerch Strait can only be deescalated through solidarity among countries with a shared respect for international law.

For the safety of all of our nations, I urge the international community to maintain its collective pressure on Russia and to demand the immediate release of Ukraine’s captured servicemen.

Pavlo Klimkin is minister for foreign affairs of Ukraine. |

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Nov 26, 2021 21:53:26 GMT 1

In 1991 the Soviet Union collapsed and its Soviet republics became independent states. Among them Ukraine - Poland was the first to acknowledged it.

Superpowers persuaded Ukrainians to give up their nuclear armament which was stationed in its territory,m in exchange for some unclear safety guarantees.

In 2014 Russia invaded Crimea and provoked an anti-Ukrainian revolt in Eastern Ukraine.

Safety guarantees vanished into thin air.

There is a nice proverb - Can you count? Then count on yourself - it is the best option of all.

|

|

|

|

Post by goulangou on Nov 29, 2021 17:59:01 GMT 1

In 1991 the Soviet Union collapsed and its Soviet republics became independent states. Among them Ukraine - Poland was the first to acknowledged it. Superpowers persuaded Ukrainians to give up their nuclear armament which was stationed in its territory,m in exchange for some unclear safety guarantees. In 2014 Russia invaded Crimea and provoked an anti-Ukrainian revolt in Eastern Ukraine. Safety guarantees vanished into thin air. There is a nice proverb - Can you count? Then count on yourself - it is the best option of all. Sad now, put probably right to get them to give up nukes at that time. |

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Dec 10, 2021 21:07:06 GMT 1

Russia threatens Ukraine with a war if Ukrainians continue their advance towards the West. www.onet.pl/informacje/onetwiadomosci/rosja-ukraina-finlandyzacja-analiza-witolda-jurasza/tvwg2p8,79cfc278

Why is Russia escalating the situation around Ukraine. It may be an agreement with the West [ANALYSIS]

The growing tension related to the dislocation of nearly 100,000 Russian soldiers and powerful armored forces near the Ukrainian-Russian border are causing more and more politicians and analysts in the West to publicly wonder whether Europe is in danger of a renewed outbreak of war. Of course, such a scenario is possible, but it is no less likely that Russia is really about an agreement with the West, not a war. The problem, however, is that the agreement that Moscow is proposing may be worse than war, and it is more profitable for the West to risk war than agree with Russia on the terms it proposes.

Witold Jurasz

15.7 thousand

December 6, 2021, 13:49

The costs of the war for Russia and for the Russian elite would probably be so high that war, although possible, is probably not the Kremlin's goal.

All indications are that Moscow wants to offer the West a formal agreement in the form of a treaty on European security, and as a consequence - the new detente (relaxation)

The new détente would limit Ukraine's sovereignty and would probably not apply to Belarus at all. Thus, it would only mean concessions from the West

From Poland's point of view, the threat of both war and, alternatively, a "new Munich" means that Warsaw must repair our relations with the West. But the PiS government, theoretically perceiving the threat from the East, also goes into conflict with the West and thus increases the likelihood of such an agreement between the West and Russia that would ignore our interests

You can find more such stories on the Onet homepage

Advantages of professionalism

Russian foreign policy has several features that make it effective, and from a purely professional point of view, they command respect.

First of all, Russia, unlike Poland, is consistent and pursues the same foreign policy for many years.

Secondly - again unlike Poland - it is able to conduct a consistent foreign policy also because it has a professional diplomatic service and efficient intelligence.

Third, and finally, Russia - unlike Poland again - is aware of its real potential. This means that the Kremlin understands that Russia's importance on the world political scene is gradually diminishing. The Kremlin elite is well aware that the time in which they are able to win relatively much in relations with the West ends with Russia's unchanging technological backwardness and the simultaneous slow, but nevertheless, decline of the world from fossil fuels.

The Russians are quietly but consistently moving large amounts of military equipment near the borders of Ukraine

Russian Foreign Ministry: tensions with the US threaten a repeat of the Cuban crisis

Understanding the above, the hyperrealistic Kremlin elite try to increase Russian assets as long as it is possible, understanding that what else can be obtained today will be impossible to obtain in a dozen years or so. In an attempt to secure, and where possible to increase, the state of ownership, the Russians are masteringly playing well above their real potential.

The rest of the article is available under the video

Why are they doing this? Firstly, by leveraging power, for example through the actions of secret services.

Second, thanks to the bravado of bidding so highly that the unwillingness to take excessive risks, the West often gives way, even when it is actually stronger.

Thirdly, by taking advantage of the naïveté of the West, to which the Russians have prompted, for example, the thesis that if the West does not come to an understanding with Russia, it will become an ally of China. In fact, Russia will never choose China because it understands perfectly well that it would never be able to play Beijing like the West is playing. Contrary to appearances, the Russian elite has long "chosen the West", but firstly on their own terms, and secondly - the West without democracy, human rights, liberalism and the honesty of the people in power. Russian aggression, shoe and arrogance towards the West is, paradoxically, a manifestation of the fact that Russia sees its future not in any alliance with China, but in the framework of the Western world, which - as the Russian elite believes - Russia will be able to force it to accept it on its own conditions.

Reconquest

One of the key elements of Russia's policy towards the West is an attempt to force the West to recognize Russia's right to a reconquest of the post-Soviet space and make it (with the exception of the Baltic states) a Russian sphere of influence or possibly a privileged interest.

This distinction is not just a play on words. In relation to Belarus, Russia's goal is complete domination. In the case of Ukraine, the goals are more limited and boil down to preventing Kiev from becoming part of the West in the future. Russian foreign policy towards Kiev has been consistently pursuing this single goal for years.

SEE: Marine Le Pen in Poland. "Ukraine belongs to Russia's sphere of influence"

When Russia invaded Ukraine in 2014, many commentators said Vladimir Putin had made a mistake because he had "lost" Ukraine. In other words, it is assumed that Vladimir Putin, deciding to start a war with Ukraine, wanted to "regain" it in the sense that he would completely subjugate it and did not understand that the Ukrainians would turn their backs on Russia as a result of the war. In fact, the Russians understood perfectly well that they could never fully control Ukraine again. The aim of unleashing a war was never to "regain" Kiev, but only to prevent the West from "gaining" Ukraine. In a sense, the above has succeeded, because today Ukraine has neither an EU nor a NATO perspective.

The point is, however, that at the same time, since the outbreak of the war, there has been a dramatic change in Ukraine's foreign trade, in which Russia is competing not for the first place with the EU, but also with China. Russia understood that regardless of the fact that Ukraine's prospects of membership in the EU and NATO were blocked, Ukraine's integration with the West is still proceeding. As a result of the above, the Kremlin probably concluded that Kiev was slipping out of Moscow's hands after all. If so, the Kremlin has only done what it can do in such a situation, which is to raise the stakes again.

The Benefits of Theft

Russian troops on the border with Ukraine are a method of negotiating - not with Ukraine, but with the West for the status of Ukraine. Given that Vladimir Putin is becoming less popular and therefore needs success, the fact that the Russians have proved to be deeply dependent on aggressive nationalism, and the Russian officer corps, unlike its Soviet-era predecessors, is often excessively risky, Unfortunately, it cannot be ruled out that Russia will start the war with Ukraine anew.

But it would carry enormous risks for the Russian elite. If we assume that they are driven solely by neo-imperial calculation, such a scenario would be moderately likely. Fortunately, however, the Russian elites, apart from revanchism and neo-imperialism, suffer from a third disease, which is simply unbelievable corruption. The vast majority of the Kremlin's elite, to put it bluntly, steal.

READ: The sharp tensions between Russia and the US. Diplomats disagreed on any issue

This is very bad news for Russia and great news for Poland and the West. The Russian elite keeps the stolen funds not in Chinese, but in Western banks. Any sanctions would severely hit the Russian economy and, more importantly, the interests of the Russian ruling elite. The costs of the war itself and the possible occupation of Ukraine (and - if most of the Ukrainian state are occupied - fighting the guerrillas) are also important.

So while the probability of a war between Russia and the West is close to zero, it is possible to resume fighting on the front with Ukraine. But considering the costs, this is only one of two possible and certainly not the Kremlin's first option. Moscow is not about war.

Relaxation?

The fact that the concentration of Russian troops on the border with Ukraine may be a method of raising the stakes in the negotiations is evidenced by the words of Vladimir Putin, who on Wednesday, December 1, accepting credentials from a dozen newly accredited ambassadors, stated that Russia expects credible guarantees that NATO will not it will expand to the east , that is - to put it bluntly - it will never accept Ukraine into the pact. The Russian president also stated that Moscow expects legal guarantees, which is a reference to the political promises allegedly made by the United States not to extend the pact, which were allegedly broken on the occasion of Poland's admission to NATO.

On the same day, the head of Russian diplomacy, Sergey Lavrov, said during a visit to Stockholm that Russia could respond to NATO's allegedly aggressive actions and "adjust the military-strategic balance of power". In response to Lavrov's statements about the threat of NATO enlargement, US Secretary of State Antony Blinken stated that "the only threat is Russia's renewed aggression against Ukraine."

Ukrainian soldiers at the front in SvitlodarskUkrainian soldiers at the front in Svitlodarsk - PAP / EPA / ANATOLIA STEPANOV

Regardless of the fact that Russia is lying when it comes to the threat posed by NATO, it is worth analyzing Vladimir Putin's words about legal guarantees in detail. These words mean that Russia is proposing to the West to sign a treaty on European security. Its details are yet unclear. It would probably be some variation of Medvedev's already forgotten plan, i.e. a proposal whose essence was, firstly, the division of spheres of influence in Europe, and secondly, an attempt to replace the existing security architecture with a kind of concert of powers, i.e. a system in which Poland, not being a superpower, it would automatically become an object and not a subject of European politics.

Absurdities of Polish politics

At the moment, everything indicates that the likelihood of an agreement between the West and Russia is slim. On the other hand, however, it must be remembered that Russian diplomacy has a unique talent for proposing very general, in practice, far-reaching formulations. Medvedev's plan itself is, by the way, only a slightly refreshed version of the Soviet proposals from the times of Andrei Gromyka. Unfortunately, it cannot be ruled out that in Europe, tired of the new Cold War that has been taking place at least since Vladimir Putin's speech in 2007 in Munich, there will be countries ready to kindly accept any Russian proposals.

France, for example, will certainly be such a state, as it also reacted more favorably to Medvedev's plan a decade and a half ago than, for example, Germany. In this context, it is completely absurd that Polish diplomacy even seems to encourage Paris to be more active in eastern policy, as Jakub Kumoch advised President Duda on foreign affairs recently did in an interview for Dziennik Gazeta Prawna.

The anti-German obsessions of the Polish right do not allow even the president's closest advisers to notice that if there is a country in the European Union and NATO that does not meet all our expectations as far as our attitude towards Russia (like Germany) is concerned, but is simply friendly towards to Russia, this country is precisely France.

Finlandization

On November 24, the editor-in-chief of the bimonthly "Rosija w Globalnoj Politikie", Fyodor Lukyanov, wrote an article in which it was stated that "the positive understanding of the word finlandization must be restored". This was how Finland's status during the Cold War was defined. Although Finland was not in the Soviet sphere of influence, its sovereignty was limited by its inability to join the Western structures. A few sentences earlier, Lukyanov stated explicitly that the principle that the state has the right to join any alliance it wishes to join should be abandoned.

The text of the editor-in-chief of "Russia in Globalnoj Polityka" is very important because Lukyanov, who is often accepted as a liberal in Poland, although in fact he is at most designated a liberal, very often publicly says what Russian diplomacy later proposes. Seemingly finlandization, or in other words: an agreement between the West and Russia on the neutral status of Ukraine and Belarus, could be a quite reasonable solution from the point of view of Poland's interests. We are losing in Belarus. In turn, the EU perspective of Ukraine seems to be more of a mirage than a reality.

New Munich

However, no one is proposing neutrality of Ukraine and Belarus, and the talk about finlandization concerns only Ukraine. Belarus is not mentioned at all, thus treating it as an area of exclusive influence for Moscow.

In Belarus, on the other hand, Russia would sooner or later build its military bases that would allow it to blackmail the Baltic states, force further concessions on Kiev and, finally, threaten Poland. The above means that Poland must be against the agreement and, as a result, relax in relations with Russia on the terms that Russia will most likely propose to the West.

Agreeing to détente on Russian terms would mean that a new Cold War that began with Vladimir Putin's speech in Munich would end with a Munich-style agreement. The one from 1938. As we know, the aggressor was only dared by the 83 years ago. It would be exactly the same this time. If so, then everything must be done to make the possible costs of the war as severe as possible for the aggressor. There is probably something to come to an understanding with Russia, but not on the terms it is proposing.

Understanding the threat of both war and the new Munich, Poland should take care to repair our relations with the West. Otherwise, we may wake up to a reality in which one day a détente in relations with Russia will be announced. But as a result of this relaxation, we will have to arm ourselves. Western bases in Poland will not be established, because we will have "perfect relations" with Russia. The problem is that Poland under PiS rule is going in exactly the opposite direction and instead of repairing relations with the West in the face of the threat from the East, it is doing everything possible to have bad relations with both the East and the West .

The authorities of the Republic of Poland, going to a clash with the West, not only where we have conflicting interests, but even where these interests coincide or there is no reason for a quarrel at all, do exactly what Moscow dreams of, which prefers to negotiate with the non-listening West Warsaw's voice.

We are glad that you are with us. Subscribe to the Onet newsletter to receive the most valuable content from us.

(MBA) 89

Witold Jurasz

Witold Jurasz

president of the Center for Strategic Analysis www.oaspl.org,

Source:

Onet

|

|

|

|

Post by goulangou on Dec 16, 2021 8:53:38 GMT 1

A real danger is that they won't just grab the Russian speaking part in the east, but will push on as far as Moldova. I hope they don't.

We have potentially very difficult times ahead.

|

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Dec 23, 2021 10:54:38 GMT 1

but will push on as far as Moldova. I hope they don't. We have potentially very difficult times ahead. That would be really stupid of the Kremlin. Even if they devour most of Ukraine, they will choke on it sooner or later. Russians are not logical at all. Just like Poles. I think it is a Slavic trait. |

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Jan 5, 2022 16:17:52 GMT 1

The Kremlin is striving to keep Ukraine in their sphere of influence - they demand that NATO and the EU sign up a formal agreement with Russia which states that Ukraine will never be considered a member of these organisations. Russians believe that Ukraine mustn`t be allowed to decide for itself where it wants to belong - the West or East. And such an attitude is unnacceptable. Therefore, NATO and the EU have to do their best to defend Ukraine`s right to act and choose independently. Russians need to cut down on their imperialistic obsessions. They are a superpower in possession of nuclear arsenal so they don`t need to fear any aggression.  |

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Jan 8, 2022 19:13:07 GMT 1

Hypothetical analysis of Russian- Ukrainian war and its effect on Poland businessinsider.com.pl/gospodarka/inwazja-rosji-na-ukraine-oto-jak-odbilaby-sie-na-polskiej-gospodarce/59enfxd

Russia's invasion of Ukraine? Here's how it would affect the Polish economy

Jacek Frączyk

January 5, 2022, 6:09.

The Russian troops stationed near the border with Ukraine may be both a threat to Moscow and the strengthening of its negotiating position with the West, and a real threat to Ukraine. A war abroad could change a lot for Poland, even if we do not get involved in it. In recent years, the role of Ukraine in the Polish economy has been limited not only to sending us employees, but also to the strengthening of economic relations. Lower stability in the region may affect investment decisions in Poland, the zloty exchange rate and the interest rate on government bonds.

Russia has gathered significant armed forces near the border with Ukraine. The possible implementation of the war scenario will affect Poland

Russia may want to take advantage of the moment when Ukraine is still weak and is only just getting out of its problems, says the expert

During the annexation of Crimea eight years ago, the market was selling off the zloty, which was losing not only to the dollar but also to the euro

The cost of Poland's indebtedness did not increase then. This time, however, it may be different, because the plans of central banks are increasing and, according to the expert, it would be better to meet the borrowing needs earlier

- According to US intelligence provided to NATO members, Russia has been preparing for a potential attack on Ukraine for a long time and this threat is real. This is evidenced by both the scale of the disinformation campaign (in Russia - ed.), Which speaks of the alleged threat to Russia from NATO and Ukraine, and the mobilization of 175,000 tactical army and mobilization of an additional 100,000 reservists and the deployment of at least 90 thousand. of them close to the border with Ukraine - says Business Insider to prof. dr hab. Konrad Raczkowski, director of the UKSW World Economy Center, former Deputy Minister of Finance in Beata Szydło's government.

On Sunday , US Senator Adam Schiff from the Democratic Party said the scenario of an armed conflict was "very likely" . However, Piotr Kuczyński, Xelion financial market analyst, does not completely believe in the war in Ukraine.

- I consider such a war to be completely unlikely . Russia's game is about forcing concessions, and no one is considering attacking for a moment. For me, the probability of a war is less than 1 percent, and maybe even a thousand - tells Business Insider.

Marek Rogalski, the main currency analyst at DM BOŚ has a similar impression. - The scenario of a real armed conflict in Ukraine should still be considered unlikely. The Kremlin knows well that the losses would be too great. Nevertheless, the test of strength and constant tension building will continue to achieve goals, such as there may be a pact with NATO to give up joining the former USSR republics to the Alliance - he estimates.

The army stands and waits. For what?

However, approximately 100,000 people are stationed at a distance of up to 200 km from the Ukrainian border since April 2021. soldiers of the Russian army. Back then it was 105,000, in early December the number dropped to 95,000, but a week ago the Ukrainian authorities gave an estimated number of 122,000, and a total of 143,000 within a radius of 400 km. - reported TVN24 last week. In addition, it is estimated that up to 200 km from the border there are over a thousand Russian tanks, 3 thousand. infantry fighting vehicles, almost 2 thousand guns, more than 300 aircraft and more than 200 helicopters. Are these forces only for the purpose of intimidating and forcing concessions from the West, or are they invasive forces? It is difficult to judge about this at the moment.

Ukraine has 140-150 thousand. soldiers - according to the information from the Defence24 portal. Compared to the situation from the times of the annexation of Crimea and the war in Donbas, it is better equipped and has more modern equipment, including, for example, the American Javelin anti-tank missiles, the modernized Soviet Osa and Tor anti-aircraft systems, and the Turkish Bayraktar TB-2 drones. By the way, the latter, which turned out to be very effective in the conflict between Azerbaijan and Armenia, is also to receive the Polish army for over a billion zlotys , and the contract was signed in May 2021.

However, experts point to many weaknesses of the Ukrainian army in the potential conflict with Russia, which it described at the beginning of December last year. German "Bild" . The journal revealed plans for a potential invasion that would take place in January / February this year. An officer interviewed by "Bild" indicates that Javelin missiles would not be enough for all Russian tanks, and Turkish drones do not have sufficient air cover from being destroyed by Russian aviation. Further deliveries of Javelins from Estonia's equipment require the consent of Washington and Berlin, Defence24 reported on Monday.

Putin wants to take advantage of the opportune moment?

- After the style and form of the withdrawal of US troops from Afghanistan, as well as the American focus on China, Moscow will not be driven by fear, but by the opportunity they believe has just emerged, also taking into account the destabilization in Europe and its dependence on Russian gas , the new government in Germany or the April presidential election in France, which, according to the polls of the second round, give more chances to the Republican candidate Valerie Pecresse than to the incumbent President Macron - says prof. Raczkowski.

- Russia has never considered Ukraine an independent territory , and the internal economic and social situation in Russia creates pressure for further escalation of activities. Let us remember that Russia conducted effective military interventions in Georgia and South Ossetia in 2008, in Crimea in 2014, and in Syria in 2015. Thus, it has the ability to make concrete political changes with the use of military force. In turn, the announcements of the United States, the European Union or the G7 regarding sanctions against Russia in the event of an attack do not have any balance or effective deterrence mechanisms, although they would have a negative impact on the Russian economy to some extent, the expert estimates.

ADVERTISEMENT

Is the threat of a conflict in Poland's neighbor real and what would it do for our country? Even if we are not directly threatened by the entry of Russian troops, the entire situation would have an impact on the Polish economy.

Ukraine is developing, among others thanks to Poland

After the annexation of Crimea and the war in Donbas by Ukraine, a political revolution underwent a political revolution and it is not exactly the same country as eight years ago. During this time, millions of Ukrainian emigrants worked in Poland and other European Union countries, supporting their economy with money sent to their homeland.

In 2019, looking at the gross domestic product itself, our eastern neighbor has already made up for the war economic losses , but then it collides with the COVID-19 pandemic. According to IMF forecasts, however, these losses were also made up for last year. and is gearing up for a 3-4% increase in the next five years. As long as Ukraine has a chance for development.

Among other things, thanks to the money sent to the country from emigrants, the economy gained external power and the average GDP per capita in Ukraine , calculated according to the purchasing power parity (including price differences) from 42 percent. the level of Russia in 2013 was reached last year. according to IMF forecasts, up to 46.5 percent. In relation to Belarus, the jump is 56.6 percent. up to 65.9 percent

The comparison with Poland is worse, with 42.4 percent. Polish GDP in 2014, their GDP fell to 37.9 percent. in 2021. Trade contacts with Poland, however, have flourished since then.

The export of goods from Ukraine to Poland has increased since 2013 (the year before the annexation of Crimea) from PLN 7 billion to PLN 11.4 billion in 2020, and the export of services from PLN 1.1 to 1.9 billion. Import of Polish goods to Ukraine increased at the same time from PLN 18 to 23.3 billion, and the import of Polish services from PLN 5.7 to 11.3 billion.

Last year you could see even more acceleration. From January to October, the import of goods from Poland to Ukraine expressed in zlotys increased by 22.4%. y / y, but exports to Poland - by as much as 76 percent. y / y , according to GUS data. In the structure of Polish imports, Ukraine is already 1.6 percent, and in exports from Poland - 2.2 percent.

The higher turnover that the Ukrainian economy is entering after the crisis, despite the occupation of Donbas and Crimea, may, however, be perceived by Moscow as a threat to itself and its recent territorial gains . A stronger economy means greater financial, and thus defense capabilities of Ukraine, the possibility of purchasing better military equipment in the future. And that Ukraine is arming itself, it can be seen, for example, in the export of arms from Poland to this market.

According to GUS data, in January-October last year. it increased by as much as 117 percent. year to year . Poland directed as much as 8.2 percent to Ukraine. of its arms and ammunition exports between January and October 2021, receiving PLN 78 million for these exports.

War would be bad news for Poland as well

In the perception of Russia's power factors, the present moment may be the best to attack, believes Prof. Raczkowski. In the future, this may become more and more difficult as Ukraine continues to strengthen its economic and hence military forces.

- Each military conflict in the area of the borders of a given country has a negative impact on the economy of that country, and in the case of Poland it would be the same . It is not just that a large part of Polish exports would be stopped , which, unfortunately, would become a fact to some extent, assesses the professor of UKSW.

- The risk of interrupting the process of Ukraine's energy synchronization with the EU and the possible suspension of the modernization of the Khmelnitsky nuclear power plant with the participation of the American Westinghouse concern is much greater . Consequently, the threat of electricity imports by Poland from Ukraine, which would be particularly important in the current difficulties of Poland in balancing the national power system - he adds.

He reminds that in 2017 the Minister of Energy of Ukraine offered Poland to buy or build a nuclear power plant in Ukraine, including the ownership of transmission lines.

- And last but not least: employees from Ukraine, with the decreasing number of working Poles, are at least 2 percent. more to our GDP , which we have observed in recent years. Without them, such economic growth would be impossible - he estimates.

The Polish currency market would probably also experience problems. In 2014, when Russia annexed Crimea and the fighting in the Donbas began, the zloty lost 15 percent against the dollar, and 3 percent against the euro. After two consecutive years, the zloty was even lower - by another 15 percent. against the dollar and 2.7 percent. to the euro. The anti-inflationary bill would have wiped out fuel and gas prices if the dollar had risen now as it did then.

- The mere fact of a stronger dollar long after Russia's annexation of Crimea was rather an unrelated coincidence, only the relation of the zloty on global markets and the Fed's actions, assesses Marek Rogalski.

—Nevertheless, if we adopted such a scenario that in a few weeks we see a full-scale armed conflict, it will be unfavorable for the zloty in the short term . Contrary to the situation in 2014/15, now Russia is also using Belarus in a conflict with the West. This could create a risk of greater confusion on the border with Poland, if there was also a mild winter. Looking globally, the single currency in the conflict would lose , because Russia could lead the so-called energy war - comments analyst DM BOŚ.

According to him, they can gain franc as the so-called safe currency and dollar due to US debt.

- Translating it into the zloty, it does not mean, however, that it could lose against the euro. Nevertheless, its increase would be lower than USD PLN or CHF PLN. In the long run, a lot will depend on how the conflict develops, but it does not seem to be a significant thread for more than a few weeks, summarizes Marek Rogalski.

In 2014, credit rating agencies maintained the levels of creditworthiness for Poland. Investments did not break down, and even grew by 10% in 2014. yy. The interest rate on Polish 10-year bonds fell in 2014 from 4.4% to the wave of interest rate cuts. up to 2.5 percent Now, however, it does not have to be so gentle, which is why the implementation of most of the borrowing needs for the entire year in January may, according to prof. Raczyński to protect Poland against a possible escalation of debt servicing costs.

According to information from Deputy Minister of Finance Sebastian Skuza at the end of last year. borrowing needs for 2022 are already met in 40 percent. and the balance of funds in budgetary accounts exceeded PLN 80 billion at the end of the year.

Crimea Ukraine fired without a shot, and then there was a Crimean referendum and annexation to Russia. And in Donbas, Russia did not admit to intervening, so the official narrative still includes the so-called rebellious republic. It would be different if Russia had hit Ukraine openly.

The scenarios talk about possible plans to break through the land corridor to Crimea or cut off Ukraine from the Black Sea, that is, to seize the most industrialized areas as far as Nikolaev and further west to Odessa. Mykolaiv is an important city because the shipyards there used to build Soviet air cruisers, and now it is a naval repair facility. It is also possible to occupy the whole of Ukraine, which would significantly extend our common border with Russia. All this can happen, provided that Russia attacks at all and does not use the army threat as a specific Russian form of negotiation with quite a long tradition. |

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Jan 19, 2022 14:01:03 GMT 1

If mad Putin decides to attack Ukraine, Poland must do its best to help Ukrainians defend their sovereignty. Russians might invade and occupy half of Ukraine but it is natural they are too weak to conquer the whole country, so its Western part which borders with Poland will remain a corridor through which US and West European supplies of defensive weapons can be transported for anti-Russian partisans in Ukrainian occupied territories. Poland must do all to secure the safe and steady flow of that armanent. Ukrainians might lose a few battles against stronger Russians but they must not lose hope that they will win the war. They need to show resilience and determination and give Russian invaders hell wherever and whenever possible. Soon Russians will acquire a nasty dejavu from their occupation of Afghanistan in 20th century where the losses they suffered by brave guerilla fighters made them eventually leave in disgrace. Long live free independent Ukraine!  |

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Jan 21, 2022 14:56:53 GMT 1

If Russians invade and occupy Ukraine and install their troops in Belarus, Poland will become a front country, like West Germany during the Cold War. www.onet.pl/informacje/onetwiadomosci/jurasz-mozliwe-scenariusze-rozwoju-konfliktu-rosja-ukraina-analiza/gjfsvp5,79cfc278

Jurasz: Poland as a new West Germany, or possible scenarios for the development of the Russia-Ukraine conflict [ANALYSIS]

There are at least three scenarios for the development of the situation between Russia and Ukraine, and according to one of them, we can become the new West Germany of the new Cold War - a front-line state under the special protection of the West.

Witold Jurasz

17.2 thousand

Yesterday, 06:57

One of the reasons for the threat to Ukraine is the defeat of the revolution in Belarus

If you imagine a limited Russian invasion of Ukraine or even the lack of such an attack, then given the scale of Russian domination over Belarus, Poland will be militarily threatened anyway

The hysteria about the imminent "betrayal of the West" is an expression of obsession, and it only pays off for Russia, and who knows if Russia is not inspiring her

More information on the crisis on the border between Russia and Ukraine can be found on the main page of Onet.pl

The interests of the Kremlin's kleptocratic ruling elite have been intertwined with Russia's national interests for years. The interests of the elite, in a situation where it is almost impossible to reform the state at all, and the nation can be given less bread than before, make it necessary to play the games. This means that the likelihood of war is increasing.

At the same time, however, the same interests force the Kremlin elite to play hard enough to give the Russians addicted to imperialism the drug of victory, but not so harshly as to expose themselves to Western sanctions. This in turn indicates a greater likelihood of a "small war" rather than a full-scale war.

What could happen? Three scenarios

Any attempt to predict the development of events without access to intelligence is practically impossible. But there are three scenarios. Perhaps Putin, when attacking Ukraine, will "only" want to connect Donbass, controlled by pro-Russian separatists, with Russian-occupied Ukrainian Crimea. Or maybe it will go further and take over Odessa as well, linking Donbass with Transnistria (part of Moldova controlled by the Russians), while also completely cutting Ukraine off from the sea.

However, a full-scale war scenario cannot be ruled out either. In this variant, Putin will want to take Kiev, and who knows if he will not try to conquer all of Ukraine - in such a scenario, the Russians will have to deal with Ukrainian guerrillas. There will be only one effect for Poland. We will border in the east with Russia's Kaliningrad District, theoretically only independent Belarus and Russian-occupied Ukraine.

Either of these scenarios is possible, although the most far-reaching ones are of course less likely.

A full-scale war is, of course, a drama for both Ukrainians and Ukraine, probably hundreds of thousands of refugees from Ukraine on our borders, and the complete destabilization of the situation in our region. The problem is that, for example, from the words of US President Joe Biden at a press conference on January 19, it is clear that if the Russians confine themselves to a "little war", the West may prove to be politically incapable of reacting hard.

In such a scenario, taking into account the scale of Russian domination over Belarus, will be militarily threatened anyway. At the same time, there will certainly be those in Berlin, Paris, Madrid and Rome who will opt for the lifting of sanctions against Russia in a few years' time. In Poland, there will be as many American soldiers stationed as there are currently (or possibly 2-3 thousand more).

However, if you imagine a full-scale war and a roughly 200,000 Russian army entering Ukraine, Russian artillery shelling Ukrainian cities and recordings of Russian war crimes (because Russia always commits during the war), Poland has a chance to become the equivalent of West Germany with cold war times.

This will mean the stationing of not a few, but probably tens of thousands of allied soldiers in Poland, the creation of armor warehouses, and ideally also the dislocation of American nuclear weapons in Poland.

The prospect of such a prospect will surely give many people shivers down their spine, but it is worth realizing that the status of the new West Germany of the new Cold War is as much as a sign on the border: "State protected by the United States."

Putin is almost 70 years old. But his age does not matter, because the problem is the Russians, not Putin

Vladimir Putin turns 70 this year. Maybe he will stay on the Kremlin throne for a few more, maybe a dozen or so years. The thing is, it doesn't matter.

Russia has openly threatened to attack Ukraine for three months. During all this time, neither in Moscow nor in any other Russian city there was any significant protest (and - let us recall - even in Soviet times there were brave people who protested against the intervention in Czechoslovakia in 1968). The conclusion from this is, unfortunately, that the Russians either like, or at least do not mind, threatening Ukraine with war.

The Russians, not Putin, are the problem, and their aggressive nationalism will outlive Putin. If so, then neither the Russians as people nor Russia as a state can be trusted. And it is better to have in your territory not 5, but 25 or 55 thousand. American soldiers.

No, there will be no "betrayal of the West"

What is happening beyond our eastern border leads to another conclusion: contrary to conspiracy theories, the West neither intends nor has any reason to betray or sell Poland.

The constant threat of "betrayal of the West" looks more and more like a psychological operation inspired by Russia, which is to lead us to the conclusion that if this West will inevitably betray us, we can - before that happens - turn our backs on the West. It is worth stopping hysterical in the end.

Better American cowboy than pro-Russian France

At the same time, however, the same West has been showing weakness and indecisiveness towards Russia for years. This is largely the fault of Germany, which the German elite seems to be becoming aware of.

However, before we blame the Germans for all the sins of the West, as we happily do in Poland, it is worth remembering that Germany - even taking into account its attitude towards the Nord Stream - was much more critical of Russia than, for example, the traditionally pro-Russian France.

See also: Prime Minister of Canada: Russia is looking for an excuse to increase aggression against Ukraine

The ideas of President Andrzej Duda's advisers to encourage France to participate more actively in eastern policy (because, you know, Germany cannot be trusted in this direction) is not trying to replace Minister Adam Niedzielski with MP Janusz Kowalski.

If we are to stay with someone in Europe, it is with Germany, not France. Above all, let's keep with the US. For if there is any country that Russia takes into account and fears - it is the United States.

The fact that Washington and Moscow are talking about the future of Europe shows what a political dwarf the European Union remains. It would be good to start changing that.

However, when it comes to security issues, it is better for Washington, not Paris, to be its guarantor.

We lost in Belarus

Poland was neither betrayed nor sold by anyone. The situation is worse with Ukraine. All indications are that she betrayed Ukraine, above all, Belarus. Western analysts are concerned about how deadly it would be for the Ukrainian capital to be attacked simultaneously from the east and the north, i.e. from the territory of Belarus.

On Onet we wrote about this scenario many times. Earlier, we alarmed, even before there was even an attempt to carry out a revolution in Belarus, that it could bring deplorable consequences for Poland. For if the alternative to Lukashenka was not democracy, but Lukashenko, completely subordinated to Russia, then the Belarusian revolution simply did not pay off in Poland. Realism, however, lost out to Romanticism in Poland.

After a year and a half, you can see who was right. However, those who were ready to support the protests in Belarus, regardless of their consequences, do not see it. More and more often you hear the narrative that Poland actually won in Belarus, because if Lukashenka was left with bare strength, it means that he lost.

And we, since the Belarusians are allegedly turning their backs on Russia and want democracy, have won. It is a pity that in NATO Headquarters this "victory" must now be marked on the staff maps - arrows showing where Russia can attack Kiev are now also moving out of Belarus.

|

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Mar 20, 2022 20:01:22 GMT 1

Just read a nice saying: Ukrainians have lost their bigger brother - Russia. For ever. However, they have also gained a sister - Poland. Beautiful words.   |

|