Post by Bonobo on Jul 30, 2011 21:03:32 GMT 1

www.theguardian.com/news/datablog/2014/sep/25/comparing-the-minimum-wage-across-europe-using-the-price-of-a-big-mac

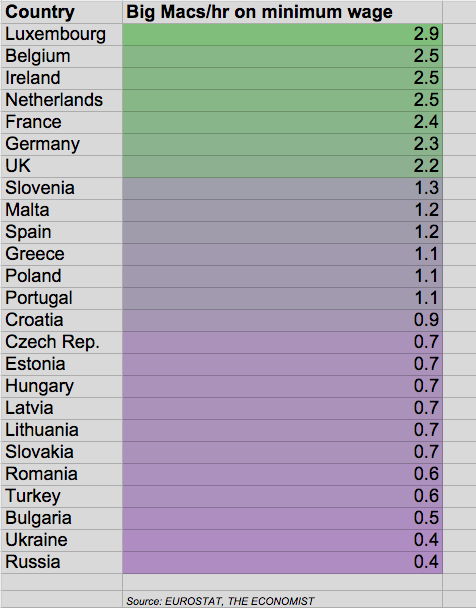

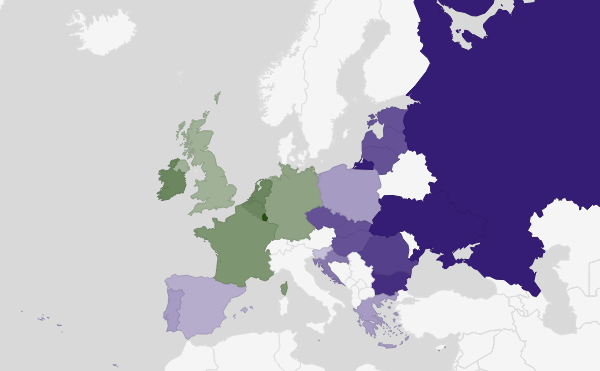

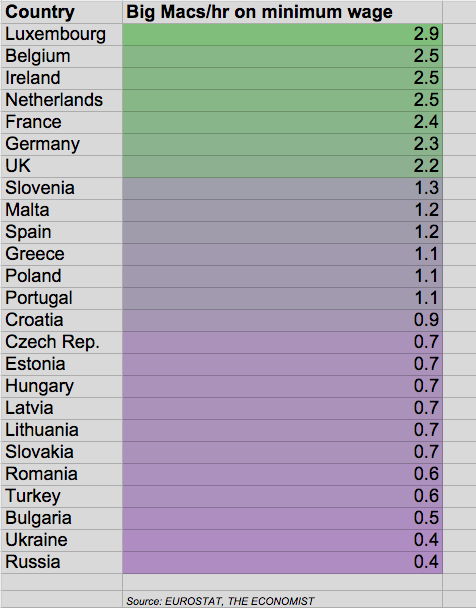

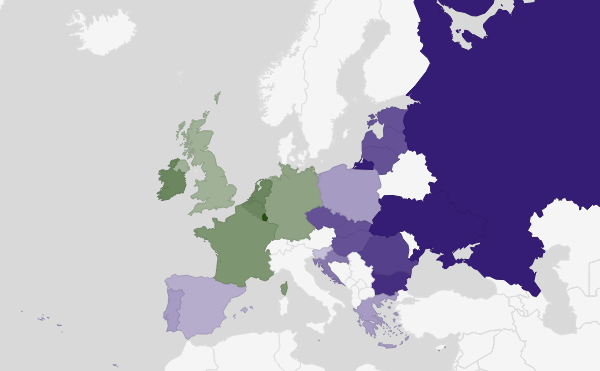

Poland right in the middle

The figures vary quite noticeably. Luxembourg’s minimum wage buys you just about three Big Macs in an hour, while most of northern Europe (and France) between 2-2.5 Big Macs. Moving south, the minimum wage nets about one Big Mac an hour. As we progress east, it begins to cost more than an hour of work on the minimum wage in order to afford a Big Mac. In Russia (excluding Moscow**), assuming one can still find a McDonald’s open, more than two hours work on the minimum 5,554 rubles wage would be needed to savour a Big Mac.

THE Big Mac index was invented by The Economist in 1986 as a lighthearted guide to whether currencies are at their “correct” level. It is based on the theory of purchasing-power parity (PPP), the notion that in the long run exchange rates should move towards the rate that would equalise the prices of an identical basket of goods and services (in this case, a burger) in any two countries. For example, the average price of a Big Mac in America in January 2017 was $5.06; in China it was only $2.83 at market exchange rates. So the "raw" Big Mac index says that the yuan was undervalued by 44% at that time.

Burgernomics was never intended as a precise gauge of currency misalignment, merely a tool to make exchange-rate theory more digestible. Yet the Big Mac index has become a global standard, included in several economic textbooks and the subject of at least 20 academic studies. For those who take their fast food more seriously, we have also calculated a gourmet version of the index.

This adjusted index addresses the criticism that you would expect average burger prices to be cheaper in poor countries than in rich ones because labour costs are lower. PPP signals where exchange rates should be heading in the long run, as a country like China gets richer, but it says little about today's equilibrium rate. The relationship between prices and GDP per person may be a better guide to the current fair value of a currency. The adjusted index uses the “line of best fit” between Big Mac prices and GDP per person for 48 countries (plus the euro area). The difference between the price predicted by the red line for each country, given its income per person, and its actual price gives a supersized measure of currency under- and over-valuation.

www.economist.com/content/big-mac-index

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Big_Mac_Index

Poland right in the middle

The figures vary quite noticeably. Luxembourg’s minimum wage buys you just about three Big Macs in an hour, while most of northern Europe (and France) between 2-2.5 Big Macs. Moving south, the minimum wage nets about one Big Mac an hour. As we progress east, it begins to cost more than an hour of work on the minimum wage in order to afford a Big Mac. In Russia (excluding Moscow**), assuming one can still find a McDonald’s open, more than two hours work on the minimum 5,554 rubles wage would be needed to savour a Big Mac.

THE Big Mac index was invented by The Economist in 1986 as a lighthearted guide to whether currencies are at their “correct” level. It is based on the theory of purchasing-power parity (PPP), the notion that in the long run exchange rates should move towards the rate that would equalise the prices of an identical basket of goods and services (in this case, a burger) in any two countries. For example, the average price of a Big Mac in America in January 2017 was $5.06; in China it was only $2.83 at market exchange rates. So the "raw" Big Mac index says that the yuan was undervalued by 44% at that time.

Burgernomics was never intended as a precise gauge of currency misalignment, merely a tool to make exchange-rate theory more digestible. Yet the Big Mac index has become a global standard, included in several economic textbooks and the subject of at least 20 academic studies. For those who take their fast food more seriously, we have also calculated a gourmet version of the index.

This adjusted index addresses the criticism that you would expect average burger prices to be cheaper in poor countries than in rich ones because labour costs are lower. PPP signals where exchange rates should be heading in the long run, as a country like China gets richer, but it says little about today's equilibrium rate. The relationship between prices and GDP per person may be a better guide to the current fair value of a currency. The adjusted index uses the “line of best fit” between Big Mac prices and GDP per person for 48 countries (plus the euro area). The difference between the price predicted by the red line for each country, given its income per person, and its actual price gives a supersized measure of currency under- and over-valuation.

www.economist.com/content/big-mac-index

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Big_Mac_Index