|

|

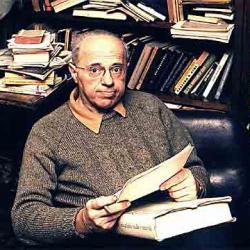

Post by Bonobo on Jan 25, 2008 22:18:27 GMT 1

It is no accident that Stanisław Lem opens the thread about Polish literature. He was the author whose books I read most. I already knew them when at my primary school. Later, one day, my mother bought a big box of cheap second-hand books from a drunk at a flea-market. He probably liked science fiction literature because most of those books were by Lem, Clarke,. I had a feast with them for many years. www.lem.pl/cyberiadinfo/english/kiosk/kiosk.htmStanislaw Lem was born in Lvov, Poland in 1921. His short stories were first published in a magazine specializing in modern prose and science-fiction. Subsequent books gained him world-wide acclaim and Solaris, His Master's Voice and The Cyberiad belong to the most famous science-fiction works of the twentieth century. Lem's books were translated into forty languages, these editions total over twenty seven million copies. The particular value of Lem's works lies in the combination of sensory richness of fantastic visions with first-class scientific knowledge and a truly philosophical mind. Today Lem is regarded not only as an outstanding science-fiction writer but also as a philosopher, a humanist and a universal thinker. |

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Jan 25, 2008 22:20:42 GMT 1

How The World Was Saved (a fragment of The Cyberiad, 1965 www.lem.pl/english/dziela/cyberiada/cyberiadapl.htm One day Trurl the constructor put together a machine that could create anything starting with n. When it was ready, he tried it out, ordering it to make needles, then nankeens and negligees, which it did, then nail the lot to narghiles filled with nepenthe and numerous other narcotics. The machine carried out his instructions to the letter. Still not completely sure of its ability, he had it produce, one after the other, nimbuses, noodles, nuclei, neutrons, naphtha, noses, nymphs, naiads, and natrium. 'This last it could not do, and Trurl, considerably irritated, demanded an explanation. "Never heard of it," said the machine.Trurl's Machine "What? But it's only sodium. You know, the metal, the element..." "Sodium starts with an s, and I work only in n." "But in Latin it's natrium." "Look, old boy," said the machine, "if I could do everything starting with n in every possible language, I'd be a Machine That Could Do Everything in the Whole Alphabet, since any item you care to mention undoubtedly starts with n in one foreign language or another. It's not that easy. I can't go beyond what you programmed. So no sodium." "Very well," said Trurl and ordered it to make Night, which it made at once - small perhaps, but perfectly nocturnal. Only then did Trurl invite over his friend Klapaucius the constructor, and introduced him to the machine, praising its extraordinary skill at such length, that Klapaucius grew annoyed and inquired whether he too might not test the machine. "Be my guest," said Trurl. "But it has to start with n." "N?" said Klapaucius. "All right, let it make Nature." The machine whined, and in a trice Trurl's front yard was packed with naturalists. They argued, each publishing heavy volumes, which the others tore to pieces; in the distance one could see flaming pyres, on which martyrs to Nature were sizzling; there was thunder, and strange mushroom-shaped columns of smoke rose up; everyone talked at once, no one listened, and there were all sorts of memoranda, appeals, subpoenas and other documents, while off to the side sat a few old men, feverishly scribbling on scraps of paper. "Not bad, eh?" said Trurl with pride. "Nature to a T, admit it!" But Klapaucius wasn't satisfied. "What, that mob? Surely you're not going to tell me that's Nature?" "Then give the machine something else," snapped Trurl. "Whatever you like." For a moment Klapaucius was at a loss for what to ask. But after a little thought he declared that he would put two more tasks to the machine; if it could fulfill them, he would admit that it was all Trurl said it was. Trurl agreed to this, whereupon Klapaucius requested Negative. "Negative?!" cried Trurl. "What on earth is Negative?" "The opposite of positive, of course," Klapaucius coolly replied. "Negative attitudes, the negative of a picture, for example. Now don't try to pretend you never heard of Negative. All right, machine, get to work!" The machine, however, had already begun. First it manufactured antiprotons, then antielectrons, antineutrons, antineutrinos, and labored on, until from out of all this antimatter an antiworld took shape, glowing like a ghostly cloud above their heads. "H'm," muttered Klapaucius, displeased. "That's supposed to be Negative? Well... let's say it is, for the sake of peace. . . . But now here's the third command: Machine, do Nothing!" The machine sat still. Klapaucius rubbed his hands in triumph, but Trurl said: . "Well, what did you expect? You asked it to do nothing, and it's doing nothing." "Correction: I asked it to do Nothing, but it's doing nothing." "Nothing is nothing!" "Come, come. It was supposed to do Nothing, but it hasn't done anything, and therefore I've won. For Nothing, my dear and clever colleague, is not your run-of-the-mill nothing, the result of idleness and inactivity, but dynamic, aggressive Nothingness, that is to say, perfect, unique, ubiquitous, in other words Nonexistence, ultimate and supreme, in its very own nonperson!" "You're confusing the machine!" cried Trurl. But suddenly its metallic voice rang out: "Really, how can you two bicker at a time like this? Oh yes, I know what Nothing is, and Nothingness, Nonexistence, Nonentity, Negation, Nullity and Nihility, since all these come under the heading of n, n as in Nil. Look then upon your world for the last time, gentlemen! Soon it shall no longer be..." The constructors froze, forgetting their quarrel, for the machine was in actual fact doing Nothing, and it did it in this fashion: one by one, various things were removed from the world, and the things, thus removed, ceased to exist, as if they had never been. The machine had already disposed of nolars, nightzebs, nocs, necs, nallyrakers, neotremes and nonmalrigers. At moments, though, it seemed that instead of reducing, diminishing and subtracting, the machine was increasing, enhancing and adding, since it liquidated, in turn: nonconformists, nonentities, nonsense, nonsupport, nears ightedness, narrowmindedness, naughtiness, neglect, nausea, necrophdia and nepotism. But after a while the world very definitely began to thin out around Trurl and Klapaucius. "Omigosh!" said Trurl. "If only nothing bad comes out of all this . . ."Trurl "Don't worry," said Klapaucius. "You can see it's not producing Universal Nothingness, but only causing the absence of whatever starts with n. Which is really nothing in the way of nothing, and nothing is what your machine, dear Trurl, is worth!" "Do not be deceived," replied the machine. "I've begun, it's true, with everything in n, but only out of familiarity. To create however is one thing, to destroy, another thing entirely. I can blot out the world for the simple reason that I'm able to do anything and everything - and everything means everything - in n, and consequently Nothingness is child's play for me. In less than a minute now you will cease to have existence, along with everything else, so tell me now, Klapaucius, and quickly, that I am really and truly everything I was programmed to be, before it is too late." "But -" Klapaucius was about to protest, but noticed, just then, that a number of things were indeed disappearing, and not merely those that started with n. The constructors were no longer surrounded by the gruncheons, the targalisks, the shupops, the calinatifacts, the thists, worches and pritons. "Stop! I take it all back! Desist! Whoa! Don't do Nothing!!" screamed Klapaucius. But before the machine could come to a full stop, all the brashations, plusters, laries and zits had vanished away. Now the machine stood motionless. The world was a dreadful sight. The sky had particularly suffered: there were only a few, isolated points of light in the heavens - no trace of the glorious worches and zits that had, till now, graced the horizon! "Great Gauss!" cried Klapaucius. "And where are the gruncheons? Where my dear, favorite pritons? Where now the gentle zits?!" "They no longer are, nor ever will exist again," the machine said calmly. "I executed, or rather only began to execute, your order..." "I tell you to do Nothing, and you... you..." "Klapaucius, don't pretend to be a greater idiot than you are," said the machine. "Had I made Nothing outright, in one fell swoop, everything would have ceased to exist, and that includes Trurl, the sky, the Universe, and you - and even myself. In which case who could say and to whom could it be said that the order was carried out and I am an efficient and capable machine? And if no one could say it to no one, in what way then could I, who also would not be, be vindicated?" "Yes, fine, let's drop the subject," said Klapaucius. "I have nothing more to ask of you, only please, dear machine, please return the zits, for without them life loses all its charm..." "But I can't, they're in z," said the machine. "Of course, I can restore nonsense, narrowmindedness, nausea, neerophilia, neuralgia, nefariousness and noxiousness. As for the other letters, however, I can't help you." "I want my zits!" bellowed Klapaucius.Klapaucius "Sorry, no zits," laid the machine. "Take a good look at this world, how riddled it is with huge, gaping holes, how full of Nothingness, the Nothingness that fills the bottomless void between the stars, how everything about us has become lined with it, how it darkly lurks behind each shred of matter. This is your work, envious one! And I hardly think the future generations will bless you for it . . ." "Perhaps... they won't find out, perhaps they won't notice," groaned the pale Klapaucius, gazing up incredulously at the black emptiness of space and not daring to look his colleague, Trurl, in the eve. Leaving him beside the machine that could do everything in n. Klapaucius skulked Home - and to this day the world has remained honeycombed with nothingness, exactly as it was when halted in the course of its liquidation. And as all subsequent attempts to build a machine on any other letter met with failure, it is to be feared that never again will we have such marvelous phenomena as the worches and the zits - no, never again.

|

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Jan 28, 2008 21:49:54 GMT 1

Why is Life on Earth Impossible?

A fragment of THE TWENTY-SECOND VOYAGE from The Star Diaries

This was a great day for the Andrygonians; in all the schools final examinations were just now being held. One of the government representatives inquired if I would care to honor the proceedings with my presence. Since I had been received with exceptional hospitality, I could hardly refuse this request. So then, straight from the airport we went by wurbil (large, legless amphibians, similar to snakes, widely used for transportation) to the city. Having presented me to the assembled youths and to the instructors as an eminent guest from the planet Earth, the government representative left the hall forthwith. The instructors had me sit at the head of the plystrum (a kind of table), whereupon the examination in progress was resumed. A Wurbil The pupils, excited by my presence, stammered at first and were extremely shy, but I reassured them with a cheerful smile, and when I whispered the right word now to this one, now to that, the ice was quickly broken. They answered better and better towards the end. At one point there came before the examining board a young Andrygonian, overgrown with ruddocks (a kind of oyster, used for clothing), the loveliest I had seen in quite some time, and he began to answer the questions with uncommon eloquence and poise. I listened with pleasure, observing that the level of science here was high indeed.

Then the examiner asked:

"Can the candidate for graduation demonstrate why life on Earth is impossible?"

With a little bow the youth commenced to give an exhaustive and logically constructed argument, in which he proved irrefutably that the greater part of Earth is covered with cold, exceedingly deep waters, whose temperature is kept near zero by constantly floating mountains of ice; that not only the poles, but the surrounding areas as well are a place of perpetual, bitter frost and that for half a year there night reigns uninterrupted. That, as one can clearly see through astronomical instruments, the land masses, even in the more temperate zones, are covered for many months each year by frozen water vapor known as "snow," which lies in a thick layer upon both hills and valleys. That the great Moon of Earth causes high tides and low, which have a destructive, erosive effect. That with the aid of the most powerful spyglasses one can see how very often large patches of the planet are plunged in shadow, produced by an envelope of clouds. That in the atmosphere fierce cyclones, typhoons and storms abound. All of which, taken together, completely rules out the possibility of the existence of life in any form. And if concluded the young Andrygonian in a ringing voice-beings of some sort were ever to try landing on Earth, they would suffer certain death, being crushed by the tremendous pressure of its atmosphere, which at sea level equals one kilogram per square centimeter, or 760 millimeters in a column of mercury.

This thorough reply met with the general approval of the board. Overcome with astonishment, I sat for the longest while without stirring and it was only when the examiner had proceeded to the next question that I exclaimed:

"Forgive me, worthy Andrygonians, but : ... well, it is precisely from Earth that I come; surely you do not doubt that I am alive, and you heard how I was introduced to you ..."

An awkward silence followed. The instructors were deeply offended by my tactless remark and barely contained themselves; the young people, who are not as able to hide their feelings as adults, regarded me with unconcealed hostility. Finally the examiner said coldly:

"By your leave, sir stranger, but are you not placing too great demands upon our hospitality? Are you not content with your most royal reception, with the fanfares, the tokens of esteem? Have we not done enough by admitting you to the High Plystrum of Graduation, is this still insufficient and you wish us in addition to change, entirely for you, the school program?1"

"But ... but Earth is in fact inhabited ..." I muttered, embarrassed.

"If such were the case," the examiner said, looking at me as if I were transparent, "that would constitute an anomaly of nature."

|

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Jan 28, 2008 21:51:00 GMT 1

Christianization of the Cosmos?

A fragment of THE TWENTY-SECOND VOYAGE from The Star Diaries

I was about to turn back into the vastness of space when I caught sight of a tiny figure gesturing to me from below. Shutting off the engine, I quickly glided down and brought the vehicle to rest near a group of picturesque cliffs, on which there rose a sizable building made of stone. Running across a field to meet me came a stalwart old man in the white frock of a Dominican monk. This was, as it turned out, Father Lacymon, the superior of all the missions active throughout the neighboring constellations within a radius of six hundred light-years. This region numbers roughly five million planets, of which two million four hundred thousand are inhabited. Father Lacymon, upon learning what had brought me to 'these parts, expressed his sympathy, but also his delight at my arrival, since, as he told me, I was the first man he had seen in seven months.An Octabod

"So accustomed have I become," he said, "to the ways of the Meodracytes, who live on this planet, that I constantly catch myself making this particular mistake: when I wish to listen care fully, I lift my hands thus, as they do . . ." (The Meodracytes, as everyone knows, have their ears beneath their arms.)

Father Lacymon proved to be a gracious host; together we sat down to a meal made up of local dishes (stuffed booch, loffles in gnussard, morchmell mumbo, and for dessert pidgies-the best I had had in quite some time), after which we retired to the veranda of the mission. The lilac sun warmed us, the pterodactyls, with which the planet teemed, sang in the bushes, and in the stillness of the afternoon the venerable prior of the Dominicans began to tell me of his troubles; he complained of the difficulties faced by missionary work in that area. The Quinquenemarians, for example, the inhabitants of torrid Antelena, who freeze at 600 degrees Celsius, don't even want to hear of Heaven, whereas descriptions of Hell awake in them a lively interest, and this because of the favorable conditions that obtain there (bubbling tar, flames). Moreover it is unclear which of them may enter the priesthood, for they have five separate sexes-not an easy problem for the theologians.

I expressed my sympathy. Father Lacymon shrugged: "That is not the half of it. The Whds, for instance, consider rising from the dead an act as commonplace as putting on one's clothes, and absolutely refuse to accept the phenomenon as a miracle. The Sassids of Egillia, they have no arms or legs; they could cross themselves with their tails, but I cannot make any decision on this myself; I'm waiting for an answer from the Apostolic See-it's been two years now and still the Vatican says nothing . . . And did you hear of the sad fate that befell poor Father Oribazy of our mission?"

I shook my head.

"Listen then, and I will tell you. Even the first discoverers of Ophoptopha could not find praises enough for its inhabitants, the mighty Gnelts. The consensus is that these intelligent beings are among the most obliging, kind, peaceable and altruistically inclined creatures in the entire Universe. Thinking therefore that such soil would be ideal to plant the seed of the faith, we sent Father Oribazy to the Gnelts, naming him bishop żn partibus infidelium. Arriving at Ophoptopha, he was received in such a way, that one could hardly ask for more: they lavished on him motherly solicitude, respect, hung on his every word, read the expressions of his face and instantly carried out his least request, they drank in the sermons he delivered, in short, they submitted to him completely. In the letters he wrote to me he could not find words enough to praise them, unfortunate man . . ."

Here the Dominican priest wiped a tear from his eye with the sleeve of his frock.

"In this propitious atmosphere Father Oribazy, never flagging, preached the tenets of the faith both day and night. He related to the Gnelts the history of the Old and New Testaments, the Apocalypse and the Epistles, then passed to the lives of the saints; he put particular fervor into the exalting of the Lord's martyrs. Poor man . . . that had always been his weakness ..."

Mastering his emotions, Father Lacymon continued in a trembling voice:

"And so he spoke to them of Saint John, who attained everlasting glory when they boiled him alive in oil, and of Saint Agnes, w ho let her head be severed for the faith, and of Saint Sebastian, pierced with many arrows and suffering grievous torments, for which he was greeted in Heaven by angels singing, and of the infant saints quartered, smothered, broken on the wheel and roasted over a slow fire. All these agonies they accepted with joy, secure in the knowledge that they were thereby winning for themselves a place at the right hand of the Lord of Hosts. And as he told them many similar lives, all worthy of emulation, the Gnelts, listening intently to his words, began to exchange significant looks, and the largest among them timidly spoke up:

"O reverend priest of ours, teacher and venerable father, tell us please, if you would but deign to lower yourself to your most lowly servants, does the soul of anyone willing to be martyred enter Heaven?"

"Assuredly so, my son!", replied Father Oribazy.

"Yes? That is very good . . . - said the Gnelt slowly. -And you, O father confessor, do you too wish to enter Heaven? To enter Heaven is my fondest hope, my son."

"And to become a saint? - the large Gnelt asked further. -O worthy son, who is there who would not wish to become one, but such high honor is hardly for the likes of a sinner like myself; one must put forth all one's strength and strive unceasingly and in the greatest humility, if one would enter on that path . . ."

"Then you do wish to be a saint? - repeated the Gnelt to make sure, casting an affirmative look at his comrades, who inconspicuously rose from their seats."

"Naturally, my son."

Well, then we will help you!"

"And how will you do that, dear lambs? - asked Father Oribazy with a smile, for he was gladdened by the simple zeal of his faithful flock."

In answer the Gnelts gently but firmly took him by the arms and said:

"In the way, dear Father, that you have just now taught us". Whereupon they pulled the skin from his back and rubbed the place with tar, as the executioner of'Ireland did to Saint Hyacinth, then they chopped off his left leg, as the heathens did to Saint Pafnuce, after which they ripped open his stomach and put inside a clump of straw, as it happened to the blessed Elizabeth of Normandy, and next they impaled him, as the Emalkites Saint Hugo, and broke his ribs, as the Tyracusans Saint Henry of Padua, and roasted him over a slow fire, as the Burgundians the Maid of Orleans. Then finally they stepped back, washed their hands and began shedding bitter tears for their lost shepherd. This was precisely how I found them, for in making the rounds of all the stars in my diocese I dropped in on their parish. When I heard what had transpired, my hair stood on end. Wringing my hands, I cried:

"Shameless criminals! Hell itself is not enough for youl Are you aware that you have damned your souls for all eternity?"

"Yes - they sobbed - we are aware of this!"

"That largest Gnelt rose up and spoke to me thus:

"Reverend Father, we are well aware that we shall all be damned and tormented till the end of time, and we had to struggle mightily in our hearts before we took this resolve, but Father Oribazy told us repeatedly that there was nothing a good Christian would not do for his neighbor, that one should give up everything for him and be prepared to make any sacrifice; and so with the greatest despair we relinquished our salvation, thinking only of our dear Father Oribazy, that he would gain a martyr's crown and sainthood. I cannot tell you how difficult this was for us, for before Father Oribazy's arrival here not one of us would have harmed a flea. Therefore we renewed our entreaties, we begged him on our knees to ease, to reduce a little the severity of the faith's commands, but he categorically maintained that for one's fellow man one should do everything, without exception. We were no longer able, then, to deny him. We reasoned, moreover, that we were beings of little significance and worth beside this pious man, that he deserved the greatest self-denial on our part. Also we fervently believe that our act was successful and that Father Oribazy now dwells in Heaven. Here you have, reverend Father, the sack with the money we collected for the canonization proceedings, as is required, Father Oribazy explained all that to us when asked. I must say that we used only his favorite tortures, those that he expounded to us with the most enthusiasm. We assumed that they would please him, and yet he resisted, in particular he disliked swallowing the molten lead. However we refused even to consider the possibility that that priest would tell us one thing and think another. The scream he uttered was only proof of the discontent of the lower, physical parts of his person and we ignored it, in keeping with the teaching that one must mortify the flesh so that the spirit may soar higher. To sustain him, we reminded him of the principles he had preached to us, to which Father Oribazy answered with but a single word, a word totally obscure and incomprehensible; we have no idea what it might mean, for we found it neither in the prayerbooks he had given us, nor in the Holy Scriptures."

|

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Jan 28, 2008 21:53:00 GMT 1

I liked all his books except one: The Investigation. It was too scary for a young boy like me - about dead bodies behaving like zombies.

The Investigation

(a fragment)

Rattling rhythmically at each floor, the old-fashioned elevator moved upward past glass doors decorated with etchings of flowers. It stopped. (...) The doors swung open.

"This way, gentlemen," gestured someone standing just inside.

Gregory was the last one in, right behind the doctor. Compared to the brightly lit corridor, the room was almost dark. Through the window the bare branches of a tree were visible in the fog outside. (...)

"Gentlemen," the Chief Inspector said (...) "I want you to go over every aspect of this case. Since the official record has been my only source of information, I think we should start with a brief summary. Farquart, perhaps you can begin." (...)

Farquart straightened up in his chair.

"The affair began around the middle of last November, but there may have been some earlier incidents that were ignored at the time. The first report to the police was made three days before Christmas, but an investigation in January showed that these corpse incidents began much earlier. The report was made in the town of Engender, and it was, strictly speaking, semiofficial in character. Plays, the local undertaker, complained to the commander of the district police station, who happens to be his brother-in-law, that someone was moving the bodies around during the night."

"What exactly did this moving consist of?" The Chief Inspector was methodically cleaning his glasses.

"The bodies were left in one position in the evening and found in different positions the following morning. (...) The undertaker isn't completely sure anymore whether the body involved was actually the drowned man's. In fact the whole report is somewhat irregular. Gibson, the Engender police commander, decided not to log any of this. (...) The second report was made in Planting, eight days after the first. Someone moving corpses at night in the cemetery mortuary again. The dead man was a stevedore named Thicker-he died after a long illness that almost bankrupted his family."

Farquart glanced out of the corner of his eye at Gregory, who was shifting around impatiently.

"The funeral was scheduled for the morning. When the family showed up at the mortuary they noticed that the body was lying face downward-that is, the back was facing upward - and that its hands were open, which gave them the impression that Thicker . . . had come back to life. At least that's what the family believed. Before long, rumors about some kind of trance were circulating in the neighborhood; people said that Thicker had only seemed to be dead, then woke up, found himself in a coffin, and died of fright, this time for good.

"The whole story was nonsense," Farquart continued. "A local doctor had certified Thicker's death beyond any shadow of a doubt. But as the rumors spread through the surrounding area, attention was drawn to the fact that people had been talking for some time about so-called moving corpses that changed position during the night."

"What does 'for some time' mean?" asked the Chief Inspector.

"There's no way of knowing. The rumors referred to incidents in Shaltam and Dipper. At the beginning of January the local forces made a cursory investigation, but they didn't take the matter too seriously, so they weren't very systematic. The evidence given by the local people was partly prejudiced, partly inconsistent, and as a result the investigation was worthless. In Shaltam it involved the body of one Samuel Filthey, dead of a heart attack. According to the gravedigger, who happens to be the town drunk, Filthey is supposed to have 'turned over in the coffin' on Christmas night. No one can substantiate the story. The incident in Dipper involved the body of an insane woman that was found in the morning on the floor next to the coffin. According to the neighbors, the woman's stepdaughter, who hated her, slipped into the funeral home during the night and threw her out of her coffin. The truth is, there are so many stories and rumors that it's impossible to get your bearings. It all boils down to one person giving you the name of an alleged eyewitness, and the `witness' sending you to someone else, and so on...

"The case would have been dropped as a sure ad acta," Farquart began speaking faster, "but on January sixteenth the corpse of one James Trayle disappeared from the mortuary in Treakhill. Sergeant Peel, on detail from our C.I.D., investigated the incident. The corpse was removed from the mortuary sometime between midnight and five in the morning, when the undertaker discovered that it was missing. The deceased was a male... The cause of death was poisoning by illuminating gas. It was an unfortunate accident."

"Autopsy?" said the Chief Inspector, raising his eyebrows. (...)

"There was no autopsy, but we're convinced it was an accident. Six days later, on January twenty-third, there was another incident, this time in Spittoon. The missing body belonged to one John Stevens, a twenty-eight-year-old laborer in a distillery. He died the day before, after inhaling poisonous fumes while cleaning one of the vats. The body was taken to the mortuary around three in the afternoon. The caretaker saw it for the last time around nine in the evening. In the morning it wasn't there. Sergeant Peel looked into this incident also, but nothing came of this investigation either, mainly because at the time we still hadn't thought of linking these two incidents with the earlier ones...(...) The third incident took place within the limits of Greater London in Lovering, where the Medical School has its new dissecting laboratory," Farquart continued in a dull voice, as if he had lost all interest in going on with his lengthy story. "The body of one Stewart Aloney disappeared; he was fifty years old, dead of a chronic tropical disease contracted while he was a sailor on the Bangkok run. This incident took place nine days after the other disappearances, on February second. (...) After this one the Yard took over. The investigation was conducted by Lieutenant Gregory, who later took command of one more case: the disappearance of a corpse from the mortuary of a suburban cemetery in Bromley on February twelfth-the incident involved the body of a woman who died after a cancer operation."(...)

"Lieutenant, tell us about your investigation."

Gregory cleared his throat, took a deep breath, and, flicking an ash into the ashtray, spoke in an unexpectedly quiet voice.

"I don't have much to brag about. All the corpses disappeared at night, there was no evidence on the scene, no signs of forcible entry. Besides, forcible entry wouldn't have been necessary since mortuaries aren't usually locked, and those that are could probably be opened with a bent nail by a child. (...) There was an unlocked window in the room from which the corpse disappeared-in fact, it was open, as if someone had gone out through it."

"He had to get in first," Sorensen interrupted impatiently.

"A brilliant observation," Gregory replied, then regretted his words and peeked at the Chief, who remained silent, unmoving, as if he hadn't heard anything.

"The laboratory is on the first floor," the lieutenant continued after an awkward silence. "According to the janitor, the window was locked along with all the others. He swears that all the windows were locked that night-says he's absolutely certain because he checked them himself. The frost was setting in and he was afraid the radiators would freeze if the windows were open. Like most dissecting labs, they hardly give enough heat as it is." (...)

"Are there any possible hiding places in the laboratory?" the Chief Inspector asked. (...)

"Well, that . . . would be out of the question, Chief Inspector. No one would be able to hide without the janitor's help. There's no furniture except for the dissecting tables, no dark corners or alcoves... in fact, nothing at all except a few closets for the students' coats and equipment, and even a child couldn't fit into any of them."

"Do you mean that literally?"

"Sir?"

"That they're too small for a child," the Chief Inspector said quietly.

"Well..." The lieutenant wrinkled his brow. "A child might manage to squeeze into one, but at best only a seven or eight-year-old."

"Did you measure the closets?"

"Yes." The answer was uttered without hesitation. (...) "They all turned out to be the same size. Aside from the closets, there are some toilets, washrooms, and classrooms; a refrigerator and a storeroom in the basement; the professor's office and some teachers' rooms upstairs. Harvey says that the janitor checks each of the rooms every night, sometimes more than once - in my opinion, he tends to overdo it. Anyway, no one could have managed to hide there." (...)

"Are you finished?"

"Yes sir. (...) At least as far as these three incidents are concerned. In the last case, though, I looked over the surrounding area very carefully - I was particularly interested in any unusual activity near the lab that night. The constables on duty in the neighborhood hadn't noticed anything suspicious. Also, when I took over the case I tried to find out as much as I could about the earlier incidents; I talked to Sergeant Peel and I went to all the other places but I didn't find a thing, not one piece of evidence of any kind. Nothing, absolutely nothing. The woman who died of cancer and the laborer both disappeared in similar circumstances. In the morning, when someone from the family arrived at the mortuary, the coffin was empty."

|

|

livia

Just born

Posts: 121

|

Post by livia on Feb 18, 2008 13:16:00 GMT 1

I liked all his books except one: The Investigation. It was too scary for a young boy like me - about dead bodies behaving like zombies. Yes, Bonobo, you are only a man and you can be excused ;D ;D ;D I did like Śledztwo and Katar - I read an edition where these are in one book. Of course I was scared to death but there was a period when I enjoyed being scared. I greatly enjoyed Lem's Powrót z gwiazd. And while talking SF I have to mention John Wyndham and his "Day of the Tryfids". I was scared and amazed simultaneously! |

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Feb 18, 2008 23:46:08 GMT 1

I liked all his books except one: The Investigation. It was too scary for a young boy like me - about dead bodies behaving like zombies. Yes, Bonobo, you are only a man and you can be excused ;D ;D ;D I did like Śledztwo and Katar - I read an edition where these are in one book. Of course I was scared to death but there was a period when I enjoyed being scared. I greatly enjoyed Lem's Powrót z gwiazd. And while talking SF I have to mention John Wyndham and his "Day of the Tryfids". I was scared and amazed simultaneously! It is funny, I have just reread Powrót z Gwiazd for the twentieth time in my life. It is naive at times but very appealing with its warmth. Something like the French film Amelia- sweetly moving. I also read Katar, and I had those two in one book, too. I think we had the same edition. It had hard black covers. As for Investigation, I read it as a really young boy, about 10, when I was on holidays, left alone by parents, in a countryside house, staying in a room in the attic, dark and creaking. You can imagine how I felt at night, I couldn`t sleep at all. I don`t know Wyndham but I know brothers Strugacki and their famous Picnic on the side of the Road, made into the movie Stalker. |

|

livia

Just born

Posts: 121

|

Post by livia on Feb 19, 2008 9:59:05 GMT 1

There was a film "Day of the Trifids" based on the book. I was lucky to read the book before I watched the film. The book is as almost always so much better and the film is a spoiler of the book. In the deeper layer in some way it resembles another favourites of mine - "Blindness' (Miasto Ślepców) by Jose Saramago.

Ayyy, I too read Powrót z gwiazd many times! Virtually every time I was sick ;D ;D ;D

|

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Feb 22, 2008 21:48:06 GMT 1

There was a film "Day of the Trifids" based on the book. I was lucky to read the book before I watched the film. The book is as almost always so much better and the film is a spoiler of the book. In the deeper layer in some way it resembles another favourites of mine - "Blindness' (Miasto Ślepców) by Jose Saramago. Ayyy, I too read Powrót z gwiazd many times! Virtually every time I was sick ;D ;D ;D I have read a few Western sci-fiction authors but, frankly speaking, I didn`t appreciate them too much. The Slavic nature of Lem or Strugacki brothers appeals to me much better. And their humour, too. Recently I tried to read Hothouse (Cieplarnia) by Brian Aldiss, a book published in 1962 and considered classic. My wife borrowed it from the library and read whole. I didn`t. It was so naively uninteresting that I read a dozen pages and the ending and put it away. |

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Feb 22, 2008 21:50:51 GMT 1

Tale of The Computer That Fought a Dragon

King Poleander Partobon, ruler of Cyberia, was a great warrior, and being an advocate of the methods of modern strategy, above all else he prized cybernetics as a military art. His kingdom swarmed with thinking machines, for Poleander put them everywhere he could. (...) On the planet cyberbosks of cybergorse rustled in the wind, cybercalliopes and cyberviols sang - but besides these civilian devices there were twice as many military, for the King was most bellicose. (...) There was only this one problem, and it troubled him greatly, namely, that he had not a single adversary or enemy and no one in any way wished to invade his land, and thereby provide him with the opportunity to demonstrate his kingly and terrifying courage. (...) In the absence of genuine enemies and aggressors the King had his engineers build artificial ones, and against these he did battle, and always won. However (...) the subjects murmured when all too many cyberfoes had destroyed their settlements and towns (...) and the King wearied of the war games on the planet (...) decided to raise his sights. Now it was cosmic wars and sallies that he dreamed of.

(...) And so the royal engineers built on the Moon a splendid computer, which in turn was to create all manner of troops and self-firing gunnery. The King lost no time in testing the machine's prowess this way and that; at one point he ordered it - by telegraph - to execute a volt-vault electrosault: for he wanted to see if it was true, what his engineers had told him, that that machine could do anything. If can do anything, he thought, then let it do a flip. However the text of the telegram underwent a slight distortion and the machine received the order that it was to execute not an electrosault, but an electrosaur - and this it carried out as best it could.

Meanwhile the King conducted one more campaign, liberating some provinces of his realm seized by cyberknechts; he completely forgot about the order given the computer on the Moon, then suddenly giant boulders came hurtling down from there. (...) Fuming, he telegraphed the Moon computer at once, demanding an explanation. It didn't reply however, for it no longer was: the electrosaur had swallowed it and made it into its own tail.

Immediately the King dispatched an entire armed expedition to the Moon (...) to slay the dragon, but there was only some flashing, some rumbling, and then no more computer nor expedition; for the electrodragon wasn't pretend and wasn't pretending (...) and had moreover the worst of intentions regarding the kingdom and the King. (...)

The King thought and thought, but he saw no remedy. (...) To send machines was no good, for they would be lost, and to go himself was no better, for he was afraid. Suddenly the King heard, in the stillness of the night, the telegraph chattering from his royal bedchamber. (...) The King jumped up and ran to it, the apparatus meanwhile went tap-tap, tap-tap, and tapped out this telegram: THE DRAGON SAYS POLEANDER PARTOBON BETTER CLEAR OUT BECAUSE HE THE DRAGON INTENDS TO OCCUPY THE THRONE!

The King (...) ran down to the palace vaults, where stood the strategy machine, old and very wise. (...) He had not as yet consulted it, since prior to the rise and uprise of the electrodragon they had argued on the subject of a certain military operation; but now was not the time to think of that - his throne, his life was at stake!

He plugged it in, and as soon as it warmed up he cried:

"My old computer! My good computer! It's this way and that, the dragon wishes to deprive me of my throne; to cast me out, help, speak, how can I defeat it?!"

"Uh-uh," said the computer. "First you must admit I was right in that previous business, and secondly, I would have you address me only as Digital Grand Vizier, though you may also say to me: 'Your Ferromagneticity'!"

"Good, good, I'll name you Grand Vizier, I'll agree to anything you like, only save me!"

The machine whirred, chirred, hummed, hemmed, then said:

"It is a simple matter. We build an electrosaur more powerful than the one located on the Moon. It will defeat the lunar one, settle its circuitry once and for all and thereby attain the goal!""

"Perfect!" replied the King. "And can you make a blueprint of this dragon?"

"It will be an ultradragon," said the computer. "And I can make you not only a blueprint, but the thing itself, which I shall now do, it won't take a minute, King!" And true to its word, it hissed, it chugged, it whistled and buzzed, assembling something down within itself, and already an object like a giant claw, sparking, arcing, was emerging from its side, when the King shouted:

"Old computer! Stop!"

"Is this how you address me? I am the Digital Grand Vizier!"

"Ah, of course," said the King. "Your Ferromagneticity, the electrodragon you are making will defeat the other dragon, granted, but it will surely remain in the other's place, how then are we to get rid of it in turn?!"

"By making yet another, still more powerful," explained the computer.

"No, no! In that case don't do anything, I beg you, what good will it be to have more and more terrible dragons on the Moon when I don't want any there at all?"

"Ah, now that's a different matter," the computer replied. "Why didn't you say so in the first place? You see how illogically you express yourself? One moment ... I must think." (...)

It hummed, it huffed, and it said:

"We create a general theory of the slaying of electrodragons, of which the lunar dragon will be a special case, its solution trivial."

"Well, create such a theory!" said the King.

"To do this I must first create various experimental dragons."

"Certainly not! No thank you!" exclaimed the King. "A dragon wants to deprive me of my throne, just think what might happen if you produced a swarm of them!"

"Oh? Well then (...) we will use a strategic variant of the method of successive approximations. Go and telegraph the dragon that you will give it the throne on the condition that it perform three mathematical operations, really quite simple..."

The King went and telegraphed, and the dragon agreed. (...)

"Now," said the computer, "here is the first operation: tell it to divide itself by itself!"

The King did this. The electrosaur divided itself by itself, but since one electrosaur over one electrosaur is one, it remained on the Moon and nothing changed.

Is this the best you can do?!" cried the King, running into the vault with such haste, that his slippers fell off. (...) "Nothing changed!"

"(...) The operation was to divert attention," said the computer. "And now tell it to extract its root!" The King telegraphed to the Moon, and the dragon began to pull, push, pull, push, until it crackled from the strain, panted, trembled all over, but suddenly something gave - and it extracted its own root! The King went back to the computer.

"The dragon (...) extracted the root and threatens me still!" he shouted from the doorway. "What now, my old ... I mean, Your Ferromagneticity?!"

"Be of stout heart," it said. "Now go tell it to subtract itself from itself!"

The King hurried to his royal bedchamber, sent the telegram, and the dragon began to subtract itself from itself, taking away its tail first, then legs, then trunk, and finally, when it saw that something wasn't right, it hesitated, but from its own momentum the subtracting continued, it took away its head and became zero, in other words nothing: the electrosaur was no more!

"The electrosaur is no more," cried the joyful King, bursting into the vault. "Thank you, old computer ... many thanks ... you have worked hard ... you have earned a rest, so now I will disconnect you."

"Not so fast, my dear," the computer replied. "I do the job and you want to disconnect me, and you no longer call me Your Ferromagneticity?! That's not nice, not nice at all! Now I myself will change into an electrosaur, yes, and drive you from the kingdom, and most certainly rule better than you, for you always consulted me in all the more important matters, therefore it was really I who ruled all along, and not you.

And huffing, puffing, it began to change into an electrosaur; flaming electroclaws were already protruding from its sides when the King, breathless with fright, tore the slippers off his feet, rushed up to it and with the slippers began beating blindly at its tubes! The computer chugged, choked, and got muddled in its program - instead of the word "electrosaur" it read "electrosauce," and before the King's very eyes the computer, wheezing more and more softly, turned into an enormous, gleaming-golden heap of electrosauce, which, still sizzling, emitted all its charge in deep-blue sparks, leaving Poleander to stare dumbstruck at only a great, steaming pool of gravy...

With a sigh the King put on his slippers and returned to the royal bedchamber. However from that time on he was an altogether different king: the events he had undergone made his nature less bellicose, and to the end of his days he engaged exclusively in civilian cybernetics, and left the military kind strictly alone.

|

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Apr 21, 2010 20:03:31 GMT 1

Lem and Stanko in London

27.03.2010 13:10

A screen adaptation of a short story by the famous Polish science fiction writer Stanislaw Lem (1921-2006) is premiered tonight at the Barbican Cinema in London.

‘The Mask’ is the work of Timothy and Stephen Quay. The soundtrack is by the Polish composer Krzysztof Penderecki.

The Quay Brothers have also designed the cover to a bilinqual edition of a selection of short stories and essays by Polish and British authors inspired by the writings of Stanisław Lem. The book, entitled ‘Lemistry/Lemiskalia’, is to be published in London by NewCon Press. The production of the film and the publication of the book have been supported by the Polish Cultural Institute in London.

The premiere of ‘The Mask’ will be followed by a concert by the internationally renowned Polish jazz trumpeter Tomasz Stańko with Adam Pieronczyk (saxophones), Dominik Wania (piano), Sławomir Kurkiewicz (bass) and Olavi Louhivuori (drums). The event is in tribute to the jazz pianist and composer Krzysztof Komeda, who died prematurely in 1969, aged 38. Komeda and Stańko were key personalities in the evolution of the Polish jazz scene in the 1960s.

|

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Oct 1, 2010 20:48:19 GMT 1

Stanislaw Lem leads Polish satellite poll

30.09.2010 13:40

The late science fiction author Stanisław Lem is favourite to have the first Polish satellite named after him.

Lem’s name currently tops the list in an internet poll launched on the Education Ministry web site. The vote closes at midnight tonight and the results are to be announced on October 7.

So far close to 45 percent of more than 45,000 votes cast on the webpage indicate Stanisław Lem, who died in 2006, a clear leader. In second place is space travel pioneer Ary Sternfeld, born in Sieradz, and third is 17th century Gdańsk astronomer Jan Hevelius.

The first Polish satellite will be placed in orbit in 2011 and a second in 2013.

Both are being built by the Space Research Centre of the Polish Academy of Sciences with the Copernicus Astronomy Centre in Toruń, in cooperation with space research institutes in Vienna, Graz, Toronto and Montreal.

The launch will be made from the Sriharikota spaceport in India.

The satellites are part of the international BRITE project (Bright Target Explorer Constellation), a programme carrying out continuous observation of 286 brightest stars in the sky.

The cost of the project is 14.2 million zloty (more than 3.5 million euro), Poland’s biggest outlay to astronomy and space research since 1986.

Voting for the patron of the first Polish satellite is possible here. You will be asked to type in letters into an anti-spam box before being directed to the voting area.

|

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Apr 3, 2011 16:18:57 GMT 1

La Dolce Vita: Remembering Stanislaw Lem

28.03.2011 13:49

Sunday saw the fifth anniversary of the passing of Stanislaw Lem, Poland's most translated writer.

The author, who invigorated the world of science fiction, yet remained dubious about most of the genres representatives, is best known for his books Solaris and The Cyberiad, the latter hailed as one of the wittiest Polish books of the twentieth century.

Those closest to Lem, who was born in Lwow (now Lviv, Ukraine) and resettled in Krakow after the war, remember him as a resoundingly original and amusing man.

His son Tomasz, who recently penned a well-received memoir, noted that the great writer was also something of a greedy fellow.

According to Lem junior, the writer had a private stash of sweets hidden in the garage, typically orange peel enrobed in chocolate. Whilst moving house, it turned out that these papers rose almost to the ceiling.

Such delicacies were often hard to come by during the communist years. A telling detail is that when the budding scribe proposed to his beloved in the fifties, he sent her an entire torte.

Lem remained original in death. His Krakow tomb, a concrete slab, seems drab from afar, set as it is amidst a sea of fancy marble concoctions.

However, on closer inspection, it emerges that the face of the tomb incorporates a swirl of red paint, giving the structure a decidedly planetary appearance, wholly fitting for a master of science fiction.

A Latin inscription reads 'feci, quod potui, faciant meliora potentes' (I did what I could, let those who can, do better').

An asteroid, 3836 Lem, has been named in tribute to the writer, likewise Poland's first satellite.

|

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on May 12, 2011 19:55:33 GMT 1

A few of his ideas from his books. Return from the Stars:www.technovelgy.com/ct/AuthorSpecAlphaList.asp?BkNum=283Betrization Calster - portable cash printer Crystal Corn - tiny crystal books Electronic Book Store Interactive Map - very early concept Lecton - be read to Opton - electronic book Parastatics Reciprocal Name - cellphone nickname Sky Ceiling - long before Hogwarts Spray-On Clothing - dresses in a can My favourite: Betrization

An in utero method of reducing human aggression.

Betrization acted on the developing prosencephalon at an early stage in life by means of a group of proteolytic enzymes. The effects were selective: the reduction of aggressive impulses by 80 to 88 percent in comparison with the nonbetrizated; the elimination of the formation of associative links between acts of aggression and the sphere of positive feelings; a general 87-percent reduction in the possibility of accepting personal risk in life.

Betrization causes the disappearance of aggression through the complete absence of command, and not by inhibition.

The Invincible Inorganic Evolution Metal Insects Nanomachine Swarm (Black Cloud) - tiny machines work together Repair Robots - helpful droids

Nanomachine Swarm (Black Cloud)

A cloud of tiny machines, able to work together autonomously.

A huge black cloud seems to attack an airship. The ship's sensors report that the cloud seems to be made of iron. How could such a thing exist?

"What is the nature of this cloud? What is your opinion?" he asked without any introductory remarks.

"It is made up of tiny metal particles. A remote-controlled emulsion, as it were, with uniform center," answered Jazon.

Further speculation is made upon the gathering of additional evidence.

"Two types of systems were successful in this evolutionary pattern: first, those that made the greatest progress in miniaturization and then those that became settled in a definite place. The first type were the beginning of these 'black clouds.' I believe them to be very tiny pseudo insects that, if necessary, and for their common good, can unite to form a superordinate system. This is the course taken by the evolution of the mobile mechanisms."

www.technovelgy.com/ct/AuthorSpecAlphaList.asp?BkNum=482

The Cyberiad: Fables for the Cybernetic Age Electronic Bard Femfatalatron Gigagnostotron Gnostotron Kingdom in a Box www.technovelgy.com/ct/AuthorSpecAlphaList.asp?BkNum=228

Kingdom in a Box

An entire civilization in miniature - in an interactive box.

Trurl takes pity on King Excelsius, exiled dictator, by creating for him a tiny kingdom all his own.

...all of this ... fit into a box ... just the size to be carried about with ease. This Trurl presented to Excelcius, to rule and have dominion over forever; but first he showed him where the input and output of his brand-new kingdom were, and how to program wars, quell rebellions, exact tribute, collect taxes ... and explained everything so well that the king, an old hand in the running of tyrannies, instantly grasped the directions and, without hesitation, while the constructor watched, issued a few trial proclamations, correctly manipulating the control knobs, which were carved with imperial eagles and regal lions.

|

|