|

|

Post by tufta on Dec 28, 2008 8:58:42 GMT 1

Wielkopolska ("Greater Poland") is a region in Central Poland with a capital city of Poznań. Historically it is the craddle of Polish State, and the first Polish capital cities were in Wielkopolska. Later Poland grew in the South-Eastern direction, now called Małopolska (or Lesser Poland), with the capital of Krakow. Only then Mazowsze (or Mazovia) with Poland's final capital city of Warszawa which was for a long time partly independent from Poland, joined the Polish state.

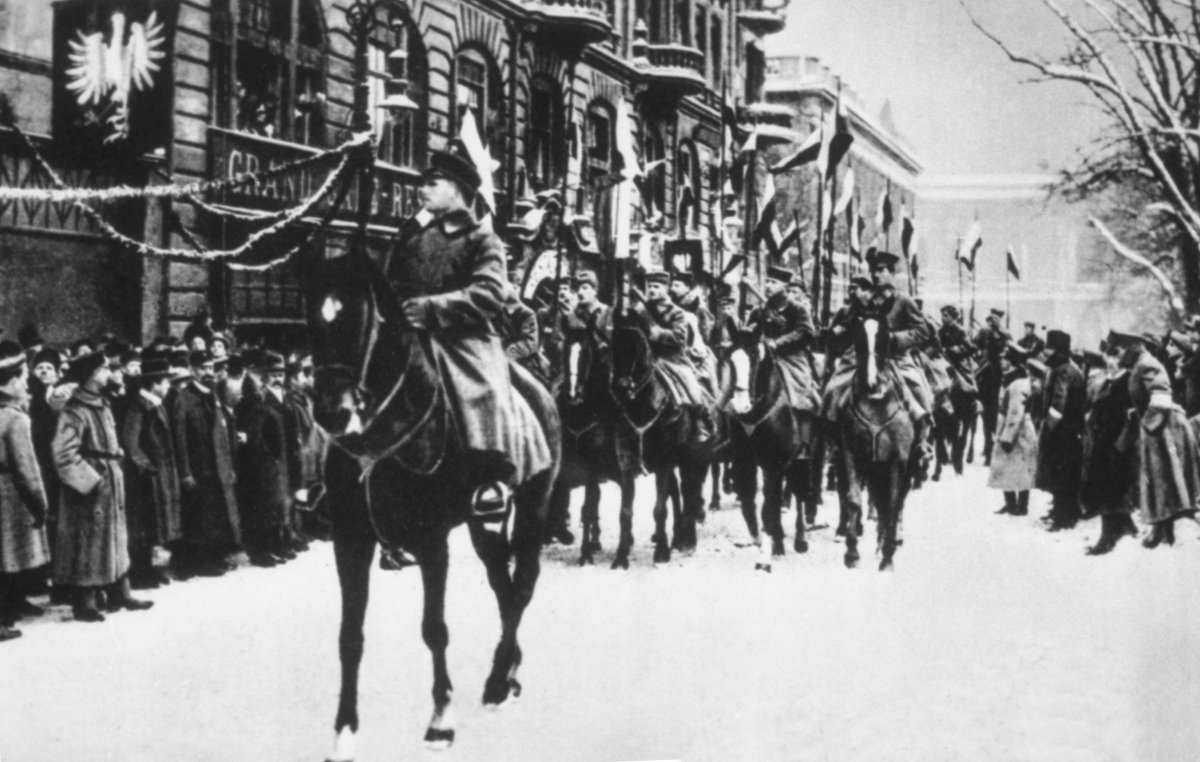

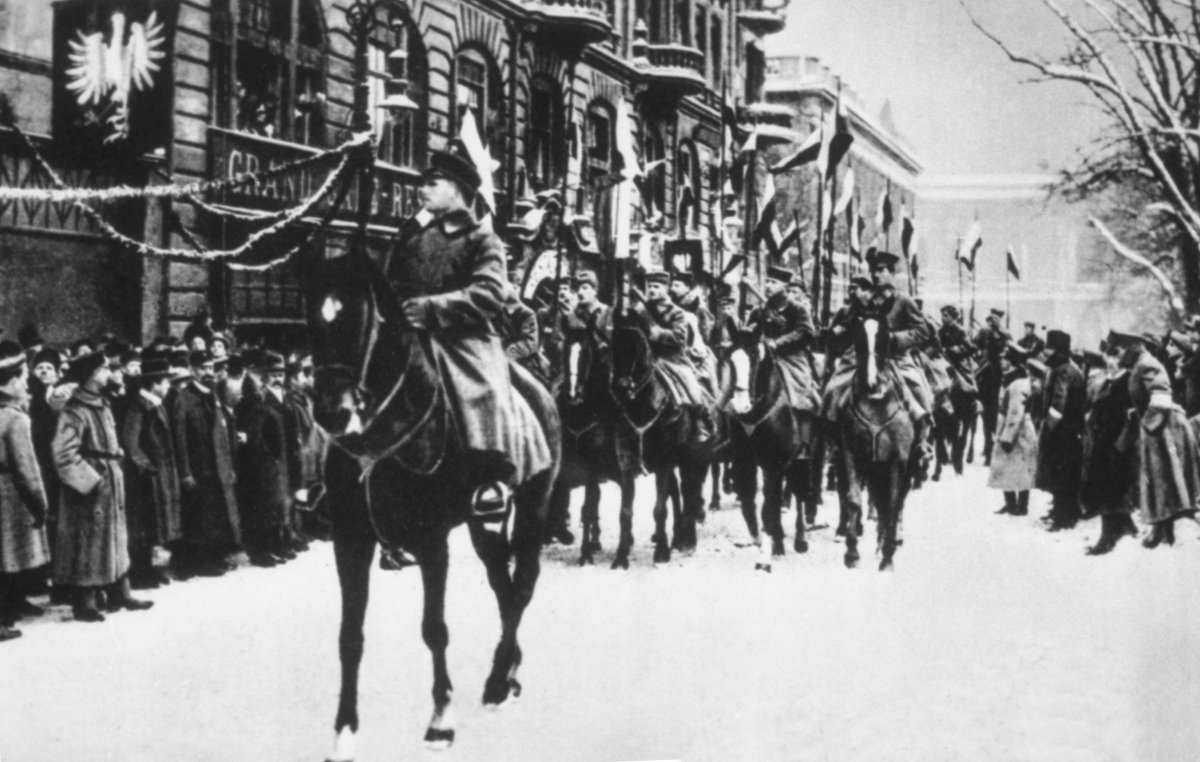

Wielkopolskie Uprising broke out on 27 December 1918, and is considered the most successful of Polish military struggles for freedom, as the uprising forces liberated Wielkopolska from German rule. As a result this region of Poland was ascribed to the motherland in the treaty of Versailles whch ended the First World War.

It is worth noting that people from Warsaw feel a special bond to Poznan, culturally and mentally we feel as 'twin cities'.

As part of the celebrations of the 90the anniversary of the Wielkopolskie Uprising , a 50-strong delegation from Poznań, central Poland, left for Warsaw to commemorate the fallen insurgents.

A group of representatives, including those of the local authorities and the Commemorative Association of the Greater Poland Uprising, have set out to retrace the historic journey of the insurgents, which took place one year before the outbreak of World War II. The group which had arrived in the capital seventy years ago laid flowers on the graves of those who died in the uprising and were buried in Powązki, the city’s oldest and most famous cemetery, and at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier.

President Lech Kaczyński, Prime Minister Donald Tusk, and the primate of Poland, Cardinal Józef Glemp have attended the ceremony in Poznań, which is soon to be followed by an open-air reenactment of the insurgency performed by over a hundred actors, dancers, and musicians.

|

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Dec 28, 2008 9:57:17 GMT 1

Good you started it. I was planning it too.... This was the only successful Rising by Poles. ( I don`t count another in 1806).

The Greater Poland Uprising of 1918–1919, or Wielkopolska Uprising of 1918–1919 (Polish: powstanie wielkopolskie 1918–19 roku; German: Großpolnischer Aufstand) or Posnanian War was a military insurrection of Poles in the Greater Poland region (also called the Grand Duchy of Poznań or Provinz Posen region) against Germany. The uprising had a significant effect on the Treaty of Versailles, which granted Poland the area won by the insurgents plus some additional territory.en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Greater_Poland_Uprising_(1918%E2%80%931919)

Background

Polish population as of 1918

After the 1795 Third Partition of Poland, Poland ceased to exist as an independent state. From 1795 through the beginning of World War I, several unsuccessful uprisings to regain an independent state took place. An 1806 uprising was followed by the creation of the Duchy of Warsaw which lasted for eight years before being partitioned again between Prussia and Russia.

At the end of World War I, U.S. President Woodrow Wilson's Fourteen Points met with opposition from European nations standing to lose power or territory. German politicians had signed an armistice leading to a cease fire on November 11, 1918, with the Western and former Eastern front lines outside of Germany. Many Germans felt they had not lost the war and felt betrayed by their leadership (Stab-in-the-back legend). Germany had signed the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk with Bolshevik Russia to settle the eastern frontiers. Therefore, from the date that the armistice was signed until the Treaty of Versailles was fully ratified in January 1920, many territorial and sovereignty issues remained unresolved.

Wilson's proposal for an independent Poland did not definitively set borders for Poland that could be universally accepted. Most of Poland partitioned to Prussia in the late 18th century was still part of Germany at the close of World War I with the rest of the subsequent post-WWI Polish being part of Russia and Austria-Hungary. The portion which was part of Germany included the Provinz Posen, or territory of Greater Poland, of which Poznań (Posen) was a major industrial city. The majority of the population was Polish (60%)[1] and was uncertain whether they would be repatriated with the proposed new Polish nation.

The uprising

In the autumn of 1918 Polish hopes for a sovereign Poland began serious preparations for an uprising after the Kaiser Wilhelm's abdication on 9 November 1918, which saw the end of the German monarchy, which would be replaced by the Weimar Republic.

The uprising broke out on 27 December 1918 in Poznań after a patriotic speech by Ignacy Paderewski, a famous Polish pianist.

The uprising forces consisted of members of the Polish Military Organization of the Prussian Partition, who started to form the Straż Obywatelska (Citizen's Guard), later renamed as Straż Ludowa (People's Guard) and many volunteers — mainly veterans of World War I. The ruling body was the Naczelna Rada Ludowa (High Peoples' Council) — at the beginning members of the Council were against the uprising, but supported it a few days later: unofficially 3 January 1919; officially 8 and 9 January 1919 — and the military commanders: Captain Stanisław Taczak (promoted to major, temporary commander 28 December 1918 – 8 January 1919) and later General Józef Dowbor-Muśnicki.

The timing of the uprising was fortuitous, as between October 1918 and the first months of 1919, internal conflict had weakened Germany, with soldiers and sailors rebelling against the monarchy and its hawkish generals. Demoralised by the signing of an armistice on November 11, 1918, Germany was embroiled in the German Revolution.

By 15 January 1919, the rebellious Polish forces managed to take control of most of the Province of Posen, and engaged in heavy fighting with the regular German army and the forces of the Grenzschutz, up until the renewal of the truce between the Entente and Germany on 16 February, which affected the Wielkopolska or Posen Province part of the front line. Skirmishes continued, however, until the signing of the Treaty of Versailles on June 28, 1919.

Many of the Wielkopolska insurgents also took part in the 1919 - 1921 uprisings in Silesia.

The Greater Poland Uprising is considered to be one of the two most successful Polish uprisings: the second was the Great Poland Uprising of 1806 which was ended by the entry of Napoleon's Army.

Although it never recovered the entire Prussian Partition, the uprising had a significant effect on the Versailles decisions, which granted Poland not only the area won by the insurgents but also a portion of the Province of Pomerania and the towns of Bydgoszcz, Leszno, and Rawicz (the Polish Corridor).

Germany's territorial losses as required by the Treaty of Versailles nonetheless incited German revanchism such that the status of the independent city-state Danzig (Gdańsk) and the Polish Corridor between East Prussia and the rest of Germany became a major issue in German politics, and was exploited by Adolf Hitler in his rise to power. Germany ultimately invaded Poland in September 1939, helping to spark World War II in Europe.

Poznan province in post WW1 Germany  Insurgents   Monuments  Modern re-enactment If you want to see the origin of the Rising and a final fighting scenes, get a Polish film: Męskie Sprawy. It beautifully renders the mood of Poles who are patiently waiting for the best moment to rise. In an amusing way the mature ones oppose young hot-heads but in the end all of them go to the battle. |

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Dec 28, 2008 22:08:28 GMT 1

Bo, it is great graphic 'didactic' material that you have provided. So not only you are a master of presentation in your own photos the things Polish (like the traditional orange tablecloth for instance hehehhe) but in the wider sense too! ;D Hmm, this flow of praise is really suspicious.... Tufta, say honestly, you want me to lend you some money?? ;D ;D ;D ;D ;D ;D Jokes aside! Thank you, but this is not the end. I have just started my visual presentation. As the topic is in a seperate thread, we can make it as big as we wish. And it is worth teaching Poles what a successful Rising should look like. Poles in the German occupation zone were really well-prepared. Paderewski arrives in Poznań.   Fights in the city  Fighting in trenches. Similarly to Warsaw Rising, Poles were using German equipment.  They didn`t get one bridge too far.  Insurgent troops liberate a Polish town

But casualties didn`t discourage others. More volunteers joined the insurgent troops.     Photos from this page www.powstaniewielkopolskie.pl/index.php?menu=historiaThe medal for brave participation

Anniversary ceremonies near the monument in 2007

|

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Dec 30, 2021 14:16:57 GMT 1

The Wielkopolskie Rising became a state holiday (not bank) this year.  Interesting interviews about the success of the Rising and two ghosts which still haunt Poland today: nationalist Dmowski`s and pro-multi-ethnic Piłsudski`s.

ONET WIADOMOŚCI POZNAŃ

The Greater Poland Uprising was victorious because it was done on time. The Marshal, but not Piłsudski, hit the table with his fist

- In Poland, we cherish the memory of defeats according to the Latin principle "gloria victis" - glory to the defeated. This can be seen, for example, in the still developed cult of "cursed soldiers" - emphasizes Dr. hab. Paweł Stachowiak from Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań, specialist in the recent history of Poland and the relationship between the Church and politics. Meanwhile, we have a victorious uprising, and the best known is the one that broke out in Poznań on December 27, 1918. This year it will be celebrated for the first time as a public holiday - the National Day of the Victorious Greater Poland Uprising.

Łukasz Cieśla

4.5 thousand

December 26, 2021, 13:20

In November 1918, unlike other regions, Greater Poland did not regain independence and remained under the Prussian partition. A few weeks later, the uprising broke out. The impulse was the arrival of the composer Ignacy Jan Paderewski to Poznań and his speech at the Bazar hotel

- The Greater Poland Uprising turned out to be victorious because it was the first mass uprising with the participation of the people, and above all it was done in time. The attitude of France also helped, as it hoped to further weaken its neighbor, the Germans, emphasizes prof. Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań, Paweł Stachowiak

For years, the inhabitants of Poznań had enormous claims against the head of state, Józef Piłsudski, for the lack of support for the uprising. They believed that he had betrayed Greater Poland. This is one of the reasons why, over the years, no monument to the creator of the independent Polish state has been erected in Poznań

The leader of the nationalists, Roman Dmowski, was much more sympathetic then. - Poznań was indeed an endockie, which is a shadow to this day, for example at the university where I work - adds Paweł Stachowiak

The old dispute between the supporters of Piłsudski and Dmowski, according to the historian from the Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań, is still valid today. - Józef Giedroyc's words that Poles live in the shadow of Piłsudski and Dmowski's coffins are still valid. Dmowski wanted a unitary and national state at the same time. Unfortunately, Poland is just such a country today - it is the triumph of Dmowski's coffin, next to which Jarosław Kaczyński stands, says Paweł Stachowiak

More information can be found on the main page of Onet.pl

Łukasz Cieśla: On December 27 we have a new public holiday. The National Day of the Victorious Greater Poland Uprising commemorates the events in Poznań at the end of 1918. Why is this victorious uprising only now acquiring a rank, and previously it was more widely unknown?

National Day of the Victorious Greater Poland Uprising. On December 27, we celebrate a new public holiday for the first time

Polish historical memory is strongly concentrated around Warsaw. It is enough to look at the period of World War II, or the partitions before that. Warsaw as the capital has become a point of reference for the collective memory of all Poles, which is evident in the works of mass culture. Let's look at the Warsaw Uprising, for example. After all, it had a local character, but the "W" hour engages practically all of us after many years.

In the case of the Greater Poland Uprising, its lower "popularity" was thus due to the fact that it had a regional, because it was Greater Poland, character. Of course, in recent years, efforts have been made to broaden the national awareness of this event, and the celebrations were also held in Warsaw, but they were held modestly there.

The Greater Poland Uprising was victorious, but our lost uprisings were more recorded in history books. Maybe it just did not fit the Polish myth of failure in a just cause?

Indeed, in Poland we cherish the memory of defeats according to the Latin principle "gloria victis" - glory to the defeated. The romantic cult of the fallen heroes has dominated our historical memory. Those who died in an unequal and losing battle, fought with no chance of victory, are admired, as can be seen, for example, in the still developed cult of "cursed soldiers".

Who were the cursed soldiers?

There was also a myth around the Greater Poland Uprising that it was the only winner. And yet it is not true. We are forgetting about the third Silesian Uprising of 1921.

This is undoubtedly a factual error, it was not the only victorious uprising. It was certainly the most famous of the uprisings won by Poles. There have been other victorious outbursts in history as well. In 1806, in connection with Napoleon's march to the east, the first Greater Poland uprising took place, which ended with a victory over the Prussian army. Over a hundred years later, in 1919, we had the victory of the Sejny Uprising in the Suwałki Region. This is a very little-known event - Poles won then against Lithuanians trying to dominate this area. And, of course, there were the second and third Silesian Uprisings, which were successful in political terms.

For years, people from Poznań were considered to be in order among the inhabitants of other regions, speaking Poznań as "regular", rather reluctant to romantic outbursts. How did it happen that they just managed to conduct a victorious uprising against a stronger army?

I will quote the leader of Polish emigration after the November Uprising, i.e. the uncrowned king of Poland, Prince Adam Czartoryski. He once said that Poland needed a general and timely uprising. This was the recipe for the success of the Greater Poland Uprising. It was the first popular uprising, I would say even plebeian, popular. Surrounded by the romantic fame of the 19th century uprising, that is, the November and January uprising, they were uprisings by the nobility. The people either did not join in or were even against them.

Only the Greater Poland Uprising involved the whole society. And the most important thing is that it was "done on time". Contrary to the previous ones, it broke out in external circumstances favorable to Poland. In December 1918, Germany was plunged into the extreme chaos of the socialist and communist revolution. Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg kept stirring up the revolutionary heat in Germany, the Social Democratic government did not control the situation. Apart from the broken Germans, we also had the support of France.

What did the French help us with?

Please take a look at what happened in Trier in February 1919. At that time, negotiations were taking place to extend the truce of November 11, 1918, ending the First World War. France, in the person of Marshal Ferdinand Foch, made it clear: the truce would be extended provided that the fighting in Greater Poland ended. The Germans resisted, and then Marshal Foch literally punched the table with his fist. Either Germany agrees to a truce in Greater Poland, or the war will continue.

In fact, Germany had no choice but to suspend the fighting in Greater Poland. This is where we come to the main reason for the success of the Greater Poland Uprising. If it had lasted longer, the Germans would probably have found the strength to put down the Polish rebellion militarily. In the spring of 1919, they prepared a counteroffensive, but before that, a truce was concluded in Trier.

Prof. Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań, Paweł StachowiakProf. UAM Paweł Stachowiak - Archive

The Greater Poland Uprising is of great importance for the region to this day, it is a symbol intended to emphasize the uniqueness of the victorious Wielkopolanie, famous for their organic work. And how did it influence the fate of Poland?

If you look at it in terms of the history and effects of those events, the uprising that broke out on December 27, 1918 was of an absolutely supra-local nature. It did not penetrate the consciousness of Poles, and thanks to him, Poland gained Greater Poland, an important region both historically and economically.

Perhaps, had it not been for the uprising, the region would have been awarded to Poland anyway during the conference in Paris in 1919. However, the control of this territory by the insurgents certainly made it easier for the Western powers to make a decision favorable to Poland. Thanks to this, Poland became an independent state composed of all three partitions, which seemed to be completely impossible before the First World War.

After the end of World War I, it was not so obvious that Greater Poland would become part of independent Poland. When in Warsaw on November 11, 1918, independence was celebrated and Marshal Józef Piłsudski was celebrated, Poznań and Greater Poland were still in the Prussian partition.

At the beginning of 1918, American President Thomas Woodrow Wilson, in his famous address to Congress on war goals, said in the thirteenth point that an independent Poland should be established, within ethnic borders, with free access to the sea. In principle, it was known that if the coalition with the Americans won, we would regain our sovereignty. Of course, it was unknown to what limits and what the access to the sea was supposed to look like. President Wilson thought rather about providing Poles with access to the port in Gdańsk by making the Vistula run internationally.

There was no chance that Wielkopolska would find itself in independent Poland in November 1918?

The entire Prussian partition, including Pomerania, was still then formally part of the German state. Weak, but within certain limits. The uprising that broke out in Poznań and Greater Poland on December 27 was, in some respects, then an internal rebellion in Germany.

This is what the British, who in 1918 warned Józef Piłsudski against interfering in Germany's internal affairs, seem to have seen it.

This is how the British saw it then, and so did some Americans. Polish interests, obviously not out of exaggerated love for us, were most supported by the aforementioned French, who counted on further weakening of neighboring Germany. Therefore, at the end of 1918, the fate of Greater Poland was indeed uncertain. Besides, some of the Greater Poland elite was also not convinced of the armed struggle, there were voices that it was better to wait for a peace conference and deal with the region's affairs in diplomatic talks. If that happened, I think that not all of Greater Poland would necessarily end up in independent Poland.

In November 1918, Józef Piłsudski came to Warsaw. On November 11, he became the head of the Polish army. He became the de facto head of state and the hero of collective consciousness as the creator of independent Poland. However, in Poznań he had a poor press - Wielkopolanie believed that he had betrayed them and did not support the efforts for independence. Does this black legend of Piłsudski have any basis?

I will quote a quote from Marshal Piłsudski from January 1919, when the uprising was already underway. He then stated that in the west, i.e. in Greater Poland and Pomerania, we do not have much to do. The powers will decide here. We will get as much as others agree and to what extent, as he put it, the powers will want to "tighten" Germany.

But in the east, he added, the situation is different. There are doors that open and close, and it depends on us how much we will be able to open them by force. Thus, he was of the opinion that the emerging Poland was too weak to engage in conflicts on two fronts at the same time. Efforts must be concentrated where one can act independently, i.e. in the east. He did not want to expose Poland to a war with Germany.

But Wielkopolska was not less important to him. This was just how he analyzed the international situation and the possibilities of our young state at the time. He has drawn conclusions - whether it is correct that is another matter - that one should get involved on the eastern border.

There are allegations that he got along with the Germans and traded Wielkopolska. When he was released from the fortress in Magdeburg in November 1918, he was to promise them that he would not fight for Wielkopolska by armed forces.

He told Count Harry Kessler, who came to him in Magdeburg as a representative of the new German government, that the current generation of Poles would not start a war with Germany over Poznań. There was no promise that Poland would forget about this region, but that it would not start a quick war. At that time, his attitude resulted from the view that the young state should focus on the east.

Besides, let's remember that that conversation took place while he was in prison. He was saying this at a time when the question of his release from the fortress in Magdeburg was contemplated. As a political player, he said this to ensure his freedom. Therefore, in that conversation, I would not see any betrayal or calculation forever and ever.

The aversion to Piłsudski, however, persisted in Greater Poland for the following years. Apparently, in the early 1930s, when he was in Poznań, the townspeople cheered "Józef, Józef". When Piłsudski was overjoyed, the crowd was told to say "ale Haller".

(laughs) It happened. Piłsudski, to put it mildly, was greeted coolly in Poznań. In fact, Poznań has become the only larger city where there is still no monument to him. When the May coup d'état in 1926 took place, the concept of secession even appeared in Greater Poland. Fortunately, nothing came of it.

Those differences have faded over the years, today they are more of an element of socio-political folklore than a burning ideological dispute. After all, almost a hundred years have passed. Emotions are blurring, and education and mass culture have a diminishing effect on past animosities. Nevertheless, anyone who comes to Poznań from another city in Poland and is interested in history will notice the absence of the Piłsudski monument and the lack of a larger street named after him.

In 2019, a monument to Józef Piłsudski was erected in Rzeszów.In 2019, a monument to Józef Piłsudski was erected in Rzeszów. - Darek Delmanowicz / PAP

To what extent was the aversion to Piłsudski influenced by the fact that the interwar Poznań was to a large extent a town from the Endek region? The nationalists and their leader Roman Dmowski, who lived near Poznań for some time, were very popular here.

Poznań was indeed an endecki, which is a shadow to this day, for example at the university where I work. It was the University of Poznań, also due to the influence of the National Democratic Party, that was the first university in Poland to introduce the "numerus clausus" principle at that time. The idea was to limit the number of students of Jewish origin. There were plans, and here too, the leader of the university in Poznań, to introduce the principle of "numerus nullus", that is, to completely eliminate Jews from the student body. There were many other anti-Semitic excesses.

Over the years, those embarrassing events have not been studied. Only now is there a special commission at AMU to thoroughly investigate and settle the past. And the case arose in 2019, on the occasion of the centenary of the University of Poznań.

The recent march of nationalists in Kalisz was not an excess at all

Since that period is only now being investigated, the old words of Józef Giedroyc are valid that Poles live in the shadow of two coffins: Piłsudski and Dmowski? Do you see analogies between contemporary Poland and that of a hundred years ago?

Giedroyc's words, perhaps indirectly, remain valid. Józef Piłsudski and Roman Dmowski, former antagonists, are historical figures. Probably less known to the younger generation. But let's look at their way of defining the nation. Is the nation an ethnic group, a blood community, or a civic community? Today we have a division in Poland around what a nation is and who we include in the community.

The blood community is the heritage of Dmowski and the National Democratic Party. The civic community is the legacy of Piłsudski and his political camp. Dmowski wanted a unitary and national state at the same time, realizing the interests of Poles understood in an ethnic way. Other nations were to have only the status of a national minority. Unfortunately, Poland is just such a country today - it is the triumph of Dmowski's coffin. On the other hand, Piłsudski wanted a state unconnected with any ethnic community, and his federal concept assumed the existence of one great civil nation consisting of various nations and ethnos.

Many may feel surprised now, but a great supporter of such an idea of civic and not ethnic Polishness was John Paul II. In his last book, Memory and Identity, he identified the nation with culture and wrote: "Polishness is essentially plurality and pluralism, not narrowness and closure. It seems, however, that this Jagiellonian dimension of Polishness has, unfortunately, ceased to be something obvious in our times." .

Are you saying that John Paul II was a Piłsudski man?

(laughs) I would not say that, but in my opinion, in his views on the nation, the state, and in his mental formation, John Paul II was much more a Piłsudski than a National Democrat. It was due to the entire romantic tradition in which it was formed. Without a doubt.

The PiS president, Jarosław Kaczyński, also referred to the Piłsudski tradition, but on the other hand - in his views on the nation - he stands at Dmowski's coffin. Do you judge it like that too?

President Lech Kaczyński was certainly a supporter of the Piłsudski tradition. He did it in an absolutely conscious way, for example through his Eastern policy, which was in fact Promethean, rooted in Piłsudski's ideas. In many respects, he was also closer to the idea of the independence left, the tradition of the PPS. As for Jarosław Kaczyński, even if he declares his attachment to Piłsudski, which I have not seen recently, in a mental sense he is much closer to Dmowski.

This can be seen in his view of the nation, the state, and his approach to the Church. It presents a certain ideological ossification and distortion, less and less pragmatism in the PiS president. Unfortunately for us and ours it becomes more and more ideological. So two twin brothers stood by different coffins. And maybe for the Marshal, the company of Lech Kaczyński in the Wawel crypt of silver bells is not so unpleasant, the more frequent visits of his brother ...

And if you asked me about Donald Tusk, I would certainly not see him at Dmowski's coffin, although perhaps they both share a cult of pragmatism and a kind of political realism.

November 2018, Jarosław Kaczyński and PiS politicians at the Roman Dmowski monument in WarsawNovember 2018, Jarosław Kaczyński and PiS politicians at the Roman Dmowski monument in Warsaw - Piotr Nowak / PAP

President of PiS at the Dmowski monument as the Head of State

The coffins of Piłsudski and Dmowski will still rule us?

And it's still a long time. Many Poles do not need to know the views of these two politicians, but they still think either of Piłsudski or Dmowski, completely unaware of it. Once upon a time, Piłsudski and Dmowski, perhaps like now Tusk and Kaczyński, hit the tender and at the same time different strings of Polish national character, tradition and identity. The sound of these strings will continue.

We are glad that you are with us. Subscribe to the Onet newsletter to receive the most valuable content from us

ŁC

Łukasz Cieśla

Date Created: December 26, 2021, 13:20

|

|