Post by pjotr on May 30, 2016 20:05:38 GMT 1

Jewish Warsaw

Demographically, Warsaw was the most diverse city in Poland, with significant numbers of foreign-born inhabitants. In addition to the Polish majority, there was a significant Jewish minority in Warsaw. According to Russian census of 1897, out of the total population of 638,000, Jews constituted 219,000 (around 34% percent). Warsaw's prewar Jewish population of more than 350,000 constituted about 30 percent of the city's total population. In 1933, out of 1,178,914 inhabitants 833,500 were of Polish mother tongue.

According to a census of 1901, out of 711,988 inhabitants there were 56.2% Catholics, 35.7% Jews, 5% Greek orthodox Christians and 2.8% Protestants. Eight years later, in 1909, there were 281,754 Jews (36.9%), 18,189 Protestants (2.4%) and 2,818 Mariavites (0.4%).

An ever-increasing proportion of Jews in interwar Poland lived separate lives from the Polish majority. In 1921, 74.2% of Polish Jews listed Yiddish or Hebrew as their native language; the number rose to 87% by 1931, resulting in growing tensions between Jews and Poles. Jews were often not identified as Polish nationals, a problem caused not only by the reversal of assimilation shown in national censuses between 1921 and 1931, but also by the influx of Russian Jews escaping persecution—especially in Ukraine, where up to 2,000 pogroms took place during the Civil War, an estimated 30,000 Jews were massacred directly, and a total of 150,000 died. A large number of Russian Jews emigrated to Poland, as they were entitled by the Peace treaty of Riga to choose the country they preferred. Several hundred thousand refugees joined the already numerous Jewish minority of the Polish Second Republic. The resulting economic instability was mirrored by anti-Jewish sentiment in some of the media; discrimination, exclusion, and violence at the universities; and the appearance of "anti-Jewish squads" associated with some of the right-wing political parties. These developments contributed to a greater support among the Jewish community for Zionist and socialist ideas, coupled with attempts at further migration, curtailed only by the British government. Notably, the "campaign for Jewish emigration was predicated not on antisemitism but on objective social and economic factors". However, regardless of these changing economic and social conditions, the increase in antisemitic activity in prewar Poland was also typical of antisemitism found in other parts of Europe at that time, developing within a broader, continent-wide pattern with counterparts in every other European country.

With the influence of the Endecja party growing, antisemitism gathered new momentum in Poland and was most felt in smaller towns and in spheres in which Jews came into direct contact with Poles, such as in Polish schools or on the sports field. Further academic harassment, such as the introduction of ghetto benches, which forced Jewish students to sit in sections of the lecture halls reserved exclusively for them, anti-Jewish riots, and semi-official or unofficial quotas (Numerus clausus) introduced in 1937 in some universities, halved the number of Jews in Polish universities between independence (1918) and the late 1930s. The restrictions were so inclusive that – while the Jews made up 20.4% of the student body in 1928 – by 1937 their share was down to only 7.5%, out of the total population of 9.75% Jews in the country according to 1931 census.

Although many Jews were educated, they were excluded from most of the government bureaucracy. A good number therefore turned to the liberal professions, particularly medicine and law. In 1937 the Catholic trade unions of Polish doctors and lawyers restricted their new members to Christian Poles (in a similar manner the Jewish trade unions excluded non-Jewish professionals from their ranks after 1918). The bulk of Jewish workers were organized in the Jewish trade unions under the influence of the Jewish socialists.

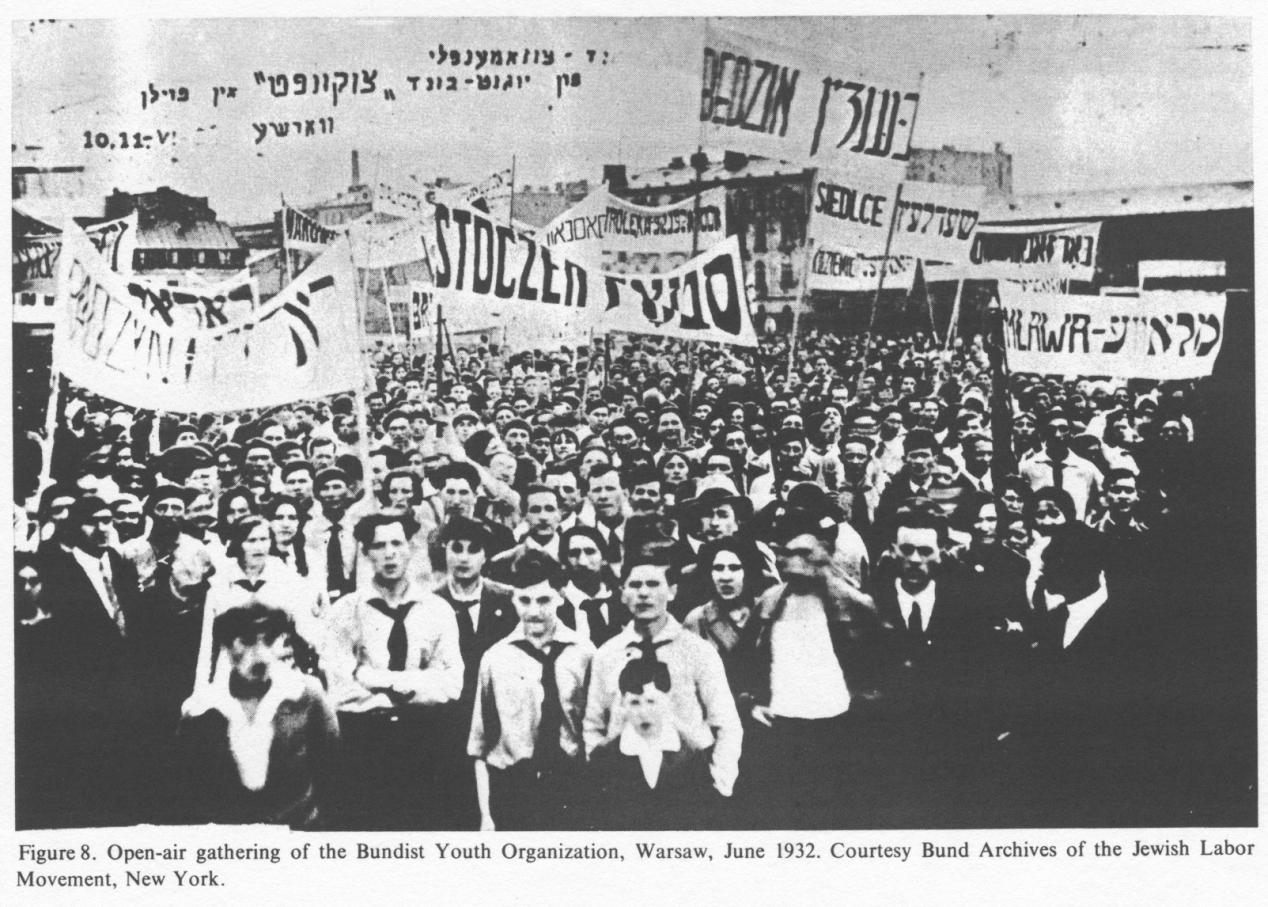

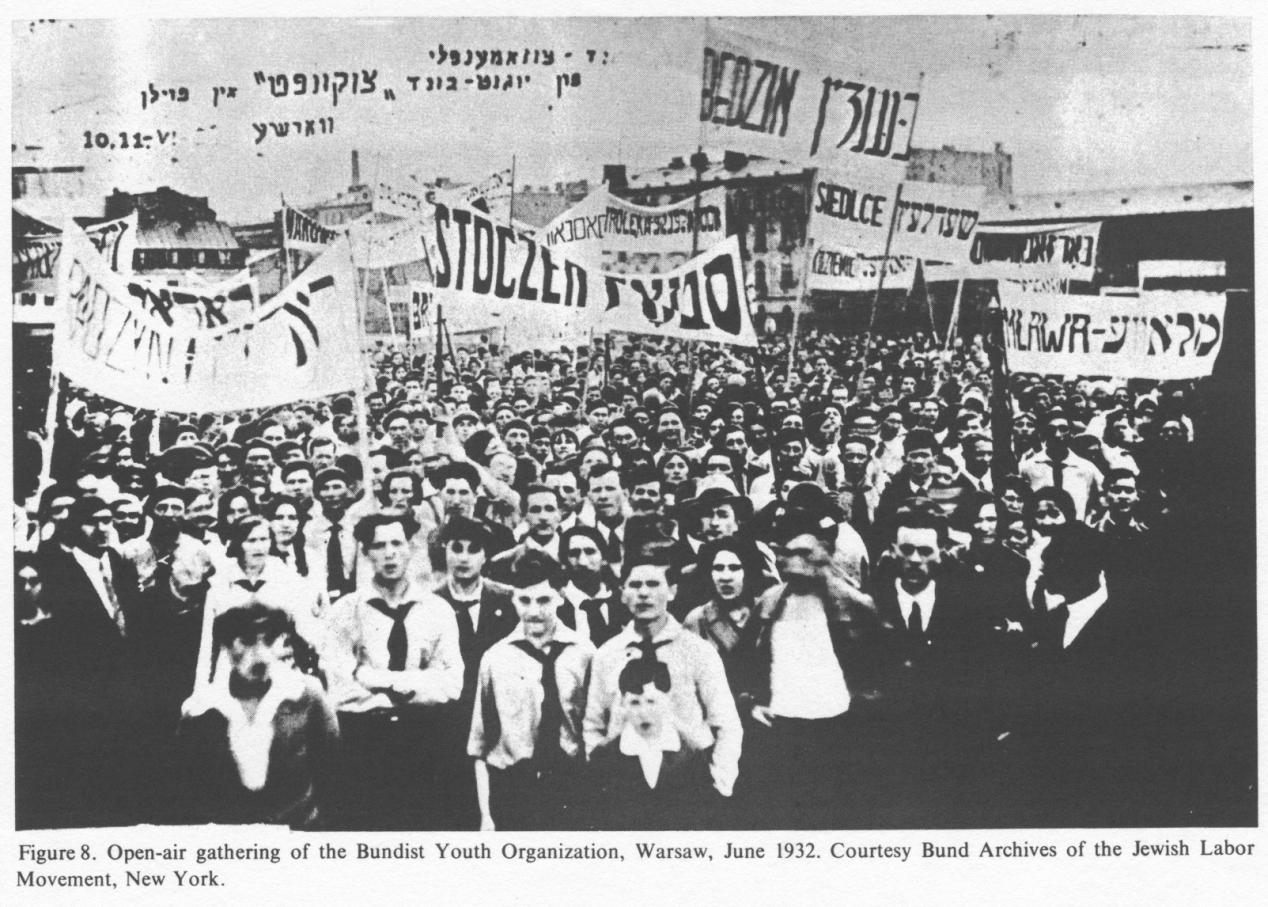

Many Polish Jewish workers, students, youngsters, children and progressive members of the Jewish middle class joined the General Jewish Labour Bund in Poland (Yiddish: אַלגעמײַנער ײדישער אַרבעטער בּונד אין פוילין tr:Algemeyner yidisher arbeter bund in poyln, Polish: Ogólny Żydowski Związek Robotniczy), often symply called Bund. Bund was a Jewish socialist party in Poland which promoted the political, cultural and social autonomy of Jewish workers, sought to combat antisemitism and was generally opposed to Zionism.

Contrary to the other Jewish parties, the Bund advocated an electoral cooperation with other Socialists, and not just between either Jewish parties or with other minority parties (in the electoral alliance "Bloc of National Minorities"). Thence, the Orthodox Jewish Agudat Israel (who was loyal to the Polish government according to their religious practices), Folkspartei ( Yiddish: ייִדישע פֿאָלקספּאַרטײַ, yidishe folkspartei, 'Jewish People's Party, folkist party) and the various Zionist parties were represented in the Sejm, but the Bund never was, mostly because its potential partner, the Polish Socialist Party (PPS), was reluctant to appear as a pro-Jewish party.

In December 1938 and January 1939, at the last Polish municipal elections before the start of the Second World War, the Bund received the largest segment of the Jewish vote. In 89 towns, one-third elected Bund majorities.[15] In Warsaw, the Bund won 61.7% of the votes cast for Jewish parties, taking 17 of the 20 municipal council seats won by Jewish parties. In Łódź the Bund won 57.4% (11 of 17 seats won by Jewish parties).[16] For the first time, the Bund and the PPS had agreed to call their electors to vote for each other where only one of them presented a list. This however did not go so far as common electoral lists. This alliance made it possible for a Left electoral victory in most great cities: Warsaw, Łódź, Lwow, Piotrkow, Kraków, Białystok, Grodno, Vilnius.

The number of Jews in Poland on September 1, 1939 amounted to about 3,474,000 people. One hundred thirty thousand soldiers of Jewish descent served in the Polish Army at the outbreak of the Second World War, thus being among the first to launch armed resistance against the Nazi Germany. It is estimated that during the entirety of World War II as many as 32,216 Polish-Jewish soldiers and officers died and 61,000 were taken prisoner by the Germans; the majority did not survive. The soldiers and non-commissioned officers who were released ultimately found themselves in the Nazi ghettos and labor camps and suffered the same fate as other Jewish civilians in the ensuing Holocaust in Poland.

In 1939, Jews constituted 30% of Warsaw's population. With the coming of the war, Jewish and Polish citizens of Warsaw jointly defended the city, putting their differences aside. Polish Jews later served in almost all Polish formations during the entire World War II, many were killed or wounded and very many were decorated for their combat skills and exceptional service. Jews fought with the Polish Armed Forces in the West, in the Soviet formed Polish People's Army as well as in several underground organizations and as part of Polish partisan units or Jewish partisan formations.

In many places in the city the Jewish culture and history resonates down through time. Among them the most notable are the Jewish theater, the Nożyk Synagogue, Janusz Korczak's Orphanage and the picturesque Próżna Street. The tragic pages of Warsaw’s history are commemorated in places such as the Monument to the Ghetto Heroes, the Umschlagplatz, fragments of the Ghetto wall on Sienna Street and a mound in memory of the Jewish Combat Organization.

New arrivals to Warsaw celebrate the Passover seder in a shelter on 6 Leszno St.

There are also many places commemorating the heroic history of Warsaw. Pawiak, an infamous German Gestapo prison now occupied by a Mausoleum of Memory of Martyrdom and the museum, is only the beginning of a walk in the traces of Heroic City.

Another important monument, the statue of Little Insurgent located at the ramparts of the Old Town, commemorates the children who served as messengers and frontline troops in the Warsaw Uprising, while the impressive Warsaw Uprising Monument by Wincenty Kućma was erected in memory of the largest insurrection of World War II. The few jews who surived the Warsaw Ghetto uprising of 1943 engaged in the Warsaw uprising together with their Polish-Roman Catholic compatriots.

P.S.- I hope that Bonobo can ad something about Polish-Jewish coexistence, shared battle or conservation of Jewish heritage in Poland. The very little things I know is that there were some mixed Polish-Jewish marriages in my Polish family, in the sense of Roman-Catholic/jewish marriages. The grandmother of a Polish cousin of mine was jewish. But she lived a Roman-Catholic life with her husband.

Demographically, Warsaw was the most diverse city in Poland, with significant numbers of foreign-born inhabitants. In addition to the Polish majority, there was a significant Jewish minority in Warsaw. According to Russian census of 1897, out of the total population of 638,000, Jews constituted 219,000 (around 34% percent). Warsaw's prewar Jewish population of more than 350,000 constituted about 30 percent of the city's total population. In 1933, out of 1,178,914 inhabitants 833,500 were of Polish mother tongue.

According to a census of 1901, out of 711,988 inhabitants there were 56.2% Catholics, 35.7% Jews, 5% Greek orthodox Christians and 2.8% Protestants. Eight years later, in 1909, there were 281,754 Jews (36.9%), 18,189 Protestants (2.4%) and 2,818 Mariavites (0.4%).

An ever-increasing proportion of Jews in interwar Poland lived separate lives from the Polish majority. In 1921, 74.2% of Polish Jews listed Yiddish or Hebrew as their native language; the number rose to 87% by 1931, resulting in growing tensions between Jews and Poles. Jews were often not identified as Polish nationals, a problem caused not only by the reversal of assimilation shown in national censuses between 1921 and 1931, but also by the influx of Russian Jews escaping persecution—especially in Ukraine, where up to 2,000 pogroms took place during the Civil War, an estimated 30,000 Jews were massacred directly, and a total of 150,000 died. A large number of Russian Jews emigrated to Poland, as they were entitled by the Peace treaty of Riga to choose the country they preferred. Several hundred thousand refugees joined the already numerous Jewish minority of the Polish Second Republic. The resulting economic instability was mirrored by anti-Jewish sentiment in some of the media; discrimination, exclusion, and violence at the universities; and the appearance of "anti-Jewish squads" associated with some of the right-wing political parties. These developments contributed to a greater support among the Jewish community for Zionist and socialist ideas, coupled with attempts at further migration, curtailed only by the British government. Notably, the "campaign for Jewish emigration was predicated not on antisemitism but on objective social and economic factors". However, regardless of these changing economic and social conditions, the increase in antisemitic activity in prewar Poland was also typical of antisemitism found in other parts of Europe at that time, developing within a broader, continent-wide pattern with counterparts in every other European country.

With the influence of the Endecja party growing, antisemitism gathered new momentum in Poland and was most felt in smaller towns and in spheres in which Jews came into direct contact with Poles, such as in Polish schools or on the sports field. Further academic harassment, such as the introduction of ghetto benches, which forced Jewish students to sit in sections of the lecture halls reserved exclusively for them, anti-Jewish riots, and semi-official or unofficial quotas (Numerus clausus) introduced in 1937 in some universities, halved the number of Jews in Polish universities between independence (1918) and the late 1930s. The restrictions were so inclusive that – while the Jews made up 20.4% of the student body in 1928 – by 1937 their share was down to only 7.5%, out of the total population of 9.75% Jews in the country according to 1931 census.

Although many Jews were educated, they were excluded from most of the government bureaucracy. A good number therefore turned to the liberal professions, particularly medicine and law. In 1937 the Catholic trade unions of Polish doctors and lawyers restricted their new members to Christian Poles (in a similar manner the Jewish trade unions excluded non-Jewish professionals from their ranks after 1918). The bulk of Jewish workers were organized in the Jewish trade unions under the influence of the Jewish socialists.

Many Polish Jewish workers, students, youngsters, children and progressive members of the Jewish middle class joined the General Jewish Labour Bund in Poland (Yiddish: אַלגעמײַנער ײדישער אַרבעטער בּונד אין פוילין tr:Algemeyner yidisher arbeter bund in poyln, Polish: Ogólny Żydowski Związek Robotniczy), often symply called Bund. Bund was a Jewish socialist party in Poland which promoted the political, cultural and social autonomy of Jewish workers, sought to combat antisemitism and was generally opposed to Zionism.

Contrary to the other Jewish parties, the Bund advocated an electoral cooperation with other Socialists, and not just between either Jewish parties or with other minority parties (in the electoral alliance "Bloc of National Minorities"). Thence, the Orthodox Jewish Agudat Israel (who was loyal to the Polish government according to their religious practices), Folkspartei ( Yiddish: ייִדישע פֿאָלקספּאַרטײַ, yidishe folkspartei, 'Jewish People's Party, folkist party) and the various Zionist parties were represented in the Sejm, but the Bund never was, mostly because its potential partner, the Polish Socialist Party (PPS), was reluctant to appear as a pro-Jewish party.

In December 1938 and January 1939, at the last Polish municipal elections before the start of the Second World War, the Bund received the largest segment of the Jewish vote. In 89 towns, one-third elected Bund majorities.[15] In Warsaw, the Bund won 61.7% of the votes cast for Jewish parties, taking 17 of the 20 municipal council seats won by Jewish parties. In Łódź the Bund won 57.4% (11 of 17 seats won by Jewish parties).[16] For the first time, the Bund and the PPS had agreed to call their electors to vote for each other where only one of them presented a list. This however did not go so far as common electoral lists. This alliance made it possible for a Left electoral victory in most great cities: Warsaw, Łódź, Lwow, Piotrkow, Kraków, Białystok, Grodno, Vilnius.

The number of Jews in Poland on September 1, 1939 amounted to about 3,474,000 people. One hundred thirty thousand soldiers of Jewish descent served in the Polish Army at the outbreak of the Second World War, thus being among the first to launch armed resistance against the Nazi Germany. It is estimated that during the entirety of World War II as many as 32,216 Polish-Jewish soldiers and officers died and 61,000 were taken prisoner by the Germans; the majority did not survive. The soldiers and non-commissioned officers who were released ultimately found themselves in the Nazi ghettos and labor camps and suffered the same fate as other Jewish civilians in the ensuing Holocaust in Poland.

In 1939, Jews constituted 30% of Warsaw's population. With the coming of the war, Jewish and Polish citizens of Warsaw jointly defended the city, putting their differences aside. Polish Jews later served in almost all Polish formations during the entire World War II, many were killed or wounded and very many were decorated for their combat skills and exceptional service. Jews fought with the Polish Armed Forces in the West, in the Soviet formed Polish People's Army as well as in several underground organizations and as part of Polish partisan units or Jewish partisan formations.

In many places in the city the Jewish culture and history resonates down through time. Among them the most notable are the Jewish theater, the Nożyk Synagogue, Janusz Korczak's Orphanage and the picturesque Próżna Street. The tragic pages of Warsaw’s history are commemorated in places such as the Monument to the Ghetto Heroes, the Umschlagplatz, fragments of the Ghetto wall on Sienna Street and a mound in memory of the Jewish Combat Organization.

New arrivals to Warsaw celebrate the Passover seder in a shelter on 6 Leszno St.

There are also many places commemorating the heroic history of Warsaw. Pawiak, an infamous German Gestapo prison now occupied by a Mausoleum of Memory of Martyrdom and the museum, is only the beginning of a walk in the traces of Heroic City.

Another important monument, the statue of Little Insurgent located at the ramparts of the Old Town, commemorates the children who served as messengers and frontline troops in the Warsaw Uprising, while the impressive Warsaw Uprising Monument by Wincenty Kućma was erected in memory of the largest insurrection of World War II. The few jews who surived the Warsaw Ghetto uprising of 1943 engaged in the Warsaw uprising together with their Polish-Roman Catholic compatriots.

P.S.- I hope that Bonobo can ad something about Polish-Jewish coexistence, shared battle or conservation of Jewish heritage in Poland. The very little things I know is that there were some mixed Polish-Jewish marriages in my Polish family, in the sense of Roman-Catholic/jewish marriages. The grandmother of a Polish cousin of mine was jewish. But she lived a Roman-Catholic life with her husband.