Dear Bonobo and Jeanne,

I saw a very good report about

Catalonia in the Dutch Sundaymorning Intelligentsia newsprogram *

Buitenhof in which Dutch writer

Cees Nootenboom was interviewed. Cees Nootenboom lives on the Spanish island

Menorca and who has a lot of experience with

Barcelona and

Catalonia and

Spain. Nootenboom who is very sympathetic to the

Catalonians talked about the reality on the ground in

Barcelona and

Catalonia. He went back to history, to

Francoist Spain (1939–1975) in which

the Catalan languaqe and

culture were supressed and prohibited. Nootenboom was very nuanced, neutral and objective and showed both the

Catalonian and

Spanish perspective, but also the perspective of expats and foreign migrants in

Barcelona and

Catalonia. It remained rather peaceful until today, despite the harsh Spanish national police action against the referendum about Independence.

Nootenboom stated that it is very important that Catalonia shouldn't become another Basque Country or Northern Ireland. Fact is that next to the Pro-Independence majority of

Catalonians who voted '

Yes' in the referendum you have a large minority of

Pro-Spanish Catalonians and

Spanish people who live in

Catalonia. Nootenboom pointed at the fact that

the Catalonian police might not remain neutral and peaceful if it would be disbanded or replaced by

Spanish police forces coming from Madrid, Aragon, Castile and León, Castile-La Mancha, Valencian community, Extremadura, Galicia, Asturias, Cantabria, la Rioja, Navarre and Andalusia, other regions of

Spain. The Spanish government in my opinion won't use the Basque police,

Ertzaintza, due to communication problems and the fact that the

Ertzaintza is linked to the Nationalist Basque authorities. Catalonian nationalism is fierce and fanatic, and has a long history. The

Catalonians will not allow their Independence vote being taken from them.

Cees Nootenboom pointed at the political, financial-economical, cultural and human implications of

a Catalonian independence. The

Spanish and

Catalonian economies are very intertwined. Many

Catalonians live and work in other parts of

Spain and many

Spanish people live and work in

Barcelona and other towns and cities of

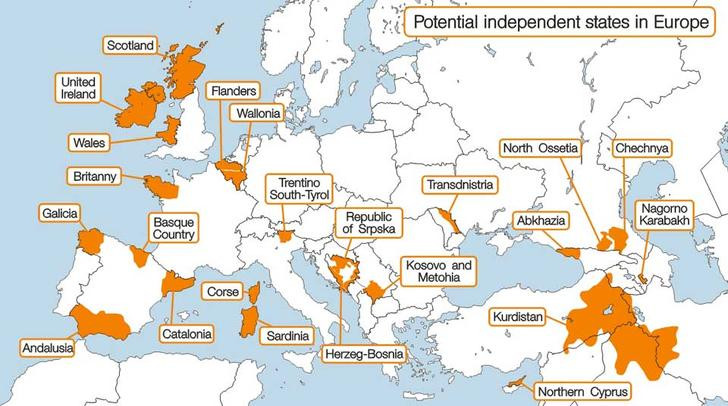

Catalonia. The European Union is against independence, because it fears of segregational developments all over the EU. Whether there will be a conflict between

Madrid and

Barcelona, between the

Catalonians and

the Spanish the near future will show us. I hope that with more autonomy, but it also could develop in the direction of the Dutch

Status aparte for the island Aruba from 1986 until 2010.

Status aparte is a Latin phrase referring to the "

special status" of a dependent territory or a region or a country, being an area that does not have political independence or sovereignty, but is rather considered as a special administrative region. The status of dependency within the Kingdom of the Netherlands is an example of such status. Today Spain with it's history of

Basque and

Catalan separatism and militant

Basque and

Catalan nationalism as the rootcause of that

separatism is very distrustful of

the Catalonians. The pressure on

the Catalonian government,

the Catalonian parliament,

Catalan Pro-Independence Nationalist politicians and

the Catalonians who voted '

Yes' in

the Referendum is huge. They fear a Spanish take over, Spanish occupation (by the Spanish police, the Spanish army and Spanish administrators who will replace Catalonian administrators), and they fear

an end of Catalonian autonomy.

First, what is

the Autonomous Community of Catalonia?

The Autonomous Community of Catalonia occupies a triangular area in the northeastern corner of

Spain. It is bordered by

France and

Andorra to the north, the

Mediterranean Sea to the east, the autonomous community of

Valencia to the south, and the autonomous community of

Aragon to the west.

The Pyrenees separate

Catalonia from

France, and to the west

the pre-Pyrenees and

the Ebro River basin mark the border with

Aragon.

Catalonia

Catalonia was formerly a principality of the crown of Aragon, and it has played an important role in the history of the Iberian Peninsula. From the 17th century it was the centre of a separatist movement that sometimes dominated Spanish affairs.

Catalan separatism reemerged in the 19th century in the support given to

Carlism. The resurgence really began in the 1850s, however, when serious efforts were made to revive

Catalan as a living language with its own press and theatre—a movement known as the

Renaixença (“

Rebirth”).

Catalan nationalism became a serious force after 1876, when the defeat of the

Carlists led the church to transfer its support to

the movement for autonomy.

Catalan nationalism had two major strands: a conservative, Roman Catholic one and a more liberal, secular one. The former was initially predominant, particularly in the first decades of the 20th century. By

1913 Catalonia had won

a slight degree of autonomy, but the legislation conferring it was repealed in

1925 by

Miguel Primo de Rivera, who attacked all manifestations of

Catalan nationalism.

Miguel Primo de Rivera (1870 – 1930) was a dictator, aristocrat, and military officer who served as Prime Minister of Spain from 1923 to 1930 during Spain's Restoration era. He deeply believed that it was the politicians who had ruined Spain and that governing without them he could restore the nation. His slogan was "Country, Religion, Monarchy."

Miguel Primo de Rivera (1870 – 1930) was a dictator, aristocrat, and military officer who served as Prime Minister of Spain from 1923 to 1930 during Spain's Restoration era. He deeply believed that it was the politicians who had ruined Spain and that governing without them he could restore the nation. His slogan was "Country, Religion, Monarchy." In the early 1930s, as most of the western world, Spain fell into economic and political chaos. Alfonso XIII appointed General Dámaso Berenguer, one of Primo de Rivera's opponents, to govern. But the monarch had discredited himself by siding with the dictatorship.

Social revolution fermented in Catalonia. In April 1931, General José Sanjurjo informed the King that he could not count on the loyalty of the armed forces. Alfonso XIII suspended the monarchy on 14 April 1931, leaving the royal family in Madrid. The act ushered in the Second Republic. Two years later Primo de Rivera's eldest son, José Antonio, founded the Falange, a Spanish fascist party.

The first pro-independence political party in

Catalonia was

Estat Català (

Catalan State), founded in 1922 by Francesc Macià. Estat Català went into exile in

France during the dictatorship of

Primo de Rivera (1923–1930), launching an unsuccessful uprising from Prats de Molló in 1926. In March 1931, following the overthrow of Primo de Rivera,

Estat Català joined with the

Partit Republicà Català (

Catalan Republican Party) and the political group

L'Opinió (

Opinion) to form a left-wing coalition party in Catalonia

Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya (

Republican Left of Catalonia;

ERC), with

Macià as its first leader. The following month, the

ERC achieved a spectacular victory in the municipal elections that preceded the 14 April proclamation of

the Second Spanish Republic.

Macià proclaimed

a Catalan Republic on 14 April, but after negotiations with the provisional government he was obliged to

settle for autonomy, under a revived

Generalitat of Catalonia.

Catalonia was granted a statute of

autonomy in

1932, which lasted until

the Spanish Civil War. In

1938,

General Franco abolished both the Statute of Autonomy and the Generalitat.

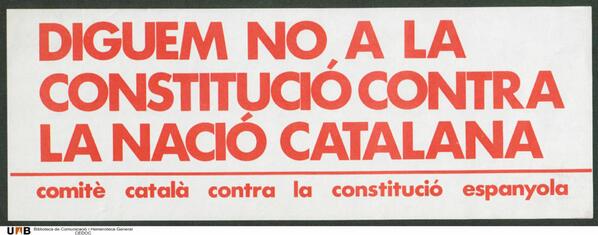

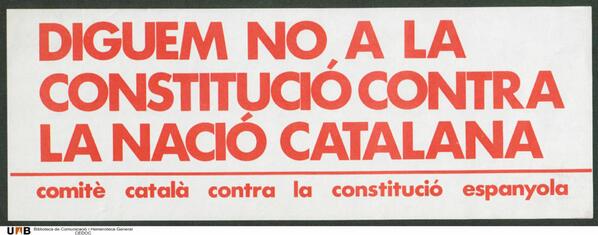

Poster of the first pro-independence political party in Catalonia was Estat Català (Catalan State)Catalonia

Poster of the first pro-independence political party in Catalonia was Estat Català (Catalan State)Catalonia played a prominent role in t

he history of Republican Spain and in

the Civil War (1936–39).

The Nationalists’ victory in

1939 meant

the loss of autonomy, however, and

Gen. Francisco Franco’s government adopted a repressive policy toward

Catalan nationalism.

Celebration of the victory of Esquerra Republicana in the municipal elections of 1931

Celebration of the victory of Esquerra Republicana in the municipal elections of 1931A section of

Estat Català which had broken away from the

ERC in

1936 joined with other groups to found the

Front Nacional de Catalunya (

National Front of Catalonia;

FNC) in

Paris in

1940. The

FNC declared its aim to be "

an energetic protest against Franco and an affirmation of Catalan nationalism". Its impact, however, was on

Catalan exiles in

France rather than in

Catalonia itself. The

FNC in turn gave rise to the

Partit Socialista d'Alliberament Nacional (

Socialist Party of National Liberation;

PSAN), which combined a pro-independence agenda with a left-wing stance. A split in the

PSAN led to the formation of the

Partit Socialista d'Alliberament Nacional - Provisional (

Socialist Party of National Liberation - Provisional; PSAN-P) in

1974.

A Pro-Catalan Independence demonstration of the leftwing nationalist Socialist Party of National Liberation - Provisional (PSAN-P) in 1977

A Pro-Catalan Independence demonstration of the leftwing nationalist Socialist Party of National Liberation - Provisional (PSAN-P) in 1977Following

Franco's death in

1975,

Spain moved to restore democracy. A new constitution was adopted in 1978, which asserted the "indivisible unity of the Spanish Nation", but acknowledged "the right to autonomy of the nationalities and regions which form it". Independence parties objected to it on the basis that it was incompatible with Catalan self-determination, and formed the Comité Català Contra la Constitució Espanyola (Catalan Committee Against the Constitution) to oppose it. The constitution was approved in a referendum by 88% of voters in Spain overall, and just over 90% in Catalonia. It was followed by the Statute of Autonomy of Catalonia of 1979, which was approved in a referendum, with 88% of voters supporting it. This led to the marginalisation or disappearance of pro-independence political groups, and for a time the gap was filled by militant groups such as Terra Lliure.

Demonstration in 1978 of the Catalan Committee Against the Constitution

Demonstration in 1978 of the Catalan Committee Against the Constitution

The establishment of

democratic rule in Spain after

Franco’s death did not lessen

Catalonia’s desire for autonomy, and in

September 1977 limited autonomy was granted to the region. The pro-autonomy Convergence and Union party was founded the following year, and it served as the dominant political force in

Catalonia over subsequent decades. Full autonomy was granted in 1979 with the establishment of the autonomous community of Catalonia. In 2006

Catalonia was granted “

nation”

status and given the same level of taxation responsibility as

the Spanish central government. Spain’s Constitutional Court struck down portions of this

autonomy statute in 2010, ruling that

Catalans constituted a “

nationality” but that

Catalonia was not, itself, a “

nation.”

Many

Catalans, frustrated at the management of the Spanish economy throughout the euro-zone debt crisis, continued to push for increased fiscal independence from the central government. In 2013

the Catalonian regional parliament passed a measure calling for a referendum on independence from Spain to be held in 2014. Scotland’s referendum on independence from the United Kingdom in September 2014, although ultimately unsuccessful, galvanized the independence movement in

Catalonia. Convergence and Union leader

Artur Mas called for the long-promised, albeit nonbinding, independence referendum to be held on

November 9, 2014. The move was immediately challenged by Spanish Prime Minister

Mariano Rajoy, and the independence campaign was suspended while

the Constitutional Court considered the legality of the vote. Ultimately,

Mas proceeded with the referendum but framed it as an informal poll of Catalan opinion. With more than one-third of registered voters participating in the balloting, over 80 percent expressed a desire for independence.

With

Madrid continuing to oppose his efforts,

Mas called for snap regional parliamentary elections to be held in

September 2015. Framing the contest as a de facto plebiscite on independence,

Mas led the

Junts pel Sí (“

Together for Yes”) alliance that won 62 of the 135 seats in

the Catalan parliament. The antiausterity Popular Unity Candidacy, which won 10 seats, entered into a coalition with

Junts pel Sí to give pro-independence parties a narrow parliamentary majority. Those who favoured independence interpreted the result as a victory, while those who opposed it emphasized the fact that pro-independence parties received just 48 percent of the popular vote. On November 9, 2015,

the Catalan parliament narrowly approved a measure to implement a “

peaceful disconnection from the Spanish state.”

Rajoy immediately reiterated the central government’s position that any such move would be illegal and opposed by

Madrid.

The Popular Unity Candidacy had opposed the retention of

Mas as

Catalan president, and the survival of the coalition hinged on an agreement between the pro-independence parties regarding a compromise candidate. On January 9, 2016, just hours before a deadline that would have triggered a fresh round of elections, the two groups settled on Carles Puigdemont, the mayor of Girona. Mas stepped aside, although he remained a member of the Catalan parliament, and Puigdemont vowed to continue the efforts to establish an independent Catalan state.

In March 2017 a Spanish court found Mas guilty of contempt for calling the 2014 referendum, and he was barred from holding public office for two years. Undeterred, a defiant Puigdemont announced in June 2017 that Catalonia would hold a binding referendum on independence on October 1, 2017. As the date of the referendum approached, tensions mounted between

Barcelona and

Madrid, and Spanish authorities took increasingly dramatic steps to avert the vote. In late September, Spanish police seized nearly 10 million ballot forms from a warehouse outside

Barcelona, and more than a dozen pro-independence

Catalan officials were arrested. Tens of thousands of people took to the streets to protest, and the Spanish interior ministry responded by moving to assert central control over

the regional Catalan police force. On the eve of the vote, opinion polls found that

Catalans were roughly evenly split on the issue of independence, but an overwhelming majority favoured putting the issue to a fair and legal vote.

Carles Puigdemont i Casamajó, president of the government of Catelonia

Carles Puigdemont i Casamajó, president of the government of Cateloniahe day of the vote was marred by widespread violence as riot police fired rubber bullets into crowds and used fists and batons to physically prevent people from entering polling places. More than 900 prospective voters and dozens of police were injured, and members of the Spanish national police and the Civil Guard seized ballot boxes from polling stations.

Catalan officials stated that turnout was around 42 percent, with 90 percent of voters voicing their support for independence; the chaotic nature of the vote and the confiscation of ballots by Spanish authorities meant that such figures had to be regarded as approximations at best.

Puigdemont addressed both the violence and the result by saying, “On this day of hope and suffering, Catalonia’s citizens have earned the right to have an independent state in the form of a republic.” Rajoy countered by stating that the referendum was a “mockery” of democracy, and Spanish officials blamed police violence on the “irresponsibility of the Catalan government.” International human rights organizations condemned the violence against voters, but the response from EU leaders was largely muted, with most characterizing it as an internal matter for the Spanish government.

The Spanish national police acted violent against the Catalan voters in the referendum, while the Catalan police refrained from violence, but avoided a clash with the Spanish police

The Spanish national police acted violent against the Catalan voters in the referendum, while the Catalan police refrained from violence, but avoided a clash with the Spanish policeOn October 3 a general strike was called to protest Madrid’s heavy-handed response to the referendum, and an estimated 700,000 people took to the streets of

Barcelona. King Felipe VI held a televised public address to urge unity, and he accused

Catalonia’s leaders of recklessness that jeopardized the economic and social stability of all of

Spain. Indeed, in light of the unrest in

Catalonia, analysts scaled back growth projections for the Spanish economy, and observers characterized the situation as Spain’s gravest domestic crisis since a coup attempt in 1981 that had threatened to derail the country’s young democracy. Perhaps emboldened by the events in

Catalonia, on October 22 voters in the northern Italian regions of Veneto and Lombardy overwhelmingly backed referenda that called for greater local autonomy. As

Puigdemont hinted that he would make a formal declaration of independence,

Rajoy threatened to suspend

Catalonia’s autonomy and impose direct rule on the region. On October 27

the Catalan parliament voted to declare independence from Spain. Stating that he had been left with “

no alternative,”

Rajoy responded by asking members of the Spanish Senate to approve the invocation of Article 155 of the Spanish constitution, empowering the central government to take control of

Catalonia’s police, finances, and publicly owned media. The Senate voted 214 to 47 to grant

Rajoy the extraordinary powers over

Catalonia, where lawmakers who had voted for independence faced the possibility of criminal charges of sedition.

Mariano Rajoy Brey, prime minister of Spain

Mariano Rajoy Brey, prime minister of Spain Mariano Rajoy and Carles Puigdemont in 'better times'.

Mariano Rajoy and Carles Puigdemont in 'better times'.

*

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Buitenhof_(TV_series)P.S.- I consider Buitenhof to be the best Dutch tv program on politics, international news, foreign affairs and quality news in general. I watch it every sunday.

Sources: Dutch national television, Britannica and Wikipedia