Post by tufta on Aug 28, 2010 7:53:35 GMT 1

Sorbs, also known as Wends, Lusatian Sorbs or Lusatian Serbs, are a Western Slavic people of Central Europe living predominantly in Lusatia, a region on the territory of Germany and Poland. In Germany they live in the states of Brandenburg and Saxony. They speak the Sorbian languages (Wendish, Lusatian), closely related to Polish, Kashubian, Czech and Slovak and officially recognized and protected as minority languages of Germany, but due to Germanization only the older generation in Lower Sorbia speak the language at home. Their religions are predominantly Catholicism and Lutheranism. Sorbs are divided into two geographical groups:

* Upper Sorbs, who speak Upper Sorbian

* Lower Sorbs, who speak Lower Sorbian

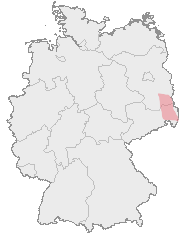

Small region where the Sorbs still live in Germany, the area that used to be much larger in the past

History of the Sorbs

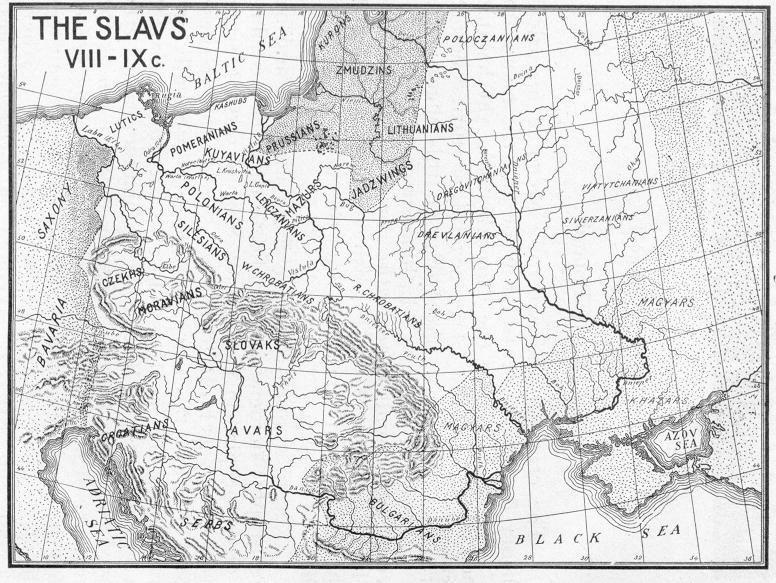

During the 6th century A.D., Sorbs arrived in the area extending between the Bober, Kwisa and Oder rivers to the East and the Saale and Elbe rivers to the West. In the North, the area of their settlement reached Berlin. In 631 A.D., for the first time, the Fredegar’s Chronicle described them as Surbi. Annales Regni Francorum mention that in 806 A.D., Miliduch (the Sorbian King) fought against the Francs and was killed. In 932 Henry I conquered Lusatia and Milsko. In 933 Lusatia was again conquered by Gero II – the Margrave of the Saxon Ostmark, who in 939 treacherously murdered 30 Sorbian princes during the feast. As a result, there were many Sorbian uprisings against the Germans.

From this early period there remains only a reconstructed castle —Raddusch in Lower Lusatia. During the reign of Boleslaw I of Poland in 1002-1018, three Polish-German wars were waged which caused Lusatia to come under the domination of new rulers. In 1018, on the strength of peace in Bautzen, Lusatia became a part of Poland; however, before 1031 it was returned to Germany. From the 11th to the 15th century, agriculture in Lusatia developed and colonization by Frankish, Flemish and Saxon settlers intensified. In 1327 the first prohibitions on using Sorbian in Altenburg, Zwickau and Leipzig appeared. Between 1376 and 1635 Lusatia was again part of an Empire, under the rule of the Bohemian Luxembourgs, part of Saint Waclav's Crown. At the beginning of the 16th century the whole Sorbian area, with the exception of Lusatia, underwent Germanization.

The Thirty Years War and the Black Death caused terrible devastation in Lusatia: almost half the Sorbs died. This led to further German colonization and Germanization. In 1667 the Prince of Brandenburg, Frederick Wilhelm, ordered the immediate destruction of all Sorbian printed materials and banned saying masses in this language. At the same time the Evangelical Church supported printing Sorbian religious literature as a means of fighting the Counterreformation. In 1706 the Sorbian Seminary, the main centre for the education of Sorbian Catholic priests, was founded in Prague. Evangelical students of theology formed the Sorbian College of Ministers.

The Congress of Vienna, in 1815, gave part of Upper Lusatia to Saxony, but most of Lusatia to Prussia. More and more bans on the use of Sorbian languages appeared from then until 1835 in Saxony and Prussia; emigration of the Sorbs, mainly to the town of Serbin in Texas and to Australia, increased. In 1848, 5000 Sorbs signed a petition to the Saxon Government, in which they demanded equality for the Sorbian language with the German one in churches, courts, schools and Government departments. From 1871 the whole of Lusatia became a part of united Germany and was divided between two parts; Prussia (Silesia and Brandenburg), and Saxony.

From 1871 the industrialization of the region and German immigration began; official Germanization intensified. Although the Weimar Republic guaranteed constitutional minority rights, it did not practice them.

Throughout The Third Reich, Sorbians were described as a German tribe who spoke a Slavic language and their national poet Handrij Zejler as German as well. Sorbian costume, culture, customs and even the language was said to be no indication of a non-German origin. The Reich declared that there were truly no "Sorbs" or "Lusatians", only Wendish-Speaking Germans. As such, the cultivation of "Wendish" customs and traditions was to be encouraged in a controlled manner and the Slavic language would decline due to natural causes. Young Sorbs enlisted in the Wehrmacht and were sent to the front. Entangled lives of the Sorbs during World War II are exemplified by life stories of Mina Witkojc, Měrčin Nowak-Njechorński and Jan Skala.

The first Lusatian cities were captured in April 1945, when the Red Army and the Polish Second Army crossed the river Queis (Kwisa). The defeat of Nazi Germany changed the Sorbs’ situation considerably: those to the east of Neisse and Oder were expelled or assimilated by Poland. The regions in East Germany (the German Democratic Republic) faced a large influx of expelled Germans and heavy industrialisation, which both forced Germanization. The East German authorities tried to counteract this development by creating a broad range of Sorbian institutions. The Sorbs were officially recognized as an ethnic minority, more than 100 Sorbian schools and several academic institutions were founded, the Domowina and its associated societies were re-established and a Sorbian theatre was created. Owing to the oppression of the church and forced collectivization, however, these efforts were severely affected and consequently over time the number of people speaking Sorbian languages decreased by half.

Sorbian Slovians caused the communist government of the GDR (the German Democratic Republic) plenty of trouble, mainly because of the high levels of religious observance and resistance to the nationalisation of agriculture. During the compulsory collectivization campaign, a great many unprecedented incidents were reported. Thus, throughout the Uprising of 1953 in East Germany, violent clashes with the police were reported in Lusatia. An open uprising took place in three upper communes of Błot.

After the unification of Germany on 3 October 1990, Lusatians made efforts to create an autonomous administrative unit; however Helmut Kohl’s government did not agree to it. After 1989 the Sorbian movement revived, however it still encounters many obstacles. Although Germany supports national minorities, Sorbs claim that their aspirations are not sufficiently fulfilled. The desire to unite Lusatia into one country has not been taken into consideration. Upper Lusatia still belongs to Saxony and Lower Lusatia to Brandenburg. Liquidations of Sorbian schools, even in areas mostly populated by Sorbs, still happen, under the pretext of financial difficulties or demolition of whole villages to create lignite quarries.

Today (2008) Sorbian institutions serving 60,000 Sorb people supposedly receive less money for preservation of their culture than one German theater's yearly budget in BerliN, an annual state grant of 15.6 million Euro by the Federal and the Saxon governments. Faced with growing threat of cultural extincton the Domowina issued a memorandum in March 2008 and called for "help and protection against the growing threat of their cultural extinction, since an ongoing conflict between the German government, Saxony and Brandenburg about the financial distribution of help blocks the financing of almost all Sorbian institutions". The memorandum also demands a reorganisation of competence by ceding responsibility from the Länder to the federal government and an expanded legal status. The call has been issued to all governments and heads of state of the European Union.

Besides the memorandum, Sorbs also called on Poland and former Polish President Lech Kaczynski for protection and to represent them in talks with German state as unlike for example Danes have no state to help them against German authorities, as Jan Nuck stated "I think if Angela Merkel speaks about German minority rights in Poland to Lech Kaczynski, then the Polish President should demand the same about us". Nuck also said that the rights of Sorb people are not respected in German "Federal government and land government don't respect them(rights)" A further appeal has been made to Polish Embassy in Berlin using the histrionic language of Pan-Slavism, starting with "Help us. Do something for us. Our culture is dying. We are dying out. Slavs should help each other". Jan Nuck says it is difficult to judge if the situation comes from indifference of officials or if it is a concentrated effort aiming against existence of Sorb national identity in Germany.

* Upper Sorbs, who speak Upper Sorbian

* Lower Sorbs, who speak Lower Sorbian

Small region where the Sorbs still live in Germany, the area that used to be much larger in the past

History of the Sorbs

During the 6th century A.D., Sorbs arrived in the area extending between the Bober, Kwisa and Oder rivers to the East and the Saale and Elbe rivers to the West. In the North, the area of their settlement reached Berlin. In 631 A.D., for the first time, the Fredegar’s Chronicle described them as Surbi. Annales Regni Francorum mention that in 806 A.D., Miliduch (the Sorbian King) fought against the Francs and was killed. In 932 Henry I conquered Lusatia and Milsko. In 933 Lusatia was again conquered by Gero II – the Margrave of the Saxon Ostmark, who in 939 treacherously murdered 30 Sorbian princes during the feast. As a result, there were many Sorbian uprisings against the Germans.

From this early period there remains only a reconstructed castle —Raddusch in Lower Lusatia. During the reign of Boleslaw I of Poland in 1002-1018, three Polish-German wars were waged which caused Lusatia to come under the domination of new rulers. In 1018, on the strength of peace in Bautzen, Lusatia became a part of Poland; however, before 1031 it was returned to Germany. From the 11th to the 15th century, agriculture in Lusatia developed and colonization by Frankish, Flemish and Saxon settlers intensified. In 1327 the first prohibitions on using Sorbian in Altenburg, Zwickau and Leipzig appeared. Between 1376 and 1635 Lusatia was again part of an Empire, under the rule of the Bohemian Luxembourgs, part of Saint Waclav's Crown. At the beginning of the 16th century the whole Sorbian area, with the exception of Lusatia, underwent Germanization.

The Thirty Years War and the Black Death caused terrible devastation in Lusatia: almost half the Sorbs died. This led to further German colonization and Germanization. In 1667 the Prince of Brandenburg, Frederick Wilhelm, ordered the immediate destruction of all Sorbian printed materials and banned saying masses in this language. At the same time the Evangelical Church supported printing Sorbian religious literature as a means of fighting the Counterreformation. In 1706 the Sorbian Seminary, the main centre for the education of Sorbian Catholic priests, was founded in Prague. Evangelical students of theology formed the Sorbian College of Ministers.

The Congress of Vienna, in 1815, gave part of Upper Lusatia to Saxony, but most of Lusatia to Prussia. More and more bans on the use of Sorbian languages appeared from then until 1835 in Saxony and Prussia; emigration of the Sorbs, mainly to the town of Serbin in Texas and to Australia, increased. In 1848, 5000 Sorbs signed a petition to the Saxon Government, in which they demanded equality for the Sorbian language with the German one in churches, courts, schools and Government departments. From 1871 the whole of Lusatia became a part of united Germany and was divided between two parts; Prussia (Silesia and Brandenburg), and Saxony.

From 1871 the industrialization of the region and German immigration began; official Germanization intensified. Although the Weimar Republic guaranteed constitutional minority rights, it did not practice them.

Throughout The Third Reich, Sorbians were described as a German tribe who spoke a Slavic language and their national poet Handrij Zejler as German as well. Sorbian costume, culture, customs and even the language was said to be no indication of a non-German origin. The Reich declared that there were truly no "Sorbs" or "Lusatians", only Wendish-Speaking Germans. As such, the cultivation of "Wendish" customs and traditions was to be encouraged in a controlled manner and the Slavic language would decline due to natural causes. Young Sorbs enlisted in the Wehrmacht and were sent to the front. Entangled lives of the Sorbs during World War II are exemplified by life stories of Mina Witkojc, Měrčin Nowak-Njechorński and Jan Skala.

The first Lusatian cities were captured in April 1945, when the Red Army and the Polish Second Army crossed the river Queis (Kwisa). The defeat of Nazi Germany changed the Sorbs’ situation considerably: those to the east of Neisse and Oder were expelled or assimilated by Poland. The regions in East Germany (the German Democratic Republic) faced a large influx of expelled Germans and heavy industrialisation, which both forced Germanization. The East German authorities tried to counteract this development by creating a broad range of Sorbian institutions. The Sorbs were officially recognized as an ethnic minority, more than 100 Sorbian schools and several academic institutions were founded, the Domowina and its associated societies were re-established and a Sorbian theatre was created. Owing to the oppression of the church and forced collectivization, however, these efforts were severely affected and consequently over time the number of people speaking Sorbian languages decreased by half.

Sorbian Slovians caused the communist government of the GDR (the German Democratic Republic) plenty of trouble, mainly because of the high levels of religious observance and resistance to the nationalisation of agriculture. During the compulsory collectivization campaign, a great many unprecedented incidents were reported. Thus, throughout the Uprising of 1953 in East Germany, violent clashes with the police were reported in Lusatia. An open uprising took place in three upper communes of Błot.

After the unification of Germany on 3 October 1990, Lusatians made efforts to create an autonomous administrative unit; however Helmut Kohl’s government did not agree to it. After 1989 the Sorbian movement revived, however it still encounters many obstacles. Although Germany supports national minorities, Sorbs claim that their aspirations are not sufficiently fulfilled. The desire to unite Lusatia into one country has not been taken into consideration. Upper Lusatia still belongs to Saxony and Lower Lusatia to Brandenburg. Liquidations of Sorbian schools, even in areas mostly populated by Sorbs, still happen, under the pretext of financial difficulties or demolition of whole villages to create lignite quarries.

Today (2008) Sorbian institutions serving 60,000 Sorb people supposedly receive less money for preservation of their culture than one German theater's yearly budget in BerliN, an annual state grant of 15.6 million Euro by the Federal and the Saxon governments. Faced with growing threat of cultural extincton the Domowina issued a memorandum in March 2008 and called for "help and protection against the growing threat of their cultural extinction, since an ongoing conflict between the German government, Saxony and Brandenburg about the financial distribution of help blocks the financing of almost all Sorbian institutions". The memorandum also demands a reorganisation of competence by ceding responsibility from the Länder to the federal government and an expanded legal status. The call has been issued to all governments and heads of state of the European Union.

Besides the memorandum, Sorbs also called on Poland and former Polish President Lech Kaczynski for protection and to represent them in talks with German state as unlike for example Danes have no state to help them against German authorities, as Jan Nuck stated "I think if Angela Merkel speaks about German minority rights in Poland to Lech Kaczynski, then the Polish President should demand the same about us". Nuck also said that the rights of Sorb people are not respected in German "Federal government and land government don't respect them(rights)" A further appeal has been made to Polish Embassy in Berlin using the histrionic language of Pan-Slavism, starting with "Help us. Do something for us. Our culture is dying. We are dying out. Slavs should help each other". Jan Nuck says it is difficult to judge if the situation comes from indifference of officials or if it is a concentrated effort aiming against existence of Sorb national identity in Germany.