|

|

Post by jeanne on Dec 4, 2018 0:29:59 GMT 1

PS. "Poland means nowhere" Please explain what you mean by that...I have no clue as to what you are talking about!  |

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Dec 4, 2018 9:28:43 GMT 1

PS. "Poland means nowhere" Please explain what you mean by that...I have no clue as to what you are talking about!  It is a quote from an old French drama. It is hard to explain what the author meant because the drama genre is grotesque. But if we keep in mind what grotesque style implies, then nowhere means everywhere.   |

|

|

|

Post by jeanne on Dec 4, 2018 18:28:39 GMT 1

Please explain what you mean by that...I have no clue as to what you are talking about!  It is a quote from an old French drama. It is hard to explain what the author meant because the drama genre is grotesque. But if we keep in mind what grotesque style implies, then nowhere means everywhere.   Hmmm...I'll have to think about that for awhile... |

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Dec 6, 2018 21:48:37 GMT 1

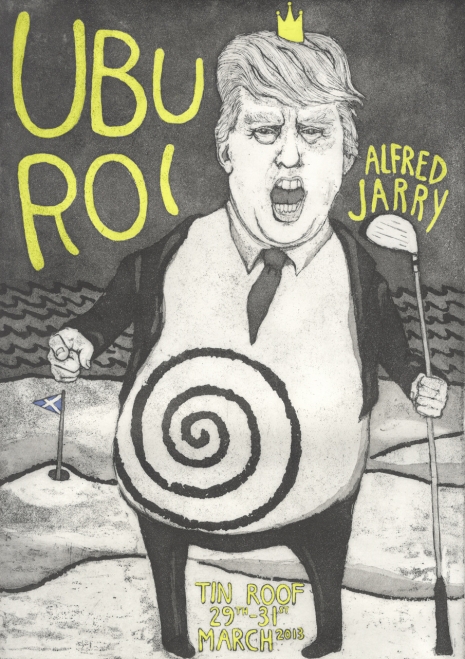

It is a quote from an old French drama. It is hard to explain what the author meant because the drama genre is grotesque. But if we keep in mind what grotesque style implies, then nowhere means everywhere.   Hmmm...I'll have to think about that for awhile... Well, I didn`t read the drama nor see the theatre performance, regularly staged here and there. It is popular in Poland due to absurd plot. Polish writers and playwrights used to employ absurd and grotesque in their works, probably somehow inspired by the French author who is credited for inventing the genre. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ubu_Roi

Ubu Roi (Ubu the King or King Ubu) is a play by Alfred Jarry. It was first performed in Paris at the Théâtre de l'Œuvre, causing a riotous response in the audience as it opened and closed on December 10, 1896.[1][2] It is considered a wild, bizarre and comic play, significant for the way it overturns cultural rules, norms, and conventions. For those who were in the audience on that night to witness the response, including W. B. Yeats, it seemed an event of revolutionary importance. It is now seen by some to have opened the door for what became known as modernism in the twentieth century.[3] It is a precursor to Dada, Surrealism and the Theatre of the Absurd. It is the first of three stylised burlesques in which Jarry satirises power, greed, and their evil practices—in particular the propensity of the complacent bourgeoisie to abuse the authority engendered by success.

Synopsis

The story is a parody of Shakespeare's Macbeth and some parts of Hamlet and King Lear. Though the writing and dialogue is obscene and childish, the material began to express something deeper, an inner consciousness in a way that is similar to the Symbolists, with many critics considering Jarry a Symbolist author.[1][9]

As the play begins, Ubu's wife convinces him to lead a revolution, and kills the King of Poland and most of the royal family. The King's son, Bougrelas, and the Queen escape, but the latter later dies. The ghost of the dead king appears to his son and calls for revenge. Back at the palace, Ubu, now King, begins heavily taxing the people and killing the nobles for their wealth. Ubu's henchman gets thrown into prison; who then escapes to Russia, where he has the Tsar to declare war on Ubu. As Ubu heads out to confront the invading Russians, his wife tries to steal the money and treasures in the palace. She is driven away by Bougrelas, who is leading a revolt of the people against Ubu. She runs away to her husband, Ubu, who has, in the meantime, defeated the Russians, abandoned by his followers and been attacked by a bear. Ubu's wife pretends to be the angel Gabriel, in order to try to scare Ubu into forgiving her for her attempt to steal from him. They fight, and she is rescued by the entrance of Bougrelas, who is after Ubu. Ubu knocks down the attackers with the body of the dead bear, after which he and his wife flee to France, which ends the play.

The action contains motifs found in the plays of Shakespeare: a king's murder and a scheming wife from Macbeth, the ghost from Hamlet, Fortinbras' revolt from Hamlet, the reneging of Buckingham's reward from Richard III, and the pursuing bear from The Winter's Tale. It also includes other cultural references, for example, to Sophocles' Oedipus Rex (Œdipe Roi in French) in the play's title. Ubu Roi is considered a descendent of the comic grotesque French Renaissance author François Rabelais and his Gargantua and Pantagruel novels.[10][11]

The language of the play is a unique mix of slang code-words, puns and near-gutter vocabulary, set to strange speech patterns.Penderecki made it into an opera www.nytimes.com/1991/07/08/news/review-opera-long-delayed-munich-premiere-ubu-rex-from-penderecki.htmlNot that Mr. Penderecki's score was all that tricky. Ingeniously constructed but rhythmically square and almost defiantly charmless, it subjects this tale to a kind of dry, hectoring rant. Some Penderecki champions have already called it his homage to Rossini, but that does the Italian an injustice. The better music comes in the second of the two roughly hour-long acts, in which Mr. Penderecki's penchant for veiled quotation runs more rampant. Some of the citations are from his own religious works, which at least lend the Russian scenes a flavorful aura.dangerousminds.net/comments/king_turd_absurdist_play_president_trump

According to Jane Taylor, “The central character is notorious for his infantile engagement with his world. Ubu inhabits a domain of greedy self-gratification.” Jarry’s metaphor for the modern man, he is an antihero—fat, ugly, vulgar, gluttonous, grandiose, dishonest, stupid, jejune, voracious, cruel, cowardly and evil—who grew out of schoolboy legends about the imaginary life of a hated teacher who had been at one point a slave on a Turkish Galley, at another frozen in ice in Norway and at one more the King of Poland. Ubu Roi follows and explores his political, martial and felonious exploits, offering parodic adaptations of situations and plot-lines from Shakespearean drama, including Macbeth, Hamlet and Richard III: like Macbeth, Ubu—on the urging of his wife—murders the king who helped him and usurps his throne, and is in turn defeated and killed by his son; Jarry also adapts the ghost of the dead king and Fortinbras’s revolt from Hamlet, Buckingham’s refusal of reward for assisting a usurpation from Richard III and The Winter’s Tale‘s bear.

“There is,” wrote Taylor, “a particular kind of pleasure for an audience watching these infantile attacks. Part of the satisfaction arises from the fact that in the burlesque mode which Jarry invents, there is no place for consequence. While Ubu may be relentless in his political aspirations, and brutal in his personal relations, he apparently has no measurable effect upon those who inhabit the farcical world which he creates around himself. He thus acts out our most childish rages and desires, in which we seek to gratify ourselves at all cost.” The derived adjective “ubuesque” is recurrent in French and francophone political debate.

|

|