Post by Bonobo on Feb 16, 2018 15:32:57 GMT 1

Not just the boar...but also the guy and his house. He/it looks like something out of a fairy tale! He could be a woodman in one of Grimm's Fairy Tales!

Not just the boar...but also the guy and his house. He/it looks like something out of a fairy tale! He could be a woodman in one of Grimm's Fairy Tales! Not just the boar...but also the guy and his house. He/it looks like something out of a fairy tale! He could be a woodman in one of Grimm's Fairy Tales!

Not just the boar...but also the guy and his house. He/it looks like something out of a fairy tale! He could be a woodman in one of Grimm's Fairy Tales!

The description reads: Leszek Wilczek with Froggy, the wild boar, during breakfast.

kultura.onet.pl/sztuka/okres-prl-u-obfitowal-w-spektakularne-wydarzenia/v0gxf2t#slajd-3

He is an animal/nature lover, environmentalist, photographer, writer born in 1930 who moved to the privemal forest in 1971. He reared a lot of animals in his house. His surname in Polish means Wolf Cub.

pl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lech_Wilczek

The description reads: Leszek Wilczek with Froggy, the wild boar, during breakfast.

kultura.onet.pl/sztuka/okres-prl-u-obfitowal-w-spektakularne-wydarzenia/v0gxf2t#slajd-3

He is an animal/nature lover, environmentalist, photographer, writer born in 1930 who moved to the privemal forest in 1971. He reared a lot of animals in his house. His surname in Polish means Wolf Cub.

You have already met Lech Wilczek in another thread.

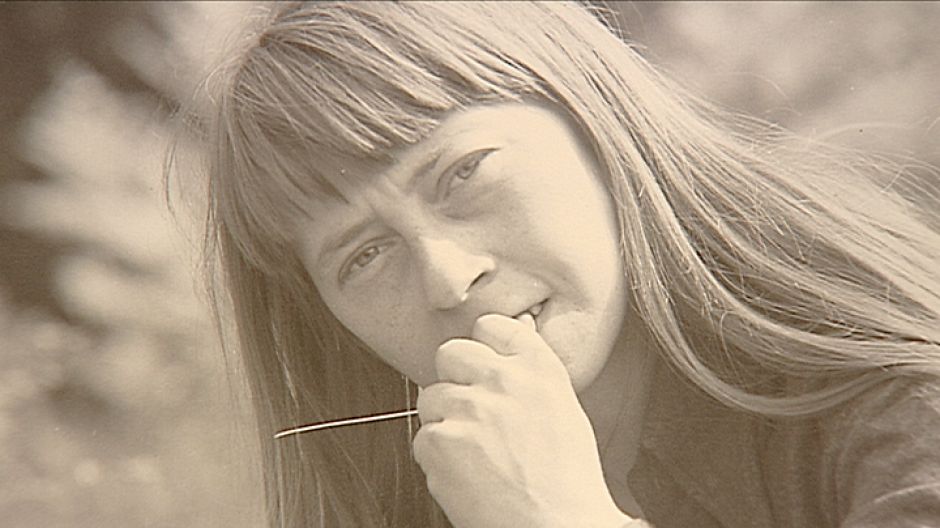

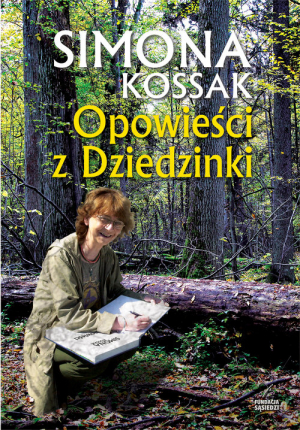

Now it is time to meet his friend, Simona Kossak, professor of biology and environmentalist, the daughter of a famous Polish painter. She died in 2007.

culture.pl/en/article/the-extraordinary-life-of-simona-kossak

Excerpts from the article:

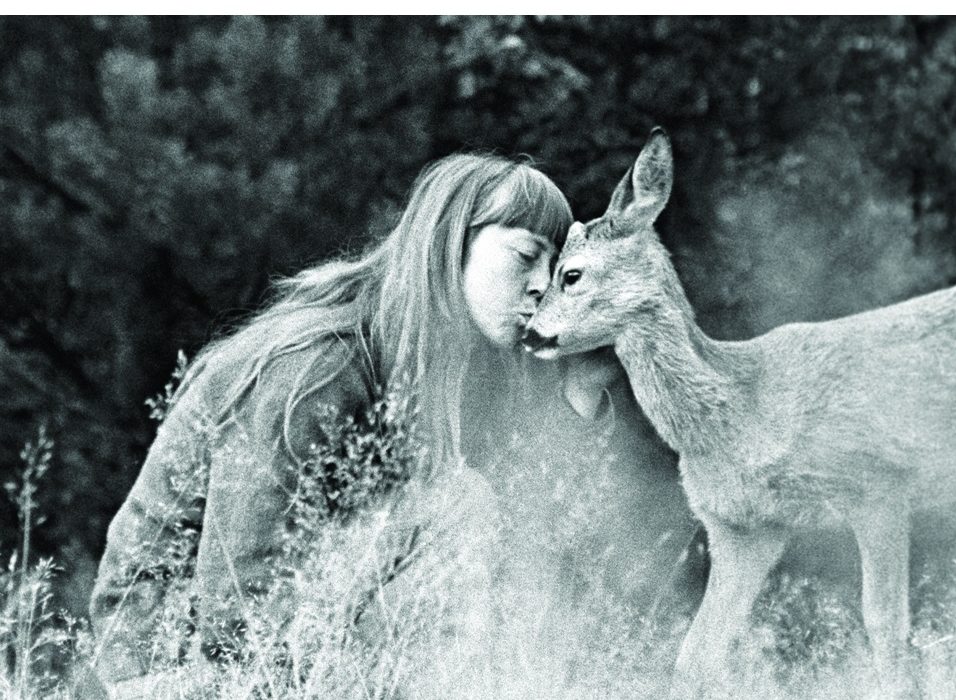

Simona Kossak: they called her a witch, because she chatted with animals and owned a terrorist-crow, who stole gold and attacked bicycle riders.

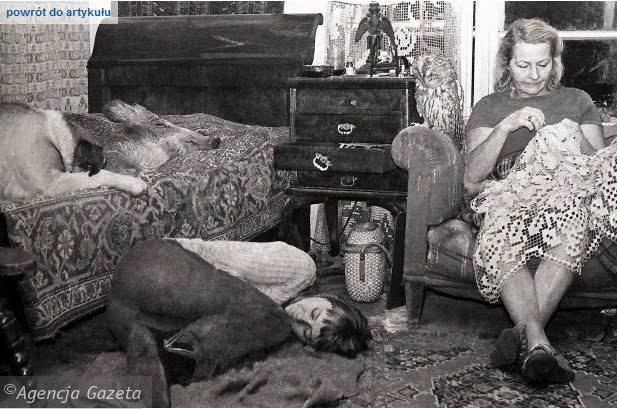

She spent more than 30 years in a wooden hut in the Białowieża Forest, without electricity or access to running water. A lynx slept in her bed, and a tamed boar lived under the same roof with her. She was a scientist, ecologist and the author of award-winning films, as well as radio broadcasts. She was also an activist who fought for the protection of Europe’s oldest forest. Simona believed that one ought to live simply, and close to nature. Among animals she found that which she never found with humans.

The great-granddaughter of Juliusz Kossak, granddaughter of Wojciech Kossak, and the daughter of Jerzy Kossak – three painters who loved both Polish landscapes and history. A niece of Maria Pawlikowska-Jasnorzewska and Magdalena Samozwaniec. She was meant to be a son and the fourth Kossak – carrying easels and her famous surname just like her ancestors. Instead, she chose a path of her own

"Simona first saw Dziedzinka in moonlight," Ewa Wysmułek remembers. "We decided we would go there at night time. The four of us went down the road with torches: my husband, a hired carter, myself, and Simona. Suddenly, an aurochs stepped out onto the Browska Road. The horse jibbed, we got scared, but we got there. Simona was enchanted with Dziedzinka straight away.” Years later, Simona described the expedition and the encounter with the king of the forest in the following words,

"It was the first aurochs that I ever saw in my life, I am not counting the ones in the zoo. Well, and this greeting right at the entry into the forest – this monumental aurochs, the whiteness, the snow, the full moon, whitey white everywhere, pretty (…) and the little hut hidden in the little clearing all covered with snow, an abandoned house that no one had lived in for two years. In the middle room, there were no floors, it was generally a ruin. And I looked at this house, all silvered by the moon as it was, romantic, and I said 'it’s finished, it’s here or nowhere else!'”

The boar, a one-day old female, was brought by Lech Wilczek and it was thanks to this animal that the two dwellers of Dziedzinka – Simona and Lech – go to know each other better. And they also came to like each other. Prior to this event, Simona thought Lech was too full of himself. He also had a similar opinion about her. When the boar appeared in Dziedzinka, Wilczek asked Simona to take care of her in his absence, and later he started to "lend" the animal out to her. Both later started to sleep with the little boar in their beds. Żabka grew to become an XXL sized boar, and she lived with them for 17 years. "She stood vigilantly by the leg like a dog, she went out on walks, and more and more often she cuddled up to the hosts and demanded to be caressed!,” exclaimed the Kraków-based journalist and a guest of Dziedzinka, Zbigniew Święch.

People called the crow a tamed villain and a thief. He terrorised half of the Białowieża area. He stole cigarette cases, hair brushes, scissors, cutters, mouse traps and notepads. He attacked people. (…) He tore up bicycle seats. He stole documents, he stole the lumberjacks’ sausage in the woods, and made holes in grocery bags. He clung at the pant legs of men, pulled at the skirts of women, and pricked the legs. People thought that Korasek – because that’s what he was called – was some kind of a punishment for sins. Stanisław Myśliński, who has scars from the bird to this day, recalls "He would even steal the workers’ pay in the woods. He once stole my permit for entering the woods. He pulled it out of my pocket and notoriously tore it apart. He loved to attack people who rode bicycles, especially girls. It was very impressive, he would attack the rider’s head with his beak, the person would fall off, and he then sat on the seat triumphantly, looking the at the spinning wheel”.

Simona recalled "One day, the pack of my deer, which I raised and fed with a bottle, and which I later followed across the woods for many years, manifested signs of fright, and did not want to go out onto the forest field to graze. And I started to approach the young forest, because this was the direction in which the deer started, their ears raised, and the hair standing up on their buttocks, apparently something very threatening had to be there in the young forest. I crossed about half of this open space and I stopped, because I heard a choir of terrified barking behind me, so I turned around, and what did I see? (…) Five of my deer stood up on their stiffly straightened legs, looking at me, and calling with this bark: don’t go there, don’t go there, there’s death over there! I must admit, I was dumbstruck, and then finally I did go. And what did I find? It turned out that there were fresh traces of a lynx that had crossed the young forest. I went in deeper, and I found lynx faeces, it was indeed warm, because I touched it. What did that mean? It meant that a carnivore had entered the farm, the deer noticed him, then ran and they were scared, and what did they see? They saw their mother going unto death, completely unaware, she had to be warned and for me, I will honestly admit, this day was a breakthrough. I crossed the border that divides the human world from that of the animals. If there was a glass that divided us from humans, a wall impossible to knock down, then the animals would not care about me. We are deer, she is human, what do we care for her? If they did warn me (…), it meant one thing and one thing only: you are a member of our pack, we don’t want you to get hurt. I honestly admit, I relived this event for many days, and in fact today, when I think about it, there is sense of warmth around my heart. It proves how one can befriend the world of wild animals.

With time, more animals appeared in Simona’s den by the house: a doe who approached the window and ate sugar, a black stork for whom Simona created a nest in a chest in her room, a dachshund and a female lynx that slept in the same bed with Simona, and peacocks. Dziedzinka quickly became an experimental laboratory which Simona consequently expanded as a zoo psychologist – with a hospital and a waiting room for sick animals. Here, she healed, hugged, and observed the animal lot together with Wilczek, who photographed them. Here, as a mother she raised moose twins, Pepsi and Cola, washed the neck of the black stork, took the female rat Kanalia into her sleeve (as the animal panicked in open spaces). She would let the befriended doe give birth on the patio, took in lambs with their mother, kept and observed the rats Alfa and Omega, and keep crickets in a glass container. It was here that she checked on weather by observing bats in the basement. The menagerie grew with each year (…).

In the winter of 1993, Simona commenced her battle for saving the lynxes and wolves of Białowieża from perdition. In an article for the Twój Styl magazine, Alina Niedzielska wrote for example that "A group of young workers from the Mammal Research Plant of the PAN Polish Academy of Sciences came up with the idea of telemetric studies. A wild animal is given a collar with a radio transmitter, so that it would pass out information as it walks about the woods. But the carnivore must first be caught. By coincidence, it was revealed that the researchers set up traps for the wolves and lynxes, which are prohibited by Polish law. Simona Kossak shows the 'research apparatus' that she came across in the forest – heavy metal jaws. It takes two men to open them up. She had just put away a ready typescript when a pack of wolves approached the house. (…) The wolves howled terribly. (…) "It was a gratuitous hymn for saving their lives,” she commented with conviction. "Wolves never approach buildings. They are too frightful. Perhaps they sensed the friendly aura emanating from the hut.” (…)

In 1993, within the strict natural reserve territory, Simona came across two metal jaw traps put up by the Mammal Research Plant team, so she took them with her and refused to give them back. She was accused by the scientist of stealing the research apparatus. The matter was investigated by the Regional Prosecution in Hojnówka and the 2nd Criminal Section of the Regional Court in Bielsko Podlaskie. During the hearing conducted by the Prosecution, in response to the question what kind of a threat such research apparatus in the Białowieża Forest presented to animals, Simona answered:

"In my opinion, it was a lethal threat not only to the animals, but also the guards. (…) Each animal that falls into the trap is potentially condemned to die if the wound to the paws is heavy. With a population that numbers twelve specimen, and including poaching and chance deaths of wild animals, it is a lethal threat to the continuity of the lowland lynx type, whose genetic scope is unique across all of Europe, because there are no more lowland lynxes in Europe. It is a disgrace to the world of science for us to have contributed to this.”

www.thegorgeousdaily.com/simona-kossak/