Post by pjotr on Jul 27, 2019 9:48:42 GMT 1

Dear folks,

Sometimes old news has an interesting insight into the present and shows the newest history to us. This old essay from 2016 is about the weakness of the political left in Poland which isn't represented in the Polish parliament, the Sejm, where not a single progressive, center left or leftwing political party is present reveals some truth from a leftwing Polish intellectual who is critical of the Old Left and in the same time of the New Left in Poland who doesn't manage to gain votes and grow. In the eyes of Sławomir Sierakowski, this comes due to the fact that the present day Polish leftwing parties and movements are still to connected to the 'communist' Old Left ideas and the 'communist' Old Left political class, who were and are dominant in for instance the Post-Communist Social Democratic Democratic Left Alliance (Polish: Sojusz Lewicy Demokratycznej, SLD. This is amazing, because in the formation of the Second Polish Republic (1918–1939) the Polish Socialists played an important role.

Polish Socialists were a typical brand in the Europe of the early 20th century, because they were Polish Patriots and leftwing Nationalists. Their roots lay in the late 19th century. The Polish Socialist Party (Polish: Polska Partia Socjalistyczna, PPS) was a left-wing Polish political party and one of the most important parties in Poland from its inception in 1892 until its dissolution in 1948.

The Polish Socialist Party in 1892 stood for an Independent Republic of Poland based on democratic principles, direct universal voting rights, equal rights for all nations living in Poland, equal rights for all citizens, regardless of race, nationality, religion and gender and freedom of press, speech and assembly. Next to that the PPS stood for Progressive taxation, an Eight-hour workday, a Minimum wage, Equal wages for men and women, a ban on child labour (till age 14), Free education and social support in case of injury in the workplace.

Early in his political career, Józef Piłsudski (5 December 1867 – 12 May 1935) became a leader of the Polish Socialist Party. Concluding that Poland's independence would have to be won militarily, he formed the Polish Legions. In 1914 he correctly predicted that a new major war would defeat the Russian Empire and the Central Powers. When World War I began in 1914, Piłsudski's Legions fought alongside Austria-Hungary against Russia. In 1917, with Imperalist Russia faring poorly in the war, he withdrew his support for the Central Powers and was imprisoned in Magdeburg by the Germans.

Józef Piłsudski was a Polish socialist who became a military leader and Marshal of Poland (Marszałek Polski), the highest rank in the Polish Army.

From November 1918, when Poland regained its independence, until 1922, Piłsudski was Poland's Chief of State. In 1919–21 he commanded Polish forces in six border wars that re-defined the country's borders. On the verge of defeat in the Polish–Soviet War his forces, in the August 1920 Battle of Warsaw, threw back the invading Soviet Russians.

During the Second Polish Republic the PPS at first supported Józef Piłsudski, including his May Coup (in 1926), but later moved into the opposition to his authoritarian Sanacja regime by joining the democratic 'centrolew' (center-left) opposition movement. Many PPS leaders and members were put on trial by Piłsudski's regime and jailed in the infamous Bereza Kartuska prison.

Polish Socialists, Social Democrats and Atheists also played an important role in the anti-communist dissident movements KOR (the Workers' Defense Committee (Polish: Komitet Obrony Robotników) and Solidarność, Polish socialists (leftwing intellectuals) played a role next to conservative Roman Catholics, Liberal Roman Catholics and other Polish Patriots. To name a few Jan Józef Lipski, Adam Michnik, Jacek Kuroń, Karol Modzelewski, Edward Lipiński, Bronisław Geremek and Marek Edelman.

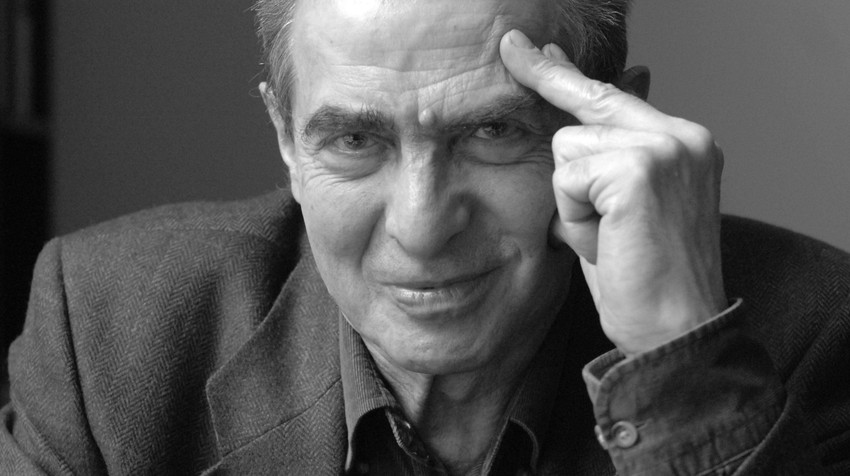

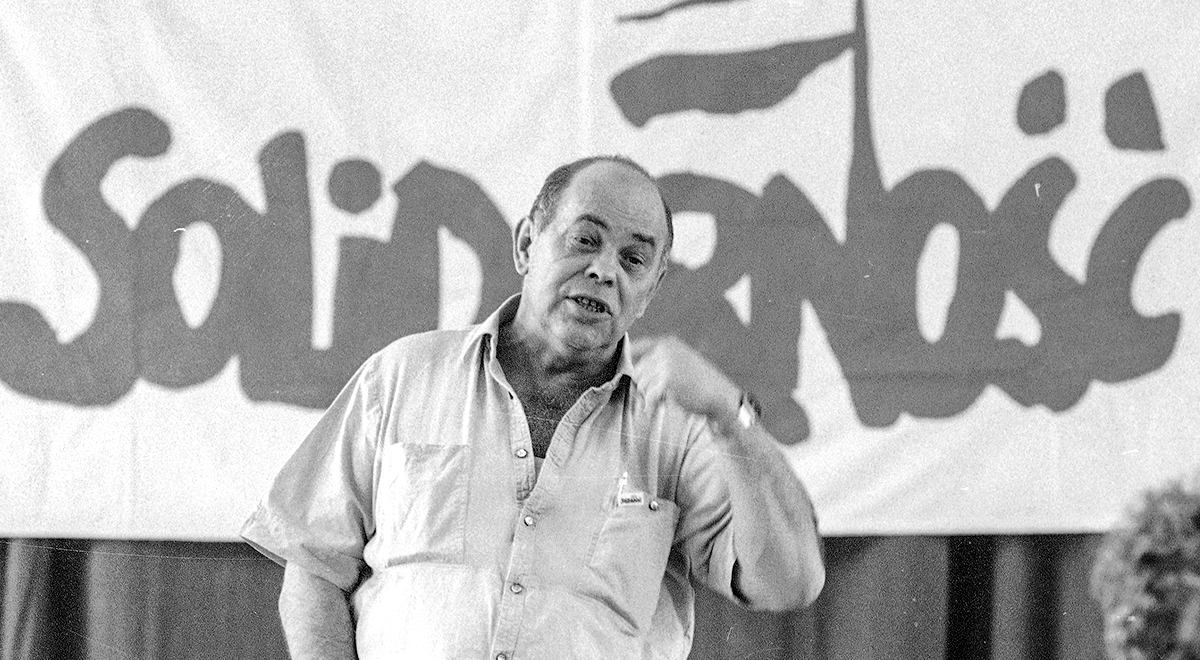

Karol Cyryl Modzelewski

Karol Cyryl Modzelewski (23 November 1937 in Moscow – 28 April 2019) was a Polish historian, writer, politician and academic.

He was the adopted son of Zygmunt Modzelewski. A professor at the University of Wrocław and the University of Warsaw, he was a member of the communist the Polish United Workers Party but was expelled from it in 1964 for opposition to some policies of the party. With Jacek Kuroń he co-wrote the Open Letter to the Party, for which he was imprisoned for three years. He took part in the Polish 1968 political crisis, and for his activities he was again imprisoned for three and a half years.

During the 1980 strikes he came up with the name of 'Solidarity'. He was one of the Solidarity press contacts, and a member of the Solidarity region in Silesia. He was interned with many others during the martial law in Poland. From 1989 to 1991 he was a member of the Polish Senat (Solidarity Citizens' Committee), supporting the left-wing, particularly the Labour Union party and later Włodzimierz Cimoszewicz.

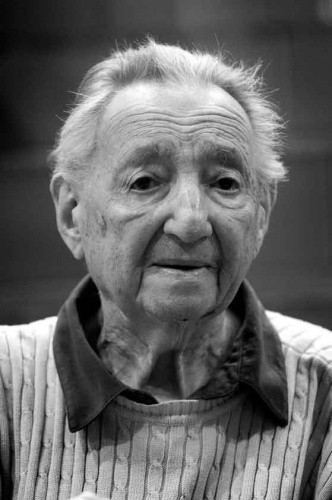

Marek Edelman

After the Second World War Marek Edelman remained in Poland and became a noted cardiologist. From the 1970s, he collaborated with the Workers' Defence Committee and other political groups opposing Poland's communist regime. As a member of Solidarity, he took part in the Polish Round Table Talks of 1989. Following the peaceful transformations of 1989, he was a member of various centrist and liberal parties.

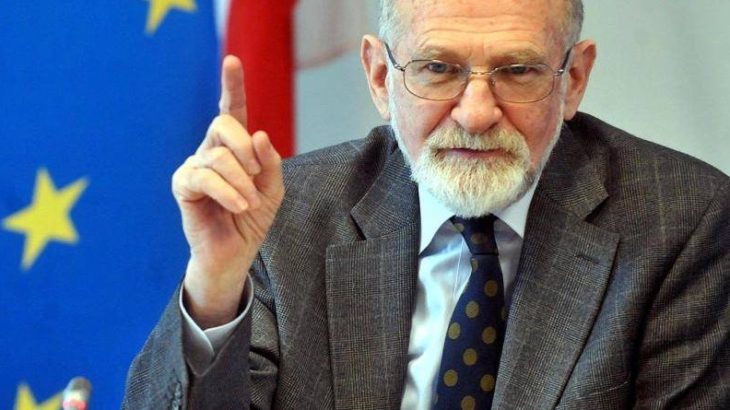

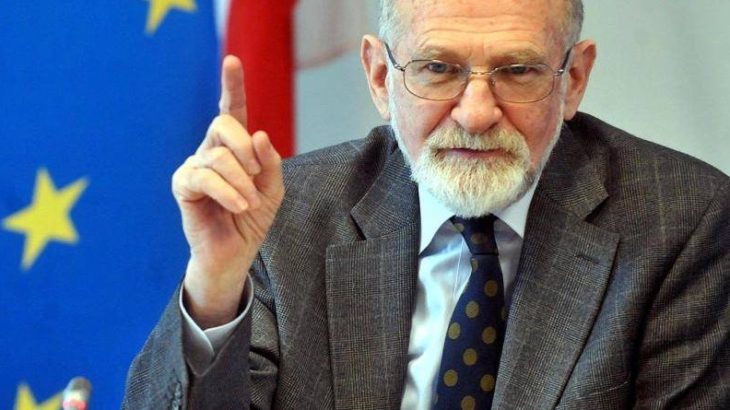

Bronisław Geremek

In the 1970s Bronisław Geremek was considered one of the leading figures in the Polish democratic opposition. In 1978 he co-founded the Society for Educational Courses, for which he gave lectures. While on a Fellowship at the Wilson Center in Washington DC, he met General Edward Rowny who introduced him to Lane Kirkland and Ronald Reagan. In August 1980 he joined the Gdańsk workers' protest movement and became one of the advisers of the Independent Self-Governing Trade Union Solidarność (Polish for "Solidarity") – NSZZ. In 1981 he chaired the Program Commission of the First National Convention of Solidarity. After martial law was declared in December 1981 he was interned until December 1982, when he once again became an adviser to the then-illegal Solidarity, working closely with Lech Wałęsa. In 1983 he was arrested by the Polish authorities.

Between 1987 and 1989 Geremek was the leader of the Commission for Political Reforms of the Civic Committee, which prepared proposals for peaceful democratic transformation in Poland. In 1989 he played a crucial role during the debates between Solidarity and the authorities that led to free parliamentary elections and the establishment of the ‘Contract Sejm’.

Edward Lipiński

Edward Lipiński as a former Socialist (PPS member) and member of the communist PZPR party became one of the prominent critics of the Polish communist government. His position as a known Marxist economist shielded him to certain extent from government persecution and allowed him to say things many others were unable to. Till the very end he remained convinced that some form of socialism is preferable to capitalism. He signed three public letters criticizing the communist government: the Letter of 34 in 1964, the Letter of 59 in 1975 and the Letter of 14 in 1976. In 1977 he was expelled from the PZPR.

Shop queue during PRL – Polska Rzeczpospolita Ludowa (Polish People’s Republic), the official name of Poland between 1952 and 1989. The queue stands in front of a state supermarket, which was called a Sam.

Edward Lipiński

In the spring of 1976, Lipiński sent an open letter to First Secretary Edward Gierek of the PZPR, criticizing the drastic price increase on foodstuffs that Gierek imposed in an attempt to balance Poland's import-based economy that relied heavily on Western loans. Gierek, who came to power after the overthrow of Władysław Gomułka, promised to improve the quality of life of Polish workers by raising wages and stabilizing prices. In his letter Lipiński wrote "Socialism cannot be decreed. It is and may only be born of free actions of free people" and pledged that "the movement of revival shall gain strength and the recently intensified repression will not contain it for much longer…" Lipinski's letter came at the time of renewal of massive strikes and riots in Poland.

The letter also coincided with the formation of the Workers' Defence Committee ( KOR), which marked the beginning of successful cooperation of workers and intellectuals. KOR was founded by Edward Lipiński, Stanisław Barańczak, Jan Józef Lipski and others gave assistance to worker protest participants jailed after the widespread strikes. Lipiński was one of the elder distinguished members of the organization, whose presence added a degree of protection from the authorities. The assistance provided by the KOR and the continual activities of its members helped, after another wave of strikes, make the Gdańsk Agreement of 1980 possible. On 23 September 1981, Lipiński gave a speech to Solidarity independent trade union first national congress, announcing the disbanding of the KOR. He heralded the arrival of Solidarity (Solidarność) as a political force, saying "The KOR has recognized that its work has ended, and that other forces have arrived on a much more powerful scale. But the task of fighting for an independent Poland, for human and civil rights, is a fight that still must go on."

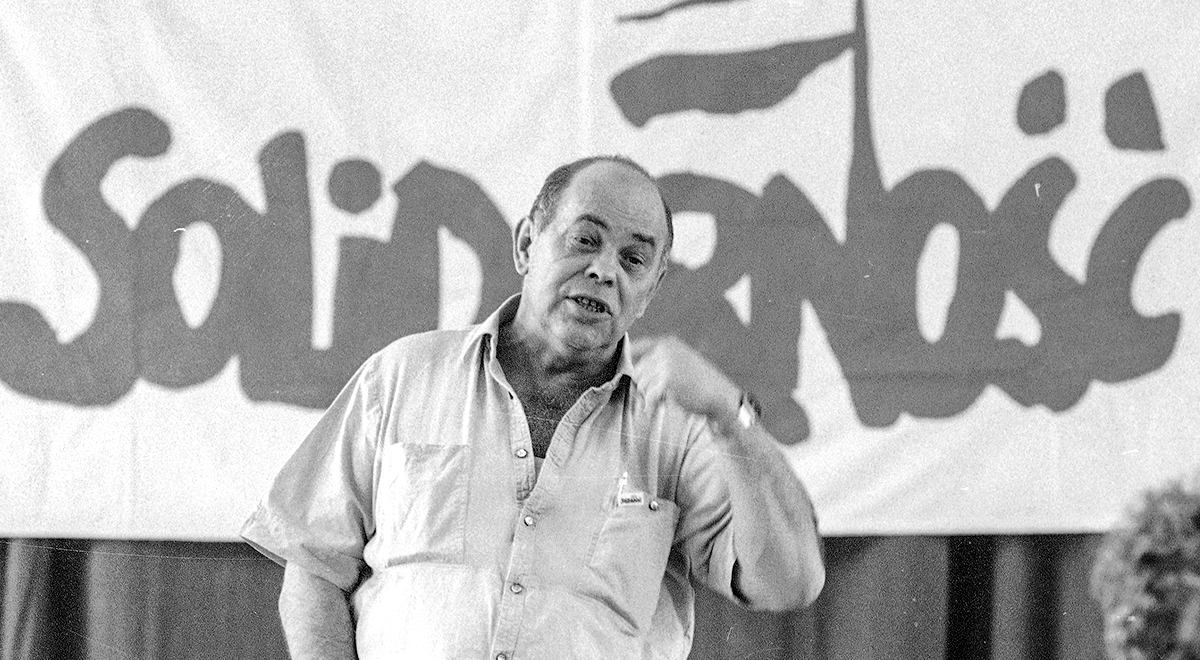

Jacek Kuroń

Jacek Kuroń (1934 – 17 2004) co-founded KOR (The Worker's Defense Committee) with Antoni Macierewicz , a civil organization that helped pave the way for Solidarność (Polish: Solidarity). The Coastal Free Trade Union WZZ, the cradle of Solidarity, was established on April 29, 1978 after Krzysztof Wyszkowski convinced Kuron that workers needed their own voice.

During the strikes of July and August 1980, Kuroń organized an information network for workers across the country. Soon after the Gdansk shipyard occupation began in August 1980, Kuron was imprisoned again, but released with other dissidents, including Adam Michnik, before the signing of the Gdansk agreement of 31 August 1980, conceding the right to form independent unions. In September 1980, he became an adviser for the Founding Committee of the Solidarność. By this time he had changed from the ideas in "An Open Letter to the Party" of revolution and worker's organization taking over society to one of 'self limiting revolution.' On 13 December 1981 the Martial Law was introduced in Poland, and his activities were curtailed. In 1982, accused of attempts to destroy the political system, Kuroń was arrested. Two years later he was pardoned and released from prison.

The leftwing dissident of KOR and Solidarność, Adam Michnik being arrested by the Polish communist Milicja Obywatelska in the Polish Peoples Republic

Adam Michnik (born 17 October 1946) is a Polish historian, essayist, former dissident, public intellectual, and editor-in-chief of the Polish newspaper, Gazeta Wyborcza.

Reared in a family of committed communists, Michnik became an opponent of Poland's communist regime at the time of the party's anti-Jewish purges. He was imprisoned after the 1968 March Events. In 1976–77 he lived in Paris. After he returned to Poland, he became involved in the activity of Workers' Defence Committee (KOR), which had already existed for a couple of months. After the imposition of martial law in 1981 he became imprisoned again.

Michnik played a crucial role during the Polish Round Table Talks, as a result of which the communists agreed to call elections in 1989, which were won by Solidarity. Though he has withdrawn from active politics, he has "maintained an influential voice through journalism". He has received many awards and honors, including the Legion of Honour and European of the Year.

The present day Polish parliament

The Sejm is dominated by centre right, rightwing and far right political parties. The United Right (Polish: Zjednoczona Prawica) the right-wing conservative political alliance in Poland between Law and Justice (Prawo i Sprawiedliwość), United Poland (Solidarna Polska), the Agreement (Porozumienie) and the Republican Party (Partia Republikańska) dominates the Polish parliament with 238 of the in total 460 Sejm seats. The centrist to centre right Civic Coalition(Polish: Koalicja Obywatelska, KO), the electoral alliance in Poland created by the Civic Platform and Modern parties for the 2018 local elections has 155 of the 460 seats in the Sejm.

The Right-wing to far-right Anti-establishment, Right-wing populist, National Conservative, Direct democracy proponent, Soft Eurosceptic and Polish Nationalist Kukiz'15 has 25 seats in the Sejm. The centrist (to centre right) Polish Coalition (Koalicja Polska) political alliance created by Polish People's Party (Polskie Stronnictwo Ludowe), abbreviated to PSL), consists of the Polish People's Party, the Union of European Democrats ((Polish: Unia Europejskich Demokratów, UED), the Alliance of Democrats (Stronnictwo Demokratyczne, SD) and the Labour Party (Stronnictwo Pracy, SP) . The Polish Coalition (Koalicja Polska) has only 22 seats in the Sejm.

Next to this you have the far right and hard Eurosceptic Confederation KORWiN Braun Liroy Nationalists of Janusz Korwin-Mikke and Robert Winnicki, Grzegorz Braun, Piotr Liroy-Marzec,Kaja Godek and Marek Jakubiak. The rightwing Janusz Ryszard Korwin-Mikke is a libertarian conservative who stands for Paleolibertarianism, which means that he combines libertarian anarcho-capitalist ideas of Murray Rothbard and Llewellyn Rockwell with conservative cultural values and a social philosophy with a libertarian opposition to government intervention. Korwin-Mikke believes in the Laissez-faire economic system in which transactions between private parties are free from any form of government intervention such as regulation, privileges, imperialism, tariffs and subsidies.

Korwin-Mikke is a self-declared monarchist and thinks that democracy is the "stupidest form of government ever conceived" where "two bums from under a beer stand have twice as many votes as a university professor". He is a misogynist and his misogynistic views and statements caused outrage in the European parliament and inside Poland, where women opposed his views.

The rightwing National conservative parties and far right Polish nationalist parties are dominant in the Polish parliament and the more centre right Civic Coalition and centrist Polish Coalition are weaker and only have 155 + 22 = 177 seats in the Polish parliament.

The United Left (Polish: Zjednoczona Lewica, ZL) was a political and electoral alliance of political parties in Poland and it received only 7.55 percentof the vote and didn't reach the Polish parliament.

The alliance was formed in July 2015 by the Democratic Left Alliance (Sojusz Lewicy Demokratycznej, SLD), Your Movement (Twój Ruch, TR), the Polish Socialist Party (PPS), Labour United (Unia Pracy UP), and The Greens ( Partia Zieloni, PZ) to jointly contest the forthcoming parliamentary election. The formation of the alliance was in response to the poor performance the Polish centre-left in the 2015 presidential election, and was backed by the All-Poland Alliance of Trade Unions (OPZZ). On 14 September 2015 the Polish Labour Party (Polska Partia Pracy, PPP) joined the alliance. On 4 October 2015, it was announced that Barbara Nowacka, co-leader of TR, would be the alliance's leader and prime ministerial candidate.

Barbara Nowacka, was the leader of The United Left

In the 2015 parliamentary election on 25 October 2015, the United Left (Polish: Zjednoczona Lewica received 7.6% of the vote, below the 8% electoral threshold for electoral alliances (individual parties only need 5%), leaving the alliance without any parliamentary representation. It was dissolved in February 2016.

The Dissenting Voice of Poland’s Intelligentsia

January 27, 2016

This article was originally published (in Dutch) in Groene Amsterdammer on Wednesday 13 January, 2016 (English translation: Daniel Naamani)

With not a single leftist party returned to Polish parliament, the Left must fall back on extra-parliamentary organisation. Sławomir Sierakowski is doing just that with his Krytyka Polityczna. ‘Kaczyński has started a war on liberal democracy.’

by Thijs Kleinpaste

‘The idea of the engaged intelligentsia is a Central-European and an Eastern-European invention; their ethos is very important to me, and we need them more than ever.’ Sławomir Sierakowski, Polish intellectual and activist, is involved with the protests against the dictatorial tendencies of Jarosław Kaczyński’s party Law and Justice (PiS), which gained an absolute majority in the Sejm, Poland’s parliament.

The reactionary Right reigns supreme in Poland. What does it mean to be leftist in such a climate? Sierakowski does not despair. He compares the position of leftist intellectuals and political activists with that of the democratic intelligentsia in nineteenth-century Tsarist Russia.

Warsaw Democracy protests against Law and Justice in 2016. Photo by Marta Modzelewska via Political Critique

Sławomir Sierakowski is a radical political thinker, although his radicalism is mostly thrown into relief by the political stream he is swimming against. He trained as sociologist under Ulrich Beck and was a visiting fellow at American universities like Princeton, Harvard and Yale. He wrote numerous essays and had a column in The New York Times until a year and a half ago. In his homeland Poland he is founder and editor-in-chief of Krytyka Polityczna, a Polish publication of like-minded left-wing intellectuals and activists. The organisation also has cultural centres in Poland and beyond (in the Ukraine, for example), a publishing house that is predominantly devoted to translating (political) treatises from and into Polish, and even community services, such as a crèche.

Ulrich Beck was a well known German sociologist, and one of the most cited social scientists in the world during his lifetime. His work focused on questions of uncontrollability, ignorance and uncertainty in the modern age, and he coined the terms "risk society" and "second modernity" or "reflexive modernization".

Sierakowski’s career was given a big boost following his 2003 initiative to publish an open letter addressed to the general public of Europe, in which he spoke out on behalf of a large group of intellectuals and activists on the European Constitution, which was then being drafted. It was Sierakowski’s view then that his pro-European group wasn’t represented by the conservative Polish government. In a Europe that was moving towards an increasingly tight-knit union, Poland should not be allowed to play the role of an obstructor against further integration, ‘a symbol of conservatism and particularism.’

Thirteen years later, Poland has become precisely that symbol of conservatism. Ever since the Polish government’s attempts to impose restrictions on the independence of public broadcasting and to render the Constitutional Tribunal toothless, Sierakowski has been busier than ever.

As early as October, shortly after PiS’s landslide victory, Sierakowski predicted that Kaczyński would launch an attack on the justice system and the media, but also said that Poland hadn’t quite turned into Hungary yet. The PiS, propelled to prominence by anti-immigration rhetoric, should be seen as a run-of-the-mill extreme right-wing European party: the ‘ironic result of Poland’s integration into the West.’

By now the situation has changed. Kaczyński has done what Sierakowski predicted, but more thoroughly than expected. Sierakowski now writes: ‘Kaczyński has started a war against the liberal democracy. He operates faster than Orbán and Erdoğan. We must organise a united front. The primary battlefield will be mass media and the streets, where for the first time since the end of the Soviet era people are participating in mass demonstrations again. The public broadcaster has been commandeered and in the meantime the government is trying to muzzle the other media too. Kaczyński is squeezing subsidies for organisations that do not conform to his will, starting with Krytyka. It saddens me that this is happening, but I also feel more than ever that I’m in the right place, fighting for my ideas.’

For the first time in post-communist Polish history, not a single left-wing party is represented in parliament. It makes the position of the Left in Poland a thankless one, and that of thinkers like Sierakowski even more so. What to do now? And why are the (extreme) right parties so successful across Europe?

‘There are a number of factors at play,’ says Sierakowski. "There are long-term tendencies such as the disappearance of the differences between mainstream political parties. The differences between parties in the political centre have evaporated. The consequence is that people start looking for a difference, because they want to have something to choose. If they get the impression that there’s nothing to choose, people don’t feel like they’re true citizens. Take the last European elections: why did a quarter of all Europeans vote for a party on the far right? It’s because the establishment parties have already more or less decided on everything before the elections: who will be the European Commissioners, who will supply the President of parliament, and so forth and so on. How does that make people feel, on their way to the polling booth?"

“I would give up a lot to have people like Václav Havel around again today, but he too would lose the elections.”

Then there is also a big crisis on the Left, Sierakowski suggests: ‘Even when left-wing parties do win elections, they are still forced to carry out right-wing policies. Syriza in Greece is the best example of this: a radical left-wing party that has to implement a far-right economic programme. Social-democratic politics have simply become impossible on a national level. People see that, even if they vote left-wing, this still doesn’t result in any left-wing policies, and what is left for them then? Frustrations like these are not easily dispelled/i].’ He cites the ongoing refugee crisis as the third factor: ‘‘Where refugees are taken in, the extreme right’s results double. Europe is extremely rich, but is apparently unwilling to share that wealth.’

Sławomir Sierakowski is without a doubt a political radical, but he’s also a calm radical. His tone is almost neutral, as if he’s simply listing the facts as they are. He doesn’t want to be called a pessimist, he isn’t bitter. His demeanour emanates a calm acceptance of reality by somebody who indeed has ideals, but is otherwise completely free from illusions or false hope.

‘I’m not a pessimist. I’m realistic about the present circumstances and optimistic about the solutions. Of course, you could say that I’m disappointed with the current politics of the Left. That is the reason why I haven’t stayed under the umbrella of party politics. These institutions will continue to exist for a while, but they’re slowly withering away. Party politics is not a synonym for democracy. It was invented in the nineteenth century and can just as well disappear again and make way for something new. Political parties aren’t the rooted organisations they used to be, and we’re now seeing the effect of this in the parties we have left: there is a strong negative selection. We no longer see any real decisive leaders like we had fifty years ago. It’s the “Berlusconisation” of politics. I don’t think it will get better.’

In response to the argument that parliamentary politics has always had a close relationship with party politics, Sierakowski says that his goal isn’t to reject democracy itself. ‘I’m wary of upsetting the fragile system of democracy. Nobody has ever come up with anything better, but we have seen a lot of worse things. What I propose is that we perhaps need to look for party politics on a higher level, but that seems impossible in these circumstances. We are being dominated by the crappy culture of narcissism propagated by little nations, including Poland. This culture is given new impetus by political parties that are playing the ‘national culture’ card as a way of solving things. The problems of nation states are brought on by their own inefficiency, and nationalist parties promise to solve them by appealing to the idea of national pride or purity, with no refugees or ‘other people’. This is our dilemma. People have stopped believing that things can change. Politics has turned cynical and this made society cynical too, so we shouldn’t be surprised that people are behaving selfishly. I would give up a lot to have people like Václav Havel around again today, but he too would flat out lose the elections in this day and age.’

Václav Havel is still popular under leftwing intelligentsia this day, but they realise that probably even Václav Havel would not have been voted for today if he participated in the Czech elections, because we live in different times.

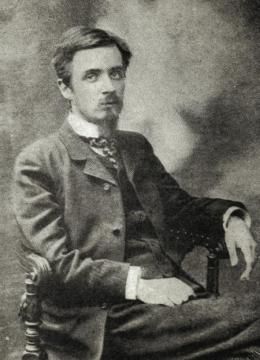

Middle-class philosophies are in crisis, says Sierakowski, and that’s why an alternative strategy is essential. In order to find pegs to hang that strategy on, he looks back to the past, among other things to the life and work of Polish literary critic Stanisław Brzozowski. Krytyka and Sierakowski derive their political ethos from this Polish intellectual. Brzozowski (1878-1911) was a Marxist literary critic, writer and essayist. He died at the age of 33 of tuberculosis, but had by that time already written several books and hundreds of essays. Nearly every Polish thinker of any consequence has written about him. Leszek Kołakowski discussed Brzozowski extensively in his substantial History of Marxism; Czesław Miłosz was his literary biographer. Historian Andrzej Walicki described his vision as deeply-ingrained individualism, and a Promethean Marxism which puts mankind at the centre instead of materialistic dialectics.

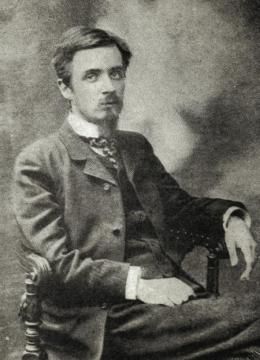

Polish Marxist literary critic, writer and essayist Stanisław Brzozowski (1878-1911).

Brzozowski was a fundamentally eclectic thinker and placed great emphasis (as did the great Russian thinkers of the nineteenth century before him) on the duty of the intelligentsia to push for the liberation and elevation of the working class. Fifteen years ago, Krytyka started out with a seething j’accuse that denounced the tired and quotidian political culture of Poland. Its title: ‘Intelligentsia: helpless or dead?’

Brzozowski belonged to the Eastern-European intelligentsia that hoped to carry out the task they set themselves, to go to the people. Sierakowski: ‘He was an exceptionally engaged person. He worked himself to the bone, as a writer, as an intellectual and as an activist. He was a fascinating individual. Somebody once described his work as “philosophical vodka”, but his philosophy is deeply humanist. All Polish dissidents during communism, including Miłosz, were influenced by him.’

Brzozowski’s influence can also be felt today. ‘It’s the intelligentsia’s duty’, says Sierakowski, ‘to once more “go back to the people”, as it was called in the nineteenth century. We are living in an atomised world, so what do we need? Binding agent. If people are to get back to solving problems together, there needs to be commitment.’

Krytyka is part of a long Eastern-European tradition, Sierakowski continues, which Western Europeans don’t always find easy to comprehend. ‘The word “intelligentsia” originated here in Eastern Europe, in the mid-nineteenth century. The existence of the intelligentsia is a symptom of backwardness. These people wanted to compensate for the lack of strong institutions, institutions that the West did have: cities, universities, state-run institutions. In Poland’s case, there wasn’t even a state. So if people wanted an enlightened society, or if they wanted to stand up for labourers or women’s rights, it was essential to have a group of dedicated people who were willing to devote their existence to the realisation of their ideals – a classic job for the intelligentsia.’

“The goal of the intelligentsia should be a kind of successful suicide, that is to say: to eventually become obsolete”

With not a single leftist party represented in the Polish parliament, there is a need to fall back on alternative, extra-parliamentary organisation. ‘The Left in Poland is in difficulty because their body of ideas is still based on post-communism, which is essentially a reincarnation of the old idea — more democratic, and generally better than under the former communist regime, but still outmoded and not “left” in the modern sense of the word. Who joined the communist party in the nineteen-eighties? They weren’t left-wing people, their motivation was different: power and status, influence.’

Like most countries from the original Soviet bloc, Poland was extremely illiberal, Sierakowski contends, a direct result of the communist era. ‘Communism functioned as a deep freeze. People awoke at the beginning of the nineties without having experienced the slightest influence of feminism or the gay movement, so even a lot of the left-wing dissidents were still quite conservative socially speaking. To let new ideas catch on, you need to organise people, engage in conversation with them, and persist. First they’ll laugh at you. Then they’ll laugh at you again. Then they’ll still be laughing at you. But in the end, if you survive and are still standing, after considerable time you will be able to convince people.’

This emphasis on constant organisation – a process that takes place completely outside of the parliamentary context – is fundamental for the task Sierakowski sees for Krytyka: ‘If you work with people for years on end, especially outside of the big cities, you have to be committed. It eats up a lot of energy, but in the end you will succeed because you have been able to create common experiences. The first job at hand is to form a powerful committed citizenship. The higher levels can reform the basis, later Marxists were right when they identified the public discourse as an important tool to change society.’

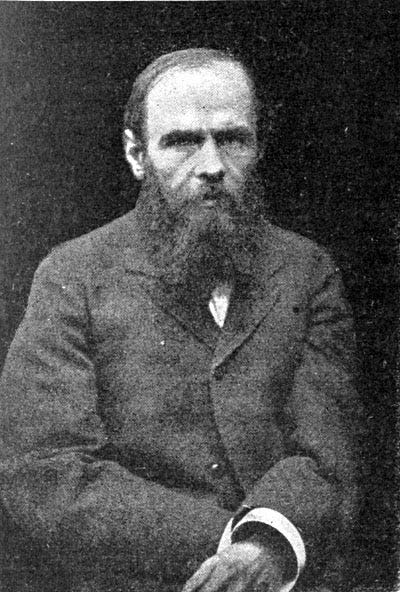

Bearing Brzozowski in mind, Sierakowski believes that this job is one pre-eminently suited to artists, musicians and writers. It is the duty of the intellectual and writer, Brzozowski thought, to speak out for a better society, to stand up for individualism. From an early age onwards, Brzozowski was fascinated by Russian nineteenth-century literature and the ideas that were dicussed by writers like Dostoyevsky. In response to the latter’s novel Demons, Brzozowski wrote his own novel, Flames, in which he challenged Dostoyevsky’s gloomy worldview and launched an attack on the remains of feudal conservatism, tradition, clericalism and capitalism.

But what if Dostoyevsky’s ultimate vision about mankind were closer to the truth than the individualistic or humanistic left-wing ideal? What if people, after having laughed a fourth time at the activists who “go to the people”, keep laughing? What if they don’t want to be free in the way that others have in mind for them?

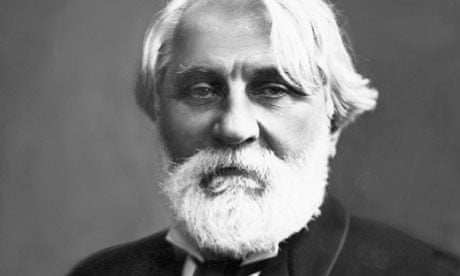

‘I consider Dostoyevsky as the most important challenger of left-wingers anywhere’, replies Sierakowski. ‘If you think you are left-wing, of if you want to be left-wing, you have to be willing to hold your ideas up to Dostoyevsky. He is a test. Look at Notes from Underground, and look at the bigger discussion that book was part of, between Chernyshevsky (with What Is to Be Done), Turgenev (Fathers and Sons) and Dostoyevsky himself.’

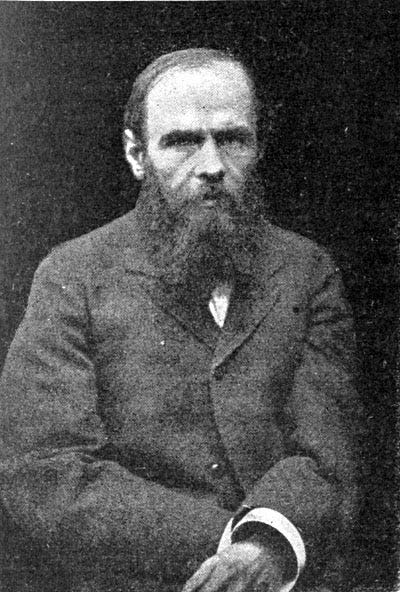

Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky (11 November 1821 – 9 February 1881), sometimes transliterated Dostoyevsky, was a Russian novelist, short story writer, essayist, journalist and philosopher. Dostoevsky's literary works explore human psychology in the troubled political, social, and spiritual atmospheres of 19th-century Russia, and engage with a variety of philosophical and religious themes.

The discussion that plays in the background in the works of Dostoyevsky and Turgenev was sparked by Chernyshevsky, who had sketched a rationalist utopia in What Is to Be Done, to benefit the Russian rural proletariat. Turgenev called his views nihilism and Dostoyevsky, for his part, struck back with the Underground Man. No matter how beautiful and salutary, how sensible the utopia is made out to be, the underground man doesn’t care for it – the only thing he holds on to with all his might is his autonomy, which is worth more to him than any plan or programme could ever be. That the price for his autonomy is great unhappiness doesn’t bother him; at least it’s his unhappiness. ‘In his Notes from Underground Dostoyevsky essentially argued that rational utopia probably doesn’t bring freedom. For myself the lesson is also that one should, ultimately, believe. When it comes down to it, you can’t let your ideas rest on some scientific groundwork. This also means, by the way, that you always have to be a bit suspicious of yourself.’

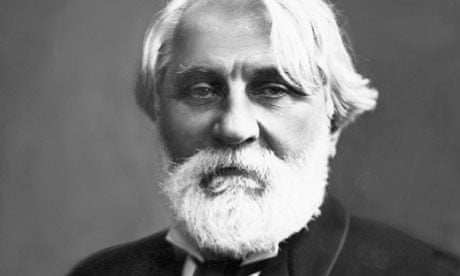

Ivan Sergeyevich Turgenev (October 28] 1818 – September 3, 1883) was a Russian novelist, short story writer, poet, playwright, translator and popularizer of Russian literature in the West.

Nikolay Gavrilovich Chernyshevsky (12 July 1828 – 17 October 1889) was a Russian revolutionary democrat, materialist philosopher, editor, critic, and socialist (seen by some as a utopian socialist). He was the leader of the revolutionary democratic movement of the 1860s, and had an influence on Vladimir Lenin, Emma Goldman, and Serbian political writer and socialist Svetozar Marković.

Turgenev belonged to the superfluous generation. The generation that did have some abstract ideals, but that ran up against the tyranny of Tsarist Russia. Sierakowski: ‘Today’s intelligentsia feels the same way. We are the superfluous people Turgenev wrote about. The goal of the intelligentsia should be a kind of successful suicide, that is to say: to eventually become obsolete, because society can solve its own social problems.’

The main thing is, in a word, dedication. Sierakowski quotes Brzozowski one last time. ‘He wrote: “What is not biography, is nothing.” This means that ideals are realised by living them. Through patience, mistakes, persistence and repetition. It’s the idea that you can’t fall back on abstract ideas without taking reality into account. You have to be sceptical. Whenever you try to implement abstractions – whatever they are: socialism, feminism – it always creates problems, and sometimes atrocities. Only shared experiences, political experiences, can cause people to change. Those who want to save politics should counter atomisation, and this means that connections between people need to be cultivated. That is the most effective antidote against distrust and cynicism – and we know: those two things are the main obstacles to reclaiming democracy.’

Further reading:

The Polish Threat to Europe by Sławomir Sierakowski (published on 19 January 2016 in Project Syndicate)

Sierakowski: No Freedom Without Solidarity! [Interview] (published on 22 January on Political Critique's website)

Krytyka Polityczna is one of the six hubs in ECF's Connected Action for the Commons programme.

Sometimes old news has an interesting insight into the present and shows the newest history to us. This old essay from 2016 is about the weakness of the political left in Poland which isn't represented in the Polish parliament, the Sejm, where not a single progressive, center left or leftwing political party is present reveals some truth from a leftwing Polish intellectual who is critical of the Old Left and in the same time of the New Left in Poland who doesn't manage to gain votes and grow. In the eyes of Sławomir Sierakowski, this comes due to the fact that the present day Polish leftwing parties and movements are still to connected to the 'communist' Old Left ideas and the 'communist' Old Left political class, who were and are dominant in for instance the Post-Communist Social Democratic Democratic Left Alliance (Polish: Sojusz Lewicy Demokratycznej, SLD. This is amazing, because in the formation of the Second Polish Republic (1918–1939) the Polish Socialists played an important role.

Polish Socialists were a typical brand in the Europe of the early 20th century, because they were Polish Patriots and leftwing Nationalists. Their roots lay in the late 19th century. The Polish Socialist Party (Polish: Polska Partia Socjalistyczna, PPS) was a left-wing Polish political party and one of the most important parties in Poland from its inception in 1892 until its dissolution in 1948.

The Polish Socialist Party in 1892 stood for an Independent Republic of Poland based on democratic principles, direct universal voting rights, equal rights for all nations living in Poland, equal rights for all citizens, regardless of race, nationality, religion and gender and freedom of press, speech and assembly. Next to that the PPS stood for Progressive taxation, an Eight-hour workday, a Minimum wage, Equal wages for men and women, a ban on child labour (till age 14), Free education and social support in case of injury in the workplace.

Early in his political career, Józef Piłsudski (5 December 1867 – 12 May 1935) became a leader of the Polish Socialist Party. Concluding that Poland's independence would have to be won militarily, he formed the Polish Legions. In 1914 he correctly predicted that a new major war would defeat the Russian Empire and the Central Powers. When World War I began in 1914, Piłsudski's Legions fought alongside Austria-Hungary against Russia. In 1917, with Imperalist Russia faring poorly in the war, he withdrew his support for the Central Powers and was imprisoned in Magdeburg by the Germans.

Józef Piłsudski was a Polish socialist who became a military leader and Marshal of Poland (Marszałek Polski), the highest rank in the Polish Army.

From November 1918, when Poland regained its independence, until 1922, Piłsudski was Poland's Chief of State. In 1919–21 he commanded Polish forces in six border wars that re-defined the country's borders. On the verge of defeat in the Polish–Soviet War his forces, in the August 1920 Battle of Warsaw, threw back the invading Soviet Russians.

During the Second Polish Republic the PPS at first supported Józef Piłsudski, including his May Coup (in 1926), but later moved into the opposition to his authoritarian Sanacja regime by joining the democratic 'centrolew' (center-left) opposition movement. Many PPS leaders and members were put on trial by Piłsudski's regime and jailed in the infamous Bereza Kartuska prison.

Polish Socialists, Social Democrats and Atheists also played an important role in the anti-communist dissident movements KOR (the Workers' Defense Committee (Polish: Komitet Obrony Robotników) and Solidarność, Polish socialists (leftwing intellectuals) played a role next to conservative Roman Catholics, Liberal Roman Catholics and other Polish Patriots. To name a few Jan Józef Lipski, Adam Michnik, Jacek Kuroń, Karol Modzelewski, Edward Lipiński, Bronisław Geremek and Marek Edelman.

Karol Cyryl Modzelewski

Karol Cyryl Modzelewski (23 November 1937 in Moscow – 28 April 2019) was a Polish historian, writer, politician and academic.

He was the adopted son of Zygmunt Modzelewski. A professor at the University of Wrocław and the University of Warsaw, he was a member of the communist the Polish United Workers Party but was expelled from it in 1964 for opposition to some policies of the party. With Jacek Kuroń he co-wrote the Open Letter to the Party, for which he was imprisoned for three years. He took part in the Polish 1968 political crisis, and for his activities he was again imprisoned for three and a half years.

During the 1980 strikes he came up with the name of 'Solidarity'. He was one of the Solidarity press contacts, and a member of the Solidarity region in Silesia. He was interned with many others during the martial law in Poland. From 1989 to 1991 he was a member of the Polish Senat (Solidarity Citizens' Committee), supporting the left-wing, particularly the Labour Union party and later Włodzimierz Cimoszewicz.

Marek Edelman

After the Second World War Marek Edelman remained in Poland and became a noted cardiologist. From the 1970s, he collaborated with the Workers' Defence Committee and other political groups opposing Poland's communist regime. As a member of Solidarity, he took part in the Polish Round Table Talks of 1989. Following the peaceful transformations of 1989, he was a member of various centrist and liberal parties.

Bronisław Geremek

In the 1970s Bronisław Geremek was considered one of the leading figures in the Polish democratic opposition. In 1978 he co-founded the Society for Educational Courses, for which he gave lectures. While on a Fellowship at the Wilson Center in Washington DC, he met General Edward Rowny who introduced him to Lane Kirkland and Ronald Reagan. In August 1980 he joined the Gdańsk workers' protest movement and became one of the advisers of the Independent Self-Governing Trade Union Solidarność (Polish for "Solidarity") – NSZZ. In 1981 he chaired the Program Commission of the First National Convention of Solidarity. After martial law was declared in December 1981 he was interned until December 1982, when he once again became an adviser to the then-illegal Solidarity, working closely with Lech Wałęsa. In 1983 he was arrested by the Polish authorities.

Between 1987 and 1989 Geremek was the leader of the Commission for Political Reforms of the Civic Committee, which prepared proposals for peaceful democratic transformation in Poland. In 1989 he played a crucial role during the debates between Solidarity and the authorities that led to free parliamentary elections and the establishment of the ‘Contract Sejm’.

Edward Lipiński

Edward Lipiński as a former Socialist (PPS member) and member of the communist PZPR party became one of the prominent critics of the Polish communist government. His position as a known Marxist economist shielded him to certain extent from government persecution and allowed him to say things many others were unable to. Till the very end he remained convinced that some form of socialism is preferable to capitalism. He signed three public letters criticizing the communist government: the Letter of 34 in 1964, the Letter of 59 in 1975 and the Letter of 14 in 1976. In 1977 he was expelled from the PZPR.

Shop queue during PRL – Polska Rzeczpospolita Ludowa (Polish People’s Republic), the official name of Poland between 1952 and 1989. The queue stands in front of a state supermarket, which was called a Sam.

Edward Lipiński

In the spring of 1976, Lipiński sent an open letter to First Secretary Edward Gierek of the PZPR, criticizing the drastic price increase on foodstuffs that Gierek imposed in an attempt to balance Poland's import-based economy that relied heavily on Western loans. Gierek, who came to power after the overthrow of Władysław Gomułka, promised to improve the quality of life of Polish workers by raising wages and stabilizing prices. In his letter Lipiński wrote "Socialism cannot be decreed. It is and may only be born of free actions of free people" and pledged that "the movement of revival shall gain strength and the recently intensified repression will not contain it for much longer…" Lipinski's letter came at the time of renewal of massive strikes and riots in Poland.

The letter also coincided with the formation of the Workers' Defence Committee ( KOR), which marked the beginning of successful cooperation of workers and intellectuals. KOR was founded by Edward Lipiński, Stanisław Barańczak, Jan Józef Lipski and others gave assistance to worker protest participants jailed after the widespread strikes. Lipiński was one of the elder distinguished members of the organization, whose presence added a degree of protection from the authorities. The assistance provided by the KOR and the continual activities of its members helped, after another wave of strikes, make the Gdańsk Agreement of 1980 possible. On 23 September 1981, Lipiński gave a speech to Solidarity independent trade union first national congress, announcing the disbanding of the KOR. He heralded the arrival of Solidarity (Solidarność) as a political force, saying "The KOR has recognized that its work has ended, and that other forces have arrived on a much more powerful scale. But the task of fighting for an independent Poland, for human and civil rights, is a fight that still must go on."

Jacek Kuroń

Jacek Kuroń (1934 – 17 2004) co-founded KOR (The Worker's Defense Committee) with Antoni Macierewicz , a civil organization that helped pave the way for Solidarność (Polish: Solidarity). The Coastal Free Trade Union WZZ, the cradle of Solidarity, was established on April 29, 1978 after Krzysztof Wyszkowski convinced Kuron that workers needed their own voice.

During the strikes of July and August 1980, Kuroń organized an information network for workers across the country. Soon after the Gdansk shipyard occupation began in August 1980, Kuron was imprisoned again, but released with other dissidents, including Adam Michnik, before the signing of the Gdansk agreement of 31 August 1980, conceding the right to form independent unions. In September 1980, he became an adviser for the Founding Committee of the Solidarność. By this time he had changed from the ideas in "An Open Letter to the Party" of revolution and worker's organization taking over society to one of 'self limiting revolution.' On 13 December 1981 the Martial Law was introduced in Poland, and his activities were curtailed. In 1982, accused of attempts to destroy the political system, Kuroń was arrested. Two years later he was pardoned and released from prison.

The leftwing dissident of KOR and Solidarność, Adam Michnik being arrested by the Polish communist Milicja Obywatelska in the Polish Peoples Republic

Adam Michnik (born 17 October 1946) is a Polish historian, essayist, former dissident, public intellectual, and editor-in-chief of the Polish newspaper, Gazeta Wyborcza.

Reared in a family of committed communists, Michnik became an opponent of Poland's communist regime at the time of the party's anti-Jewish purges. He was imprisoned after the 1968 March Events. In 1976–77 he lived in Paris. After he returned to Poland, he became involved in the activity of Workers' Defence Committee (KOR), which had already existed for a couple of months. After the imposition of martial law in 1981 he became imprisoned again.

Michnik played a crucial role during the Polish Round Table Talks, as a result of which the communists agreed to call elections in 1989, which were won by Solidarity. Though he has withdrawn from active politics, he has "maintained an influential voice through journalism". He has received many awards and honors, including the Legion of Honour and European of the Year.

The present day Polish parliament

The Sejm is dominated by centre right, rightwing and far right political parties. The United Right (Polish: Zjednoczona Prawica) the right-wing conservative political alliance in Poland between Law and Justice (Prawo i Sprawiedliwość), United Poland (Solidarna Polska), the Agreement (Porozumienie) and the Republican Party (Partia Republikańska) dominates the Polish parliament with 238 of the in total 460 Sejm seats. The centrist to centre right Civic Coalition(Polish: Koalicja Obywatelska, KO), the electoral alliance in Poland created by the Civic Platform and Modern parties for the 2018 local elections has 155 of the 460 seats in the Sejm.

The Right-wing to far-right Anti-establishment, Right-wing populist, National Conservative, Direct democracy proponent, Soft Eurosceptic and Polish Nationalist Kukiz'15 has 25 seats in the Sejm. The centrist (to centre right) Polish Coalition (Koalicja Polska) political alliance created by Polish People's Party (Polskie Stronnictwo Ludowe), abbreviated to PSL), consists of the Polish People's Party, the Union of European Democrats ((Polish: Unia Europejskich Demokratów, UED), the Alliance of Democrats (Stronnictwo Demokratyczne, SD) and the Labour Party (Stronnictwo Pracy, SP) . The Polish Coalition (Koalicja Polska) has only 22 seats in the Sejm.

Next to this you have the far right and hard Eurosceptic Confederation KORWiN Braun Liroy Nationalists of Janusz Korwin-Mikke and Robert Winnicki, Grzegorz Braun, Piotr Liroy-Marzec,Kaja Godek and Marek Jakubiak. The rightwing Janusz Ryszard Korwin-Mikke is a libertarian conservative who stands for Paleolibertarianism, which means that he combines libertarian anarcho-capitalist ideas of Murray Rothbard and Llewellyn Rockwell with conservative cultural values and a social philosophy with a libertarian opposition to government intervention. Korwin-Mikke believes in the Laissez-faire economic system in which transactions between private parties are free from any form of government intervention such as regulation, privileges, imperialism, tariffs and subsidies.

Korwin-Mikke is a self-declared monarchist and thinks that democracy is the "stupidest form of government ever conceived" where "two bums from under a beer stand have twice as many votes as a university professor". He is a misogynist and his misogynistic views and statements caused outrage in the European parliament and inside Poland, where women opposed his views.

The rightwing National conservative parties and far right Polish nationalist parties are dominant in the Polish parliament and the more centre right Civic Coalition and centrist Polish Coalition are weaker and only have 155 + 22 = 177 seats in the Polish parliament.

The United Left (Polish: Zjednoczona Lewica, ZL) was a political and electoral alliance of political parties in Poland and it received only 7.55 percentof the vote and didn't reach the Polish parliament.

The alliance was formed in July 2015 by the Democratic Left Alliance (Sojusz Lewicy Demokratycznej, SLD), Your Movement (Twój Ruch, TR), the Polish Socialist Party (PPS), Labour United (Unia Pracy UP), and The Greens ( Partia Zieloni, PZ) to jointly contest the forthcoming parliamentary election. The formation of the alliance was in response to the poor performance the Polish centre-left in the 2015 presidential election, and was backed by the All-Poland Alliance of Trade Unions (OPZZ). On 14 September 2015 the Polish Labour Party (Polska Partia Pracy, PPP) joined the alliance. On 4 October 2015, it was announced that Barbara Nowacka, co-leader of TR, would be the alliance's leader and prime ministerial candidate.

Barbara Nowacka, was the leader of The United Left

In the 2015 parliamentary election on 25 October 2015, the United Left (Polish: Zjednoczona Lewica received 7.6% of the vote, below the 8% electoral threshold for electoral alliances (individual parties only need 5%), leaving the alliance without any parliamentary representation. It was dissolved in February 2016.

The Dissenting Voice of Poland’s Intelligentsia

January 27, 2016

This article was originally published (in Dutch) in Groene Amsterdammer on Wednesday 13 January, 2016 (English translation: Daniel Naamani)

With not a single leftist party returned to Polish parliament, the Left must fall back on extra-parliamentary organisation. Sławomir Sierakowski is doing just that with his Krytyka Polityczna. ‘Kaczyński has started a war on liberal democracy.’

by Thijs Kleinpaste

‘The idea of the engaged intelligentsia is a Central-European and an Eastern-European invention; their ethos is very important to me, and we need them more than ever.’ Sławomir Sierakowski, Polish intellectual and activist, is involved with the protests against the dictatorial tendencies of Jarosław Kaczyński’s party Law and Justice (PiS), which gained an absolute majority in the Sejm, Poland’s parliament.

The reactionary Right reigns supreme in Poland. What does it mean to be leftist in such a climate? Sierakowski does not despair. He compares the position of leftist intellectuals and political activists with that of the democratic intelligentsia in nineteenth-century Tsarist Russia.

Warsaw Democracy protests against Law and Justice in 2016. Photo by Marta Modzelewska via Political Critique

Sławomir Sierakowski is a radical political thinker, although his radicalism is mostly thrown into relief by the political stream he is swimming against. He trained as sociologist under Ulrich Beck and was a visiting fellow at American universities like Princeton, Harvard and Yale. He wrote numerous essays and had a column in The New York Times until a year and a half ago. In his homeland Poland he is founder and editor-in-chief of Krytyka Polityczna, a Polish publication of like-minded left-wing intellectuals and activists. The organisation also has cultural centres in Poland and beyond (in the Ukraine, for example), a publishing house that is predominantly devoted to translating (political) treatises from and into Polish, and even community services, such as a crèche.

Ulrich Beck was a well known German sociologist, and one of the most cited social scientists in the world during his lifetime. His work focused on questions of uncontrollability, ignorance and uncertainty in the modern age, and he coined the terms "risk society" and "second modernity" or "reflexive modernization".

Sierakowski’s career was given a big boost following his 2003 initiative to publish an open letter addressed to the general public of Europe, in which he spoke out on behalf of a large group of intellectuals and activists on the European Constitution, which was then being drafted. It was Sierakowski’s view then that his pro-European group wasn’t represented by the conservative Polish government. In a Europe that was moving towards an increasingly tight-knit union, Poland should not be allowed to play the role of an obstructor against further integration, ‘a symbol of conservatism and particularism.’

Thirteen years later, Poland has become precisely that symbol of conservatism. Ever since the Polish government’s attempts to impose restrictions on the independence of public broadcasting and to render the Constitutional Tribunal toothless, Sierakowski has been busier than ever.

As early as October, shortly after PiS’s landslide victory, Sierakowski predicted that Kaczyński would launch an attack on the justice system and the media, but also said that Poland hadn’t quite turned into Hungary yet. The PiS, propelled to prominence by anti-immigration rhetoric, should be seen as a run-of-the-mill extreme right-wing European party: the ‘ironic result of Poland’s integration into the West.’

By now the situation has changed. Kaczyński has done what Sierakowski predicted, but more thoroughly than expected. Sierakowski now writes: ‘Kaczyński has started a war against the liberal democracy. He operates faster than Orbán and Erdoğan. We must organise a united front. The primary battlefield will be mass media and the streets, where for the first time since the end of the Soviet era people are participating in mass demonstrations again. The public broadcaster has been commandeered and in the meantime the government is trying to muzzle the other media too. Kaczyński is squeezing subsidies for organisations that do not conform to his will, starting with Krytyka. It saddens me that this is happening, but I also feel more than ever that I’m in the right place, fighting for my ideas.’

For the first time in post-communist Polish history, not a single left-wing party is represented in parliament. It makes the position of the Left in Poland a thankless one, and that of thinkers like Sierakowski even more so. What to do now? And why are the (extreme) right parties so successful across Europe?

‘There are a number of factors at play,’ says Sierakowski. "There are long-term tendencies such as the disappearance of the differences between mainstream political parties. The differences between parties in the political centre have evaporated. The consequence is that people start looking for a difference, because they want to have something to choose. If they get the impression that there’s nothing to choose, people don’t feel like they’re true citizens. Take the last European elections: why did a quarter of all Europeans vote for a party on the far right? It’s because the establishment parties have already more or less decided on everything before the elections: who will be the European Commissioners, who will supply the President of parliament, and so forth and so on. How does that make people feel, on their way to the polling booth?"

“I would give up a lot to have people like Václav Havel around again today, but he too would lose the elections.”

Then there is also a big crisis on the Left, Sierakowski suggests: ‘Even when left-wing parties do win elections, they are still forced to carry out right-wing policies. Syriza in Greece is the best example of this: a radical left-wing party that has to implement a far-right economic programme. Social-democratic politics have simply become impossible on a national level. People see that, even if they vote left-wing, this still doesn’t result in any left-wing policies, and what is left for them then? Frustrations like these are not easily dispelled/i].’ He cites the ongoing refugee crisis as the third factor: ‘‘Where refugees are taken in, the extreme right’s results double. Europe is extremely rich, but is apparently unwilling to share that wealth.’

Sławomir Sierakowski is without a doubt a political radical, but he’s also a calm radical. His tone is almost neutral, as if he’s simply listing the facts as they are. He doesn’t want to be called a pessimist, he isn’t bitter. His demeanour emanates a calm acceptance of reality by somebody who indeed has ideals, but is otherwise completely free from illusions or false hope.

‘I’m not a pessimist. I’m realistic about the present circumstances and optimistic about the solutions. Of course, you could say that I’m disappointed with the current politics of the Left. That is the reason why I haven’t stayed under the umbrella of party politics. These institutions will continue to exist for a while, but they’re slowly withering away. Party politics is not a synonym for democracy. It was invented in the nineteenth century and can just as well disappear again and make way for something new. Political parties aren’t the rooted organisations they used to be, and we’re now seeing the effect of this in the parties we have left: there is a strong negative selection. We no longer see any real decisive leaders like we had fifty years ago. It’s the “Berlusconisation” of politics. I don’t think it will get better.’

In response to the argument that parliamentary politics has always had a close relationship with party politics, Sierakowski says that his goal isn’t to reject democracy itself. ‘I’m wary of upsetting the fragile system of democracy. Nobody has ever come up with anything better, but we have seen a lot of worse things. What I propose is that we perhaps need to look for party politics on a higher level, but that seems impossible in these circumstances. We are being dominated by the crappy culture of narcissism propagated by little nations, including Poland. This culture is given new impetus by political parties that are playing the ‘national culture’ card as a way of solving things. The problems of nation states are brought on by their own inefficiency, and nationalist parties promise to solve them by appealing to the idea of national pride or purity, with no refugees or ‘other people’. This is our dilemma. People have stopped believing that things can change. Politics has turned cynical and this made society cynical too, so we shouldn’t be surprised that people are behaving selfishly. I would give up a lot to have people like Václav Havel around again today, but he too would flat out lose the elections in this day and age.’

Václav Havel is still popular under leftwing intelligentsia this day, but they realise that probably even Václav Havel would not have been voted for today if he participated in the Czech elections, because we live in different times.

Middle-class philosophies are in crisis, says Sierakowski, and that’s why an alternative strategy is essential. In order to find pegs to hang that strategy on, he looks back to the past, among other things to the life and work of Polish literary critic Stanisław Brzozowski. Krytyka and Sierakowski derive their political ethos from this Polish intellectual. Brzozowski (1878-1911) was a Marxist literary critic, writer and essayist. He died at the age of 33 of tuberculosis, but had by that time already written several books and hundreds of essays. Nearly every Polish thinker of any consequence has written about him. Leszek Kołakowski discussed Brzozowski extensively in his substantial History of Marxism; Czesław Miłosz was his literary biographer. Historian Andrzej Walicki described his vision as deeply-ingrained individualism, and a Promethean Marxism which puts mankind at the centre instead of materialistic dialectics.

Polish Marxist literary critic, writer and essayist Stanisław Brzozowski (1878-1911).

Brzozowski was a fundamentally eclectic thinker and placed great emphasis (as did the great Russian thinkers of the nineteenth century before him) on the duty of the intelligentsia to push for the liberation and elevation of the working class. Fifteen years ago, Krytyka started out with a seething j’accuse that denounced the tired and quotidian political culture of Poland. Its title: ‘Intelligentsia: helpless or dead?’

Brzozowski belonged to the Eastern-European intelligentsia that hoped to carry out the task they set themselves, to go to the people. Sierakowski: ‘He was an exceptionally engaged person. He worked himself to the bone, as a writer, as an intellectual and as an activist. He was a fascinating individual. Somebody once described his work as “philosophical vodka”, but his philosophy is deeply humanist. All Polish dissidents during communism, including Miłosz, were influenced by him.’

Brzozowski’s influence can also be felt today. ‘It’s the intelligentsia’s duty’, says Sierakowski, ‘to once more “go back to the people”, as it was called in the nineteenth century. We are living in an atomised world, so what do we need? Binding agent. If people are to get back to solving problems together, there needs to be commitment.’

Krytyka is part of a long Eastern-European tradition, Sierakowski continues, which Western Europeans don’t always find easy to comprehend. ‘The word “intelligentsia” originated here in Eastern Europe, in the mid-nineteenth century. The existence of the intelligentsia is a symptom of backwardness. These people wanted to compensate for the lack of strong institutions, institutions that the West did have: cities, universities, state-run institutions. In Poland’s case, there wasn’t even a state. So if people wanted an enlightened society, or if they wanted to stand up for labourers or women’s rights, it was essential to have a group of dedicated people who were willing to devote their existence to the realisation of their ideals – a classic job for the intelligentsia.’

“The goal of the intelligentsia should be a kind of successful suicide, that is to say: to eventually become obsolete”

With not a single leftist party represented in the Polish parliament, there is a need to fall back on alternative, extra-parliamentary organisation. ‘The Left in Poland is in difficulty because their body of ideas is still based on post-communism, which is essentially a reincarnation of the old idea — more democratic, and generally better than under the former communist regime, but still outmoded and not “left” in the modern sense of the word. Who joined the communist party in the nineteen-eighties? They weren’t left-wing people, their motivation was different: power and status, influence.’

Like most countries from the original Soviet bloc, Poland was extremely illiberal, Sierakowski contends, a direct result of the communist era. ‘Communism functioned as a deep freeze. People awoke at the beginning of the nineties without having experienced the slightest influence of feminism or the gay movement, so even a lot of the left-wing dissidents were still quite conservative socially speaking. To let new ideas catch on, you need to organise people, engage in conversation with them, and persist. First they’ll laugh at you. Then they’ll laugh at you again. Then they’ll still be laughing at you. But in the end, if you survive and are still standing, after considerable time you will be able to convince people.’

This emphasis on constant organisation – a process that takes place completely outside of the parliamentary context – is fundamental for the task Sierakowski sees for Krytyka: ‘If you work with people for years on end, especially outside of the big cities, you have to be committed. It eats up a lot of energy, but in the end you will succeed because you have been able to create common experiences. The first job at hand is to form a powerful committed citizenship. The higher levels can reform the basis, later Marxists were right when they identified the public discourse as an important tool to change society.’

Bearing Brzozowski in mind, Sierakowski believes that this job is one pre-eminently suited to artists, musicians and writers. It is the duty of the intellectual and writer, Brzozowski thought, to speak out for a better society, to stand up for individualism. From an early age onwards, Brzozowski was fascinated by Russian nineteenth-century literature and the ideas that were dicussed by writers like Dostoyevsky. In response to the latter’s novel Demons, Brzozowski wrote his own novel, Flames, in which he challenged Dostoyevsky’s gloomy worldview and launched an attack on the remains of feudal conservatism, tradition, clericalism and capitalism.

But what if Dostoyevsky’s ultimate vision about mankind were closer to the truth than the individualistic or humanistic left-wing ideal? What if people, after having laughed a fourth time at the activists who “go to the people”, keep laughing? What if they don’t want to be free in the way that others have in mind for them?

‘I consider Dostoyevsky as the most important challenger of left-wingers anywhere’, replies Sierakowski. ‘If you think you are left-wing, of if you want to be left-wing, you have to be willing to hold your ideas up to Dostoyevsky. He is a test. Look at Notes from Underground, and look at the bigger discussion that book was part of, between Chernyshevsky (with What Is to Be Done), Turgenev (Fathers and Sons) and Dostoyevsky himself.’

Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky (11 November 1821 – 9 February 1881), sometimes transliterated Dostoyevsky, was a Russian novelist, short story writer, essayist, journalist and philosopher. Dostoevsky's literary works explore human psychology in the troubled political, social, and spiritual atmospheres of 19th-century Russia, and engage with a variety of philosophical and religious themes.

The discussion that plays in the background in the works of Dostoyevsky and Turgenev was sparked by Chernyshevsky, who had sketched a rationalist utopia in What Is to Be Done, to benefit the Russian rural proletariat. Turgenev called his views nihilism and Dostoyevsky, for his part, struck back with the Underground Man. No matter how beautiful and salutary, how sensible the utopia is made out to be, the underground man doesn’t care for it – the only thing he holds on to with all his might is his autonomy, which is worth more to him than any plan or programme could ever be. That the price for his autonomy is great unhappiness doesn’t bother him; at least it’s his unhappiness. ‘In his Notes from Underground Dostoyevsky essentially argued that rational utopia probably doesn’t bring freedom. For myself the lesson is also that one should, ultimately, believe. When it comes down to it, you can’t let your ideas rest on some scientific groundwork. This also means, by the way, that you always have to be a bit suspicious of yourself.’

Ivan Sergeyevich Turgenev (October 28] 1818 – September 3, 1883) was a Russian novelist, short story writer, poet, playwright, translator and popularizer of Russian literature in the West.

Nikolay Gavrilovich Chernyshevsky (12 July 1828 – 17 October 1889) was a Russian revolutionary democrat, materialist philosopher, editor, critic, and socialist (seen by some as a utopian socialist). He was the leader of the revolutionary democratic movement of the 1860s, and had an influence on Vladimir Lenin, Emma Goldman, and Serbian political writer and socialist Svetozar Marković.

Turgenev belonged to the superfluous generation. The generation that did have some abstract ideals, but that ran up against the tyranny of Tsarist Russia. Sierakowski: ‘Today’s intelligentsia feels the same way. We are the superfluous people Turgenev wrote about. The goal of the intelligentsia should be a kind of successful suicide, that is to say: to eventually become obsolete, because society can solve its own social problems.’

The main thing is, in a word, dedication. Sierakowski quotes Brzozowski one last time. ‘He wrote: “What is not biography, is nothing.” This means that ideals are realised by living them. Through patience, mistakes, persistence and repetition. It’s the idea that you can’t fall back on abstract ideas without taking reality into account. You have to be sceptical. Whenever you try to implement abstractions – whatever they are: socialism, feminism – it always creates problems, and sometimes atrocities. Only shared experiences, political experiences, can cause people to change. Those who want to save politics should counter atomisation, and this means that connections between people need to be cultivated. That is the most effective antidote against distrust and cynicism – and we know: those two things are the main obstacles to reclaiming democracy.’

Further reading:

The Polish Threat to Europe by Sławomir Sierakowski (published on 19 January 2016 in Project Syndicate)

Sierakowski: No Freedom Without Solidarity! [Interview] (published on 22 January on Political Critique's website)

Krytyka Polityczna is one of the six hubs in ECF's Connected Action for the Commons programme.