|

|

Post by pjotr on Dec 10, 2017 22:20:04 GMT 1

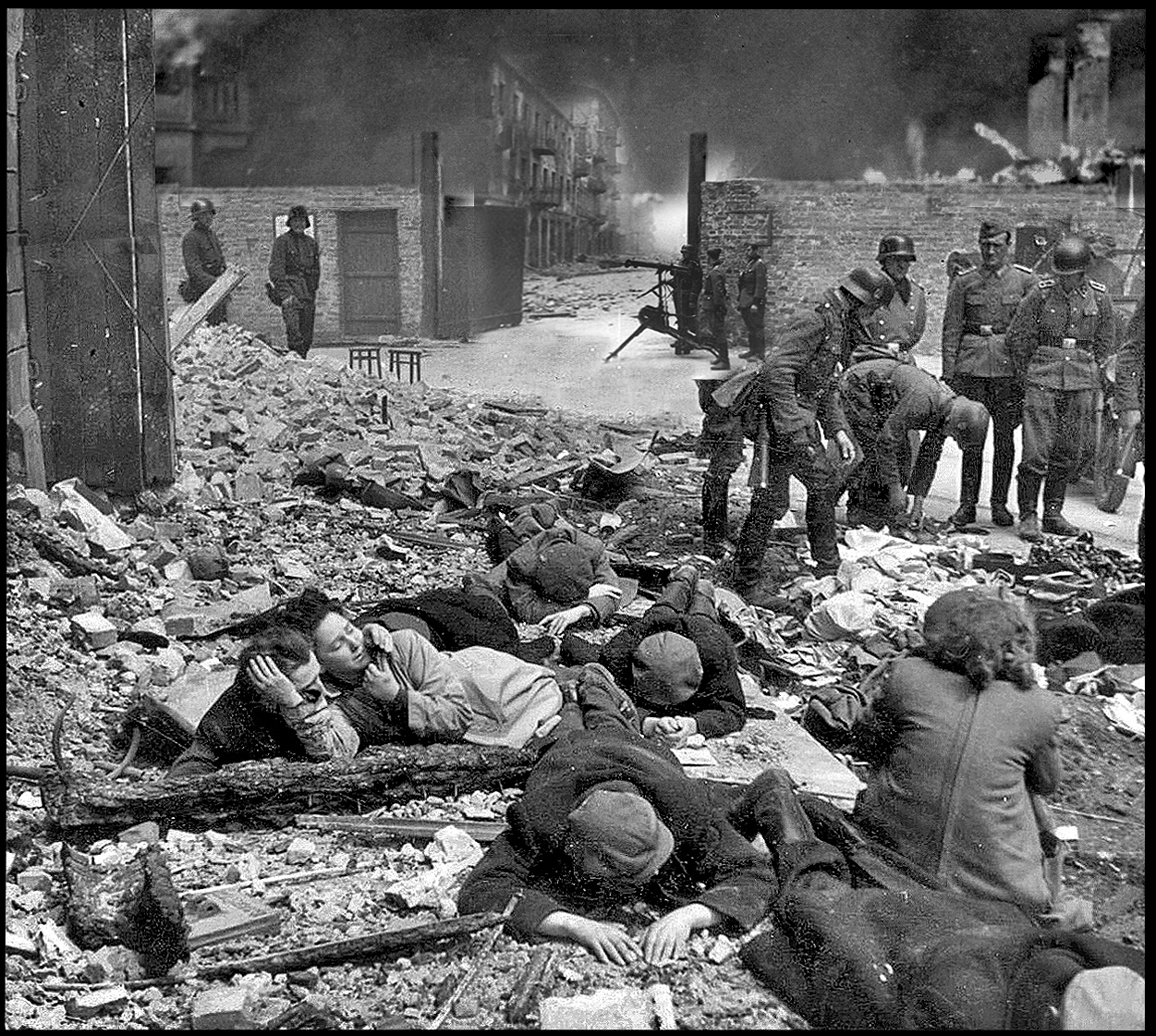

The anthem of the Yiddish Bund, performed by the Workmen's Circle chorus, as a tribute to its last and most valiant partisan. Marek Edelman (1919 - 2009) was the youngest leader of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising and one of its few surviving leaders. He remained in Poland for the rest of his long life and was able to play a significant role in the Solidarnosc movement to finally bring liberty to his long-suffering land. In his last years he spoke out in solidarity with the Palestinians, seeing the parallels between the Warsaw Ghetto and the Gaza Strip all too clearly. May God rest his soul.

The General Jewish Labour Bund in Poland, Algemeyner yidisher arbeter bund, Ogólno-Żydowski Związek Robotniczy was a Polish Jewish socialist party, it was anti-zionist, anti-communist and ant-fascist.

Youth movement Bund

Summer camp Bund and anti-semtic attack

|

|

|

|

Post by pjotr on Dec 10, 2017 22:20:20 GMT 1

|

|

|

|

Post by pjotr on Dec 10, 2017 23:22:08 GMT 1

A meeting of the Bundist Youth Organization, Warsaw, Poland, 1932. A meeting of the Bundist Youth Organization, Warsaw, Poland, 1932.  Members of the Jewish Labor Bund marching at a May Day demonstration in Warsaw. 1930s. Members of the Jewish Labor Bund marching at a May Day demonstration in Warsaw. 1930s. A Bund demonstration in Poland after the war A Bund demonstration in Poland after the war |

|

|

|

Post by pjotr on Dec 10, 2017 23:37:19 GMT 1

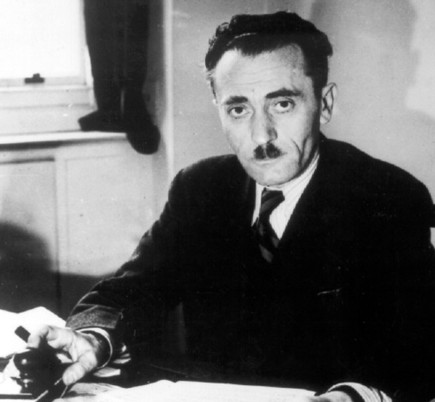

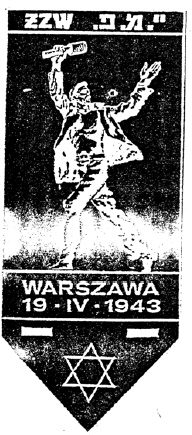

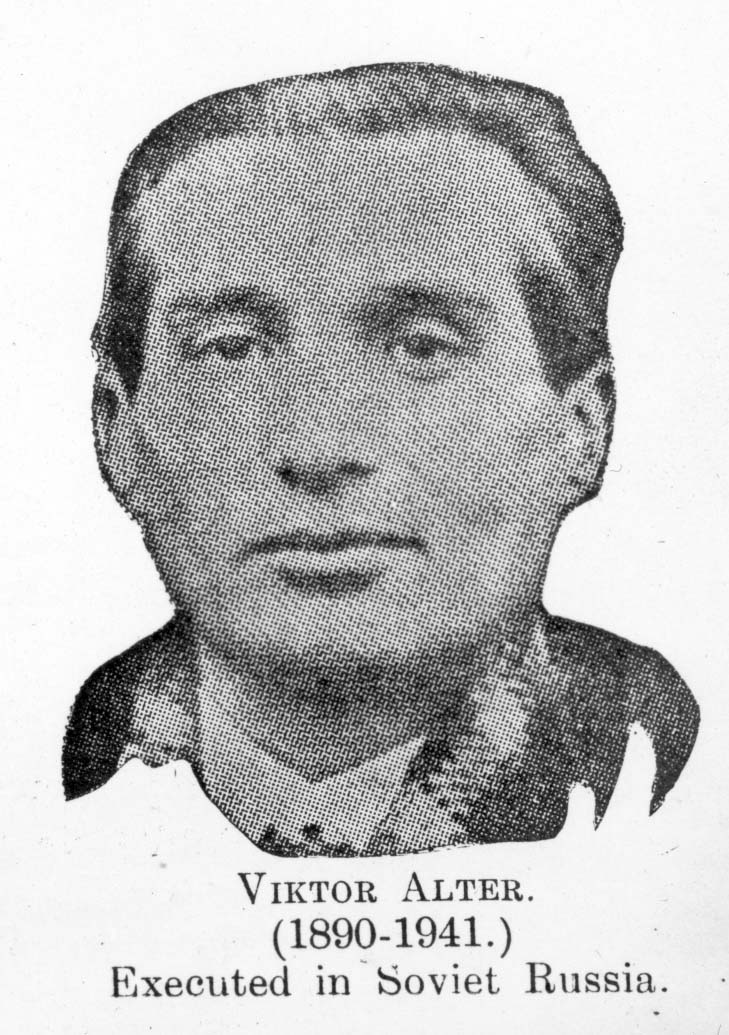

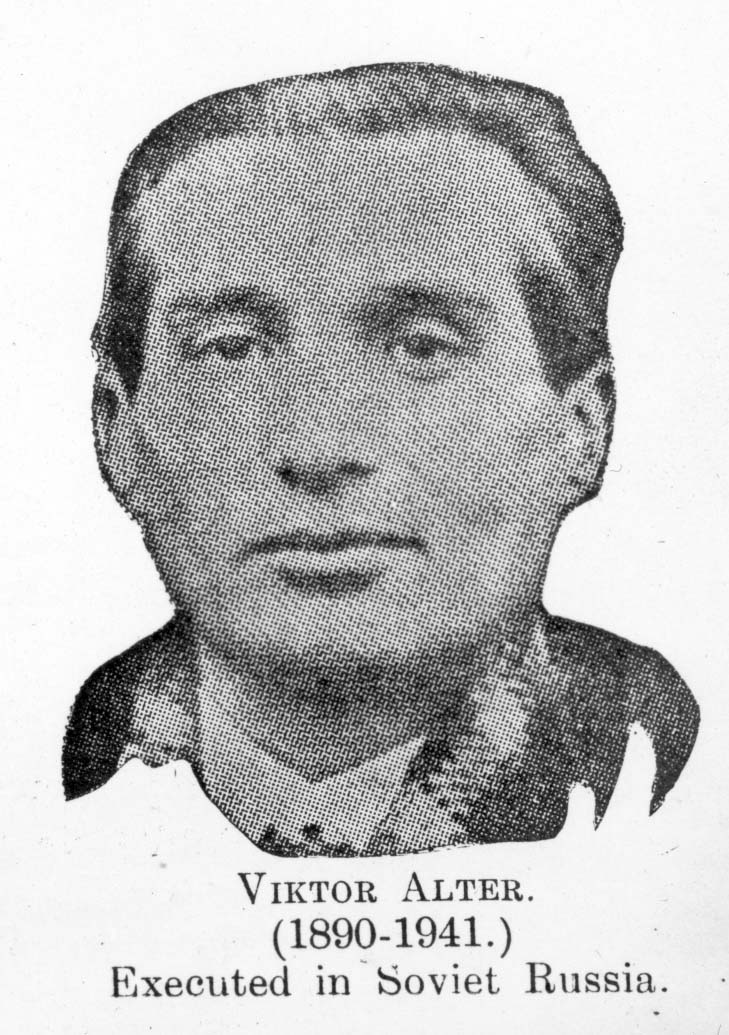

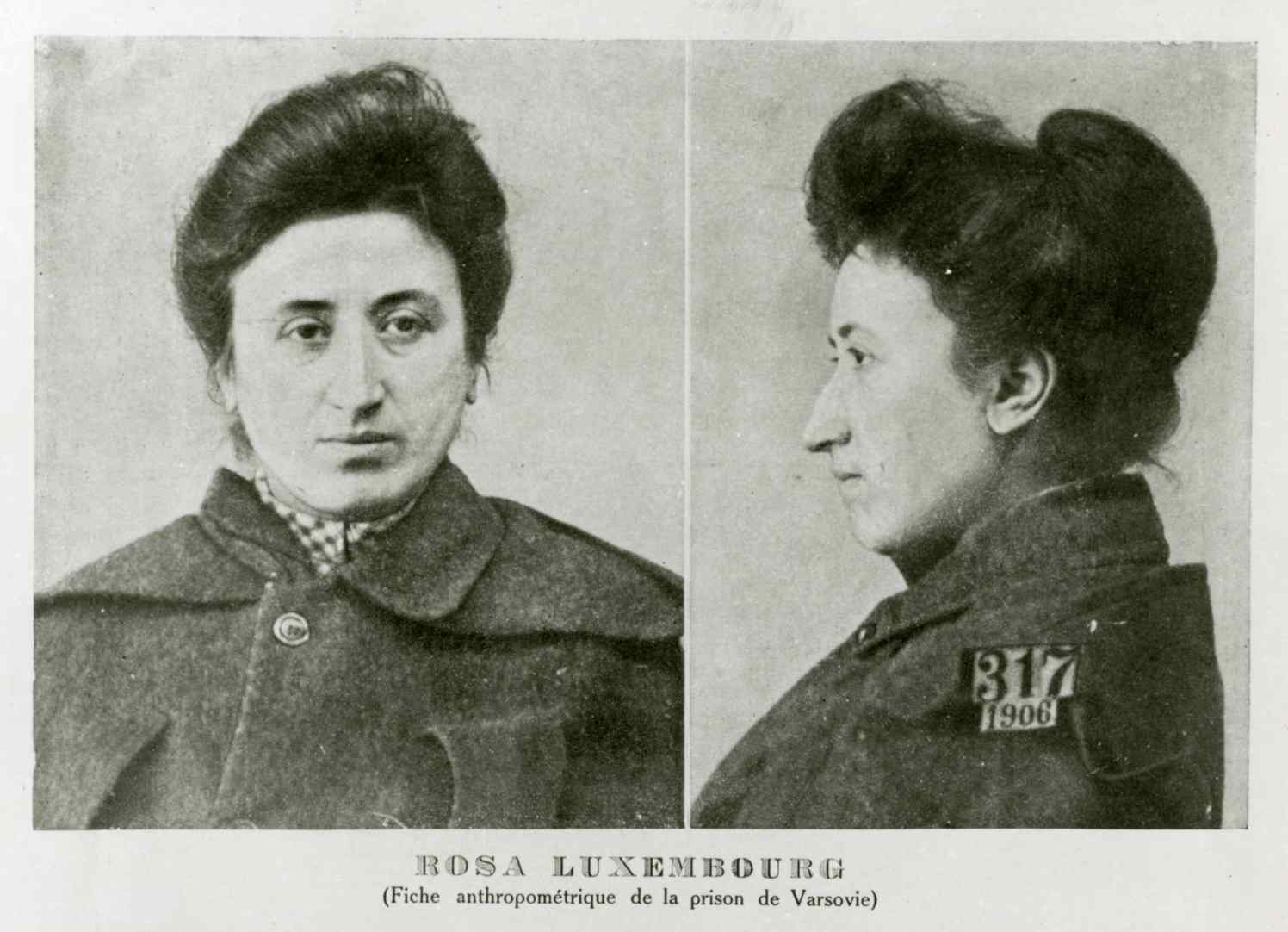

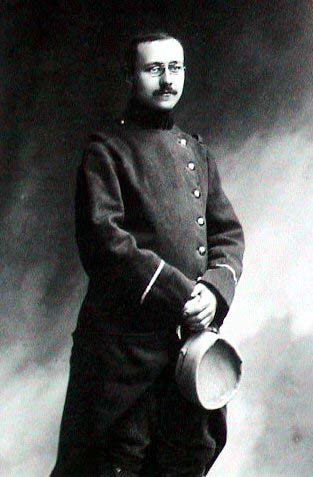

A camp for youngsters in the youth movement of the Bund, held near Warsaw General Jewish Labour Bund in Poland A camp for youngsters in the youth movement of the Bund, held near Warsaw General Jewish Labour Bund in PolandThe General Jewish Labour Bund in Poland (Yiddish: אַלגעמײַנער ײדישער אַרבעטער בּונד אין פוילין tr: Algemeyner yidisher arbeter bund in poyln, Polish: Ogólny Żydowski Związek Robotniczy) was a Jewish socialist party in Poland which promoted the political, cultural and social autonomy of Jewish workers, sought to combat antisemitism and was generally opposed to Zionism. Creation of the Polish BundThe Polish Bund emerged out of the General Jewish Labour Bund in Lithuania, Poland and Russia of the erstwhile Russian empire. The Bund had party structures established amongst the Jewish communities in the Polish areas of the Russian empire. When Poland fell under German occupation in 1914, contact between the Bundists in Poland and the party centre in St. Petersburg became difficult. In November 1914 the Bund Central Committee appointed a separate Committee of Bund Organizations in Poland to run the party in Poland. Theoretically the Bundists in Poland and Russia were members of the same party, but in practice the Polish Bundists operated as a party of their own. In December 1917 the split was formalized, as the Polish Bundists held a clandestine meeting in Lublin and reconstituted themselves as a separate political party. Electoral participationContrarily to the other Jewish parties, the Bund advocated an electoral cooperation with other Socialists, and not just between either Jewish parties or with other minority parties (in the electoral alliance " Bloc of National Minorities"). Thence, Agudat Israel (For religious Orthodox jews, a party loyal to the Polish government), Folkspartei (a liberal bourgeois party of the Polish jewish middle class) and the various Zionist parties were represented in the Sejm, but the Bund never was, mostly because its potential partner, the Polish Socialist Party ( PPS), was reluctant to appear as a pro-Jewish party. The party obtained 81,884 votes (0.9%) at the 1922 Sejm election, approximately 100,000 (0.7%) in the 1928 Sejm election and 66,699 at the largely rigged 1930 Sejm election.  “Zukunft” group - the youth arm of the “Bund” – a Jewish Socialist party which had broad support in PolandIn the autumn of 1933 the party issued a call initiated to the Polish public to boycott of goods from Germany, in protest of the Hitler regime “Zukunft” group - the youth arm of the “Bund” – a Jewish Socialist party which had broad support in PolandIn the autumn of 1933 the party issued a call initiated to the Polish public to boycott of goods from Germany, in protest of the Hitler regime. In December 1938 and January 1939, at the last Polish municipal elections before the start of the Second World War, the Bund received the largest segment of the Jewish vote. In 89 towns, one-third elected Bund majorities. In Warsaw, the Bund won 61.7% of the votes cast for Jewish parties, taking 17 of the 20 municipal council seats won by Jewish parties. In Łódź the Bund won 57.4% ( 11 of 17 seats won by Jewish parties). For the first time, the Bund and the PPS had agreed to call their electors to vote for each other where only one of them presented a list. This however did not go so far as common electoral lists. This alliance made it possible for a Left electoral victory in most great cities: Warsaw, Łódź, Lwow, Piotrkow, Kraków, Białystok, Grodno, Vilnius. After its municipal electoral successes in December 1938 and January 1939, the Bund hoped for a breakthrough at the parliamentary elections due in September 1939, but these were de facto cancelled by the German-Soviet invasion. OrganizationThe party organization was based on local and regional groups, which formed the lowest level of party cells. Each group had its local party committee. The highest authority of the Bund resided with the Party Congress, which elected the Central Committee and the Party Council, an advisory group. The Central Committee was composed of delegates designated by the larger local parties. In 1929 the organization of the party was changed. The Party Council was replaced by the Head Council, which was still organized by the Party Congress, but now the members of Council were selected from the members of the Central Committee. The party was a member of the Labour and Socialist International between September 1930 and 1940. Position towards emigration Marek Edelman Marek EdelmanIn Poland, the activists argued that Jews should stay and fight for socialism rather than emigrate. Marek Edelman once said " The Bundists did not wait for the Messiah, nor did they plan to leave for Palestine. They believed that Poland was their country and they fought for a just, socialist Poland, in which each nationality would have its own cultural autonomy, and in which minorities' rights would be guaranteed." When the Revisionist Zionist leader Vladimir Jabotinsky toured Poland urging the " evacuation" of European Jewry, the Bundists accused him of abetting anti-Semitism. Another non-Zionist Yiddishist Jewish party at the time in Lithuania and Poland was the Folkspartei. World War IIOn August 26, 1939, the party signed the joint statement of socialist parties in Poland, calling for the people to fight against Hitlerism (other signatories included the German Socialist Labour Party of Poland). After the 1939 German-Soviet invasion, the Bund continued to operate as an underground anti-Nazi organization in German-occupied Poland. Several Bund leaders and structures stayed in Soviet-occupied Poland and endured the Stalinist repression. Two most eminent Bund leaders, Wiktor Alter and Henryk Erlich were executed in December 1941 in Moscow on Stalin's orders under accusations of being agents of Nazi Germany.  Wiktor Alter Wiktor Alter Henryk Erlich Henryk ErlichIn 1942, the Bundist Marek Edelman became a cofounder of the Jewish Fighting Organization (Polish: Żydowska Organizacja Bojowa, ŻOB; Yiddish: ייִדישע קאַמף אָרגאַניזאַציע) that led the 1943 Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, and was also part of the Polish resistance movement Armia Krajowa ( Home Army), which fought against the Nazis in the 1944 Warsaw Uprising. From March 1942, Samuel Zygelbojm, a member of the Bund Central Committee since 1924, was the Bund's representative on the National Council of the Polish government in exile in London. He committed suicide on May 12, 1943 to protest the indifference of the Allied governments in the face of the Shoah. Zygielbojm's seat in the Polish exile parliament was overtaken by Emanuel Scherer.  Samuel Zygelbojm, the Bund's representative on the National Council of the Polish government in exile in London Samuel Zygelbojm, the Bund's representative on the National Council of the Polish government in exile in LondonHowever, as a Bundist resistant later wrote, the situation differed between the government in exile and the National Polish Council inside Poland, even in July 1944: " The illegal National Council within the country consisted of four parties, the PPS, the Peasant party, the National Democrats, and the Christian Democrats. These groups were represented in the London parliament-in-exile. So was the Bund, represented first by Artur Ziegelboim and then by Emanuel Scherer. But in Poland the National Council would not accept a representative of the Bund." Post-World War IIAfter the end of the Second World War, the Bund reorganized itself in Poland. Whilst Zionists organized mass emigration to Palestine after the war, the Bund pinned its hopes to a democratic development in Poland. At the time the Bund had between 2,500-3,000 members. Around 500 lived in Łódź. Michal Shuldenfrei was the president of the party, Dr. Shloyme Herschenhorn the vice president. Salo Fiszgrund was the general secretary, assisted by Jozef Jashunski. The party had functioning branches in Warsaw, Łódź and Wrocław. The party ran three publications, Folkstsaytung, Yungt veker and Głos bundu (in Polish). The Bund began setting up various production cooperatives. Together with Jewish communists, the Bund was active in promoting Polish Jews to settle in areas in Silesia that were previously German territories. Antisemitic activities continued in Poland after the war, and in Łódź (the main centre of Jewish population in post-war Poland) the Bund retained a militia structure with a secret armory. The Bund took part in the Polish elections of January 1947 on a common ticket with the Polish Socialist Party ( PPS) and gained its first and only Sejm seat in its history, occupied by Michal Shuldenfrei (already a member of the State National Council since 1944), plus several seats in municipal councils. In 1948 around 400 Bund members illegally left Poland. The Bund was dissolved, along with all other non-communist parties, in 1948 following the consolidation of single-party rule by the Polish United Workers' Party. Schuldenfrei was then ousted from the Communist-led Parliament. In 1976, Marek Edelman, a former Bundist activist and leader during the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, became part of the Workers' Defense Committee ( Komitet Obrony Robotników, KOR) and later part of the Solidarity trade union movement.[28] During the period of martial law in 1981, he was interned. He took part in the Round Table Talks and served as a member of parliament from 1989 until 1993. translate.google.nl/translate?hl=nl&langpair=en|nl&u=http://www.youtube.com/How the Bolsjewists killed Edelman's mother |

|

|

|

Post by pjotr on Dec 11, 2017 0:12:46 GMT 1

|

|

|

|

Post by pjotr on Dec 11, 2017 0:14:38 GMT 1

|

|

|

|

Post by pjotr on Dec 11, 2017 0:48:02 GMT 1

During Marek Edelmans funeral with a Polish military honour guard, the Bund flag was covering the coffin.

|

|

|

|

Post by pjotr on Dec 11, 2017 1:07:36 GMT 1

At a Bund meeting somewhere in Poland during the thirties At a Bund meeting somewhere in Poland during the thirties A Bund demonstration somewhere in Warsaw with Yiddish language authors and other Polish jewish intellectualsSzmul Zygielbojm A Bund demonstration somewhere in Warsaw with Yiddish language authors and other Polish jewish intellectualsSzmul Zygielbojm  Szmul Zygielbojm Szmul Zygielbojm (Polish: [ˈʂmul zɨˈɡʲɛlbɔjm]; Yiddish: שמואל זיגלבוים; February 21, 1895 – May 11, 1943) was a Jewish-Polish socialist politician, leader of the Bund, and a member of the National Council of the Polish government in exile. He committed suicide to protest the indifference of the Allied governments in the face of the Holocaust. In his 20s, Zygielbojm became involved in the Jewish labor movement, and in 1917 he represented Chełm at the first Bundist convention in Poland. Zygielbojm so impressed the Bund leadership at the convention that he was invited to Warsaw in 1920 to serve as secretary of the Trade Union of Jewish Metal Workers and a member of the Warsaw Committee of the Bund. In 1924 he was elected to the Bund's Central Committee, a position he held until his death.  Szmul Zygielbojm Szmul ZygielbojmBy 1930, Zygielbojm was editing the Jewish labor unions' journal, Arbeiter Fragen (" Worker’s Issues"). In 1936, the Central Committee sent him to Łódź to lead the Jewish workers' movement, and in 1938 he was elected to the Łódź city council.  Szmul Zygielbojm is at far the lower right in this photo of the Bund's Central Committee at a 1929 conference. Szmul Zygielbojm is at far the lower right in this photo of the Bund's Central Committee at a 1929 conference.After Germany invaded Poland in September 1939, Zygielbojm returned to Warsaw, where he participated in the defense committee during the siege and defense of the city. When the Nazis occupied Warsaw, they demanded 12 hostages from the population to prevent further resistance. Stefan Starzyński, the city's president, proposed that the Jewish labor movement provide a hostage, Ester Iwińska. Zygielbojm volunteered in her place. On his release, Zygielbojm was made a member of the Jewish Council, or Judenrat, that the Nazis had created. The Nazis ordered the Judenrat to begin the creation of a ghetto within Warsaw. Because of Zygielbojm's public opposition to the order, his fellow Bundists feared for his safety and arranged for him to leave. In December 1939, Zygielbojm reached Belgium. Early in 1940, he spoke before a meeting of the Labour and Socialist International in Brussels and described the early stages of the Nazi persecution of Polish Jewry. When the Nazis invaded Belgium in May 1940, Zygielbojm went to France and then the US, where he spent a year and a half trying to convince Americans of the dire situation facing Jews in Nazi-occupied Poland. In March 1942, he arrived in London to join the National Council of the Polish government in exile, where he was one of two Jewish members (the other was the Zionist Ignacy Schwarzbart). In London, Zygielbojm continued to speak publicly about the fate of Polish Jews, including a meeting of the British Labour Party and a speech broadcast on BBC Radio on June 2, 1942. His booklet, written in English before his suicide in 1942 and titled " Stop Them Now. German Mass Murder of Jews in Poland", with a foreword by Lord (Josiah) Wedgwood, was his final attempt to focus world attention on what was happening to Jews in Europe. I must mention here that the Polish population gives all possible help and sympathy to the Jews. The solidarity of the population in Poland has two aspects: first it is expressed in the common suffering and secondly in the continued joint struggle against the inhuman occupying Power. The fight with the oppressors goes on steadily, stubbornly, secretly, even in the ghetto, under conditions so terrible and inhuman that they are hard to describe or imagine.... The Polish and Jewish population keep in constant touch, exchanging newspapers, views and instructions. The walls of the ghetto have not really separated the Jewish population from the Poles. The Polish and the Jewish masses continue to fight together for common aims, just as they have fought for so many years in the past.But his final letter was different and somber: The responsibility for the crime of the murder of the whole Jewish nationality in Poland rests first of all on those who are carrying it out, but indirectly it falls also upon the whole of humanity, on the peoples of the Allied nations and on their governments, who up to this day have not taken any real steps to halt this crime. By looking on passively upon this murder of defenseless millions tortured children, women and men they have become partners to the responsibility.

I am obliged to state that although the Polish Government contributed largely to the arousing of public opinion in the world, it still did not do enough. It did not do anything that was not routine, that might have been appropriate to the dimensions of the tragedy taking place in Poland....

I cannot continue to live and to be silent while the remnants of Polish Jewry, whose representative I am, are being murdered. My comrades in the Warsaw ghetto fell with arms in their hands in the last heroic battle. I was not permitted to fall like them, together with them, but I belong with them, to their mass grave.

By my death, I wish to give expression to my most profound protest against the inaction in which the world watches and permits the destruction of the Jewish people. |

|

|

|

Post by pjotr on Dec 11, 2017 18:31:45 GMT 1

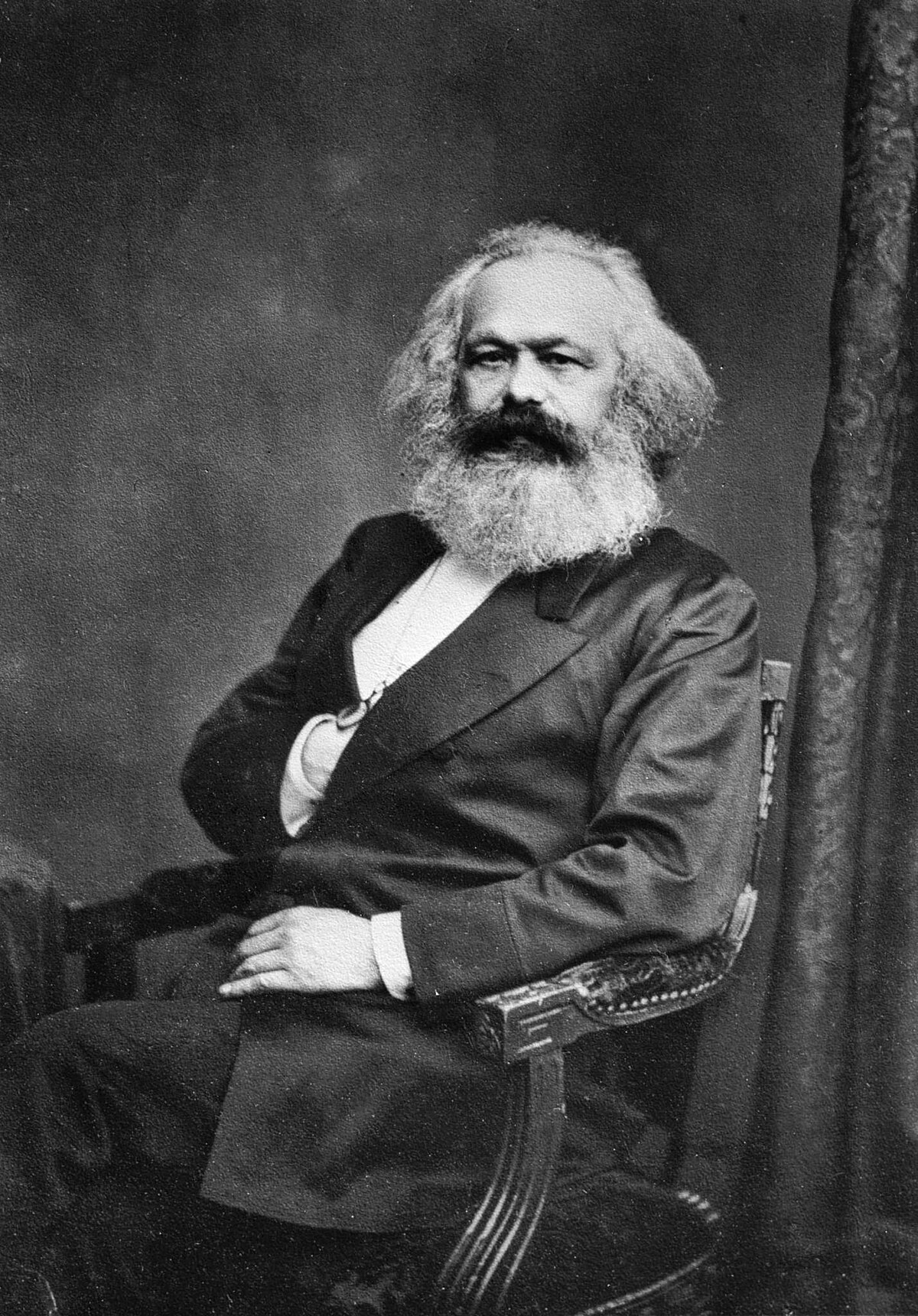

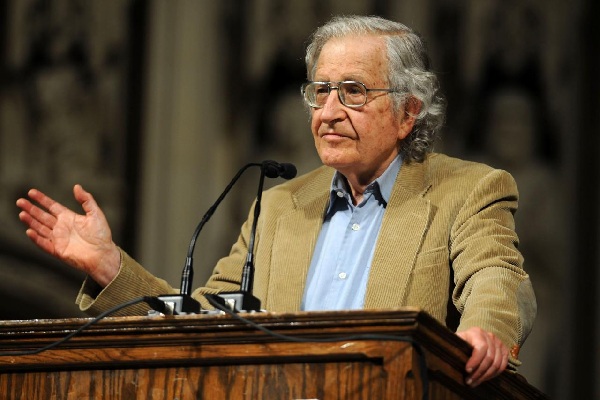

Lessons From the BundBy Samuel Farber A newly translated memoir takes us inside the Jewish Labor Bund's fight for survival and social transformation in 1930s Poland.In the 1930s, Jews constituted 9.5 percent of Poland’s population Lessons From the BundBy Samuel Farber A newly translated memoir takes us inside the Jewish Labor Bund's fight for survival and social transformation in 1930s Poland.In the 1930s, Jews constituted 9.5 percent of Poland’s population. The enormous pressure of European fascism and the dramatic growth of antisemitism politicized the country’s Jewish community, especially its younger members. They were drawn toward Bundism, Zionism, and Communism in massive numbers. By the end of the decade, the Bund had become the hegemonic union and political force among Polish Jews. Founded in 1897 as the General Jewish Labor Bund in Russia and Poland, the Polish Bund became a separate organization during World War I, when opposed occupying armies cut off communication between the Polish and Russian chapters. In the interwar years, the Polish Bund’s success came from its call to maintain cultural autonomy, including preserving Yiddish language and culture, its aggressive defense of the Jewish community, and its labor militancy. Unlike Zionism, the Polish Bund insisted, under its doctrine of “ hereness” ( doikayt in Yiddish), that the right place for Jews was where they already lived. Trying to escape antisemitism by moving to Palestine — which, it reminded its members, was not empty land — and establishing a Jewish state would be unjust and provoke resistance. Instead, Jews had a duty to fight in alliance with the labor movement and with socialist organizations to establish a democratic republic in Poland. Wikipedia quote by Pieter:In Poland, the Bund activists argued that Jews should stay and fight for socialism rather than emigrate. Marek Edelman once said " The Bundists did not wait for the Messiah, nor did they plan to leave for Palestine. They believed that Poland was their country and they fought for a just, socialist Poland, in which each nationality would have its own cultural autonomy, and in which minorities' rights would be guaranteed.". When the Revisionist Zionist leader Vladimir Jabotinsky toured Poland urging the " evacuation" of European Jewry, the Bundists accused him of abetting anti-Semitism. Another non-Zionist Yiddishist Jewish party at the time in Lithuania and Poland was the Folkspartei. End wikipedia quote!The Bund’s demands for cultural autonomy put it on a collision course with the Russian Social Democratic Party ( RSLDP), which it had joined in 1898. When its demands for autonomy were rejected in 1903, the Bund split and reestablished its separate existence. Admittedly, some of the Bund’s demands — such as becoming the exclusive representative of all Jewish workers no matter what language they spoke or where they lived — could not be justified. But Bolsheviks and Mensheviks, influenced by their assimiliationist expectations, refused to treat Jews like other national groups within the empire. By the 1930s, the Bund was successfully recruiting left-wing support not only because of its defense of Jewish culture, but also because of its combative social-democratic line, which appeared as an alternative both to Stalinism and Zionism. Bernard Goldstein richly portrays the organization’s history during those fateful interwar years in his recently translated memoir, Twenty Years with the Jewish Labor Bund. There, he speaks both as a Bund member and as head of its Warsaw militia. Taken with The Stars Bear Witness — his account of life in the Warsaw Ghetto and its 1943 rebellion, led by a coalition of Bundists, Zionists, and Communists organized into the Jewish Fighting Organization ( Żydowska Organizacja Bojowa, ŻOB) — Goldstein covers the Bund’s rise and fall. Only a few of them survived amongst them the later Polish doctor and KOR & Solidarność activist Marek Edelman. Comment Pieter the other group of fighting jews was the more rightwing Jewish Military League (Polish: Żydowski Związek Wojskowy, ŻZW), formed primarily of former Polish Jewish officers of the Polish Army in late 1939. Due to the ŻZW's close ties with the Armia Krajowa ( AK), which was closely linked to the Polish Government in Exile, after the war the Soviet-dependent People's Republic of Poland suppressed publication of books and articles on ŻZW. Its role in the uprising in the ghetto was downplayed, in favour of the more socialist Żydowska Organizacja Bojowa ( Jewish Fighting Organization).  The flag of the Jewish Fighting Organization, ŻOB, in the Warsaw Ghetto uprising in 1943Warsaw jews fought until their death against the Waffen-SS in the Warsaw Ghetto The flag of the Jewish Fighting Organization, ŻOB, in the Warsaw Ghetto uprising in 1943Warsaw jews fought until their death against the Waffen-SS in the Warsaw Ghetto A poster of the Żydowski Związek Wojskowy, the Jewish Military League, in the Warsaw Ghetto of 1943. A poster of the Żydowski Związek Wojskowy, the Jewish Military League, in the Warsaw Ghetto of 1943. The flag of the Jewish Military Union, ŻZW, who fought together with the Jewish Fighting Organization, ŻOB, and units of the Armia Krajowa (Home Army) during the the Warsaw Ghetto uprising in 1943A Well Regulated MilitiaGoldstein The flag of the Jewish Military Union, ŻZW, who fought together with the Jewish Fighting Organization, ŻOB, and units of the Armia Krajowa (Home Army) during the the Warsaw Ghetto uprising in 1943A Well Regulated MilitiaGoldstein’s account explodes the Zionist narrative that contrasts brave Israeli warriors with meek and submissive Eastern European Jews. As Goldstein relates, from 1905 until the early 1920s, the Jewish Bund engaged in self-defense as the need arose. Members would create ad hoc security forces for events and demonstrations or to ward off attacks. But as antisemitism and conflicts with Communists grew, the Bund’s central committee decided to organize a permanent militia, naming Goldstein to head it. The new militia traced its roots to the Zelbst-shuts ( self-defense) units that had participated in the 1905 Russian Revolution. Goldstein describes his newly formed militia’s discipline. Its members could not use firearms unless specifically ordered to do so nor could they act on their own to seek revenge for attacks. According to Goldstein, the party established these rules to prevent the militia from degenerating into outright banditry, as some revolutionary groups in tsarist Russia, like the Socialist Revolutionary Party ( SRP) and the Polish Socialist Party ( PPS), did. Further, the Bund did not grant the militia any special privileges and in fact imposed stricter rules on them than on other party members. Militia members had to pay party dues and, like other Bundists who had to miss work to fulfill a party assignment, were not compensated for lost wages while on duty. The militia had its own sick fund to take care of those who had been wounded on duty. Occasionally, the militia went beyond self-defense and behaved more proactively. Goldstein recounts instances when he tried to stop evictions by negotiating with landlords. When it didn’t work, militiamen appeared in the building’s courtyard, waited for the authorities to move the tenant’s possessions into the street, and then carried them back to the apartment once the bailiff and police had left. They repeated the whole operation until the landlord agreed to work out a compromise. The Bund militia grew at the same pace as the Bund’s political influence. By 1939, as many as twenty thousand people attended Bund rallies with some two thousand militia members guarding them. Goldstein details the militia’s exhaustive defense preparations: for marches, members would station themselves in every tenth rank. Other groups positioned throughout the crowd would watch people on the side streets and look out for police or hostile counterprotesters. The militia also expanded in response to the new waves of antisemitism that swept Poland after the Second Republic’s founding in 1918. For one, the Bund had to deal with Haller’s Army, followers of the nationalist war hero Józef Haller, who used to beat up Jews and cut off the beards of the pious in the streets of Warsaw and in provincial towns. The police also took a hostile stance to the Bund, ransacking and seizing their clubs and offices, as they did in the Warsaw suburb of Praga in 1 920. The Bund also violently clashed with religious Jews when, in 1922, it decided to publish a Saturday edition of their newspaper Folkstsaytung, violating the Sabbath rest. Antisemitism became an even greater threat in the 1930s thanks to Hitler’s rise and Poland’s increasingly dictatorial and nationalist government. Physical attacks on Jews increased, and pogroms reappeared. Polish students, strongly influenced by Polish Nazism (National Democracy, Phalanga, Oboz Narodowo Radykalny-Falanga, ONR-Falanga), established a ghetto for Jews at the university, forcing them to sit on specially assigned benches on the left side of the classrooms. The Polish government sanctioned this practice in 1937, decreeing it the law of the land. In response, all Jewish parties joined the Bund in declaring a general strike. The Bund and the CominternWhile fighting antisemitism, the Bund militia also had to deal with the Communist International. After the 1917 Russian Revolution and especially following the Comintern’s 1919 founding, serious tensions developed between the Communists and the Bund, eventually fracturing the party. The pro-Communist faction, called the Kombund, represented a substantial part of the membership. It demanded that the Bund accept all twenty-one conditions that the Comintern had stipulated for party membership. The three other factions — the left-wing majority, the centrists, and the small right-wing faction that eventually joined the center — refused to accept several of the twenty-one conditions. As a result, the Kombund defected and joined the Communists. The two parties had to compete for Jewish workers’ allegiance and remained in sometimes violent conflict with each other. These occasional clashes did not prevent the Bund’s open opposition to the war craze that swept Poland after World War I, as nationalist forces called for extending the nation from the Baltic to the Black Seas at the expense of revolutionary Russia. In fact, Henryk Erlich, one of the Bund’s main leaders, spoke at the Warsaw city council to demand that the government repudiate plans to capture Ukraine and instead seek an immediate and just peace with Soviet Russia. Amid this turmoil, Goldstein reports that the Bund jointly participated with the Communists and with the Polish Socialist Party ( Polska Partia Socjalistyczna, PPS) in the 1920 Warsaw May Day parade. Whatever friction and violence excited up to this point pales in comparison to what happened after 1928, when Stalin and the Comintern adopted the ultra-left “ Third Period” policies. Inside the Soviet Union, this justified the first Five Year Plan, which mercilessly crushed the peasantry and created the 1932–33 Ukrainian famine ( Holodomor) to advance Stalin’s forced industrialization. Internationally, the period represented an ultra-sectarian line that denounced all other left political groups and attacked social democrats as social fascists. This policy, together with the German Social Democratic Party’s ( SPD) timid and conservative politics, opened the door for Hitler’s rise to power. Since the Bundists were also social democrats — albeit far more combative than the SPD — Third Period Communists unleashed an all-out war against them. This included attempts to split Bund-led unions by calling for wildcat strikes without any justification or worker support, which frequently entailed physically attacking the uncooperative workers. Goldstein describes the tailors’ wildcat strike, which the Communists forced in the summer of 1930 and ended with severely injured workers. Beyond those reckless actions, Goldstein describes assaults on Bund institutions, like the Medem Sanitarium for children. In 1931, 150 Jewish and Polish Communists attacked it, destroying the electrical station and kitchen, breaking all the windows, and engaging in a wild shooting spree. Fortunately, all the children had been evacuated. Communist persecution of the Bund did not stop with Stalin’s adoption of the Popular Front policy in 1935 or his subsequent national-unity policy against Nazism. It continued for years, and took the lives of two Bund leaders: Henryk Erlich and Victor Alter. Alter was executed, and Erlich driven to suicide by the Soviet authorities in 1943.  Henryk Erlich Henryk Erlich  Victor AlterWorking-Class UnityThe Bund’s leaders Victor AlterWorking-Class UnityThe Bund’s leaders realized that its militia alone could not protect its members from Communist excesses or from the far more important problem of Polish antisemitism, which affected the Jewish community at large. That is why they — even if they were not revolutionary Bolsheviks — argued for the unity of the Polish working class while advocating for the Jewish minority’s special cultural and national demands, including that “ each union in any city with a large Jewish component should be required to form a separate Jewish affiliate.” To accomplish this, the Bund had to face the power that nationalism and antisemitism had over non-Jewish workers. Goldstein portrays these tensions by telling a story of bloody worker conflict in the slaughterhouses. Private merchants bought most of the meat, but the municipal and national governments, public hospitals, and the military were clients as well. The Polish workers maintained that, as ethnic Poles, they should get a larger share of the government work, a claim the Jewish workers obviously disputed. At one point the conflict almost turned into a nightmare, as workers lined up on either side ready to use their butcher knives against each other. The dispute was resolved only after Goldstein, acting on behalf of the Jewish union, persuaded the Polish union’s secretary, a member of the PPS — a non-Marxist and nationalist-inclined socialist party — to jointly address the workers and convince them to lay down their weapons and settle the dispute.While one might object to organizing a union along ethnic lines, the practice undoubtedly came in response to the systemic discrimination — from both private and public employers — that Jewish workers faced. Goldstein provides a detailed example of this at the Central Provisions Administration Office, which once employed some two hundred Jewish workers. Soon after the Warsaw City Council took over the office, it began to dismiss its Jewish employees, claiming that the office was gradually being liquidated. With the help of PPS and Communist workplace activists, the Bund mounted a successful campaign against the discriminatory layoffs. Goldstein’s description makes it clear that the Bund conducted much of its work in collaboration with the PPS, despite the latter’s reluctance to identify as a pro-Jewish party. For this and other reasons, relations between the two organizations wavered, but they improved significantly in the 1930s, during Jozef Pilsudski’s increasingly dictatorial regime. Pilsudski, a one-time PPS leader, dealt serious blows to his former party and to the democratic opposition in general. As a result, the Bund and PPS jointly organized the 1931 May Day demonstration. Among other dramatic incidents in which the Bund, unionized Polish workers, and the PPS came together, Goldstein describes their open fights against fascist and antisemitic demonstrations in Warsaw’s Saxon Gardens and their successful effort to stop a pogrom in the city of Brisk. The Bundist Brand of UnionismAs a party in the classic social-democratic mold, the Bund built a dense counter-society within antisemitic and reactionary Poland that could encompass every aspect of Jewish life. The party had sections for youth ( Tsukunft), women ( Yidishe Arbeter Froy), and even children ( SKIF or the Union of Socialist Children). It had a Yiddish-speaking school system, a sports and athletic section, and a sanatorioum for children named after Vladimir Medem, one of its leading founders. As a Marxist party, however, its central priority was organizing the Jewish working class. Goldstein’s book brings to light one important aspect of the Bund-led unions: their odd combination of modern and traditional practices. On the one hand, they experienced the very modern conflict between centralization and autonomy. Goldstein explains that the Warsaw unions demanded control of locals in the Praga suburb, hoping to collect their members’ dues and organize their activities centrally. The Praga unionists objected and demanded more autonomy. The Warsaw unions eventually allowed their suburban affiliates to take dues and address local issues — like negotiations and limited strikes. But Warsaw retained control over industry-wide strikes and general demands, requiring the Praga unions to submit to the central office on those issues. These modern disputes mixed with instances of extremely traditional craft unionism. For example, Goldstein explains that the slaughterhouse union was split into separate locals according to an extremely detailed division of labor. There were separate groups for the drivers who moved the cattle and other animals from the train to the stalls, the skinners, the hide haulers and the meat haulers, the record-keepers, the teamsters who delivered to the butcher shops, the tripe workers, and those who worked only with calves. While this archaic organization did not contribute to union solidarity, other traditional union traits did. For example, the slaughterhouse locals worked on a cooperative basis: everything they earned went into a pool and, at the end of each week, the proceeds were distributed according to rules that stressed need. For example, an unmarried man, regardless of his qualifications, received a smaller share than a married man. The back porters — workers who transported burdens on their backs — improvised their own social security system. A sick porter continued to receive his share of the pool; if he died, the vacant spot went to his son or son-in-law; if there was no son or son-in-law to take his place, the porter’s station paid the widow a weekly pension for one year. In many other craft trades, especially among bakers, fully employed workers gave up their overtime hours to their unemployed comrades. The Bund sanctioned these practices, which were rooted in a precapitalist moral economy, but resisted others that violated that morality. For example, the slaughterhouse owners tolerated the workers’ practice of stealing a little meat for household consumption. When some porters took two bundles of leather from a small merchant in order to sell them, however, the Bund forced them to return the product. Goldstein points out that the public received this very well, helping the Bund’s image. Off the Shop FloorGoldstein also shows that the Bund did not confine its attention to a narrowly defined Jewish working class. Polish Jews experienced deep and extensive poverty; Jewish beggars tried to survive all over Warsaw; and many Polish Jews, particularly women, never learned to read. The Jewish working class in Warsaw lived side by side with a world of marginalized people into which workers and their families could easily fall. The Bund did not ignore that world. Goldstein writes about how, in order to develop contacts among the Jewish transport workers in Praga, he attended a wedding of known thieves. He also describes visiting a synagogue frequented by criminals, pimps, sex workers, and other underworld characters who were allowed to pray there between the Jewish New Year and Day of Atonement. Goldstein’s memoir makes clear that the Bund did not pander to and romanticize this world, nor did it condescend with moralizing self-righteousness. Instead, it always attempted to bring its inhabitants into what, as Goldstein put it, was a world of new ideas and concepts, a new culture, a new way of thinking and talking, and new and broader interests. In short [to become] aware of general social problems and a different way of life, things they were never before concerned with or had even thought about. Yet in offering its model of an alternative society, the Bund ran into some unanticipated obstacles. Goldstein tells the story of a Bund activist who got so involved in his union that he increasingly distanced himself from his illiterate wife, who was left isolated at home tending to their children and household duties. After the wife contacted Goldstein, he approached the husband, who explained that he had nothing to talk to his wife about. Goldstein discovered that the wife had gotten a tutor, learned to read, and wanted to join the Bund, but the husband did not want his wife to become an activist. Goldstein tried to persuade him but concluded that somehow these two things could not coexist in [the husband’s] mind: the Socialist program about equality for women and the fact that his wife leaves the house several times a week to attend meetings of the YAF [the Bund’s women’s organization], and that he must sit at home and watch the children. Goldstein’s own conception of the Bund was somewhat contradictory as well. He affirms, on one hand, that the organization never confined itself to socialist mass struggle: “ We concerned ourselves with the personal problems of the workers’ lives as well.” A few pages later, however, he tells a member’s wife — who complains that her husband does not contribute to household finances — that the Bund “ cannot mix into people’s private affairs,” an answer readers might expect from a modern socialist party organizer. The woman’s reply, however, got straight to the point: “ Comrade Bernard, to whom can I go? Who can help me? . . . Let him at least give the household something to live on.” In the end, Goldstein appealed to the husband’s brothers, who successfully pressured him into discharging his financial responsibilities. The grateful woman became an ardent election campaigner for the Bund. Jewish working-class life had converted Bund organizer Goldstein into a part-time rabbi and social worker. The Rise Before the FallThe Bund’s hegemony took on many forms. In the 1930s, one hundred thousand Jewish workers belonged to unions, meaning that one-quarter of all unionized workers in Poland were led by the Bund, giving them enormous power. For example, it led the 1936 general strike against the Przytyk pogrom ( en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Przytyk_pogrom ). All Jewish workers left work, Jewish stores shut down, and pupils walked out of school. Electorally, the Bund started to make headway in the kehilla — Jewish community council — elections in 1936 and later in the 1938 Warsaw City Council elections. Out of twenty Jewish councilmen, seventeen candidates associated with the Bund were elected. Similar results came in from Łódź, Wilno, Lublin, Białystok, Grodno, Piotrków, Tarnow, and other cities. The Bund also performed well in municipal elections held in January 1939. An agreement with the PPS facilitated these successes. Each party called on their bases to support the other when only one had presented a slate. In light of its excellent results in local elections, the Bund hoped to do very well in the parliamentary elections that were supposed to take place in September 1939. They were, of course, preempted by the German invasion that began on September 1 and by the Soviet invasion just two weeks later. Thus, the Nazi genocide of the Jewish community in Poland, Eastern Europe, and elsewhere began. While in 1933 there had been three million Polish Jews, by 1950 only forty-five thousand remained. The threat of pogroms and the harsh realities of the new Stalinist regime reduced this group even further within a few years. In the immediate postwar period, large numbers of Jewish refugees waited for visas to the United States and other capitalist democracies. By and large, these countries refused to admit them, and many ended up in Palestine, joining the substantial number of German Jews who had already fled there. This played a key role in building the hegemony of Zionism over Jewish communities all over the world. The original settlers only had the support of a minority current of Jewish opinion, competing against both leftist and religious parties. But the horrors of the Holocaust and the plight of Jewish refugees granted a new international legitimacy to the Zionist project. At the same time, as its social base had been virtually exterminated, the Bund ceased to exist as a mass movement. Still, the Left would do well to learn from the Bund, as it combined the defense of an oppressed community with broad worker alliances, mixing anti-discriminatory and pro-worker activism into an effective and popular political force. About the Author Samuel Farber Samuel FarberSamuel Farber was born and raised in Cuba and has written extensively on that country. His newest book, The Politics of Che Guevara: Theory and Practice, is out now from Haymarket Books. Source: Jacobin is a leading voice of the American left, offering socialist perspectives on politics, economics, and culture. The print magazine is released quarterly and reaches over 30,000 subscribers, in addition to a web audience of 1,000,000 a month. |

|

|

|

Post by pjotr on Dec 12, 2017 17:30:49 GMT 1

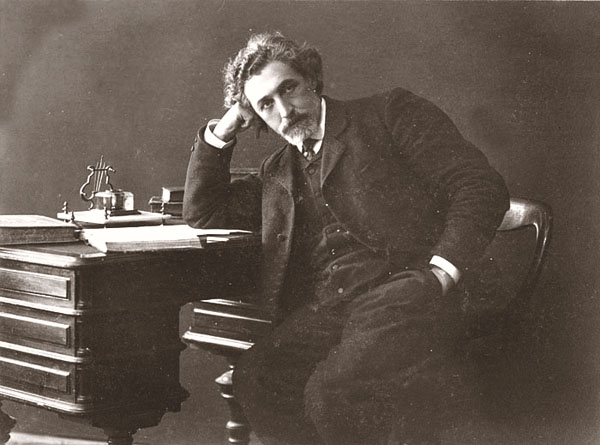

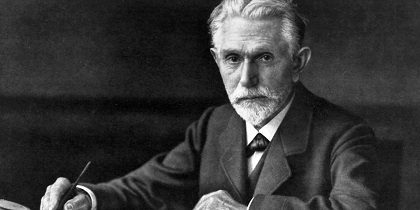

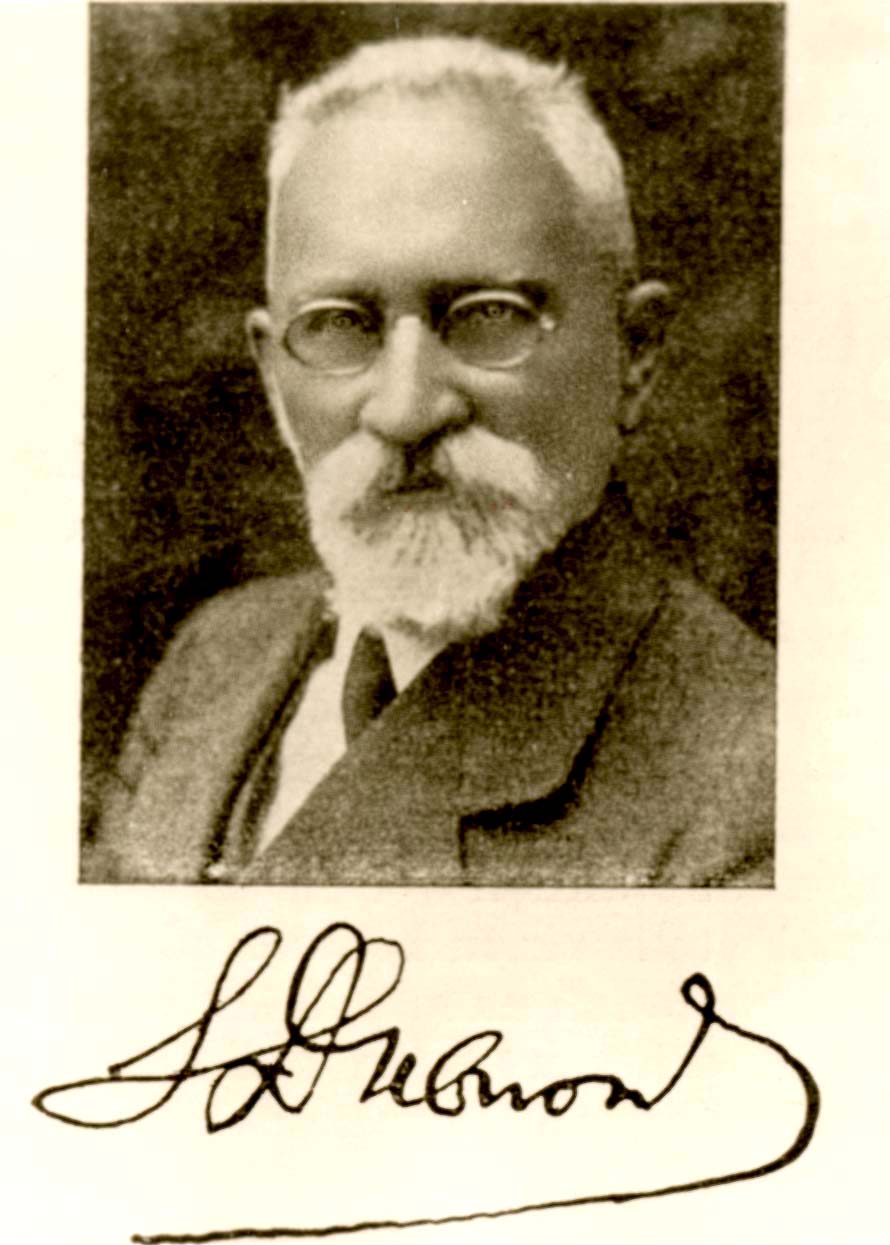

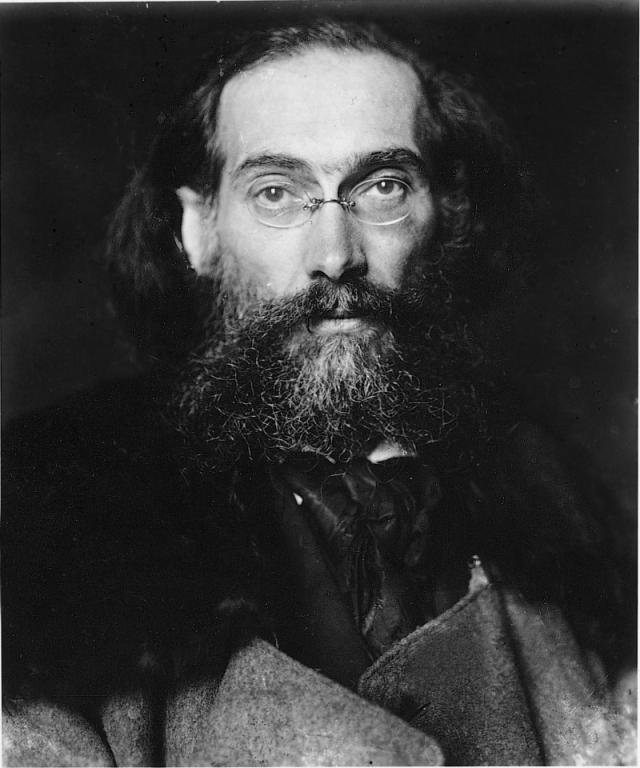

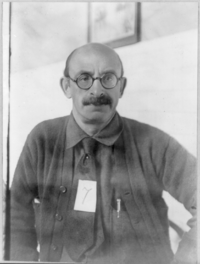

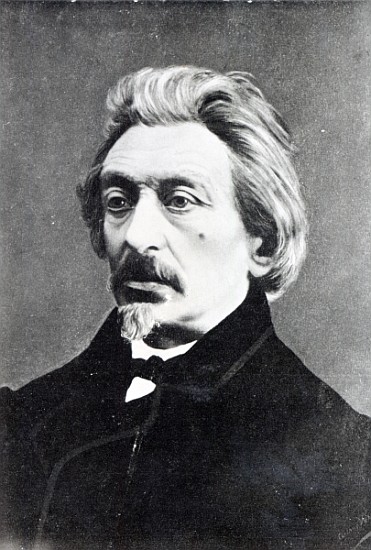

The Rise and Fall of the Jewish Labor BundNazism and Stalinism Delivered Blows; Ideology Did the Restby Philip MendesFrom the Autumn, 2013 issue of Jewish CurrentsThe Jewish Labor Bund The Rise and Fall of the Jewish Labor BundNazism and Stalinism Delivered Blows; Ideology Did the Restby Philip MendesFrom the Autumn, 2013 issue of Jewish CurrentsThe Jewish Labor Bund was one of the most important leftwing Jewish political organizations of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It played a key role in the formation of the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party well before its split into Menshevik and Bolshevik factions, and was influentially active in the 1905 Russian Revolution while emerging as a leader of Jewish self-defense against Tsarist pogroms. While the Russian wing of the Bund was destroyed by the Bolsheviks, the Polish Bund remained influential between the two world wars, and Bundist ideas traveled with Jewish emigrants to influence socialist movements throughout the world. Of course, the Holocaust eliminated the mass Jewish labor movement in Poland, and then the post-war Communist takeover destroyed the Bund politically. While the organization later regrouped as a world federation, it survives today as only a marginal movement in Jewish cultural and political life. Even its historical and political significance is recognized by only small numbers of Jews and progressives. Yet the Bund’s experience as an ethnic and class-based organization arguably encapsulates both the strengths and limitations of the historical, once-prominent Jewish engagement with socialist ideas and movements. The Bund was an internationalist organization that shared the core belief of all Marxist groups in a common class struggle aimed at achieving the liberation of all workers, whatever their national or religious origin. The Bund nevertheless insisted that Jews were a distinct national group, and that while Jewish workers should prioritize alliances with other socialists to advance the revolutionary cause, a separate Jewish socialist organization was required to adequately represent the national, cultural needs of working-class Jews in Eastern Europe. The Bund opposed assimilation, defended Jewish civil and cultural rights, and campaigned actively against anti-Semitism. However, the Bund’s socialist universalism precluded support for the notion of Jewish national unity ( klal yisrael) or for the narrow advancement of Jewish sectional interests. It eschewed any automatic solidarity with middle-or upper-class Jews, and generally rejected political collaboration with Jewish groups representing religious, Zionist or conservative viewpoints. The Bund’s famous anthem, known as “ The Oath” ( di shvue in Yiddish), composed by the Yiddish poet and cultural researcher Shloyme Zanvl Rappoport (1863 – November 8, 1920) in 1902, made no specific reference to Jews or Jewish suffering.  Shloyme Zanvl Rappoport (1863 – November 8, 1920), known by his pseudonym S. Ansky (or An-sky), was a Belarusian Jewish author, playwright, researcher of Jewish folklore, polemicist, and cultural and political activist. He is best known for his play The Dybbuk or Between Two Worlds, written in 1914. Ansky was also the author of the song Di Shvue (The Oath), which became the anthem of the Jewish Socialist Bund party. He was the author of the poem (later made into a song) "In Zaltsikn Yam" (In the Salty Sea), which was dedicated to the Bund as well. Shloyme Zanvl Rappoport (1863 – November 8, 1920), known by his pseudonym S. Ansky (or An-sky), was a Belarusian Jewish author, playwright, researcher of Jewish folklore, polemicist, and cultural and political activist. He is best known for his play The Dybbuk or Between Two Worlds, written in 1914. Ansky was also the author of the song Di Shvue (The Oath), which became the anthem of the Jewish Socialist Bund party. He was the author of the poem (later made into a song) "In Zaltsikn Yam" (In the Salty Sea), which was dedicated to the Bund as well. The Bund’s determination to be both militantly socialist and Jewish often left it politically isolated, accused of being ideologically purist and sectarian and unwilling to engage in pragmatic alliances with either moderate socialists or non-socialist Jews to achieve political power. Still, the Bund’s perspective arguably reflected the real experiences of its working-class constituency. Jews in Tsarist Russia and Poland between the wars were heavily divided by economic and social factors, with Jewish workers employed almost exclusively by Jewish employers, due to the anti-Semitism of their neighbors. As a result, the class struggle of Jewish workers was principally an internal Jewish class war. There was no united Jewish nation, and the Bund could not help seeing many Jews as the class enemy. The Bund was disappointed by the failure of broader socialist groups to display active solidarity with persecuted Jewish workers or with the Bund’s consistent internationalist values. Tensions between the Bund and the Polish Socialist Party as well as the Bolsheviks/Communists (under their various titles in Russia and Poland) reflected the Bund’s concern that the specific rights of Jewish workers were being subordinated either to Polish nationalist concerns or to wider socialist agendas. This was why the Bund remained organizationally independent of these larger movements. The Bund was formed in Lithuania, Poland, and Russia in 1897 — the same year as the first Zionist Congress in Basel, Switzerland — and initially demanded only equal civil rights for Jewish workers as individuals and an end to anti-Jewish discrimination. Over time, however, the Bund also sought recognition of Jewish national rights, though it remained unalterably opposed to Zionism. “ etween Zionist activity and Socialist activity,” declared Vladimir Medem, one of the Bund’s foremost ideological leaders, in 1920, “there is a fundamental and profound chasm. . . . A national home in Palestine would not end the Jewish exile. . . . All that would change would be the belief of Jewry in its future — the hope of the Jews in exile — the struggle for a better life would be snuffed out.”  Vladimir Medem, one of the Bund’s foremost ideological leaders Vladimir Medem, one of the Bund’s foremost ideological leadersIndeed, the Bund articulated the principle of doikayt (“ hereness”) — that is, the preservation of Jewish life and the struggle for liberation wherever Jews live — and advocated national-cultural autonomy for Jews within a multi-national state ( Poland). This perspective was concisely summarized as “ nationhood without statehood,” and differed sharply from the Zionist concept. The Bund achieved considerable success in its early years, and attracted an estimated 30,000 members by 1903 and 40,000 supporters by 1906, which made it the largest socialist group in the Russian Empire. The organization arguably reached the peak of its influence during the 1905 Russian revolution, when it demanded an improvement in living standards, a more democratic political system, and the introduction of equal rights for Jews. The organization was active in initiating mass strikes and demonstrations in cities with large Jewish populations such as Lodz, Riga, Vilna, Warsaw, Odessa, and Bialystok. The Bund also played a lead role in organizing and hosting the 1898 founding Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party ( RSDLP). However, the Bund’s relationship with the broader socialist movement collapsed five years later over the question of Jewish nationalism. At the 1903 RSDLP congress, the Bund sought formal recognition as the sole representative of the Jewish proletariat without geographical limits, and also proposed a federated party based on the multi-national model of the Austrian Socialists. The Bolshevik leader Vladimir Lenin vehemently rejected the notion of Jewish national culture, arguing that the concept was inherently reactionary and that the only solution to anti-Semitism was the progressive assimilation of Jews into the broader population. Ultimately, the Bund was forced to leave the RSDLP. Although Lenin agreed, for tactical reasons, to permit the re-entry of the Bund into the party in 1906 and to accept their claim to exclusive representation of Jewish workers, the Bolsheviks continued to reject the notion of Jewish national culture (as reflected in Joseph Stalin’s 1913 report, “ Marxism and the National Question”) and to accuse the Bund of fomenting separatist tendencies. During the February 1917 revolution, the Bund played an active part as allies of the Mensheviks. Leading Bundists such as Mark Liber, Raphael Abramovich, and Henryk Erlich held prominent positions in the various workers and soldiers’ councils known as soviets, and large numbers of Bundists were elected to local city councils. Following the Bolshevik takeover in October, a Bundist minority led by Vladimir Medem rejected Lenin’s rule as undemocratic and antipathetic to Jewish national rights, but the majority agreed to join the Communist Party. The Bund was then formally dissolved by the Bolsheviks in 1921, with remaining members either fleeing abroad or facing persecution by the Bolshevik regime. Mark Liber and many other Jewish Bundists would be executed in the Stalinist purges.  In Poland, on the other hand, the Bund voted in 1920 against accepting the twenty-one conditions for affiliation with the international communist body, the Comintern, which the Bund called, in a resolution, “ ideologically bankrupt” and playing “ a deleterious role in the labor movement.” Instead, the Bund affiliated with the Socialist or ( Social-Democratic) Second International, and established its own version of Jewish national-cultural autonomy in Poland, forming a large social, cultural and political Yiddish infrastructure that included trade unions, secular Jewish day schools, sporting associations, libraries, newspapers, youth and women’s groups, and health centres such as the famous Medem Sanatorium for children with tuberculosis. A video from 1936 of the famous Medem Sanatorium for children. Much of the personnel and children of the Sanatorium were transported to the extermination camp Treblinka in 1942. It is nearly hard to watch this Yiddish Bundist propagada video when you realise that a few years later most of these beautiful children were dead.Itzhak Luden, z"l – editor of Lebns-Fragn (Yiddish Bundist journal) – sings some of the parody songs written by children about the Medem Sanatorium, an educational institution for children at risk of tuberculosis run by the Yiddish secular school system in the interwar period.  Ukranian Bundists mourning members of their self-defense group who were killed in a 1905 anti-Tsarist uprising Ukranian Bundists mourning members of their self-defense group who were killed in a 1905 anti-Tsarist uprisingBy the mid-to-late 1930s, the Bund was the strongest Jewish political organization in Poland and secured major victories in Jewish communal and Polish municipal elections. One of the key reasons for the Bund’s strength was its active opposition to anti-Semitism, with public rallies, strikes, and self-defense groups that repositioned the Bund as representing the concerns of the broad Polish Jewish population rather than only a narrower swath of Jewish workers. To be sure, the Bund still rejected formal alliances with other Jewish political forces, Zionist or religious, but it joined with other progressive groups within Polish society to oppose anti-Semitism and seek the establishment of socialism. There would be “ no end to persecution [of Jews],” wrote the Bundist leader Victor Alter wrote in 1937, “ unless there is a simultaneous freeing of the Polish masses from social oppression. . . . Your liberation can only be a by-product of the universal freeing of oppressed people.”  During the Holocaust, the Bund remained reluctant to form specifically Jewish rather than broader socialist political alliances. Bundists also preferred to avoid any unified action with Communists. However, these principles clashed with political reality, given that the Nazis were uniquely targeting all Jews for genocide. With the Polish Socialist Party unable or unwilling to provide significant military assistance, the Bund eventually joined with Zionists, Communists, and other Jews to lead anti-Nazi resistance in a number of ghettos, including Warsaw, Vilna, and Bialystok. The Bund lost most of its members and supporters in the Holocaust. The Bundist member of the Polish Government-in-exile in London, Szmul (Artur) Zygielbojm, committed suicide to protest the world’s passivity about the extermination of the Jewish people. Surviving Bundists attempted to regroup in post-war Poland, but were suppressed by the Communist government. Most Bund leaders emigrated to other countries by early 1949.  Zygielboim’s suicide note Zygielboim’s suicide noteThe largest Bundist presence outside Central Europe was in the United States. The first Bund branch in America was established in 1900, and by 1904 a Central Union of Bund Organizations was formed to raise funds and organize lecture tours. During the 1905 Russian revolution, American Bundists raised $5,000 a week for several months to assist their colleagues in Russia. Bundists also played a major role in forming key American Jewish labor-movement parties, organizations, and Yiddish-language publications, including the still extant Workmen’s Circle and the Forward newspaper. Significant American labor leaders such as Sidney Hillman and David Dubinsky were Bundists. American Bundists also contributed significantly to the funding of Polish Bundist institutions; it has been estimated that American Bundists forwarded $91,000 to the Polish Bund between 1934 and 1939. Bundists played a lead role in forming the Jewish Labor Committee in 1934, to defend Jewish rights and counter the growth of Nazism. Headed by Baruch Charney Vladeck, the Committee provided emergency visas to European socialists ( mainly Jews, including many prominent Bundists who had found temporary refuge in Lithuania) to enable them to flee the Nazis. After World War II, the Committee helped Holocaust survivors rebuild their lives. It should be noted, however, that prior to World War II the Bund never constituted itself as an international Jewish socialist organization per se. Rather, the many Bund groups worldwide viewed themselves first and foremost as off-shoots of the Russian and later Polish Bund. It was only in 1947, following the Holocaust and the imminent dissolution of the Polish Bund, that Bund leaders in New York elected to form a World Coordinating Committee of Bundist Organizations. This new body vowed to defend Jewish economic and cultural concerns including the right to national identity. Even then, a significant minority opposed the decision to internationalize on the grounds of doikayt. The Bund’s ideological hostility towards all forms of Zionism lasted much longer than the anti-Zionism of many other socialist (and mainstream Jewish) groupings. One of the main reasons for this antipathy was that Bundists and Zionists competed for the same constituency in Russia and Poland. The Zionist movement’s advocacy of large-scale Jewish emigration to a proposed homeland in Palestine also clashed directly with the Bund’s insistence that anti-Semitism should be fought and defeated within all the countries in which Jews lived. More generally, the Bund’s universalist emphasis on the joint struggle of Jewish and non-Jewish workers could not be reconciled with the Zionist nationalist perspective in favor of the unity of all Jews. The Bund vigorously rejected large-scale Jewish emigration to Palestine and accused Zionists of failing to defend Jewish rights in Europe. They even argued that Zionists were collaborating with Polish anti-Semites who wished to force Jews to leave Poland. Palestine, they argued, was too small to accommodate large numbers of new emigrants — and it was not fair to impose a Jewish state on large numbers of Palestinian Arabs. Even after the Holocaust (albeit with some internal dissent), Bundists continued to campaign against Zionism. A Bundist conference held in 1948 shortly after the establishment of the State of Israel rejected that state as a solution to the problems of Jews worldwide, and instead called for a binational Jewish-Arab state in Palestine. Further Bundist statements castigated Zionism for its negation of Jewish communities outside Israel, and its rejection of Yiddish language and culture. However, the third world Bund conference, held in Montreal in 1955, adopted a more positive approach to Israel’s existence. Influenced by the development of an active Bundist movement inside Israel, the conference affirmed the significance of Israel while still rejecting the Zionist identification of Israel as the homeland of all Jews and the “ center” of Jewish life worldwide. Subsequent Bund statements supported the security and well-being of Israel while expressing criticisms of Israeli policies towards the Palestinians, criticisms similar to those adopted by the Israeli peace movement ( Gush Shalom ). ( en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gush_Shalom ) After World War II, the Bund attempted to rebuild itself in the key Jewish population centers of the U.S. and Western Europe, plus other outposts such as Australia, Mexico, Argentina, and, ironically, Israel. The full story of this renewal is told in the recently released book by Australian scholar David Slucki, The International Jewish Labor Bund After 1945 (New Brunswick, Rutgers University Press). This rebuilding, however, did not involve any significant revision of pre-war Bundist ideas and culture. Essentially the Bund attempted to impose Russian and Polish Jewish models on other Jewish communities, including those of Sephardi origin, rather than developing new ideas that reflected the social, political, and cultural experience of those communities. It is easy to argue that the Bund’s post-war marginalization was the inevitable result of the Holocaust and the subsequent Communist takeover of Poland. Additionally, the Bund was sidelined by the same post-war developments that undermined support for the Jewish Left more generally: the creation and consolidation of Israel as a central site for Jewish identity; the massive movement of Jews into the middle class, at least in the Western countries; the rapid shift in the Jewish vernacular from Yiddish to English, Hebrew and other local languages; the increasing Western tolerance towards Jews and the associated integration of most Jews into non-Jewish life and culture; and the rise of Soviet and broader anti-Semitism and anti-Zionism on the left. Yet the Bund’s fate also arguably confirmed the limitations of applying political ideals to only one specific state or territory. The Bund was never an internationalist movement of Jewish workers, but an organization tied closely to the specific language and political culture of Russia and Poland. Bundist organizations elsewhere served primarily as émigré groups offering a base of support for the movement in the “ home” countries. In simple terms, this meant that the death of the Jewish working class and the associated Yiddish cultural infrastructure in Poland inevitably signaled the end of the Bund as a significant political actor. In principle, the Bund could have reinvented itself as a world Jewish socialist body addressing specific Jewish living conditions and class issues in each country. A reformed Bund could have provided significant representation for working-class and other progressive Jews who did not conform to the new Jewish political consensus in favor of capitalist and Zionist values. This revision did not happen, however, in the post-war period — for the same reason that it did not happen after the earlier dissolution of the Russian Bund in 1920. It would have required a radical change in Bundist ideology from universal to nationalist, and a perspective of solidarity with Jews everywhere, including the large Jewish population living in Palestine and later Israel.  Philip Mendes is associate professor at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia, and the author or co-author of seven books, including Jews and Australian Politics (Sussex Academic Press, 2004). He is currently preparing Jews and the Left: The Rise and Fall of a Political Alliance for publication by Palgrave MacMillan in late 2013. Philip Mendes is associate professor at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia, and the author or co-author of seven books, including Jews and Australian Politics (Sussex Academic Press, 2004). He is currently preparing Jews and the Left: The Rise and Fall of a Political Alliance for publication by Palgrave MacMillan in late 2013. |

|

|

|

Post by pjotr on Dec 12, 2017 21:26:53 GMT 1

|

|

|

|

Post by pjotr on Dec 12, 2017 21:27:37 GMT 1

|

|

|

|

Post by pjotr on Dec 12, 2017 22:41:01 GMT 1

|

|

|

|

Post by pjotr on Dec 13, 2017 17:05:40 GMT 1

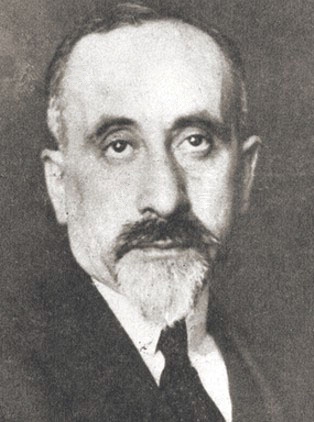

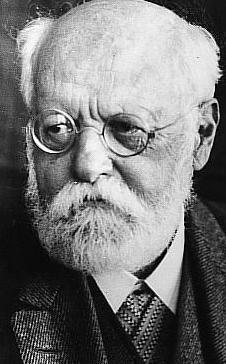

A part of the ideology of the Bund was Jewish Autonomism. It shared that philosophy or ideology with it's electoral competitor, the liberal Folkspartei ( yidishe folkspartei, ' Jewish People's Party', folkist party). Jewish Autonomism Simon DubnowJewish Autonomism Simon DubnowJewish Autonomism was a non-Zionist political movement that emerged in Central- and Eastern Europe in the late 19th and early 20th century. One of its major proponents was the historian and activist Simon Dubnow, who also called his ideology folkism. The Autonomists believed that the future survival of the Jews as a nation depends on their spiritual and cultural strength, in developing " spiritual nationhood" and in viability of Jewish diaspora as long as Jewish communities maintain self-rule, and rejected assimilation. Autonomists often stressed the vitality of modern Yiddish culture. Various concepts of Autonomism were adopted in the platforms of the Folkspartei, the Sejmists and socialist Jewish parties such as the Bund. Some groups blended Autonomism with Zionism: they favored Jewish self-rule in the diaspora until diaspora Jews make Aliyah to their national homeland in Zion ( British Palestine back then and Israel today). The movement's beliefs were similar to those of the Austromarxists, who advocated national personal autonomy within the multinational Austro-Hungarian empire, and cultural pluralists in America, such as Randolph Bourne and H orace Kallen. In 1941, Simon Dubnow was one of thousands of Jews murdered in the Rumbula massacre. After the Holocaust, the notion of Autonomism practically disappeared from Jewish philosophy. It is not connected to the contemporary political movement autonomism. |

|

|

|

Post by pjotr on Dec 13, 2017 17:35:26 GMT 1

Marshall Piłsudski greeted by Polish Orthodox jews Marshall Piłsudski greeted by Polish Orthodox jewsMany Polish jews by the way saw a protector in Józef Klemens Piłsudski at a time in which reactionary catholics, National Democrats (Endecja) and extreme rightwing Polish Falangists targeted jews verbally and sometimes physically. Piłsudski's regime began a period of national stabilization and of improvement in the situation of ethnic minorities, which formed about a third of the Second Republic's population. Piłsudski replaced the National Democrats' " ethnic-assimilation" with a " state-assimilation" policy: citizens were judged not by their ethnicity but by their loyalty to the state. Widely recognized for his opposition to the National Democrats' anti-Semitic policies, he extended his policy of " state-assimilation" to Polish Jews. The years 1926 to 1935 and Piłsudski himself were favorably viewed by many Polish Jews whose situation improved especially under Piłsudski-appointed Prime Minister Kazimierz Bartel. Many Jews saw Piłsudski as their only hope for restraining antisemitic currents in Poland and for maintaining public order; he was seen as a guarantor of stability and a friend of the Jewish people, who voted for him and actively participated in his political bloc. Piłsudski's death in 1935 brought a deterioration in the quality of life of Poland's Jews. Still Polish Jewish socialists and communists of the Bund and the rival of the Bund, the Komunistyczna Partia Polski ( KPP) ended up in prisons and prisoner camps, just like other opponents of the Sanacja regime (Conservatives, Nationalists and Polish fascists) for opposing the Sanation regime. That however didn't make Piłsudski less popular amongst Polish jews, because not every Polish jew was a Bundist or Communist. Many Polish jews were Polish democrats, conservatives or even supporters of the Sanacja party, the Nonpartisan Bloc for Cooperation with the Government (Polish: Bezpartyjny Blok Współpracy z Rządem, pronounced [bɛsparˈtɨjnɨ ˈblɔk fspuwˈpratsɨ z ˈʐondɛm]; abbreviated BBWR). |

|

|

|

Post by pjotr on Dec 13, 2017 18:14:12 GMT 1

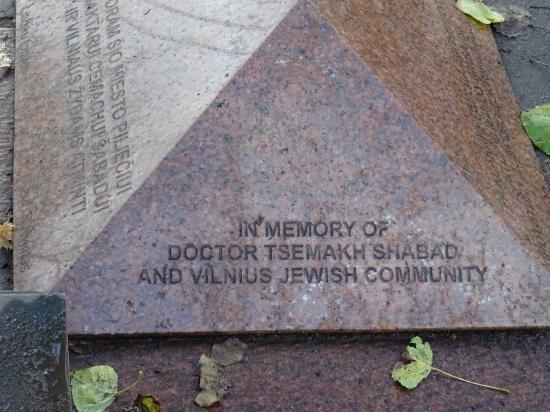

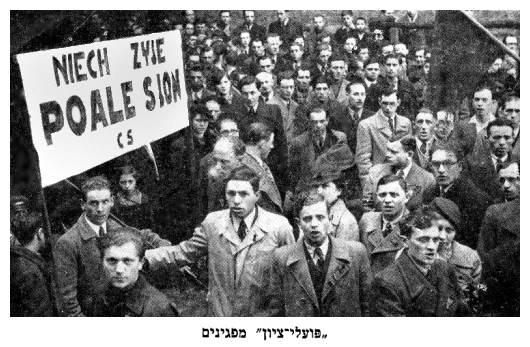

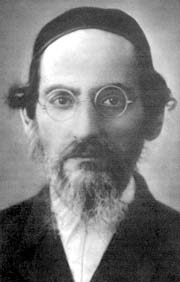

Other jewish political parties in pre-war Poland (1918-1939) were: Yidishe folkspartei The Folkspartei (Yiddish: ייִדישע פֿאָלקספּאַרטײַ, yidishe folkspartei, 'Jewish People's Party, folkist party) was founded after the 1905 pogroms in the Russian Empire by Simon Dubnow and Israel Efrojkin. The party took part in several elections in Poland and Lithuania in the 1920s and 1930s and did not survive the Shoah. Folkspartei in PolandA local organization and a newspaper, Warszawer Togblat ( The Warsaw Daily), was set up in Warsaw in 1916 in order to contend for the municipal elections (under German occupation), where they gained 4 seats, including Noach Pryłucki, one of the founders of the party's newspaper, later renamed as 'Der Moment'. He was also elected at the 1919 Constituent Sejm, but had to resign for a citizenship matter.  Noach (Nojach) Pryłucki or Noach Prilutski (October 1, 1882 in Berdichev – August 12, 1941 in Vilnius) was a Jewish Polish politician from the Folkspartei. He was also a Yiddish linguist, philologist, lawyer and scholar of considerable renown. Pryłucki was a respected attorney and was said to have had "leadership over the scattered (non-Zionist) national clubs, societies, and groups". Noach (Nojach) Pryłucki or Noach Prilutski (October 1, 1882 in Berdichev – August 12, 1941 in Vilnius) was a Jewish Polish politician from the Folkspartei. He was also a Yiddish linguist, philologist, lawyer and scholar of considerable renown. Pryłucki was a respected attorney and was said to have had "leadership over the scattered (non-Zionist) national clubs, societies, and groups".The party split in 1927 between the Warsaw branch, led by Pryłucki, and the Vilnius ( then a part of Poland) branch, led by Dr. Zemach Shabad, less hostile to Zionism than the Warsaw branch but more Yiddish-centered. After the split the party seems to have declined, with an attempt to revitalize it in Warsaw in 1935. At the 1936 Jewish community elections in Warsaw, the Folkspartei only got 1 seat out of 50, while the Bund got 15. In the 1922- 27 Polish Parliament ( Sejm) Noach Pryłucki was the only Folkist MP out of 35 Jewish MPs ( 25 Zionists, but no Bundist). He was elected on the list of the Bloc of National Minorities.  Zemach Shabad (Hebrew: צמח שאבאד, Polish: 'Cemach Szabad', Russian: Цемах Шабад, Tsemakh Shabad) (February 5, 1864, Vilnius, Russian Empire (now Lithuania) — January 20, 1935, Vilnius) was a Jewish doctor and social and political activist.[1] He was a member of the Senate (parliament) of the Second Polish Republic (1928) and a co-founder and vice-president of the YIVO (Institute for Jewish Research). Zemach Shabad (Hebrew: צמח שאבאד, Polish: 'Cemach Szabad', Russian: Цемах Шабад, Tsemakh Shabad) (February 5, 1864, Vilnius, Russian Empire (now Lithuania) — January 20, 1935, Vilnius) was a Jewish doctor and social and political activist.[1] He was a member of the Senate (parliament) of the Second Polish Republic (1928) and a co-founder and vice-president of the YIVO (Institute for Jewish Research).    He was one of the originators of the volkist movement, which eventually turned into the Folkspartei (Jewish People's Party). In 2007, Zemach Shabad was honored with a monument in Vilnius, reflecting the fact that he was the prototype of Doctor Aybolit, a good doctor from a poem for children by Korney Chukovsky. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/FolksparteiPoale Zion Members of the Wolbrom Left-wing Poale Zion group march in WarsawPoale Zion Members of the Wolbrom Left-wing Poale Zion group march in WarsawPoale Zion (also spelled Poalei Tziyon or Poaley Syjon, meaning " Workers of Zion") was a movement of Marxist–Zionist Jewish workers founded in various cities of Poland, Europe and the Russian Empire in about the turn of the 20th century after the Bund rejected Zionism in 1901.  “Poale Zion” protestingPoale Zion “Poale Zion” protestingPoale Zion was torn between Left and Right factions in 1919- 1920, which formally split at the Poale Zion fifth world congress in Vienna in 1920, following a similar division that occurred in the Second International.  Gathering of Poale Zion youth organisation in Ożarów, Poland 1926 Gathering of Poale Zion youth organisation in Ożarów, Poland 1926In Poland, for a brief period following the war, both factions of Poale Zion were reported as legal and functioning political parties. The Polish Left party was the largest Left Poale Zion party in the world. It worked closely with the Bund in developing Yiddish schools in Poland and supporting secular Yiddish culture, although they had political differences (e.g. the Bund was more supportive of the Polish Socialist Party than LPZ). [20] As part of the large-scale ban on Jewish political parties in post-war Poland by t he Communist leadership, both Poale Zion groups were disbanded in February 1950. pl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Poalej_Syjonen.wikipedia.org/wiki/Poale_ZionAgudath Israel Agudath Israel was an Orthodox Jewish political party in Poland which was loyal to the Polish government and opposed secularism, zionism, the Bund, the Folkspartei, Jewish communists and other secular jewish tendencies, movements and political parties. It began as a political party representing ultra-Orthodox Jews in Poland, originating in the Agudath Israel movement in Upper Silesia. World Agudath Israel was established by Jewish religious leaders at a conference held at Kattowitz (Katowice) in 1912. They were concerned that the Tenth World Zionist Congress had defeated a motion by the Torah Nationalists Mizrachi movement for funding religious schools. The aim of World Agudath Israel was to strengthen Orthodox institutions independent of the Zionist movement and Mizrachi organization. The advent of the First World War delayed development of the organisation, however. During the First World War, Rabbi Dr. Pinchas Kohn and Rabbi Dr. Emmanuel Carlebach (both from Germany), were appointed as the rabbinical advisors to the German occupying forces in Poland. In this position, they worked closely with the Grand Rabbi of Ger, Rabbi Avraham Mordechai Alter. As a result of this collaboration, they formed Agudath Israel, whose aim was to unify Eastern European and Western European Orthodox Judaism. Agudath Israel gained a significant following, particularly among Hasidic Jews. It had representatives running in the Polish elections after the First World War, and they won seats in that country's parliament ( Sejm). Among the elected representatives were Alexander Zusia Friedman, Rabbi Meir Shapiro, Rabbi Yosef Nechemya Kornitzer of Kraków, and Rabbi Aharon Lewin of Reysha.  Alexander Zusia Friedman Alexander Zusia Friedman Rabbi Meir Shapiro Rabbi Meir Shapiro Rabbi Yosef Nechemya Kornitzer of Kraków Rabbi Yosef Nechemya Kornitzer of KrakówProminent Torah scholars who led Agudath Yisroel included the Gerrer Rebbe, the Radziner Rebbe, Rabbi Mordechai Yosef Elazar Leiner, and the Chafetz Chaim.  Mordechai Yosef Elazar Leiner, Grand Rabbi of Radzin Mordechai Yosef Elazar Leiner, Grand Rabbi of RadzinThe ideology of the Agudath Yisroel was and is Torah, Torah Judaism, Haredi Judaism, Ashkenazi Haredim interests, Orthodox Halacha and Religious conservatism. Part of that ideology was being loyal to the Polish authorities, rejection of the policies of the Yiddish secular parties Folkspartei, Bund and Poale Zion and probably cooperation with the Sanacja regime and the Polish government before that (1919-1926) and after Sanacja. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/World_Agudath_IsraelOther Jewish movements inside Poland: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Betaren.wikipedia.org/wiki/Revisionist_Zionismen.wikipedia.org/wiki/General_Zionistsen.wikipedia.org/wiki/Labor_Zionism |

|

|

|

Post by pjotr on Dec 13, 2017 20:34:42 GMT 1