Post by Bonobo on Aug 30, 2010 20:08:19 GMT 1

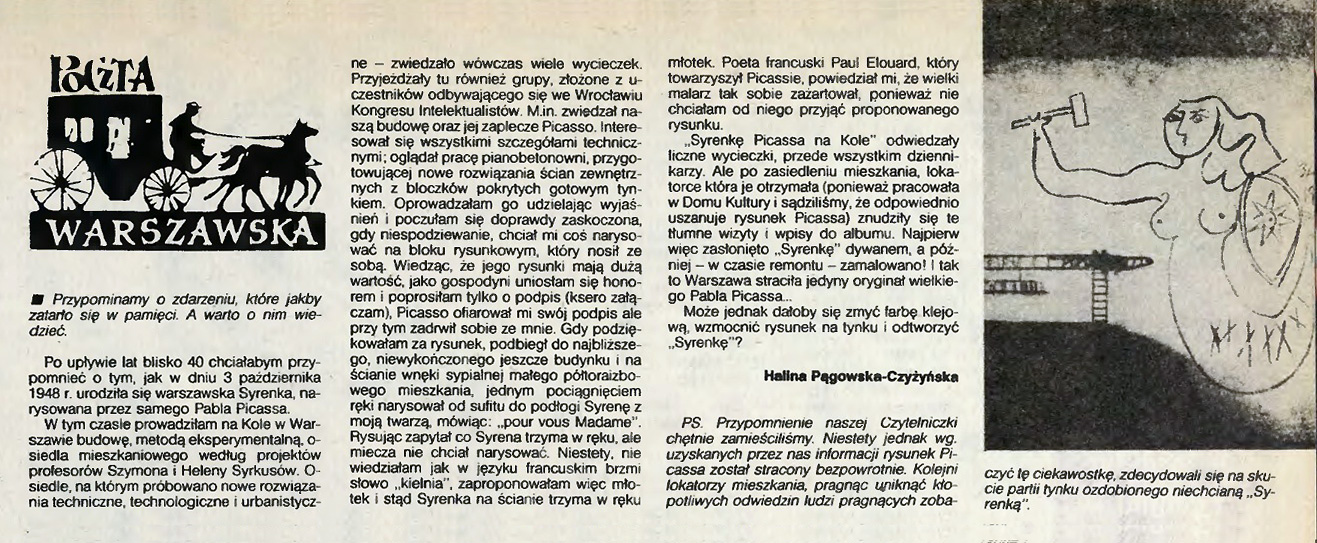

In 1948, Pablo Picasso, a famous painter, was a member on the French communist party. As such, he was invited to Poland to some communist congress. He saw the rebuilding of Warsaw and was fascinated with it. He drew a picture of Warsaw Mermaid holding a hammer instead of a sword in one of newly constructed apartments. The tennants who lived there couldn`t bear the invasion of guests coming to see the picture every day, so after a few years they washed the Mermaid from the wall.

What a pity!

Here is tennant`s story:

FRANCISZKA S., pensioner

On modern art

...They took him to the still unfinished building. He liked it and went inside, asked for a ladder and took a black pencil from his pocket. He drew a mermaid . On the wall. Everyone was very happy and thanked him. And then they went away, and the mermaid stayed.

They assigned the flat to a railway worker. He looked around, and said that firstly it was inadequate and secondly he had small children, and she had bare breasts. So he didn’t take it, and they called me. I didn’t have any children or any points – the only thing I could have scored on was my activity in the food cooperative, but I wasn’t even a member of it, so when they said there was a flat, I rushed over there.

They told me to sit down. You see – the director said – this isn’t an ordinary apartment, it’s one with a mermaid. Fine, I said. And you see, this apartment must be kept clean, because visitors might come by. I’ll keep it clean, I promised; got the keys, opened the door…

My dear madam, what can I say?

It was a Picasso.

It was huge, my God was it huge. Her bosom was like two balloons, the eyes were triangular, at the end of her long, oddly long arm she held a hammer; and she had a short, tapering tail at the back.

We only had a sofa bed and a table. The table stood in the middle of the room and the sofa bed against the wall, with the hammer hanging over our heads. When we woke up, we saw her eyes, even odder than her arm and the tail.

A group from China was the first to arrive. They were visiting Polish workers’ housing estates. After the Chinese came the miners, festive in their plumed hats. Then came the textile workers, they were labour heroes. I was polite – I knew I was representing our capital city – but inside I seethed. Especially when I looked at their boots and calculated how much muck I would have to take out that day.

The parliamentary speaker came to see us – tell me, comrades, aren’t you afraid to be with her, alone as it were? – he asked in the hallway. The president came and looked, but didn’t say a word. The gentlemen from the ministry came, took measurements and exchanged opinions. Maybe we could take it off together with the plaster? Aw, come on, it’s too delicate. Put it behind glass? Aw, come on, the frame wouldn’t hold up…

They got on our nerves. We hired a painter. The painter brought a bucket and soap.

It was only when he died and they started talking about the quarrels between his children that we thought: perhaps it wasn’t such a good idea…? We were motivated by public interest, for the mermaid was state owned, and we would have got nothing out of it. Like our tattered couch, for which were weren’t given a single cent in compensation.

The people from the ministry came again. They brought machines with them and x-rayed the wall. Gentlemen, don’t trouble yourselves, I said. It was a good, pre-war workman and good, ordinary soap.

What a pity!

Here is tennant`s story:

FRANCISZKA S., pensioner

On modern art

...They took him to the still unfinished building. He liked it and went inside, asked for a ladder and took a black pencil from his pocket. He drew a mermaid . On the wall. Everyone was very happy and thanked him. And then they went away, and the mermaid stayed.

They assigned the flat to a railway worker. He looked around, and said that firstly it was inadequate and secondly he had small children, and she had bare breasts. So he didn’t take it, and they called me. I didn’t have any children or any points – the only thing I could have scored on was my activity in the food cooperative, but I wasn’t even a member of it, so when they said there was a flat, I rushed over there.

They told me to sit down. You see – the director said – this isn’t an ordinary apartment, it’s one with a mermaid. Fine, I said. And you see, this apartment must be kept clean, because visitors might come by. I’ll keep it clean, I promised; got the keys, opened the door…

My dear madam, what can I say?

It was a Picasso.

It was huge, my God was it huge. Her bosom was like two balloons, the eyes were triangular, at the end of her long, oddly long arm she held a hammer; and she had a short, tapering tail at the back.

We only had a sofa bed and a table. The table stood in the middle of the room and the sofa bed against the wall, with the hammer hanging over our heads. When we woke up, we saw her eyes, even odder than her arm and the tail.

A group from China was the first to arrive. They were visiting Polish workers’ housing estates. After the Chinese came the miners, festive in their plumed hats. Then came the textile workers, they were labour heroes. I was polite – I knew I was representing our capital city – but inside I seethed. Especially when I looked at their boots and calculated how much muck I would have to take out that day.

The parliamentary speaker came to see us – tell me, comrades, aren’t you afraid to be with her, alone as it were? – he asked in the hallway. The president came and looked, but didn’t say a word. The gentlemen from the ministry came, took measurements and exchanged opinions. Maybe we could take it off together with the plaster? Aw, come on, it’s too delicate. Put it behind glass? Aw, come on, the frame wouldn’t hold up…

They got on our nerves. We hired a painter. The painter brought a bucket and soap.

It was only when he died and they started talking about the quarrels between his children that we thought: perhaps it wasn’t such a good idea…? We were motivated by public interest, for the mermaid was state owned, and we would have got nothing out of it. Like our tattered couch, for which were weren’t given a single cent in compensation.

The people from the ministry came again. They brought machines with them and x-rayed the wall. Gentlemen, don’t trouble yourselves, I said. It was a good, pre-war workman and good, ordinary soap.