|

|

Post by pjotr on May 19, 2017 0:25:49 GMT 1

Dear Jeanne, Bonobo, Tomek, Tufta and Mike, Poznań has a special charm with Polish and German-Prussian elements. I remember the city as a child and teenager (14 and 17 years old, I visited the city in 1984 and 1987), and have very good, sentimental, romantic and thus sweet memories about the city, my Polish grandparents there, my Polish uncles and aunts there and my two Polish cousins. The Communist Peoples Republic of Poland Zloty was cheap and our Dutch Guilders were a tough currency, so going to the cinema as a child, going for lunch or dinner in a Bar Mlechny or a Polish restaurant in the Old town or in one of the Orbis state hotels was cheap for us. The same counted fro the little charming Zoo in Poznan, we visit a lot as children, my sister and I. I just loved walking along my grandparents Mickiewicza street and go to the state supermarket, Sam, on the Dąbrowskiego boulevard, and than to the city center over the bridge that went over the rialwaytracks along Teatr Wielki im. Stanisława Moniuszki (Great Theatre or Opera), and then towards the old city center passing some new era late 20th century Peoples Republic buildings, old churches and large buildings probably from the Prussian era. I loved the old Gothic, Baroc & Rocco churches, the museums, the parks and simply the atmosphere of Poznań. What my mother disliked about Poznań is what I loved about Poznań, it's layerd history, and the mix of Polish and Prussian (German( influences. I like Old German cities and towns and therefor also the Posen element of Poznań. My mother has a favor for Warsaw and Kraków, because the atmosphere there is more Polish. My mother considered the atmosphere in Poznań to be German, she disliked the Posen element of Poznań, being a 100% Western slavic Polish woman with no German roots. My Polish mother also dislikes Germany and Germans. She doesn't hates Germans or Germany, but simply dislikes the German atmosphere, the German language and German people in general. (That is a typical trait of the older Dutch and Polish generations.) The German element is the heavy tall buildings like the Imperial Castle in Poznań, popularly called Zamek (Polish: Zamek Cesarski w Poznaniu, German: Königliches Residenzschloss Posen), the classist and Jugendstil buildings (also the appartment building Mickiewicza 24 where my babcia and dziadek lived from 1945 until my babcia's death in 1987. -My dziadek died in 1977-).  The Prussian Imperial Castle in Poznań The Prussian Imperial Castle in PoznańAs a child and teenager I loved the vibrant day and night life of this city with 551,627 citizens. I remembered in the evenings and nights hearing the trams driving over the tram tracks, busses, cars, nightcabs and truckdrivers with their trucks (It was a transport, commercial, trade and production Urban Agglomeration back then and today), and probably the trains that passed nearby. Ofcourse I had the luxery of visiting and staying in my grandparents apartment and visiting several aunts and uncles of my mothers family and probably some friends and acqaintances of them, which made these visits different than someone who was a tourist. What does remains are memories about people, pedestrians, architecture, infrastructure, atmosphere, the fact that the city had some Polishness despite the heavy German influence. The Polishness was in the people, in their humanity, in the spirituality of the Roman-Catholic churches and in the faith of the people themselves in their homes, in the streets where they walked, in their cars, in their gardens, in their parks and in the bars, restaurants and bar mlechny they visited. Like Bonobo described old Krakow or Poland during communism it is a fact that a lot of the buildings were old and grey and brown due to the pollution of coal and Lignite (brown coal), and the fact that a lot of old communist cars produced some air pollution too. The Old Warszawa's and FSO Syrena's that drove around next to the two-stroke straight-twin engines of the Polski Fiat 126p, and other East block cars. Nex to that you had the coal driven communist steam trains, and communist era trucks, vans (FSC Żuk and ZSD Nysa 522) and old busses. Maybe a lot of people also used wood next to coals to get some heating? But next tot the greyness there was a lot of city green in the forms of old city trees and the trees and plants in the city parks. I remember that due to the Western location of Poznań, the Polish family (of whom most originally came from Southern Poland - somewhere inbetween Krakow and Katowice -the Austrian occupied territories- ) weren't particulary fond of Germans despite of the half German heritage of one of the uncles. There was not so much personal hatred against people, but distrust about future intentions of Germans. In the case of Eastern-Germany that wasn't that strange at all, because these Prussian strict East-German communists with their Prussian militarist tradition in their East-German NVA (Nationale Volksarmee, National Peoples Army) army were not to be trusted. Twice large East-German military concentrations were near Poland. In 1968 when the East-Germans considered attacking Czechoslovakia to support the Sovjets and in 1981 when the East-Germans considered entering Poland. So, Poznań was great in the seventies, eighties and probably in the nineties and 21th century too. Poznan today will be cleaner and more modern. When I look at Mickiewicza 24 with Google maps I see that the building has changed completely and the street too. www.google.nl/search?q=poznan&oq=poznan+&aqs=chrome..69i57j0l5.2686j0j7&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8#q=mickiewicza+24+pozna%C5%84+PolskaIf you look at this Google map link you see the building with Kobiet and materiały biurowe, the window in the corner where the lady is standing on the street under the Kobiet sign and the two windows under the materiały biurowe sign was the large one room apartment where my grandparents lived in Poznan. They shared the hall, the kitchen, the bathroom, the attic, and a cool room (they didn't had a refrigerator) with neighbours. As child you remember your grandparents, that my dziadek was a kind, humble and rather old fashionate man with a hat, suit, small moustache and his typical old generation Polish gentleman behavior and gentle sense of humor. They were rooted in prewar Poland, my dziadek was born in the late 19th century and my babcia in the early 20th century. They had to leave Warsaw in 1944/45 and start a new life in Poznań, the city of my babcia's familymembers. In the twenties my dziadek met my babcia in Poznań where they lived for a short time before leaving for Warsaw, where they lived during the twenties, thirties and early fourties. Due to the Uncle with German roots and connections they found out that the apartment in Mickiewicza 24 was vacant in late 1944 and early 1945, because the Volksdeutsche Nazi (Polish German) which had lived in that apartment was gone (fled or murdered, I don't know). They had some possessions of the Volksdeutscher, which he had left. Some furniture, some paintings, and some Tableware. My grandparents could take few possesions from Warsaw and a lot of their posessions were looted at the end of the war in the chaos of the war ending. My granmother had spend months in Austria in Mauthausen where she did slave work for Austrian farmers and my dziadek was wondering around in Poland after he had escaped from execution in Warsaw by the German/Austrian Waffen-SS. He switched sides from a group of young Warsaw Polish men to a group of Old Polish men. The young men were shot shortly afterwards. By miracle my grandmother escaped from Austria and my grandfather managed to come to Poznań (without means of transportation, income, or places to stay), and my mother and her sister (their daughters) traveled from town to town, being helped by connections, relatives, acqaintances and people who felt empathy for the small (little) girls. It is a miracle that both the Warsaw and the Poznań family survived the war, because the Nazi occupation was anti-Polish, and saw Poles as Slavic subhumans. My Dutch family on my fathers side had hard times in Rotterdam (the bombed Dutch city which was destroyed by bombing on 14 May 1940) too, but you can't compare the Polish suffering with the Dutch suffering. The Germans were irritated with the reluctance of the Dutch to join the Great Germanic Empire of the Nazi Third Reich and became disillusioned with the stubborn Dutch. You had Dutch Nazi's and collaboration with the Germans ( a whole lot more than in Poland, because many Dutch felt themselves to be fellow Germanic people), but not enough in the mindset of the German/Austrian Nazi authorities. To much Dutch people simpy refused to becoma hard line Nazi's. The Germans had hopped the Netherlands to be the same as Austria, but the majrotiy of the Dutch people was less enthousiast then the Austrians who cheerfully welcomed the German Wehrmacht and Waffen-SS forces. Adolf Hitler didn't came to the Netherlands for a victory parade or a speech for large crowds of Dutch people. The Reichskommissar for the Occupied Dutch Territories Arthur Seyss-Inquart was a notorious Austrian Nazi.  Hans Frank and Arthur Seyss-Inquart at a parade in Kraków, 1941 Hans Frank and Arthur Seyss-Inquart at a parade in Kraków, 1941During World War II, he served the Third Reich in the General Government of Poland and as Reichskommissar in the Netherlands. He fully supported the heavy-handed policies put into effect by Hans Frank , including persecution of Jews. Following the invasion of Poland, Seyss-Inquart became administrative chief for Southern Poland, but did not take up that post before the General Government was created, in which he became a deputy to the Governor General Hans Frank. He was also aware of the Abwehr's murder of dozens of Polish intellectuals. I say that the persecuation of Roman-Catholic Poles and jews in the beginning was worse in Poland then in the Netherlands. The Germans didn't hunt down and murdered Dutch teachers, professors, journalists, scientists and other intellectuals. The persecution of Duch jews started later in the Netherlands, because first the Nazi authorities wanted to show a friendly, fellow Germanic face to the West-Germanic Duch, their so called Brudervolk and Bruderstaat. The Duch didn't felt that way and so soon the things would change to the worse, but they would never become as bad as in Poland. The persecuation of the Polish jews started right away in 1939 with the mass murder of Polish jews by the Einsatzgruppen der Sicherheitspolizei und des SD. The main culprits were members of the Sicherheitspolizei ( Sipo) – consisting of Geheimer Staats- (Gestapo) and Kriminalpolizei (Kripo) –, of the Sicherheitsdienstes ( SD), the Ordnungspolizei ( Orpo) and the Waffen-SS. But also units of the German Wehrmacht intelligence agency Abwehr and Wehrmacht army units took part. Bad elements of the German minirotity in Poland of Volksdeutsche took part in the Intelligenzaktion ( Intelligentsia action) which was a secret genocide conducted by Nazi Germany against the Polish élites ( the Polish intelligentsia, teachers, priests, physicians, et al.) early in the Second World War ( 1939– 45). The genocide operations were conducted to realise the Germanization of the western regions of occupied Poland, before territorial annexation to the German Reich. The executioners of the Einsatzgruppen death squads and the local Volksdeutscher Selbstschutz, the German-minority militia, pretended that their police-work was meant to eliminate politically dangerous people from Polish society.  Members of the Volksdeutscher Selbstschutz in police uniforms Members of the Volksdeutscher Selbstschutz in police uniformsThe Intelligenzaktion was a major step to implementing Sonderaktion Tannenberg ( Operation Tannenberg), the installation of Nazi policemen and functionaries — from the SiPo (composed of the Kripo and Gestapo), and the SD ( Sicherheitsdienst) — to manage the occupation and facilitate the realisation of Generalplan Ost, the German colonization of Poland. Among the 100,000 people killed in the Intelligenzaktion operations, approximately 61,000 were of the Polish intelligentsia, whom the Nazis identified as political targets in the Special Prosecution Book-Poland, compiled before the war began in September 1939. The Intelligenzaktion occurred soon after the German invasion of Poland (1 September 1939), and lasted from the autumn of 1939 until the spring of 1940; the Nazi genocide of the Polish nation continued with the operations of German AB-Aktion operation in Poland. People in Poznań suffered terribly from the Germanisation policies of the Nazi's and the Intelligenzaktion too. In Poland in general you feel the heritage of the war more than in the Netherlands, because more people were massacred, tortured, murdered and hurt there than in the Netherlands. During the German occupation of 1939–1945, Poznań was incorporated into the Third Reich as the capital of Reichsgau Wartheland. Many Polish inhabitants were executed, arrested, expelled to the General Government (the territory of Warsaw, Radom, Kraków and Lublin) in which or used as forced labour; at the same time many Germans and Volksdeutsche ( Polish Germans) were settled in the city. The German population increased from around 5,000 in 1939 (some 2% of the inhabitants) to around 95,000 in 1944. One of these Volksdeutsche, was the Nazi who lived in my grandparents apartment in Mickiewicza 24. The man could have been a Volksdeutscher Selbstschutz member, or part of the administration of Reichsgau Wartheland, the Nazi German administration of Posen (the German name of Poznań). For some reason my Polish family from my babcia's side managed to survive (maybe due to the German family connections and German family of my Polish uncle with German family roots. He was not a collaborator nor a nazi, but used his connections pragmatically to help his Polish family and wife). Again it was a miracle that my Polish dziadek, Babcia, mother and aunt survived the war in Warsaw, Mauthausen and other places. It was a fifty fifty case, several times they could have died, but God had mercy on them and spared them and granted them a life in Post-War Poznań. I remember that we found Nazi lecture of that Volksdeutsche, my grandparents had put away on top of a shelf in the dark hall in the dark in brown paper that was covered by decades of dust. We found Jahrbücher des Dritten Reichs from 1933 until 1938, Nazi Art magazines with Adolf Hitler on the first page, and awful mean nazi stories inbetween the rather nice art images, beautiful drawn social realistic Waffen-SS books about heroic fighting handsome, tall, blond, blue German soldiers, who were ofcourse victorious towards the enemy. And books of the various army sections; Wehrmacht, Kriegsmarine (Navy) and Luftwaffe. My father didn't want to take it with us to the Netherlands, being afraid that the East-German border guards or Vopo's (East-German police) would catch us with nazi lecture. That would have been embarrassing, awkward, and not so wise. We already smuggled that old Polish and German paintings, table ware and other antiques outside of Poland. So I have lot's of memories about Poznań. For a long time I also remembered the atmosphere, smell and sounds, but now I have grown older these memories sadly faded away. I only have memories about the images, people and experiences today.  Polish Germans of the Volksdeutscher Selbstschutz Nazi militia in Western Poland during the Second World War Polish Germans of the Volksdeutscher Selbstschutz Nazi militia in Western Poland during the Second World WarCheers, Pieter P.S.- I have to say that there were also Volksdeutscher who were anti-Nazi. Some of the German Poles also were active in the Polish resistance. Władysław Anders, Emil August Fieldorf, Adam Fastnacht, Wilhelm Orlik-Rückemann, Maximilian Kolbe (Kolbe had a German father), Józef Haller had German roots. |

|

|

|

Post by pjotr on May 22, 2017 16:33:47 GMT 1

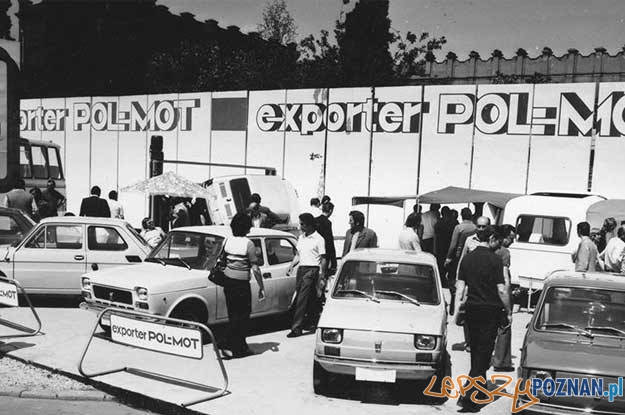

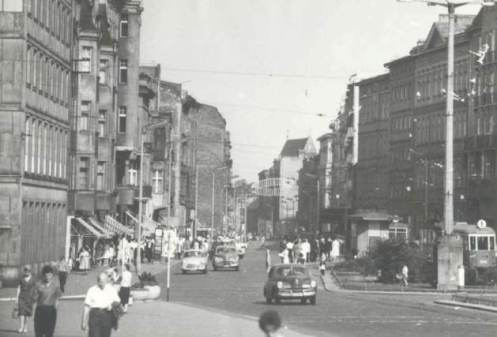

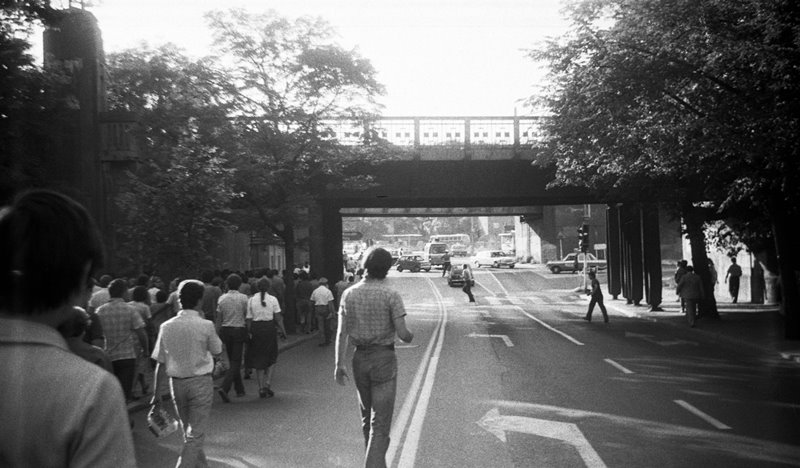

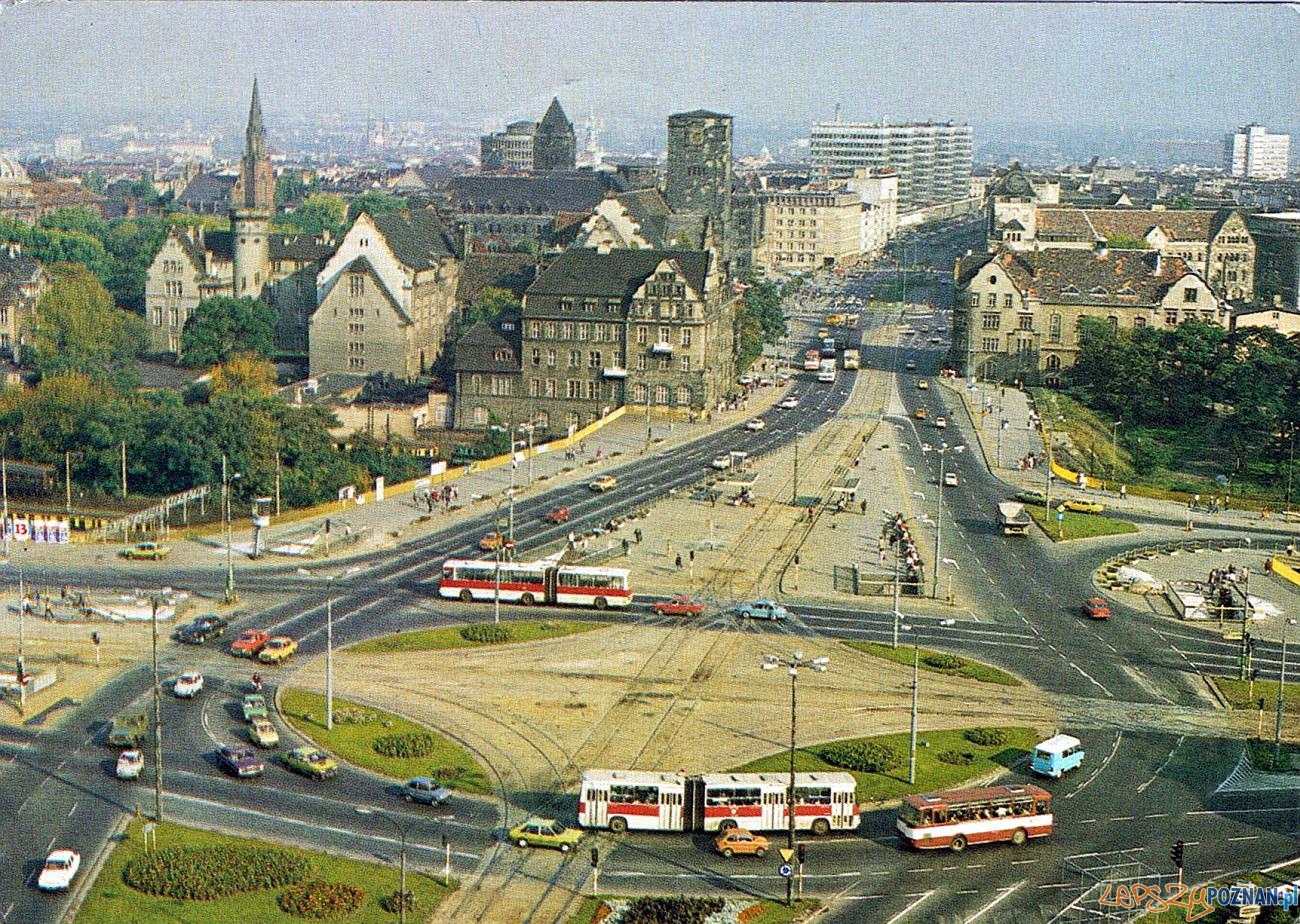

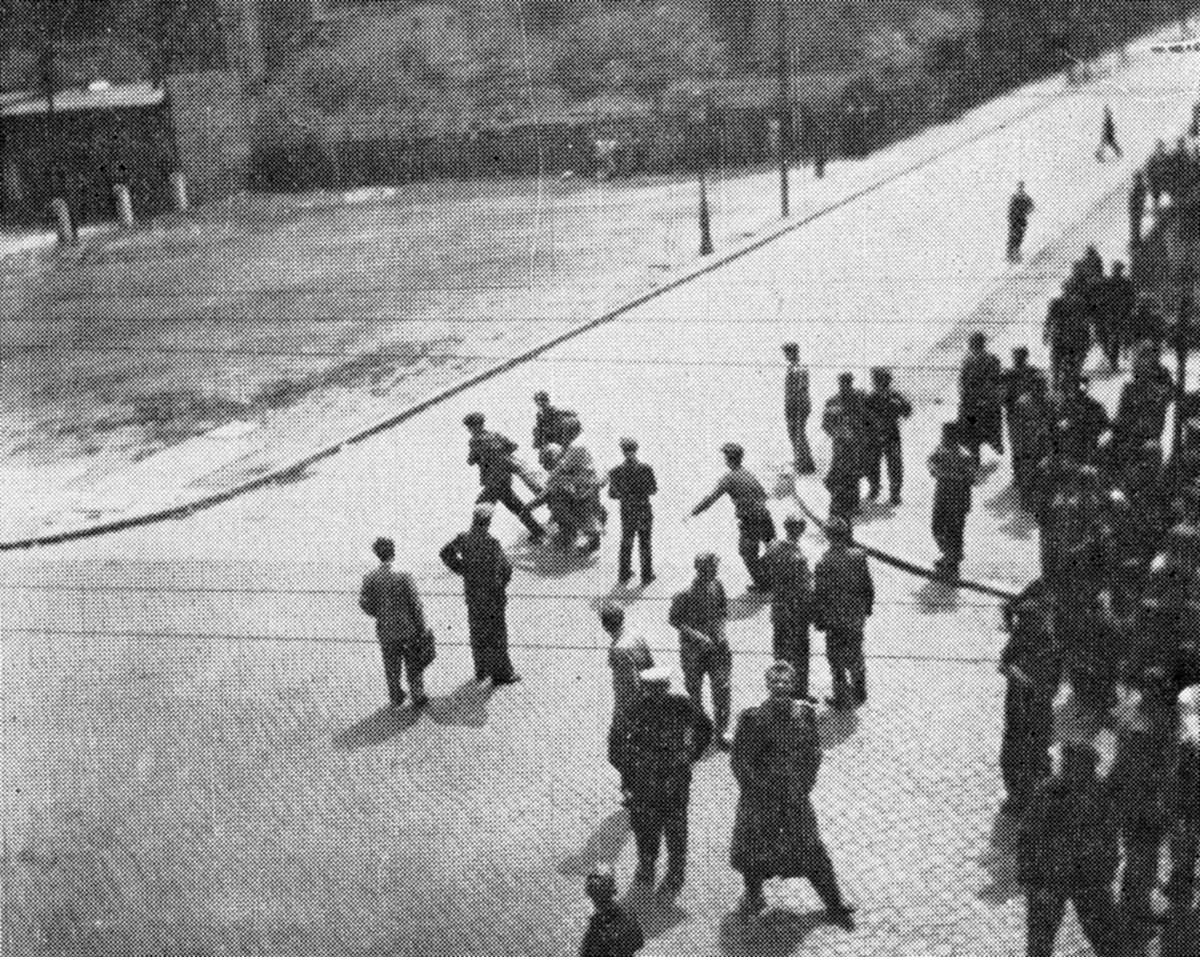

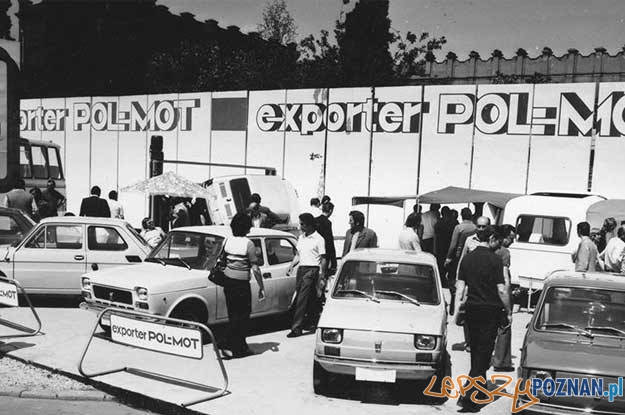

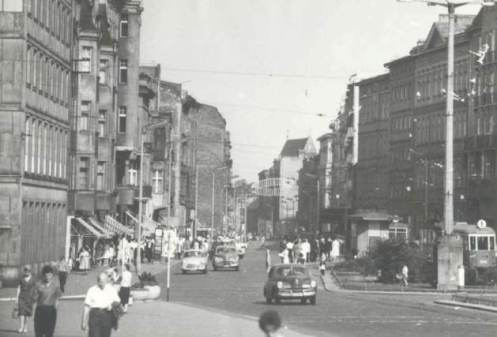

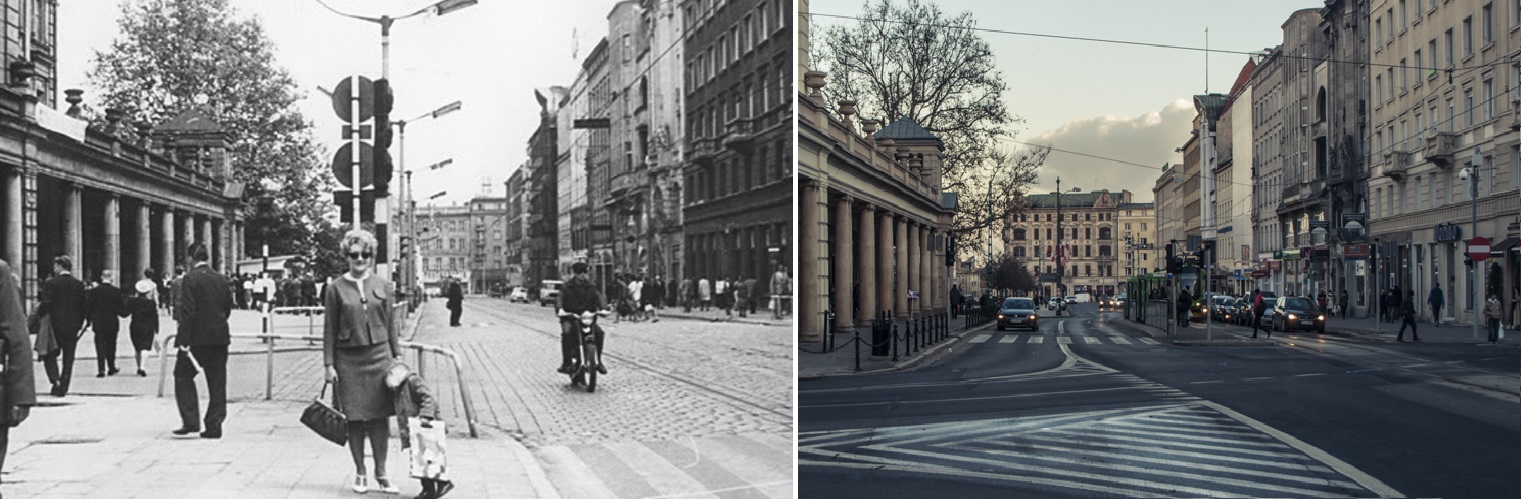

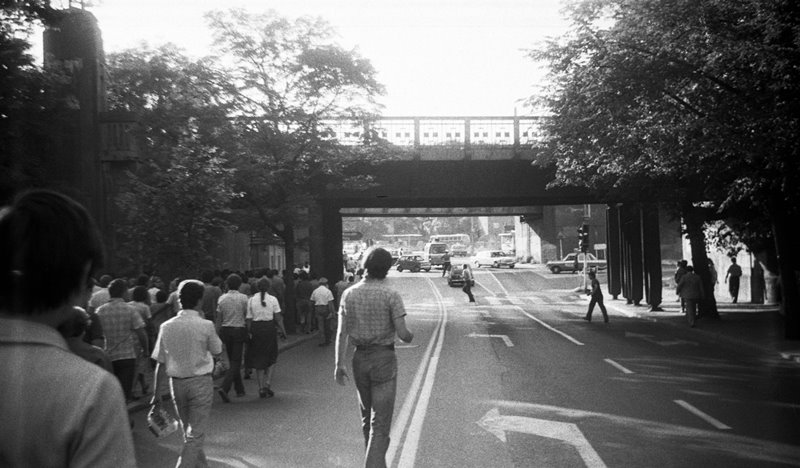

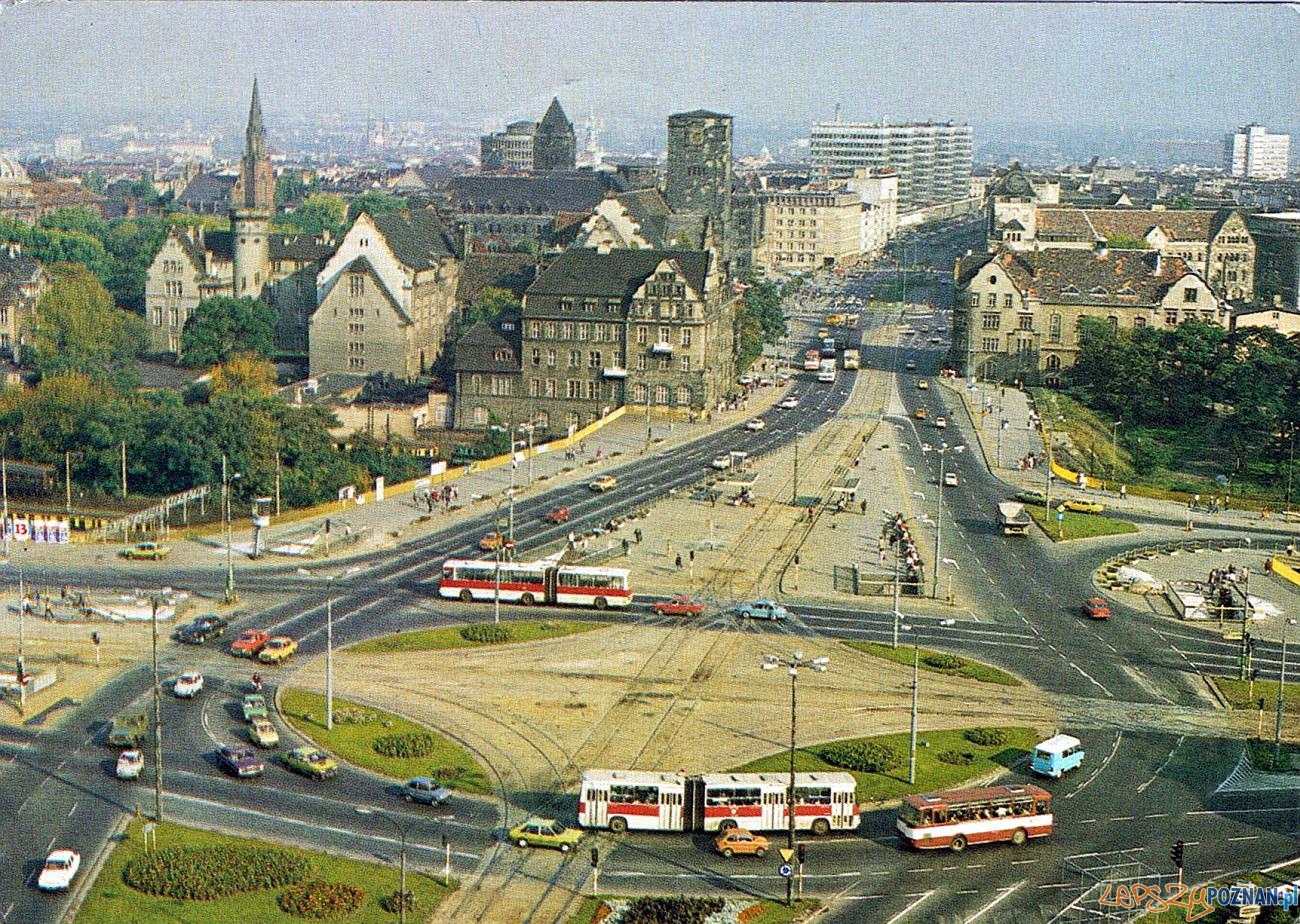

Dear Jeanne, Bonobo, Tomek, Tufta and Mike and others, There are strange things one can remember from childhood and teenage years. One can remember a place, an era, a decade, a year, a month, a week, a day, a particular moment in that day early morning, halfway the morning, late in the morning, the afternoon, late afternoon, beginning of the evening, half way the evening, late in the evening or at night. A certain hour, quarter of an hour or even a minute. One can have memories that read like a moment in a novel, a prozaic poem or a scene in a romantic high quality art house movie or documentary. Quintessence, quality of life and these essential moments when time seems to halt for a moment. I have these scenes which will stay forever with me from Poznań. 1975, 1976, 1977 (I don't remeber what years excactly, excuse me I was 5, 6 and 7 years old). There were no cell phones, no digital camera's, no internet, no e-mail, no Facebook, no Polish Culture Forums, no youtube chanals, no audio cd players and no DVD's back then. Few people had videorecorders and there were no Windows or Apple PC's, I-pads/talblets or drones who filmed everything. People still read paper books, still wrote letters and postcards on paper and postcards, and they still used the old fashionate wired telephone. Color tv started getting popular and replaced the black and white tv. The Berlin wall, the Iron curtain, the Comecon, Warsaw Pact still existed and the Polish United Workers' Party (PUWP; Polish: Polska Zjednoczona Partia Robotnicza, PZPR) still governed the Polish People's Republic and the Służba Bezpieczeństwa Ministerstwa Spraw Wewnętrznych (Security Service of the Ministry of Internal Affairs) was present in the society. Probably not visibly but they were present, also in Poznań. No doubt they would have been interested in that alien family from the Netherlands who came in that beige silver Ford Traunus Bravo with Dutch number plate, a quite unusual sight in Poland. I knew that the SB listened to my mothers and babcia's (grandmothers) phone conversations between Poznań and Vlissingen (in the Netherlands). We knew that they checked letters, postcards and packages with food or maybe medicines that came from the Netherlands. I remember in the late seventies and especially in 1984 that also in Poland (not only in the DDR, Czechoslovak- and Hungarian peoples republic) I saw uniforms everywhere in Poznań. Communism for us had a militarist element. We saw the blue grey uniforms of the Milicja Obywatelska with their blue grey peaked caps, and the equal shaped grey green uniforms of the soldiers and officers of the Polish Peoples army ( Siły Zbrojne Polskiej Rzeczypospolitej Ludowej ). The visibility of these uniforms on the streets of Poznań made it clear that it was not a normal Western democracy but a dictatorship in which the Milicja Obywatelska was present everywhere. I remember also vehicles, vans (FSC Żuk or ZSD Nysa 522), trucks and cars of the paramilitary-police formation ZOMO (Zmotoryzowane Odwody Milicji Obywatelskiej; Motorized Reserves of the Citizens' Militia in English) when there were tensions in the city.  1956 protests in Poznań, Polish People's Republic 1956 protests in Poznań, Polish People's Republic  I remember this impressive statue in Poznań to commemorate the events that took place in Poznań in 1956, but also the workers strikes and rebellions which were bloodly repressed by the communist regime in 1968, 1970, 1976, 1980 and 1981 (Marial Law). We took images there and laid some flowers there. I remember this impressive statue in Poznań to commemorate the events that took place in Poznań in 1956, but also the workers strikes and rebellions which were bloodly repressed by the communist regime in 1968, 1970, 1976, 1980 and 1981 (Marial Law). We took images there and laid some flowers there.The large ZOMO column of trucks, vans and cars must have been in 1984. I saw a large formation driving from Dąbrowskiego in the direction of the Adam Mickiewicz University, the Great Theatre and the Old townsquare (Stary Rynek) in Poznań. I didn't knew what was going on and there was no internet, blogs, news sites to get informed what was going on? Hooliganism didn't arrived in Poland yet. You had Solidarność ( NSZZ „S”), but it was after the Martial law of 1981. Poznań had the name of a rebellious city due to the rebellion of June 1956. I remember that there was some economical depression, some problems with alcoholism and I saw some disturbances due to that alcoholism during the day and evening. But to be honest that wasn't much different than in the Netherlands or any other European country with an alcohol (beer, vodka, genever, whiskey, wine, bacardi.screwdriver [=Vodka+jus de organge mix] culture.). This ZOMO force didn't felt good. They were scary, with to many, and somehow later I must have figured out that these must have been political hardliners (A police force of loyal communist party members, because they had to break dissident forces, anti-communist workers revolts, counter revolutionary activities, rebellion and etc.). I was young when I looked at them back in 1984 (the large column of ZOMO trucks, vans and cars, blue grey like the normal Milicja Obywatelska, but different in uniforms and seize). I was 14 years old and somewhat a late blossomer, not quite my age. A dreamer, a little bit childish for a 14 year old, but already very interested in history and culture. But I certainly didn't know exactly what communism (Marxism-Leninism), socialism and democracy ment. I knew the differences between East and West and that my grandparents, uncles and aunts and cousins in Poznań weren't free. We were there and it was a holiday for me, and so it was relaxed, cosy and thus pleasent. I never felt threatened by Milicja Obywatelska officers, even when they stopped my father once when he drove to fast over a wooden bridge with his Ford Taunus. But the police officer was friendly, nice and forgiving. I will never know where this ZOMO force was heading for? A riot, disturbances of drunken people going out or a large scale exercise? I felt a little bit what a communist dictatorship was at that moment, that was such kind of moment. Another moment was when we in the Netherlands had to go to the Communist Polish embassy in The Hague, where very unpleasent Polish Apparatchiks worked, blunt, rude, square faced, annoying, communist civil servants. It was a lot of stress for my mother to arrange our visa's due to the slow, bureaucratic and deliberate rude communication of this Polish embassy personel. Her Polish passport was taken away from her because she married my father in 1967 and left the great and socialist Poland to go to that Petit Bourgeois, Kulak, Fascist, Imperialist, Neo-colonialist, revisionist, Zionist, evil tiny Western country in Western-Europe, the Netherlands. That evil ally of America and the fascist, reactionairy, chauvinistic West-Germany. This fact was very humiliating for my mother who ofcouse was connected to her Polish roots. Her first 33 years she had lived, studied and worked in Poland. Her first 9 years in Warsaw, and after that probably 10 years in Poznań (pirmary school, highschool and some Polytechnic school) and after that back to Warsaw to work and live where her older sister and other familymembers were too. I told you before that I liked and like Poznań very much with it's layers of old Polish history, Prussian heritage and new Polish history. For me as a child and teenager ofcourse it was a very Polish city. For my mother, who is 100% Polish, rooted in Polish culture, language, traditions, customs, Polish Roman-Catholicism and her very Western Slavic Polish heritage, Poznań was too German in it's atmosphere and even people. The Poznanski dialect, spoken in Poznań and to some extent in the whole region of the former Prussian annexation (excluding upper Silesia), with characteristic high tone melody and notable influence of the German language was not my mothers Polish. I don't know if my mother spoke Standard Polish, the Warsaw dialect or the Masovian dialect of her fathers Eastern-Polish and Warsaw family members. I also don't know if the Poznań family branche of my grandmothers side of the family spoke the Poznanski dialect? Probably not, because most of them originally came from Southern Poland.   Ulica Mickiewicza (street) in Poznań Ulica Mickiewicza (street) in Poznań Dąbrowskiego boulevard in Poznań Dąbrowskiego boulevard in PoznańSo while I understand my mothers favor for Warsaw, fondness of Kraków (the spiritual, original capital of Poland in her eyes, and the city of the Polish intelligentsia of artists, university professors, university students, theatrical playwrights, musicians, poets, writers, philosophers, intellectuals, journalists of quality newspapers and magazines and etc.) and apreciation of Poznań as the city where her parents, aunts, uncles, cousins, nephews and nieces lived and some old friends of her primary and highschool years. But I can't say she was fond of Poznań. I remember how enlightened my mother was when we travelled by train from Poznań to Warsaw in 1984. She saw old friends and colleages back there. She saw her old apartment back, she had to leave behind in 1967, right next to the Palace of Culture in the heart of Warsaw in a modern apartment building (we stayed there for a few days). And how happy she was when she met old Varsovian familymembers in Warsaw again. To be frank, for me Warsaw wasn't beautiful back then in 1984, it was grey, large and not full of life like today. I longed back for Poznań, my babcia, my cousin to play with, the zoo, the cinema, the Poznan streets and boulevards, the Poznań atmosphere. Also the melancholic, romantic, multi-layered aspect of Poznań. If you are a sensitive, poetic, creative soul, Poznań will touch your heart, because that city has something. Maybe it is that mix of Old Polishness, Prussian Germanism and New Polishness (the polonization of Poznań after the expulsion and flight of German population in Post-war Poznań. Poznań was free of Germans, accept my Polish uncle with German roots) that appealed to me. Still for my mother Poznań was too German, due to the German influence on the original Polish population of Poznań. It is a proof that you can try to purify a city, to ethnically cleans a city of foreign influence, but that you can't get history, cultural and linguistic influences out of people. Poznań was to much Posen (the German name for Poznań) for my mother. For a long time dear Bonobo, Jeanne and other Forum members Poznań was in my mind and memory as a novel on your bookshelf (as Nikolai Gogol Saint Petersburg tails about the Nevski Prospect or Fyodor Dostoyevsky's haunting atmoshere in Crime and Punishment -ofcourse my Poznań experience being the positive of the Crime and Punishment negative-), because it was a place with a special atmosphere, special people, special light, special, streets, boulevards, alley's, pathways, courtyards, by-roads (short cuts), pavements (sidewalks), entries (hallways), lobbies, stairs, balconies, roofs, chimney-shafts, old walls drawn by time, natural city scape relief, empty spaces and crowded spaces, tramrails, the traces of trucks, buses and cars on roads, the tall, large, medium-sized and small city trees, plants and flowers. And without having a camera I loved to watch and observe pedestrians, the strangers, Poznań people on the streets, boulevards and squares. The diversity of people despite the limited choice in clothes in the peoples republic (probably many people made their own clothes or there must have been clothes makers). Men, women and children, teenagers, youngster, young adults, babies with their mothers. Standing still and talking with each other. A conversation on the street. People sitting on street benches or in the park. People walking very fast like in every large city, going to their job, to an appointment (meeting), shopping or meeting a loved one or relative. I loved to watch the street Mickiewicza from my grandparents apartment in Mickiewicza 24. And I loved to go outside and walk outside, not understanding what poeple were talking about or what words on signs, billboards or advertisements said. It fed my imagination. Seeing, hearing, smelling, tasting, experiencing things. I experienced Poland, the Peoples Republic Poland as a child and teenager. I experienced Poznań, and I liked the city, the people, the museums, the cinema, the zoo, the homes of my grandparents, uncles and aunts and friends of my mom. I liked Stary Rynek, the Opera House, the churches, Park Cytadela and the Wielkopolskie Muzeum Niepodległości and the Muzeum Armii Poznań, the Modern buildings next to the old ones, even if they were ugly Communist time grey, concrete buildings with some steal and glass. I remember that one of the large boulevards in the city near the Imperial Castle was called ulica Armii Czerwonej (the Red army street). Another street or boulevard was called after Stalin. The Stalin allee or boulevard or something. Maybe some old Poznań residents will remember that. Today the Royal Castle in Poznań (Polish: Zamek Królewski w Poznaniu) is an impressive sight very near to the Old Town.   I haven't been in Poznań since 1987 so, there will probably be a lot of modern buildings built in the late eighties, nineties, the first 10 years of the 21th century and the last seven years. Bonobo posted a lot of images of the new buildings in a thread in this section. I loved watching them. There will be probably new sections of Poznań which are brand new, and next to that I hope that there are completely new sections of old streets, boulevards and squares due to new buildings, between, in, over and next to old buildings. The exiting thing about cities is that they change and that the charm of a city is the layer of building styles, historical architectures styles, combinations from old newer and Ultra-Modern buildings. That's what I like about Berlin, Warsaw, Rotterdam, London, and probably also Poznań.   I remember this Modern building in the city center of Poznań from the eighties I remember this Modern building in the city center of Poznań from the eighties Modern hotel in Poznań  Poznań was rebuilt after World War II and had become the administrative, industrial, and cultural centre of western Poland. As one of Poland’s largest industrial centres, Poznań had and has varied industry that includes metallurgical works; textile mills; clothing and food-, metal-, and rubber-processing plants; chemical facilities; and an automobile factory. Since 1921 it has been the site of a major international trade fair. Due to the expulsion and flight of German population Poznań's post-war population was almost uniformly Polish. The city again became a voivodeship capital; in 1950 the size of Poznań Voivodeship was reduced, and the city itself was given separate voivodeship status. This status was lost in the 1975 reforms, which also significantly reduced the size of Poznań Voivodeship.  Wielkopolskie fotopolska Wielkopolskie fotopolskaThe Poznań 1956 protests are seen as an early expression of resistance to communist rule. In June 1956, a protest by workers at the city's Cegielski locomotive factory developed into a series of strikes and popular protests against the policies of the government. After a protest march on 28 June was fired on, crowds attacked the communist party and secret police headquarters, where they were repulsed by gunfire. Riots continued for two days until being quelled by the army; 67 people were killed according to official figures. A monument to the victims was erected in 1981 at Plac Mickiewicza.  Poznań's Cegielski locomotive factory Poznań's Cegielski locomotive factoryThe post-war years had seen much reconstruction work on buildings damaged in the fighting. From the 1960s onwards intensive housing development took place, consisting mainly of pre-fabricated concrete blocks of flats, especially in Rataje and Winogrady, and later (following its incorporation into the city in 1974) Piątkowo. Another infrastructural change (completed in 1968) was the rerouting of the river Warta to follow two straight branches either side of Ostrów Tumski.  Communist style pre-fabricated concrete blocks of flats in in Rataje, Poznań. (P.S.- Ofcourse you had the same sort of constructions in Western-Europe. Today problematic neighbourhoods in the Netherlands, France (the balieu's), Germany and Belgium) Communist style pre-fabricated concrete blocks of flats in in Rataje, Poznań. (P.S.- Ofcourse you had the same sort of constructions in Western-Europe. Today problematic neighbourhoods in the Netherlands, France (the balieu's), Germany and Belgium)  Communist style pre-fabricated concrete blocks of flats in in Winogrady, Poznań. Communist style pre-fabricated concrete blocks of flats in in Winogrady, Poznań.Poznań is home to several institutions of higher education, including Adam Mickiewicz University (University of Poznań), founded in 1919, and Poznań Technical University, founded in 1921; numerous scientific institutes sponsored by the Polish Academy of Sciences; operatic, orchestral, and dance centres; Poland’s oldest zoological garden; and a number of theatres. The cathedral (erected 968) was completely rebuilt in the Romanesque style following upheavals in the 11th century, though later additions gave it a predominantly Gothic appearance. The cathedral’s gilt-domed Golden Chapel is the tomb of Poland’s early rulers. Also of note is Poznań’s 16th-century town hall, featuring a clock tower from which two mechanical goats appear at noon to lock horns. In addition to the National Museum there are notable museums of archaeology and of musical instruments. Poznań has an international airport and excellent transportation connections to major cities in Poland and the remainder of Europe.  Adam Mickiewicz University (University of Poznań) Adam Mickiewicz University (University of Poznań) Students of the Adam Mickiewicz University (University of Poznań) Students of the Adam Mickiewicz University (University of Poznań)Cheers, Pieter Sources: Pierter's memory, wikipedia and Britannica |

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on May 22, 2017 22:07:03 GMT 1

Oh la la, I will try to gradually refer to parts of your great post. The Communist Peoples Republic of Poland Zloty was cheap and our Dutch Guilders were a tough currency, so going to the cinema as a child, going for lunch or dinner in a Bar Mlechny or a Polish restaurant in the Old town or in one of the Orbis state hotels was cheap for us. Yes, communist currency was extremely low in value, it was enough to sell 500$ in the black market to live a decent life for a full year in 1980s. It substantially changed after the Polish access to the Union. |

|

|

|

Post by pjotr on May 25, 2017 2:35:14 GMT 1

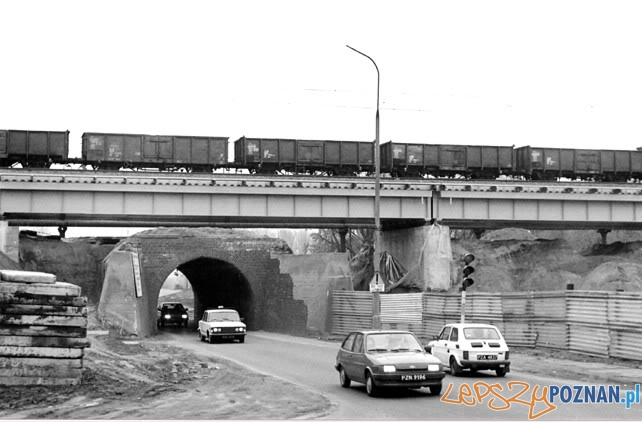

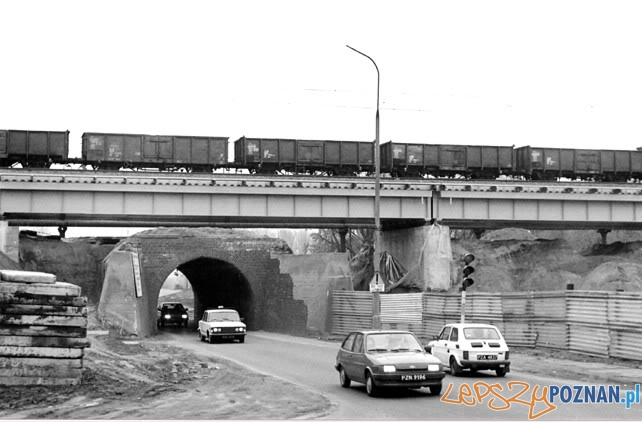

Images of Poznań I could find on the Internet which remind me of my childhood and teenage memories as a 5/6/7 and 14 and 17 year old.  The small Stare Zoo in Poznań The small Stare Zoo in Poznań  I remember this small Indian elephant from the Stare Zoo in Poznań I remember this small Indian elephant from the Stare Zoo in Poznań Small Indian elephant in the Stare Zoo in Poznań Small Indian elephant in the Stare Zoo in Poznań Zwierzyniecka, Poznań - 1969 Zwierzyniecka, Poznań - 1969  Ulica Słowackiego w Poznaniu Ulica Słowackiego w Poznaniu   Most teatralny w Poznaniu Most teatralny w Poznaniu        All these images I searched for and found are near Mickiewicza 24, the apartment of my dziadek and babcia. I walked around a lot in that neighborhood as a child with my one year younger sister Carine. I loved just walking around, and as a child you are little and don't get a lot of attention so you can see more. I remember, the streets, the boulevards, the charming cinema, the stare zoo, the bridge over the railway tracks, Fredry, and Stary Rynek.  Twierdza Poznań - fort VII Twierdza Poznań - fort VIII remember a sinister story by my mother or Polish familymember that after the war the abandonned Twierdza Poznań (niem. Festung Posen) was a playground for children, but that it was also a playground or habitat of gigantic rats and that one Polish boy was killed by them. It was a scary story for a kid like me with a vivid imagination. I also remember the scary lynx like large dirty street cats that were outside in the little street behind Mickiewicza 24 where a lot of metal waste containers (Peoples republic era waste containers) stood. These cats were scary and probably dangerous> They did not look normal and didn't behave normal.  Some of them looked like this, like if they had been in fights or were ill Some of them looked like this, like if they had been in fights or were ill  The were huge amounts of Polski Fiat 126p cars in the streets and also Polski Fiat 125p cars and to a lesser extend FSO Polonez cars. Probably the Poles drove in Skoda's, Trabants, Wartburgs and Lada's too? What do you remember Bonobo? The were huge amounts of Polski Fiat 126p cars in the streets and also Polski Fiat 125p cars and to a lesser extend FSO Polonez cars. Probably the Poles drove in Skoda's, Trabants, Wartburgs and Lada's too? What do you remember Bonobo?    Warszawa car, 1962, 1962 Warszawa car, 1962, 1962 Typical Polish seventies and eighties truck I saw a lot in Poznań in 1984 and 1987 Typical Polish seventies and eighties truck I saw a lot in Poznań in 1984 and 1987 |

|

|

|

Post by pjotr on May 25, 2017 3:20:37 GMT 1

Poznań in the seventies   Dąbrowskiego w Poznaniu w 1986 r. Dąbrowskiego w Poznaniu w 1986 r. I remember this Hotel "Orbis Polonez", Poznań - 1984. We had a large family reunion there of Polish family with Polish diaspora branches from the Netherlands (us), the USA (my cousins) and Denmark. It was great that the Poznań and Warsaw family branches were united there with their foreign relatives. These contacts mean a great deal for Polish diaspora members with 100% Polish roots who were born and raised in Poland. Memories and connection to Poland and Polish people never go away. May mother is 84 now and lived in the Netherlands since 1967. She still has Polish phone conversations with Polish friends in Poland and the USA. I remember this Hotel "Orbis Polonez", Poznań - 1984. We had a large family reunion there of Polish family with Polish diaspora branches from the Netherlands (us), the USA (my cousins) and Denmark. It was great that the Poznań and Warsaw family branches were united there with their foreign relatives. These contacts mean a great deal for Polish diaspora members with 100% Polish roots who were born and raised in Poland. Memories and connection to Poland and Polish people never go away. May mother is 84 now and lived in the Netherlands since 1967. She still has Polish phone conversations with Polish friends in Poland and the USA.

|

|

|

|

Post by pjotr on May 25, 2017 3:29:17 GMT 1

|

|

|

|

Post by pjotr on May 25, 2017 3:34:59 GMT 1

|

|

|

|

Post by pjotr on May 25, 2017 3:48:36 GMT 1

|

|

|

|

Post by pjotr on May 25, 2017 4:01:19 GMT 1

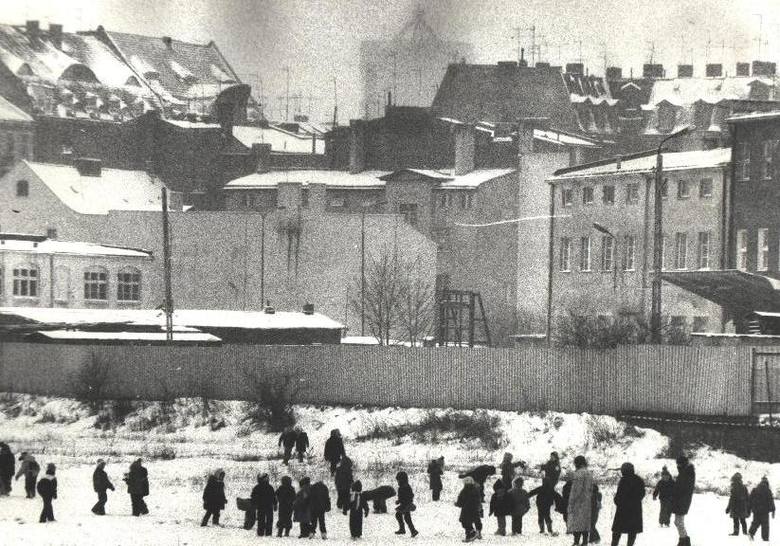

Park Kasprzaka - dziś Wilsona | fot. Stanisław Wiktor, Poznań w 1978 Park Kasprzaka - dziś Wilsona | fot. Stanisław Wiktor, Poznań w 1978  Pupils of a Poznan highschool in the late seventies Pupils of a Poznan highschool in the late seventies   |

|

|

|

Post by pjotr on May 25, 2017 4:36:07 GMT 1

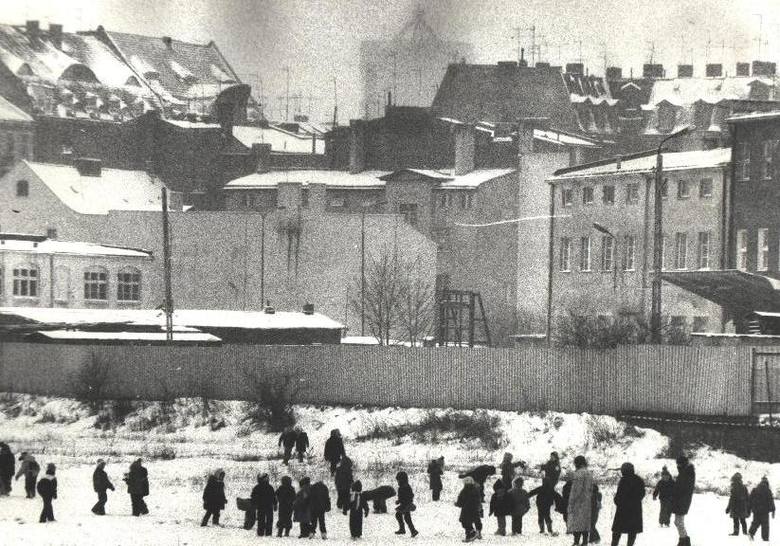

Przed monitorem radiolog dr Janusz Konkiewicz, w tle technik radiologii Jacek Dubas (Fot. Archiwum) Przed monitorem radiolog dr Janusz Konkiewicz, w tle technik radiologii Jacek Dubas (Fot. Archiwum)    Martial law, 1981, Poznań Martial law, 1981, Poznań  What is this, I found it on the internet, but can't understand the meaning of it. Are this ZOMO (Zmotoryzowane Odwody Milicji Obywatelskiej; Motorized Reserves of the Citizens' Militia) in front of these monument for the fallen opposition people of 1956, 1970 and 1976? What is this, I found it on the internet, but can't understand the meaning of it. Are this ZOMO (Zmotoryzowane Odwody Milicji Obywatelskiej; Motorized Reserves of the Citizens' Militia) in front of these monument for the fallen opposition people of 1956, 1970 and 1976?  Poznań girls in 1981 Poznań girls in 1981 Martial law, Poznań 1982, Poland. I have seen a Police force like that in 1984 in Poznań. Martial law, Poznań 1982, Poland. I have seen a Police force like that in 1984 in Poznań.   Poznań, rok 1982 Poznań, rok 1982 Independent demonstration to commemorate the anniversary of the Poznań ~June 1956 uprising Independent demonstration to commemorate the anniversary of the Poznań ~June 1956 uprising Kawalkada milicyjna, róg ul. Fredry i Al. Stalingradzkiej, 1 maja 1983 r. Fot. Jan Kołodziejski. Darowizna – dokumentacja fotograficzna z okresu stanu wojennego w Poznaniu (IPN Po 211/1). Kawalkada milicyjna, róg ul. Fredry i Al. Stalingradzkiej, 1 maja 1983 r. Fot. Jan Kołodziejski. Darowizna – dokumentacja fotograficzna z okresu stanu wojennego w Poznaniu (IPN Po 211/1). Demonstracja społeczna, obok transportery („budy”) ZOMO, ul. Fredry (przed Mostem Teatralnym), 1 maja 1983 r. Fot. Jan Kołodziejski. Darowizna – dokumentacja fotograficzna z okresu stanu wojennego w Poznaniu (IPN Po 211/1). Demonstracja społeczna, obok transportery („budy”) ZOMO, ul. Fredry (przed Mostem Teatralnym), 1 maja 1983 r. Fot. Jan Kołodziejski. Darowizna – dokumentacja fotograficzna z okresu stanu wojennego w Poznaniu (IPN Po 211/1). Teatr niezależny - TEATR - Rok Kultury Niezależnej Teatr niezależny - TEATR - Rok Kultury Niezależnej Poznan train station Poznan train station       Poznań school highschool class 1988 Poznań school highschool class 1988 Poznań 1989 Poznań 1989  |

|

|

|

Post by pjotr on May 25, 2017 4:45:36 GMT 1

Zdjęcie z manifestacji z 15.03.1989 r. na ul. Półwiejskiej w Poznaniu Zdjęcie z manifestacji z 15.03.1989 r. na ul. Półwiejskiej w Poznaniu Niezalezne obchody 1 maja 1989 – Janusz Palubicki, Maciej Musiał, Agnieszka Duczmal – Lepszy Poznań – informacje z Twojego fyrtla Niezalezne obchody 1 maja 1989 – Janusz Palubicki, Maciej Musiał, Agnieszka Duczmal – Lepszy Poznań – informacje z Twojego fyrtla Łóżka i towary z cenami na kilka zer. Poznań w 1989 r. Łóżka i towary z cenami na kilka zer. Poznań w 1989 r. Highschool class Poznań, 1989 Highschool class Poznań, 1989 |

|

|

|

Post by pjotr on May 25, 2017 20:00:43 GMT 1

Dear Jeanne and Bonobo, The wonderful images of Bonobo of Stary Rynek bring flashbacks to my mind of the seventies and eighties. The Old town hasn't changed a lot, maybe it is a little bit cleaner, despite some graffiti on the walls and the fact that these houses are old. Maybe less coal/browncoal, two stroke engine, and heavy communist industry pollution. I remember sitting at a terrace of a Café-Restaurant at Stary Rynek enjoying a Pepsi Cola (you did only have Pepsi Cola in communist Poland for some reason), the horses and the carriages, the relaxed atmosphere, the art galleries, the large buildings in the middle of the old market square, the Poznań Town Hall or Ratusz. That makes the Main Square in the Poznań Old Town different than other other Main squares of old tows which are mostly empty. I remember that my parents bought quite a lof of modern, abstract and realistic graphical art of professional Polish artists from Poznan is some of these galleries, because we had to spend the Zloty's of the inheritance of my Polish grandparents. Due to the quite expensive furniture, crockery, table ware, historical paintings of the German Volksdeutsche Nazi who had left the apartment where they were living in. So my grandparents had been compensated for their loss in Warsaw. In 1987 we went to Orbis state hotels for dinner, I went to a beautiful Polish hairdresser (a Polish brunette). Ofcourse things were equally divided between the family. I am glad that my mother has the Polish Modern art, an old very beautiful oil painting of the Volksdeutsche, which will remind her of my grandparents home in Mickiewicza 24, and some crockery and table ware (Some Polish some Prussian), and the family photo's from Warsaw, Poznań, and Tworki, Skrodzkie near Augustow in Poland. In some of the elements of Stary Rynek I saw similarities with the old market squares of Warsaw and Kraków. And some older streets, houses and courtyards in Kraków also reminded me of Poznań. Maybe there was a typical Polish classicist way of building 16th, 18th, 19th and early 20th century buildings. And the smell of coal and the effect of coal on houses was clear. Maybe there is a general Polish atmosphere and way of laying infrastructure that makes these cities typical Polish. The atmosphere of Prague, Budapest, Vienna, Berlin, Zürich, Paris, Copenhagen, Bruxelles, Ferrières and other European cities I have visited (Rome, Luxemburg, Pizza, Florence, Venice) was quite different. You have a Polishness in streets, boulevards, sings, houses and the people that live in them, walk in and on them. That is what makes a nation too. Back to the old town of Poznań. I also like the old town weighing house (Waga Miejska), behind the Town Hall, facing north, the Saint Stanislaus Church and the various old fountains with their statues. Poznanians really seemed to go to the Old Market square to relax. The rest of the city was more hectic and dynamic.  The Saint Stanislaus Church The Saint Stanislaus Church The interior of the Saint Stanislaus Church The interior of the Saint Stanislaus Church The former Jesuits college is a set of wonderful buildings The former Jesuits college is a set of wonderful buildingsOfcourse as a child I also liked the typical Polish cube like ice wrappend in paper, and all the delicious products of the Bar Mlechny.    Cheers, Pieter |

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on May 27, 2017 20:43:34 GMT 1

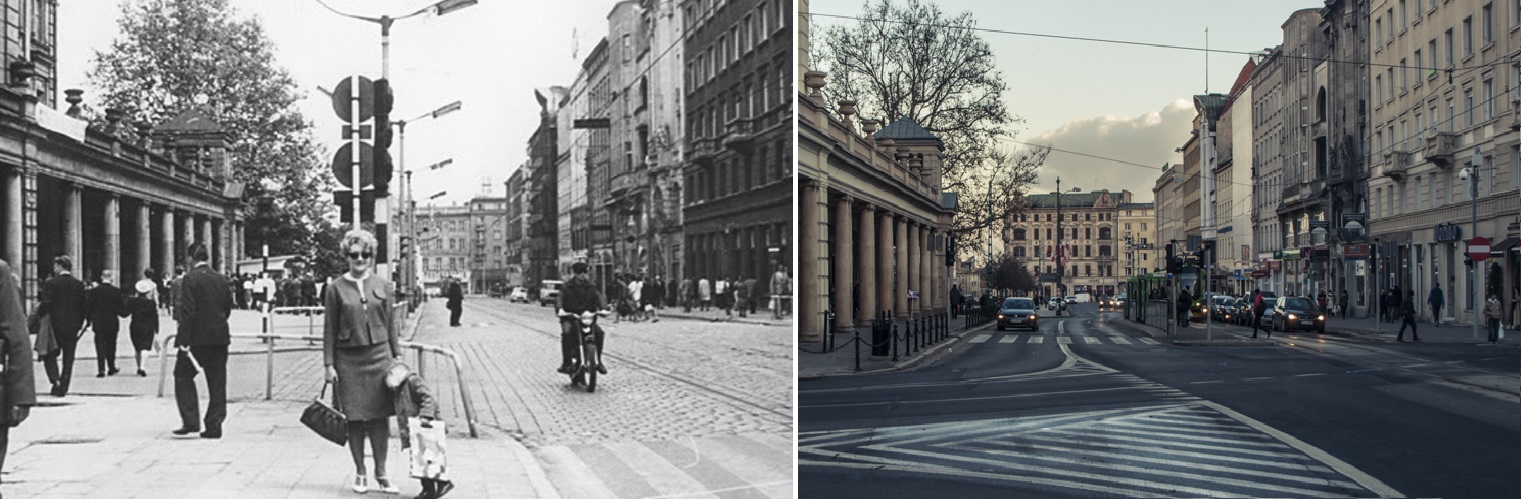

I remember the city as a child and teenager (14 and 17 years old, I visited the city in 1984 and 1987), and have very good, sentimental, romantic and thus sweet memories about the city, One of the pictures you posted almost perfectly matches the one I took 8 years ago and which I later dubbed my favourite photo from Poznań due to the mixture of architectonic styles.   |

|

|

|

Post by pjotr on May 28, 2017 10:57:10 GMT 1

I remember the city as a child and teenager (14 and 17 years old, I visited the city in 1984 and 1987), and have very good, sentimental, romantic and thus sweet memories about the city, One of the pictures you posted almost perfectly matches the one I took 8 years ago and which I later dubbed my favourite photo from Poznań due to the mixture of architectonic styles.   It is great to see your inage next to the old one from the Polish Peoples Republic era. To be honest I like your inage better, because I see more buildings in the distande and rhe large modern building on the left looks more clean and nice than in the Peoples Republic era. |

|

|

|

Post by pjotr on May 28, 2017 10:59:18 GMT 1

The building also has an nicer new roof with orange roof material. It is nicer than the old grey roof.

|

|

|

|

Post by jeanne on May 28, 2017 12:07:54 GMT 1

Pieter,

You have "published" a wonderful "book" here with these posts! So much information! It is taking me quite awhile to read through it and examine all the photos...I can only do a bit at a time, but I want you to know that I am enjoying it all! Now you are giving me one of those "windows to Poland" that I so love. Thank you!

|

|

|

|

Post by pjotr on May 28, 2017 14:10:42 GMT 1

Dear Jeanne and Bonobo,

Since Bo created this thread with my contribution to my melancholic connection and memories of Poznań. Read, not nostalgic but melancholic. I don't want to go back or long for Poznań of the Communist Polish Peoples Republic, but love the memories about my grandparents, uncles, aunts, cousins and friends of my mom and the city that was present then with the medieval, Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, Renaissance, Baroc/Rococo, enlightenment, Prussian, Interbellum (1919-1939), Second World War and Polish Peoples Republic element (the communist socialist architecture)elements of it. I post here some images I made from family albums I watched in my parents home this weekend.

Cheers,

Pieter

|

|

|

|

Post by pjotr on May 28, 2017 15:17:37 GMT 1

My sister Carine and I in 1984 in Poznan.  Poznan, 1984, the monument for 1956, 1970, 1976 and 1980  Mickiewicza 24, Poznan, photo by my then 16 year old sister Carine  Roman-Catholic Marriage in a Roman Catholic church in Poznan in 1967    My dziadek Josef Kotowicz with Polish uncles and aunts of mine in my grandparents apartment in Mickiewicza 24 in PoznanMariage telegram from Poland for my mother My dziadek Josef Kotowicz with Polish uncles and aunts of mine in my grandparents apartment in Mickiewicza 24 in PoznanMariage telegram from Poland for my mother   A familygathering with Polish familymembers and my parents. My parents are the only ones alive today. A familygathering with Polish familymembers and my parents. My parents are the only ones alive today. Familygathering of Poznan, Warsaw and Dutch familymembers of the Kotowicz, Pantoflinksy, Kalinowski and probably Kwasieborski and Pluijgers-Kodde branches? Familygathering of Poznan, Warsaw and Dutch familymembers of the Kotowicz, Pantoflinksy, Kalinowski and probably Kwasieborski and Pluijgers-Kodde branches? My Dutch grandmother and my Polish grandfather. I like this photo very much. Two very nice, sophisticated, gentle, humble human beings.A generation of very fine and good people that doesn't exist anymore. People who knew several languages. My dziadek spoke Polish, Russian, German, and my grandmother spoke and read Dutch, French, English and German. I have had some very excellent French lessons as a teenager from her. I had a very strong bond with both my Dutch grandmother and my babcia (Polish grandmother). Both had a particular sense of humor and very strong and nice characters and personalities. My Dutch grandmother and my Polish grandfather. I like this photo very much. Two very nice, sophisticated, gentle, humble human beings.A generation of very fine and good people that doesn't exist anymore. People who knew several languages. My dziadek spoke Polish, Russian, German, and my grandmother spoke and read Dutch, French, English and German. I have had some very excellent French lessons as a teenager from her. I had a very strong bond with both my Dutch grandmother and my babcia (Polish grandmother). Both had a particular sense of humor and very strong and nice characters and personalities. Anja Kalinowska, the woman with the dark glasses, third from the left, is the mother of Joanna Kalinowska, my cousin from Poznan. Anja Kalinowska, the woman with the dark glasses, third from the left, is the mother of Joanna Kalinowska, my cousin from Poznan. |

|

|

|

Post by pjotr on May 28, 2017 18:35:03 GMT 1

It is the same room in Mickiewicza 24, but about two decades later. From the sixties to the eighties. This could be 1984, or 1985, 1986, 1987? I like this photo very much, because you have younger and older familymembers from Poznań and the USA united in one photo. Unique material because some aren't alive anymore. I see my cousins Joanna from Poznan and Mary from the USA. And next to them my babcia and her brother uncle Janek. The guy in the right corner with the little girl (the sister of Joanna, who sits in the left corner) is the Polish theatre and movie actor Wojciech Kalinowski, father of Joanna and her little sister. I remember that he took us to the empty, but magnificent and beautiful Poznan theater and shouted in the empty theatre ' To be or not to be that is the question'. Janek the thrid from the left is the grandfather of Joanna and her sister and the father of Anja the mother of Anja and her sister. The young woman in the middle was back then Mary Kwasieborski and today Mary Kazmierczak, my American cousin from Chicago, part of the Polish American family. She is sister and daughter of my American aunt Maryshia Rybak (before that Maryshia Kwasieborski). Maryshia was my mothers older sister and as a child and young woman was called Maryshia Kotowicz. My Babcia is the third person from the right.  Wojciech Kalinowski today Wojciech Kalinowski today

|

|

|

|

Post by pjotr on May 28, 2017 21:54:19 GMT 1

Pieter, You have "published" a wonderful "book" here with these posts! So much information! It is taking me quite awhile to read through it and examine all the photos...I can only do a bit at a time, but I want you to know that I am enjoying it all! Now you are giving me one of those "windows to Poland" that I so love. Thank you! Dear Jeanne, I realise that a few of the people of the Polish Diaspora have the chance to connect to Polish family in Poland and with Poland. I know people of the Polish Diaspora in the Netherlands who have never been in Poland. In America many people with Polish heritage lost connection to their Polish ancesters, because they didn't know where there Polish American ancesters came from, they don't speak Polish and therefor have a distance to Poland. This 'Window to Poland' was given to me by my parents who travelled with us by train and car to Poland and gave us kids a chance to relate to the country of my mothers birth and start of life. Poland was so radical different than our Western-European, democratic and Capitalist country, that it was a slight culture shock. Completely different language, completely different culture, completely different society, people, traditions, customs, standard of living, economy, family, social attitudes, cities, towns, villages, hamlets, Urban agglomerations, infrastructure and technology. Some things were extremely old fashionate and outdated, but that gave Poznań it's shabby charm, it's melancholic atmosphere (like the past was preserved)and humanity. For instance the contrast between the official state economy, society and socialist order and the secret societies of social networks of families, friends and colleages which were by no means communist. A huge black market economy existed next to the official one. You had a vibrant Samizdat (underground) press, dissident movements and dissident culture. Ofcourse I didn't see the latter, but it was there. Cheers, Pieter |

|

|

|

Post by jeanne on May 29, 2017 1:18:58 GMT 1

I realise that a few of the people of the Polish Diaspora have the chance to connect to Polish family in Poland and with Poland. I know people of the Polish Diaspora in the Netherlands who have never been in Poland. In America many people with Polish heritage lost connection to their Polish ancesters, because they didn't know where there Polish American ancesters came from, they don't speak Polish and therefor have a distance to Poland. My grandfather immigrated on his own when he was sixteen...I think I have mentioned how he was smuggled out of Poland in a barrel to avoid the Russians who were drafting young men into the military. He stayed in touch with his family in Poland until WWII, then communication ceased...who knows what happened to them...this is one thing I would like to find out, but I don't hold much hope of doing so. You are so fortunate, Pieter, to have these experiences as part of your life and personal education! Thank you for sharing them with us. This is the kind of history I love the best, to learn of how ordinary people lived and what life was like for them. |

|

|

|

Post by pjotr on May 31, 2017 23:10:08 GMT 1

Jeanne,

Your grandfather was a brave, adventerous and maybe smart man. Due to his escape from Poland he escaped from the First World War (he probably wouldn't have survived) and avoided the poverty of the crisis years of the late twenties and thirties in Poland (decades after his escape), the Nazi terror in Second World War Poland, and Stalinism and Polish communism after the war.

You were able to have your good life in the North-East of the USA, built a life with your American husband and kids, work and be active for the American Roman-Catholic church. My mother told me past weekend that I have been more often as a kid in Poznań than I realized. Also as young kinds in the early seventies. Ofcourse I can't remember that. I remember the cosy very social Polish family life. The Polish Roman-Catholic church. My Polish grandmother (Babcia) was a very spiritual and religious person. She went nearly her entire life to the Roman-Catholic church on sunday, and often on weekdays some tuesday mornings and some evening services. Old fashionate Catholic, a sort of Catholicism you seldom see in the West nowadays. Faith helped her through the war days and also through difficult times during communism.

I remember the familyculture of my Polish grandparents and the Polish uncles, aunts, cousins and friends that visited them. I remember their neighbours in Mickiewicza 24. One old fragile, aristocratic lady with Magnate background, a countess, duchess or Barones ( Magnates were a social class of wealthy and influential nobility in the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland and Grand Duchy of Lithuania (and later the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth), see Magnates of Poland and Lithuania ). She had a hard time surviving in a Poland in which a proletarian and peasant class ruled. (The nomenklatura of the Polish United Workers' Party, PZPR.) Having lost all their possessions, class position (in Pre-war Sanation -Sanacja- Poland), wealth and meaning of life. The old aristocratic lady spoke French next to Polish. On the other side there were very nice people from a humble background. The man was a tram driver. People had little space for themselves, and not much financial means due to communist Poland which prohibited private initiative. One guy in the building was a nasty, scary character, quite insane, abnormal, blunt (rude) and vicious. Anti-semitic, hostile to his neighbours (my grandparents and the poor old aristocratic lady and her husband). Sometimes the atmosphere for us kids was so surreal, nearly pre-war, in it's old fashioned, dated, situation, that it was like a dream or an old twenties, thirties or forties movie.

I think people survived these grey, dull and boring communist years due to the fact that there was a strong family life, a social cultural network of friends and (non-communist) colleagues or student time friends. The Roman-Catholic church played an important role for some and a slightly less important role for others. You also had secular-humanist and atheist dissidents. Despite communism, spying on them by the Służba Bezpieczeństwa (the Polish communist secret service) and some social pressure from the state and communist party, many people had connections and relations with the Polish Diaspora abroad. (For instance the American, Danish and Dutch family branches in the case of my family). Some non communist Poles still held important positions as doctors, surgeons, scientists, architects, theatre actors/actresses, artists, musicians, administrators, teachers and professors.

Cheers,

Pieter

|

|

|

|

Post by pjotr on Jun 1, 2017 22:13:16 GMT 1

Jaga encouraged me to post these pictures and his memories on her Forum too, since it is obvious how much it matters to me and it reminds her of her time in time in Kraków in Poland when somehow she had more time to be just with family members.

Jaga was in Poznan only once. She remembered that it looked like a commercial center of Poland. Its center was quite grandiose. It was hot, the middle of summer, they went to see many churches, since her dad was a history professor and they found some shade there.

She did not see Poznan as overly German. Jaga actually liked some multi-cultural, especially German atmosphere. Whenever she goes to Katowice, she likes its specific Silesian atmosphere, which is full of German history.... She likes Polish-German foods and traditions, which she missed in Krakow.

|

|

|

|

Post by pjotr on Jun 1, 2017 22:55:38 GMT 1

Karl thanked me for your sharing my Polish family life. It sure may look like a book story, movie or documentary (Reportaż) which in fact in a way it is. Butut Karl is right, this is not a book, not fiction, but the reality of living people that are my family. Most of them not alive anymore, but alive in memories. I share this info and images, becsuse that is what I can do on these Forums. That is my information, knowledge and experience with Poland.

My mother says that I know more about present day Poland than she does and that she probably would be alienated if she went to Poland today. Completely new generations, new Polish words, new Polish sentences, new Polish expressions and sayings, partly or completely changed cities and towns. A different vocabulary. Different press and media, new neighbourhoods, new city centers, new infrastructure and probably the people of her time are gone.

The together photo of my sister Carin and myself I indeed is one of the corner stones of memories for me. We were a tight knit family and wherever we went my sister and I were playing partners and buddies. In Zeeland, on holidays to my Dutch grandmother in the Middle-eastern part of the Netherlands, the Veluwe, in the Belgian Ardennes mountains and indeed in Germany on our way to Poland and in Poland during these holidays.

I remember going out to a discotheque in back then still communist Poland in the large Prussian heavy castle in the Poznan city center. A typical eighties disco with a sort of Polish version of Italian disco style pop music and dance music. I loved the atmosphere, the Polish girls and young women, who were better dress back then than the Dutch ladies. The terrible era of thick pumped up hair, coolcat clothes, not a feminine look. The Polish girls had elegant dresses and min skirts.

Due to the fact that I had to watch over my one year younger sister who was 16 and the fact that my sister was hanging on me I didn't managed to contact Polish girls as much as I would do in the Netherlands. I the Netherlands I started going out at the age of 16 (we didn't had the alcohol and going at age limit the USA has back then). But we enjoyed the evening, just enjoying the atmosphere, some innocent drinks (Pepsi cola, some fruit drink and maybe that I drank one beer). It was really a great experience. The people really escaped the daily life by going out in the weekend.

Later that holiday I liked just walking around in the evening and tasting the atmosphere of the Poznan night life next to the day life I experience during the day. People enjoyed walking around, visiting friends and family in the evenings and weekends and having social lives. That social life was important, because the communist plan economy (collectivism), lack of political and cultural freedom limited people. So they managed their own lives with their daily jobs, their family lives, their social lives with friends and all their activities in which the communist party wasn't involved. Some people went to church only on sunday, some also on Saturday evening, tuesday morning, and in the evening during weekdays. You had many sorts of Roman-Catholicism. From very orthodox nearly fundamentalist strict people, to common conservatives or traditionals, average Roman-Catholics, custom (culture) catholics, secular catholics, catholic intelligentsia and a broad spectrum of Roman-Catholic clergy and professionals. The Roman-Catholic church was special and I especially liked the masses in the church of the Benedictine monks we went to. They sang wonderful and the church was always full. There were so much people that we sometimes stood outside during mass. There was a great strength, great spirit, great comfort, great consolation in the Roman-Catholic faith and the Roman-Catholic church back then. I couldn't understand Polish, but I felt the spiritual strength in the mass preaching of the priests and in the singing of the monks and the Poznan people. Very, very special. It was a beautiful Baroque church too.

The photo of my Dutch Grand mother and Polish Grand father is another precious photo to cherish for all time. Karl is right in saying that.

When Karl looked at all these photosform him it was as if peeking through a hidden window in to some one else life and as a time of discovery of a different time and of course a different place. He is right that is exactly what this thread is. My memory, and sharing a time what once was, because most of these people on that old black and white photo's passed away. But their life was not in vain. They had a great, warm, special, cosy, traditional, Polish family life with a lot of family gatherings and shared dinners, lunches, family gatherings and etc. My babcia (Polish grandmother) was a great cook and loved to cook. A dinner at her home was a dinner with many courses; appetizer, followed by a variety of dishes, a salad course or a delicious soup, the main dish and dessert. She was good in the traditional Polish cuisine to next to the general European (French) cuisine. She was excellent in preparing game food or fish. Her Polish pastries were the most delicious you can imagine. Easter pastries, but also very delicious cakes and especially her Polish Cheesecake was very, very good. I liked and loved the Bar Mlechny, but my babcia was a great alternative for the Bar Mlechny. (the Milk bar)

Indeed I am very fortunate to have had such wonderful family members and still having my parents, sister, Polish American cousins and Polish cousin.

I share these things, because that is what I can share. I have to go back to Poland to gain more knowledge, experience and connection with today's Modern Poland.

Cheers,

Pieter

|

|

|

|

Post by pjotr on Jun 1, 2017 22:56:39 GMT 1

German history of Poznań In the second half of the 17th century and most of the 18th, Poznań was severely affected by a series of wars (and attendant military occupations, lootings and destruction) – the Second and Third Northern Wars, the War of the Polish Succession, the Seven Years' War and the Bar Confederation rebellion. It was also hit by frequent outbreaks of plague, and by floods, particularly that of 1736, which destroyed most of the suburban buildings. The population of the conurbation declined (from 20,000 around 1600 to 6,000 around 1730), and Bambergian and Dutch settlers (Bambrzy and Olędrzy) were brought in to rebuild the devastated suburbs. In 1778 a " Committee of Good Order" (Komisja Dobrego Porządku) was established in the city, which oversaw rebuilding efforts and reorganised the city's administration. However, in 1793, in the Second Partition of Poland, Poznań, came under the control of the Kingdom of Prussia, becoming part of (and initially the seat of) the province of South Prussia. I quote Encyclopedia Britannica:In 1793 Poznań was annexed to Prussia, intensifying a Germanization that had begun as early as the 13th century, with the arrival of the first German immigrants. From 1807 to 1815 the city was a part of the Grand Duchy of Warsaw, then reverted to Prussian control. Anti-Polish and anti-Catholic measures were enacted by German chancellor Otto von Bismarck in the 1870s. In 1886 a commission of colonization was organized to buy Polish land for German colonists, but the Poles established cooperative credit organizations and continued to defeat Prussian efforts to control Poznań. At the beginning of the 20th century much building was done to give the city a Prussian complexion, and Poznań was renamed Posen.

Meanwhile, Poznań progressed economically, with its population tripling between 1871 and 1910, and in 1918 its citizens defeated their Prussian overseers. Poznań prospered somewhat between the two world wars, but, with the return of the Germans in 1939, the city was devastated; its inhabitants were deported or exterminated. Russian forces defeated the Germans during the siege of 1945, leaving the city in ruins. Poznań was rebuilt after World War II and has become the administrative, industrial, and cultural centre of western Poland. As one of Poland’s largest industrial centres, Poznań has varied industry that includes metallurgical works; textile mills; clothing and food-, metal-, and rubber-processing plants; chemical facilities; and an automobile factory. Since 1921 it has been the site of a major international trade fair. The Prussian authorities expanded the city boundaries, making the walled city and its closest suburbs into a single administrative unit. Left-bank suburbs were incorporated in 1797, and Ostrów Tumski, Chwaliszewo, Śródka, Ostrówek and Łacina (St. Roch) in 1800. The old city walls were taken down in the early 19th century, and major development took place to the west of the old city, with many of the main streets of today's city centre being laid out. In the Greater Poland Uprising of 1806, Polish soldiers and civilian volunteers assisted the efforts of Napoleon by driving out Prussian forces from the region. The city became a part of the Duchy of Warsaw in 1807, and was the seat of Poznań Department – a unit of administrative division and local government. However, in 1815, following the Congress of Vienna, the region was returned to Prussia, and Poznań became the capital of the semi-autonomous Grand Duchy of Posen.  The city continued to expand, and various projects were funded by Polish philanthropists, such as the Raczyński Library and the Bazar hotel. The city's first railway, running to Stargard, opened in 1848. Due to its strategic location, the Prussian authorities intended to make Poznań into a fortress city, building a ring of defensive fortifications around it. Work began on the citadel ( Fort Winiary) in 1828, and in subsequent years the entire set of defences ( Festung Posen) was completed.  A Greater Poland Uprising during the Revolutions of 1848 was ultimately unsuccessful, and the Grand Duchy lost its remaining autonomy, Poznań becoming simply the capital of the Prussian Province of Posen. It would become part of the German Empire with the unification of German states in 1871. Polish patriots continued to form societies (such as the Central Economic Society for the Grand Duchy of Poznań), and a Polish theatre (Teatr Polski, still functioning) opened in 1875; however the authorities made efforts to Germanize the region, particularly through the Prussian Settlement Commission (founded 1886). Germans accounted for 38% of the city's population in 1867, though this percentage would later decline somewhat, particularly after the region returned to Poland.  Another expansion of Festung Posen was planned, with an outer ring of more widely spaced forts around the perimeter of the city. Building of the first nine forts began in 1876, and nine intermediate forts were built from 1887. The inner ring of fortifications was now considered obsolete and came to be mostly taken down by the early 20th century (although the citadel remained in use). This made space for further civilian construction, particularly the Imperial Palace ( Zamek), completed 1910, and other grand buildings around it (including today's central university buildings and the opera house). The city's boundaries were also significantly extended to take in former suburban villages: Piotrowo and Berdychowo in 1896, Łazarz, Górczyn, Jeżyce and Wilda in 1900, and Sołacz in 1907.  At the end of World War I, the final Greater Poland Uprising (1918–1919) brought Poznań and most of the region back to newly reborn Poland, which was confirmed by the Treaty of Versailles. The local German populace had to acquire Polish citizenship or leave the country. This led to a great migration of the ethnic German settlers, whose numbers decreased from 65,321 in 1910 to 5,980 in 1926 and further to 4,387 in 1934.  Sources Sources: Wikipedia and Encyclopedia Britannica

|

|

|

|

Post by pjotr on Feb 28, 2020 5:24:27 GMT 1

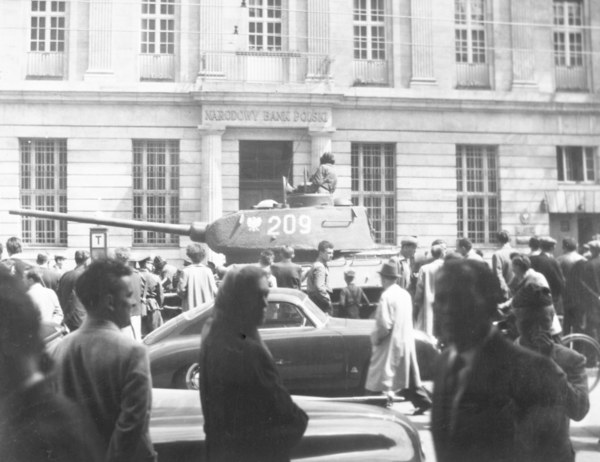

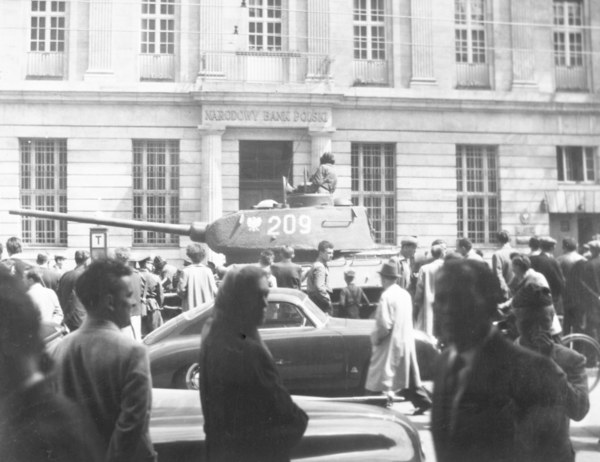

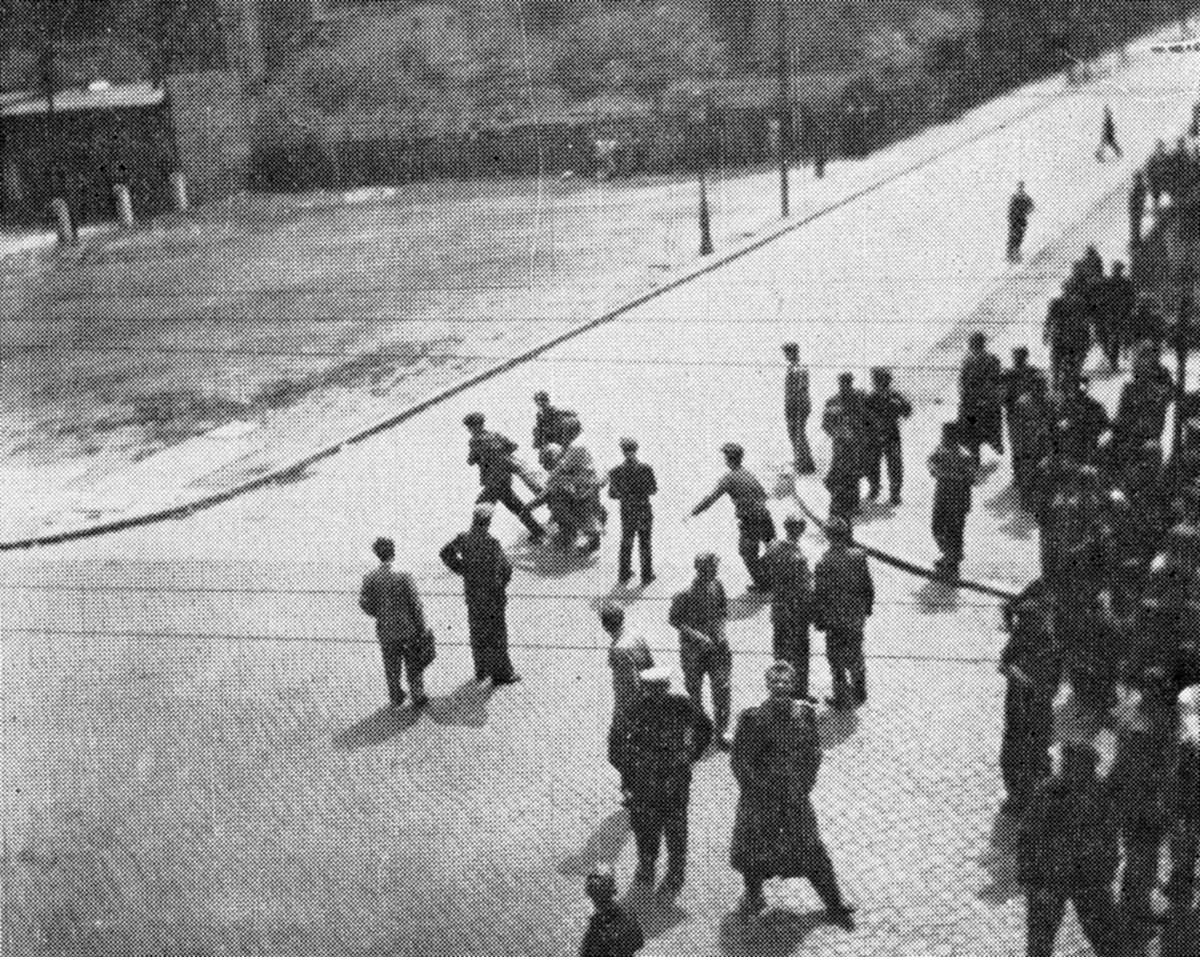

Poznań 1945-1989 Poznań during the late forties Poznań during the late forties Poznań 1949 Poznań 1949 Poznań 1949 Poznań 1949 Poznań 1950 Poznań 1950 Poznań 1950 Poznań 1950 Poznań 1945, widoczny budynek to nieistniejące już kino “Bałtyk” – w obecnie w tym miejscu przy Rondzie Kaponiera trwa budowa nowoczesnego biurowca Poznań 1945, widoczny budynek to nieistniejące już kino “Bałtyk” – w obecnie w tym miejscu przy Rondzie Kaponiera trwa budowa nowoczesnego biurowca Poznań 1956 Poznań 1956 Poznań 1956 Poznań 1956 Poznań 1956My grandparents in Poznań said that there were army tanks in their street ulica Mickiewicza Adama. There were violent clashes and people threw a molotov cocktail at the tank, burning the tank and killing the tank crew. Poznań 1956My grandparents in Poznań said that there were army tanks in their street ulica Mickiewicza Adama. There were violent clashes and people threw a molotov cocktail at the tank, burning the tank and killing the tank crew.

The Poznań protests of 1956, also known as Poznań June (Polish: Poznański Czerwiec), were the first of several massive protests against the communist government of the Polish People's Republic. Demonstrations by workers demanding better working conditions began on 28 June 1956 at Poznań's Cegielski Factories and were met with violent repression.

A crowd of approximately 100,000 people gathered in the city centre near the local Ministry of Public Security building. About 400 tanks and 10,000 soldiers of the Polish People's Army and the Internal Security Corps under Polish-Soviet general Stanislav Poplavsky were ordered to suppress the demonstration and during the pacification fired at the protesting civilians.