Post by Bonobo on Jun 15, 2017 20:20:16 GMT 1

Interesting article explains why east sides of many cities are poorer than west sides.

www.theguardian.com/cities/2017/may/12/blowing-wind-cities-poor-east-ends

Blowing in the wind: why do so many cities have poor east ends?

From London to Paris, New York to Helsinki, poverty tends to cluster in the east. One study suggests a surprising reason why

1st December 1912: A street in London’s East End.

A street in London’s East End in 1912. Photograph: Topical Press Agency/Getty Images

Cities is supported by

Rockefeller Foundation

About this content

Leo Benedictus

Friday 12 May 2017 07.15 BST

Last modified on Thursday 15 June 2017 16.53 BST

The question is so obvious that you could easily forget to ask it: why do cities so often have a poor east side? To be clear, the mystery is not why every city has its leafy and its grubby sections – it costs money to live in nice places and to avoid nasty ones, which tends to group people into them by wealth. The mystery is why the poor groups always end up in the east.

Of course, the true picture is never neat nor simple, but by common consent a British-biased list of cities with poor eastern districts would include: London, Paris, New York, Toronto, Bristol, Manchester, Brighton and Hove, Oxford, Glasgow, Helsinki and Casablanca. No doubt there are some cities where poverty clusters in the west, but they seem harder to find; perhaps Delhi and Sydney?

The story seems easier to explain case by case. In London, for example, the docks are downstream in the east, and docks are rarely very salubrious in cities. For much of its history, the Thames also took the city’s waste, and smell, eastward. No wonder the poor wound up living there, you might say.

But then consider Paris, where the Seine flows westward, as does the Avon in Bristol. Or New York, which effectively has two rivers, and is a completely different shape. Or even Brighton, which has no rivers at all. Despite their differences, the story never varies: for poverty, look east.

One theory is that it’s all about air pollution. In the middle latitudes where most of the world’s cities can be found, the prevailing winds are westerlies, which means they blow to the east. Crudely, it has long been thought that they might take smoke and odours with them, and now a new study by Stephan Heblich, Alex Trew and Yanos Zylberberg for the Spatial Economics Research Centre suggests this theory might be right.

“This anecdotal discussion about pollution in the centre of cities and smoke drifting to the east is something that we have been documenting very precisely,” Zylberberg tells me. “Basically what we’ve been seeing in the past, because of pollution and wind patterns, is rich people escaping the eastern parts of town, because they were very polluted.”

For their research, published last November, Zylberberg and his colleagues built simulations of 70 British cities, including the sites of 5,000 industrial chimneys, as they would have been in 1880. Using mathematical models they claim to have been able to reconstruct the movement of air within the given topography and work out where the pollution would end up. They concluded that areas of high pollution were indeed more likely to become deprived areas, and found that they were generally in the east.

What we’ve been seeing in the past is rich people escaping the eastern parts of town, because they were very polluted

“Past pollution explains up to 20% of the observed neighbourhood segregation whether captured by the shares of blue collar workers and employees, house prices or official deprivation indices,” the paper says. It concluded that no British cities have wind patterns which ought to create a polluted west. Heblich, Trew and Zylberberg also looked for eastern poverty patterns before the industrialisation of the 19th century, and did not find them.

A little more here

spatial-economics.blogspot.com/2017/05/east-side-story-historical-pollution.html

The previous result leaves one question unanswered. How could sorting caused by 1880 pollution be visible nowadays almost 100 years after the 1926 Smoke Abatement Act and 50 years after the Clean Air Acts (which quickly and considerably reduced the extent of coal-based pollution within cities)? While the average correlation between (past) air pollution and the share of low-skilled workers is almost as large as before in 2011, this observation masks important differences. In neighbourhoods where past pollution levels were close to the city average (either slightly lower or higher), social segregation disappeared between the Clean Air Acts and today. For instance, cities with low overall levels of pollution, where all neighbourhoods were close to the city average, do not display any West-East differences in outcomes today. By contrast, neighbourhoods where past pollution was well above or well below the city average (mostly present in cities with high average pollution) are locked in their historical equilibrium. These non-linearities in the persistence of neighbourhood composition are shown in Figure 1. This illustrates the existence of ‘tipping dynamics’: past a certain threshold, a poor neighbourhood repels richer residents even when the original disamenity has long waned. While it is beyond the scope of our project to identify the main channels at play, we present indicative evidence that this might be related to (the lack of) work opportunities, school composition (Free-Meal pupils), crime incidence or the quality of the housing stock.

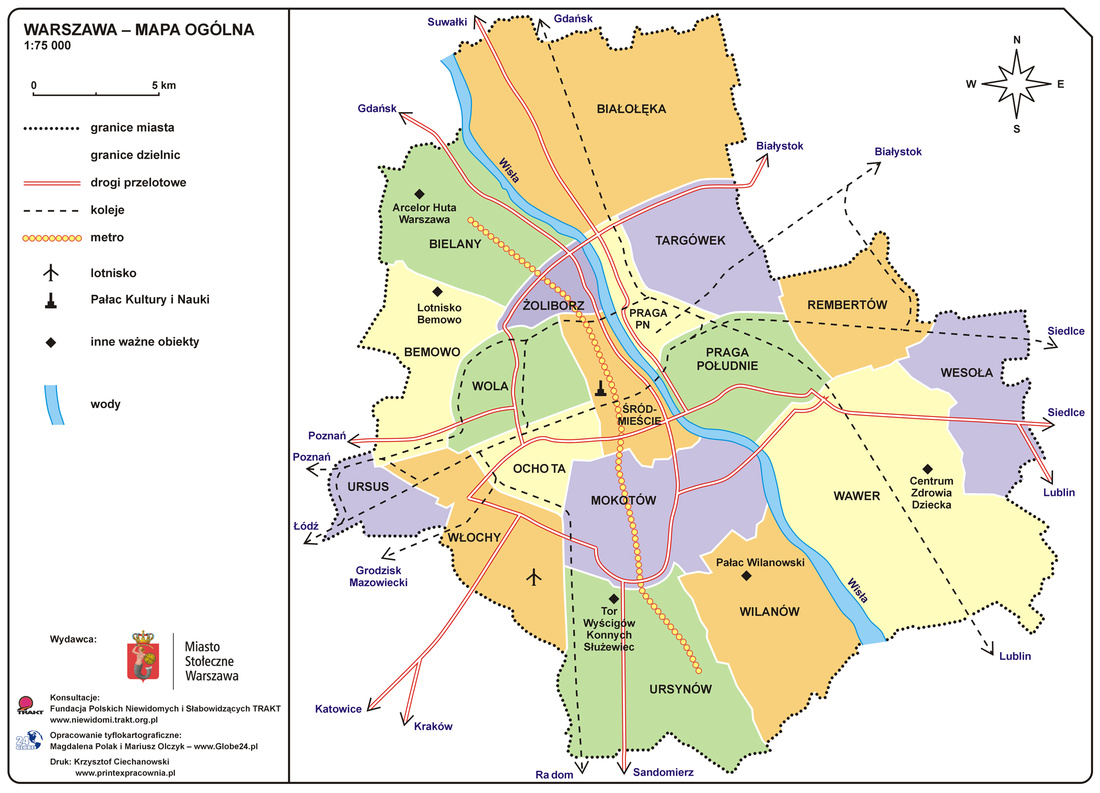

Warsaw

- Praga district on east side of the river

www.warszawacity.com/zdjecia-praga-polnoc,fotografie,zdjecia-warszawy.html

West side

www.theguardian.com/cities/2017/may/12/blowing-wind-cities-poor-east-ends

Blowing in the wind: why do so many cities have poor east ends?

From London to Paris, New York to Helsinki, poverty tends to cluster in the east. One study suggests a surprising reason why

1st December 1912: A street in London’s East End.

A street in London’s East End in 1912. Photograph: Topical Press Agency/Getty Images

Cities is supported by

Rockefeller Foundation

About this content

Leo Benedictus

Friday 12 May 2017 07.15 BST

Last modified on Thursday 15 June 2017 16.53 BST

The question is so obvious that you could easily forget to ask it: why do cities so often have a poor east side? To be clear, the mystery is not why every city has its leafy and its grubby sections – it costs money to live in nice places and to avoid nasty ones, which tends to group people into them by wealth. The mystery is why the poor groups always end up in the east.

Of course, the true picture is never neat nor simple, but by common consent a British-biased list of cities with poor eastern districts would include: London, Paris, New York, Toronto, Bristol, Manchester, Brighton and Hove, Oxford, Glasgow, Helsinki and Casablanca. No doubt there are some cities where poverty clusters in the west, but they seem harder to find; perhaps Delhi and Sydney?

The story seems easier to explain case by case. In London, for example, the docks are downstream in the east, and docks are rarely very salubrious in cities. For much of its history, the Thames also took the city’s waste, and smell, eastward. No wonder the poor wound up living there, you might say.

But then consider Paris, where the Seine flows westward, as does the Avon in Bristol. Or New York, which effectively has two rivers, and is a completely different shape. Or even Brighton, which has no rivers at all. Despite their differences, the story never varies: for poverty, look east.

One theory is that it’s all about air pollution. In the middle latitudes where most of the world’s cities can be found, the prevailing winds are westerlies, which means they blow to the east. Crudely, it has long been thought that they might take smoke and odours with them, and now a new study by Stephan Heblich, Alex Trew and Yanos Zylberberg for the Spatial Economics Research Centre suggests this theory might be right.

“This anecdotal discussion about pollution in the centre of cities and smoke drifting to the east is something that we have been documenting very precisely,” Zylberberg tells me. “Basically what we’ve been seeing in the past, because of pollution and wind patterns, is rich people escaping the eastern parts of town, because they were very polluted.”

For their research, published last November, Zylberberg and his colleagues built simulations of 70 British cities, including the sites of 5,000 industrial chimneys, as they would have been in 1880. Using mathematical models they claim to have been able to reconstruct the movement of air within the given topography and work out where the pollution would end up. They concluded that areas of high pollution were indeed more likely to become deprived areas, and found that they were generally in the east.

What we’ve been seeing in the past is rich people escaping the eastern parts of town, because they were very polluted

“Past pollution explains up to 20% of the observed neighbourhood segregation whether captured by the shares of blue collar workers and employees, house prices or official deprivation indices,” the paper says. It concluded that no British cities have wind patterns which ought to create a polluted west. Heblich, Trew and Zylberberg also looked for eastern poverty patterns before the industrialisation of the 19th century, and did not find them.

A little more here

spatial-economics.blogspot.com/2017/05/east-side-story-historical-pollution.html

The previous result leaves one question unanswered. How could sorting caused by 1880 pollution be visible nowadays almost 100 years after the 1926 Smoke Abatement Act and 50 years after the Clean Air Acts (which quickly and considerably reduced the extent of coal-based pollution within cities)? While the average correlation between (past) air pollution and the share of low-skilled workers is almost as large as before in 2011, this observation masks important differences. In neighbourhoods where past pollution levels were close to the city average (either slightly lower or higher), social segregation disappeared between the Clean Air Acts and today. For instance, cities with low overall levels of pollution, where all neighbourhoods were close to the city average, do not display any West-East differences in outcomes today. By contrast, neighbourhoods where past pollution was well above or well below the city average (mostly present in cities with high average pollution) are locked in their historical equilibrium. These non-linearities in the persistence of neighbourhood composition are shown in Figure 1. This illustrates the existence of ‘tipping dynamics’: past a certain threshold, a poor neighbourhood repels richer residents even when the original disamenity has long waned. While it is beyond the scope of our project to identify the main channels at play, we present indicative evidence that this might be related to (the lack of) work opportunities, school composition (Free-Meal pupils), crime incidence or the quality of the housing stock.

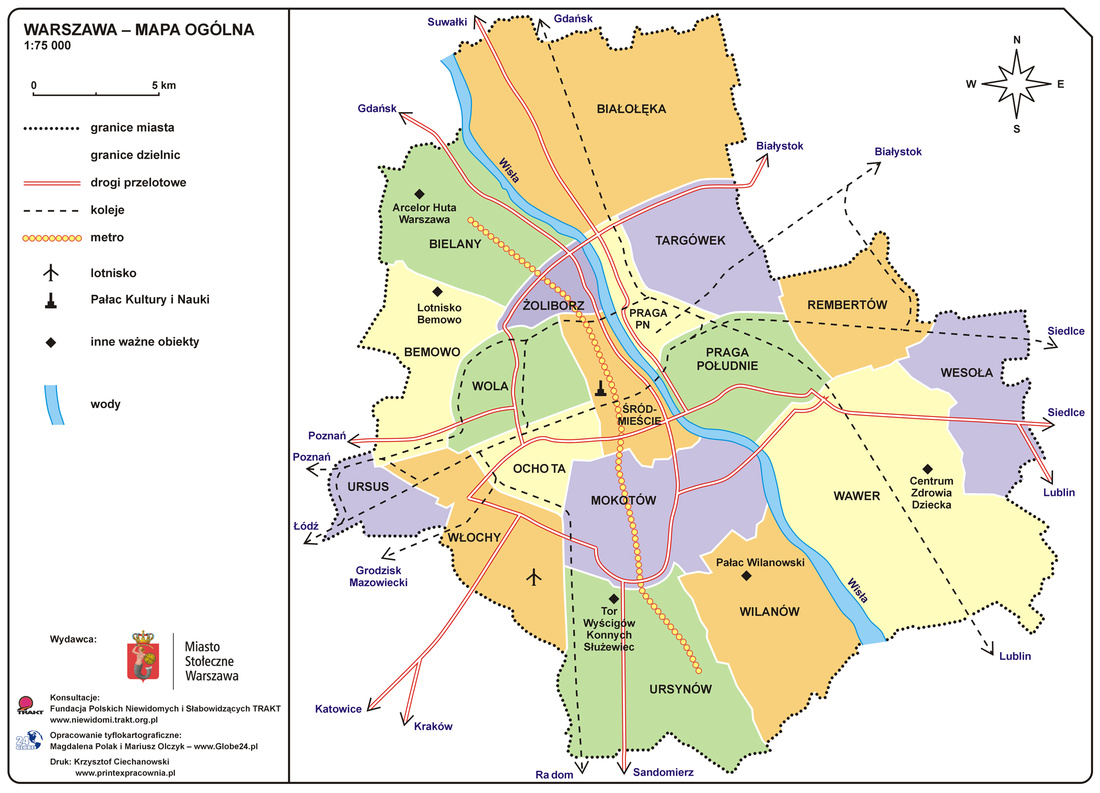

Warsaw

- Praga district on east side of the river

www.warszawacity.com/zdjecia-praga-polnoc,fotografie,zdjecia-warszawy.html

West side