Mr. Fico, Slovak prime minister in office, recently said that Slovakia was established for Slovaks, not for minorities.

media.economist.com/sites/default/files/imagecache/full-width/images/2013/03/blogs/eastern-approaches/20130309_eup504.jpg Slovakia for Slovaks?

media.economist.com/sites/default/files/imagecache/full-width/images/2013/03/blogs/eastern-approaches/20130309_eup504.jpg Slovakia for Slovaks?Mar 7th 2013, 12:35 by B.C. | PRAGUE

Copyright © The Economist Newspaper Limited 2013.

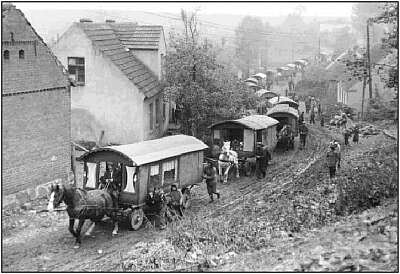

JUST 20 years into statehood, nationalism is a common feature of Slovak politics. Still, when Robert Fico (pictured above), the prime minister, said the country had been “established for Slovaks, not for minorities” in a recent speech, both the tenor and timing of the rhetoric raised eyebrows.

Mr Fico has backpedalled since the late-February address, insisting that his words were being misinterpreted. Still, more than a few observers have opined that the wording reeked of old-fashioned scapegoating as a means to distract from a 15% unemployment rate, the highest in nearly a decade. “The prime minister is so used to having a [parliamentary] majority that he has decided to flaunt his intolerance of minorities in the hope that it will hide his inability to manage the economic crisis and rising unemployment,” read a recent piece in SME, Slovakia’s most-influential daily.

Independent Slovakia’s founding narrative is one of overcoming foreign domination, first Hungarians and then Czechs – not to mention 20th century entanglements with Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union. Slovaks were ruled from Budapest for more than 900 years until the end of the first world war. About 9% of the population still consider themselves Hungarian, and whole towns and villages are predominantly Hungarian-speaking. Spats over the official language of public business, street signage and dual citizenship have been regular features of recent years. The apex of these tensions saw Slovakia deny the Hungarian president entry to the country in 2009, as he sought to celebrate a Hungarian holiday with a predominantly Hungarian village on Slovak territory.

The sweeping statements made by Mr Fico have drawn the ire of leaders of the homosexual and Roma communities as well. After a recent government proposal to create boarding schools for Roma children drew criticism, he sarcastically branded his critics “human-rights angels.” Such loose talk could possibly be dismissed if Mr Fico were not such a careful political tactician. Among other things, he was able to engineer the 2011 downfall of the previous centre-right government by first withholding, and then delivering votes from his Smer party on European Union measures to combat the economic crisis, which his party ideologically and officially supported. In the general election that followed Mr Fico’s left-leaning party took an outright majority of parliamentary seats.

Mr Fico has toyed with nationalism before. His previous government, a coalition that led the country from 2006 to 2010, included the Slovak National Party. Ján Slota, the leader of that party, is notable for a number of number of reasons, including a proposed Roma policy that involved "a small courtyard and with a long whip" and the pledge to “go with tanks and take Budapest down.” Mr Slota was also frequently spotted tooling around his native ®ilina in a Bentley (including by our correspondent), a somewhat unorthodox vehicle for a humble civil servant.

Previously guilty by association, Mr Fico’s recent brandishing of nationalist oratory is more worrying. Injected into an environment with 35% youth unemployment, it might make for an explosive mix

Slovakia has a troublesome past in the sense that both Fascism and Slovak Communism had a bad influence on the country and the Slovaks in my opinion.

Think about

the Slovak Republic (1939–1945), Jozef Tiso. Between 1939 and 1945, TJozef Tiso was the head of

the Slovak State,

a satellite state of Nazi Germany. After the end of World War II, Tiso was convicted and hanged for war crimes.

the Slovak RepublicThe Slovak Republic was an authoritarian state where the German pressure resulted in the adoption of many elements of German nacism. Some historians characterized the Slovak regime from 1939 to 1945 as clerical fascism. The government issued a number of antisemitic laws, prohibiting the Jews from participation in public life, and later supported their deportation to concentration camps erected by Germany on Polish territory. The leading political party was the Hlinka's Slovak People's Party. All other political parties were forbidden. One exception was the openly fascist party representing the Hungarian national minority, the previous Hungarians which continued its activities in Slovakia.

Jozef Tiso meets Adolf Hitler

Jozef Tiso meets Adolf Hitler 50 Slovak koruna silver coin issued for the fifth anniversary of the Slovak Republic (1939–1945) with an effigy of the slovak president Jozef Tiso.

50 Slovak koruna silver coin issued for the fifth anniversary of the Slovak Republic (1939–1945) with an effigy of the slovak president Jozef Tiso.The Czechoslovak region lay across the great ancient trade routes of Europe, and, by virtue of its position at the heart of the continent, it was a place where the most varied of traditions and influences encountered each other. The Czechs and the Slovaks traditionally shared many cultural and linguistic affinities, but they nonetheless developed distinct national identities. The emergence of separatist tendencies in the early 1990s, following the loosening of Soviet hegemony over eastern Europe, ultimately led to the breakup of the federation.

The part of Europe that constitutes the modern states of the Czech Republic and Slovakia was settled first by Celtic, then by Germanic, and finally by Slavic tribes over the course of several hundred years. The major political and historical regions that emerged in the area—Bohemia, Moravia, and Slovakia—coexisted, with a constantly changing degree of political interdependence, for more than a millennium before combining to form the modern state of Czechoslovakia in 1918. Each was subject to conquest; each underwent frequent shifts of population and periodic religious upheavals; and at times at least two of the three were governed by rival rulers. Bohemia and Moravia—the constituent regions of the Czech Republic—maintained close cultural and political ties and in fact were governed jointly during much of their history. Slovakia, however, which bordered on the Little Alfold (Little Hungarian Plain), was ruled by Hungary for almost 1,000 years and was known as Upper Hungary for much of the period before 1918. Thus, the division of Czechoslovakia at the end of 1992 was based on long-standing historical differences.

SlovakiaSlovakia was inhabited in the first centuries ce by Illyrian,

Celtic, and then

Germanic tribes.

The Slovaks—Slavs closely akin to, but possibly distinct from, the

Czechs—probably entered it from

Silesia in the

6th or

7th century. For a time they were subject to

the Avars, but in the

9th century the area between the

Morava River and the c

entral highlands formed part of

Great Moravia, when

the Slovak population accepted

Christianity from

Cyril and

Methodius. In the

890s, however, the

German king Arnulf called in

the Magyars (Hunagians) to help him against

Moravia. As

Slovakia lay in their path,

they overran it.

The Moravian state was destroyed in the first decade of the 10th century, and, after

a period of disorder in the 11th century,

Slovakia found itself

incorporated as

one of the lands of the Hungarian crown.

The main ethnic frontier between

Magyars (

Hungarians) and

Slovaks ran along the line where the foothills of the

Western Carpathians merge into the lowland plains. Nevertheless, the landlord class of

Slovakia was

Magyar, and much of the urban population was

German. (German settlers—

tradesmen,

craftsmen, and

miners—largely founded the towns in

Slovakia.) On the other hand, as the country suffered from chronic overpopulation, a constant stream of Slovak peasants moved down into the plains, where they usually were Magyarized in two or three generations.

In

Hungary (the Hungarian part of the Austria-Hungarian empire of which Slovakia was part of) the dominant

Hungarians systematically

suppressed Slovak ethnic identity. This was achieved primarily through a policy of

Magyarization, which made

the Hungarian language paramount in

administration,

education, and

business.

In the early 20th century (1990 - 1919), in the Hungarian portion of the empire of Austria-Hungary, the Slovaks continued to experience ever-increasing

Magyarization. By the end of the 19th century

no Slovak secondary schools remained. Linguistic oppression also extended to religion: in 1907 at Černová (now Stará Černová, Slvk.), some

15 Slovak demonstrators demanding that a new church be consecrated by the Slovak nationalist priest

Andrej Hlinka were shot by the police. In politics, only the

Social Democrats and the nationalistic

Slovak People’s Party, led by

Hlinka, took interest in

the Slovak people. Certain

Slovak intellectuals associated with the periodical

Hlas chose a

pro-Czech orientation in their

search for political allies. The percentage of

Slovaks in the region declined steadily. Many, in search of work, migrated to other parts of the empire. By

World War I about

half a million Slovaks had emigrated abroad, mostly to

the United States.

The end of Czechoslovakia and the emergence of SlovakiaThe Czechoslovak federation began to appear increasingly fragile in 1991–92, and separatism became a momentous issue. Parliamentary elections in June 1992 gave the Czech premiership to Václav Klaus, an economist by training and finance minister since 1989. Klaus headed a centre-right coalition that included the Civic Democratic Party, which he had cofounded. The Slovak premiership went to Vladimir Mečiar, a vocal Slovak nationalist and prominent member of Public Against Violence who had served briefly as Slovak prime minister in 1990–91. Mečiar headed his Movement for a Democratic Slovakia party. The parties led by Klaus and Mečiar were supported by about one-third of the electorate in their respective republics, but the differences between the two were so great that a lasting federal government could not be formed.

After Havel’s resignation on July 20, 1992, no suitable candidate for the federal presidency emerged; Czechoslovakia now lacked a symbol of unity as well as a convincing advocate. Thus, the assumption was readily made, at least in political circles, that the Czechoslovak state would have to be divided. There was little evidence of public enthusiasm for the split, but neither Klaus nor Mečiar wished to ask the population for a verdict through a referendum. The two republics proceeded with separation negotiations in an atmosphere of peace and cooperation. By late November, members of the National Assembly had voted Czechoslovakia out of existence. Both republics promulgated new constitutions, and at midnight on Dec. 31, 1992, after 74 years of joint existence disrupted only by World War II, Czechoslovakia was formally dissolved. With the completion of this so-called

Velvet Divorce, the independent countries of

Slovakia and the

Czech Republic were created on Jan. 1, 1993.

Vladimír Mečiar

Vladimír Mečiar (born 26 July 1942) who served three times as Prime Minister of Slovakia serving from 1990 to 1991, from 1992 to 1994, and from 1994 to 1998, was criticised by his opponents as well as by Western political organisations for having an autocratic style of administration.

After eight members of the parliament left Mečiar's

HZDS party in March 1993, Mečiar lost his parliamentary majority. At the same time the

HZDS also lost the support of the president,

Michal Kováč, who was originally nominated by the

HZDS. However, it was only in March 1994 that he was unseated as prime minister by the parliament (National Council of the Slovak Republic) and the opposition parties created a new government under Jozef Moravčík's lead. However, after the elections held at the turn of September and October 1994, in which his HZDS won 35% of the vote, he became prime minister again - in a coalition with the far-right

Slovak National Party headed by the controversial

Ján Slota, and the radical-left

Združenie robotníkov Slovenska headed by the colourful

Ján Ľupták, a mason.

During the following period, he was constantly criticized by his opponents and Western countries for an autocratic style of administration, lack of respect for democracy, misuse of state media for propaganda, corruption (which is still prevalent today) and the shady privatisation of national companies that occurred during his rule. Privatisation during the 1990s in both Slovakia and the Czech Republic was harmed by widespread unlawful asset stripping (also described by the journalistic term of tunnelling).

The U.S. State Department in 2010 reported:

"

The government generally respected the human rights of its citizens; however, there were problems in some areas. Notable human rights problems included some continuing reports of police mistreatment of Romani suspects and lengthy pretrial detention; restrictions on freedom of religion; concerns about the integrity of the judiciary, corruption in national government, local government, and government health services; violence against women and children; trafficking in women and children; and societal discrimination and violence against Roma and other minorities."

The Roma form a sizeable minority in Slovakia, although officially counting only 90.000 in reality the number is approximately half million. Of this, 330.000 live in "unfavourable social conditions",[4] a euphemism for being beyond the line of poverty, many of them living in Roma settlements (Slovak: Rómske osady). In the year 2000 there were 620 such settlements in Slovakia, by 2009 their number increased to 691. Here, people live in self-made houses constructed on land they do not own, settlements are often without electricity, waste disposal or sanitary water.

The situation of Roma in Slovakia is an issue where both local and foreign observers consistently agree on the magnitude of the problem as well as its urgency and importance. The key issues being stressed on both sides of the debate seem to differ quite radically, however, an example being various Slovak governmental proposal of taking the Roma children from their homes into boarding schools, which is considered to be one of the best solutions to the education of the local Roma people in Slovakia, an idea that has been severely criticized from abroad.

Issues concerning the Roma minority:

- Segregation of the Roma minority

- Forced evictions

- Discrimination during hiring

- High percentage of Roma children ending up in special schools for the mentally handicapped

- High recreational drug use consisting primarily of tobacco, alcohol and toluene

Other known issuesIssues concerning Law enforcement- Misuse of power in the Slovak police

- Physical abuse of both accused and witnesses

- Casual abuse of selected groups by the police, particularly Roma, prostitutes and recreational drug users

Other cases- Forcing the

Hungarian minority to speak

Slovak through language legislature

- Poor LGBT rights implementation (as an illustration, the first Bratislava Rainbow Pride on May 22, 2010 ended with several attendees beat up)

- Drug possession criminalisation (in most cases punishable by a stricter sentence than rape or assault)

- Immigration issues (for example the expulsion of Mustapha Labsi in violation with international law)

- Various loopholes in legislature make Slovakia a target for international arms dealers (making shipments for example from Slovakia to Liberia in 2001, in violation of a U.N. embargo)

- Political surveillance use

- Corruption in the judiciary, lengthy pretrial detention, lengthy trials

- Domestic violence against women and children[/size]