Post by Bonobo on Nov 14, 2021 15:29:14 GMT 1

One of most important diary writers was

Jan Chryzostom Pasek of Gosławice (c.1636–1701) was a Polish nobleman and writer during the times of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. He is best remembered for his memoirs (Pamiętniki), which are a valuable historical source about Baroque sarmatian culture and events in the Commonwealth.[1]

Literary output

Towards the end of his life (around 1690-1695) Pasek wrote an autobiographical diary, Pamietniki, a copy of which was found in 18th century with extracts printed in 1821 and a full work published in 1836 by Edward Raczyński, making him posthumously famous. Since a number of opening pages of the first part and the final pages of the last part are missing, it is now impossible to establish when Pasek begins and ends his story. Furthermore, as he wrote the diary many years after these conflicts, he frequently mistook some historic events and incorporated incorrect dates into the text. However, there a numerous authentic details contained within the memoirs particularly from his military service and a collection of letters from the Kings and other nobles whom he served.

The diary is divided into two parts. The first part covers the years 1655–1666, describing wars with the Swedish Empire (Swedish invasion of Poland), Transylvania, Muscovy (Russo-Polish War (1654–67)) and Lubomirski's Rebellion. Pasek also describes the Polish army raid over Denmark (1658–1659). Altogether, Pasek fought in large parts of Europe, from Smolensk to Jutland, and from Gdańsk to Vienna. The second part of the book covers the years 1667–1688, when Pasek settled down in his village near Kraków in Lesser Poland. He describes his peacetime activities, conveniently missing some compromising facts, such as court orders, sentencing him to infamia. He did not object serfdom and peasant social class oppression. Representative of the late Sarmatism culture, he viewed the Szlachta as the only real representatives of Poland, but even then he invariably unfavourably described the actions of Lithuanian and Cossack nobles and neither did he spare Polish nobles from rebuke.

In his memoirs he depicts in vivid language the everyday life of a Polish noble (Szlachcic), during both war and peace. He appears to have written as he would have spoken, and it is this language and attitude which has been highlighted as his contribution to Polish literature (later inspiring the language written by Sienkiewicz for his characters in the Trilogy) and has made his memoirs considered to be the most interesting and entertaining Polish memoirs of the age. He commented on everything from the fashions of the time, the outcomes of duels and squabbles amongst the Szlachta, the passing of the seasons, the profitability of leaseholds and quality of harvests, domestic and international politics, as well as providing valuable descriptions of the battles he was involved in and of warfare at the time. His contemporary Jesuit education is evidenced by his use of classical and mythological rhetoric and his abundant use of Latin phrases within his writings.

His memoirs outline his attitude to the politics of the era. Himself devotedly loyal to Poland and to his country's King, but despairing at the situation the Commonwealth found itself in, the way the army conducted itself, and how successive treaties, rebellions, invasions and civil wars weakened the country. He hated the schemes of Archbishop Prażmowski ('the one eyed bishop who saw only evil') and Queen Ludwika to place a Frenchman on the throne of Poland, and rejoiced when the Diet elected Michał Wiśniowiecki and subsequently Jan Sobieski as King ('Vivat Piast') and recognised the problems that electing foreign Kings posed to the security and politics of the Commonwealth. While supportive of King John II Casimir (1648–68) he nerveless criticises the King's own role in the catastrophic last years of his reign. He is favourable of the actions of the largely incompetent rule of King Michael Korybut (1669–73), and concludes his narrative with splendid descriptions of the reign of King John III Sobieski (1674–96) and a vivid second-hand account of actions of the Polish army at the Siege of Vienna and their subsequent actions in Hungary. He mentions his own role in the Swedish and Muscovite wars and the politics surrounding them and writes colourfully about the military life, showing soldiers primary motivations, like curiosity, desire of fame and loot.

Illustration of a meeting of the Sejm described by Pasek

A devout Catholic, Pasek attributed many of the events he sees and the fortunes of the Commonwealth and its Hetmans to the 'Will of God'. He is a great believer in piety stating that God gave Czarniecki his victories as he devoted them to God and his King rather than taking credit for them himself. Despite this Pasek, by his own admission, frequently gets into quarrels with others, and shows disregard for non-Catholic Christian denominations; for example, he describes Polish soldiers stealing prayer books from faithful Danes during a service at a Lutheran church in Denmark, and the highlights rejection of Protestant souls from heaven as retribution by St. Peter for their desecration of Polish churches after an explosion at a besieged Swedish occupied castle threw the remaining defenders into the air before they fell into the nearby river.

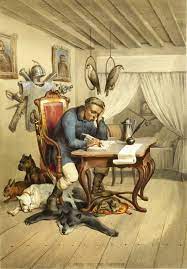

The memoirs provide many vivid details of Pasek's personal life. He offers wearied advice on marriage in light of his troubles after his marrying a widow with five step-daughters, and advises young men to take every chance they can to participate in local Diets in order to learn etiquette, law and politics. He details the many fights, duels and arguments that he is involved in, and gives a description of a theatrical performance in Warsaw in 1664 which descended into a massacre of the actors after one of his fellow fully-armed Szlachta mistakes an actor for the actual Emperor of Austria. He describes arguments during the Diets, his altercation with Ivan Mazepa which allegedly left Mazepa in tears, and his and his relations romantic lives. At one point in his later years he successfully trains an otter as a pet which will bring him fish from any river or pond on command, and goes hunting accompanied by a menagerie of hunting dogs, a fox, a martin, a badger, a hawk and a raven, all with a hare with bells on hopping behind him.

Pasek utilised different genres in his writing, such as:

lyric poetry (in a farewell to his beloved horse Deresz)

panegyrics (describing the victory in the Battle of Vienna and the Battle of Basya)

letters of King John II Casimir and Hetman Stefan Czarniecki

speeches and dialogues

popular songs of the era

satirical metaphors (describing the Hungarian invasion as an attempt to sate an appetite for garlic)

offensive jokes and mockery of almost all non-Poles (and may of his fellow Szlachta)

everyday language and swear words

Pasek's Pamiętniki are frequently compared to that of Samuel Pepys Diary though Pepys diary is more detailed and takes place over ten years in high Offices, Pasek's memoirs take place over thirty two years and are far broader and more down-to-earth in scope. However, there are significant difference between the experiences of the contemporaneous English aristocracy and the Commonwealth Szlachta in terms of what life was like and what 'nobility' meant. Other comparisons within English Literature have also been made with the works of Samuel Johnson and James Boswell

In 1896 the part of Pasek's memoirs that describes the Polish army campaign in Denmark was translated to Danish by Stanisław Rosznecki and published as the book Polakkerne i Danmark 1659 (The Poles in Denmark 1659).[3]

Cultural references

His diary has sometimes been called the “Epos of Sarmatian Poland”, and inspired a number of 19th and 20th century Polish writers, such as Adam Mickiewicz, Juliusz Słowacki, Henryk Sienkiewicz, Teodor Jeske-Choiński, Zygmunt Krasiński, Józef Ignacy Kraszewski and Witold Gombrowicz. Adam Mickiewicz devoted two of his lectures on Slavic literature to him; Juliusz Słowacki used his figure in "Mazepie", where the author of 'Memoirs' on the porch, 'With a serious parrot': "And he stood with a large piece of paper - well! he's a lovely speaker, he prepared a macaroon poem for the king."

Henryk Sienkiewicz made extensive use of the Pasek's vocabulary and most likely took the title of the first volume of his "Trilogy" (With Fire and Sword) from a line in Pasek's memoirs: "[the enemy] plundered three parts of our homeland with sword and fire ..." ([wróg] trzy części ojczyzny naszej mieczem i ogniem splądrował...).

His works inspired others including Zygmunt Krasiński, Józef Ignacy Kraszewski, Zygmunt Kaczkowski, Teodor Jeske-Choiński, and Henryk Rzewuski, who wrote a series of 'noble's' tales' published as "Memoirs of Soplica". Pasek's influence is also visible in the literature of the 20th century, e.g. in poetry Jerzy Harasymowicz, Ernest Bryll, in the novel "Trans-Atlantyk" (1953) Witold Gombrowicz (a parody of a noble's tales), in the stories of the author of "Szczenięcych lat" Melchior Wańkowicz, and in the work of Ksawery Pruszyński and Wojciech Żukrowski. Numerous references to Pasek's diaries show the inspirational roots of Polish artists in the national culture of the 17th-century Commonwealth.

Jan Chryzostom Pasek of Gosławice (c.1636–1701) was a Polish nobleman and writer during the times of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. He is best remembered for his memoirs (Pamiętniki), which are a valuable historical source about Baroque sarmatian culture and events in the Commonwealth.[1]

Literary output

Towards the end of his life (around 1690-1695) Pasek wrote an autobiographical diary, Pamietniki, a copy of which was found in 18th century with extracts printed in 1821 and a full work published in 1836 by Edward Raczyński, making him posthumously famous. Since a number of opening pages of the first part and the final pages of the last part are missing, it is now impossible to establish when Pasek begins and ends his story. Furthermore, as he wrote the diary many years after these conflicts, he frequently mistook some historic events and incorporated incorrect dates into the text. However, there a numerous authentic details contained within the memoirs particularly from his military service and a collection of letters from the Kings and other nobles whom he served.

The diary is divided into two parts. The first part covers the years 1655–1666, describing wars with the Swedish Empire (Swedish invasion of Poland), Transylvania, Muscovy (Russo-Polish War (1654–67)) and Lubomirski's Rebellion. Pasek also describes the Polish army raid over Denmark (1658–1659). Altogether, Pasek fought in large parts of Europe, from Smolensk to Jutland, and from Gdańsk to Vienna. The second part of the book covers the years 1667–1688, when Pasek settled down in his village near Kraków in Lesser Poland. He describes his peacetime activities, conveniently missing some compromising facts, such as court orders, sentencing him to infamia. He did not object serfdom and peasant social class oppression. Representative of the late Sarmatism culture, he viewed the Szlachta as the only real representatives of Poland, but even then he invariably unfavourably described the actions of Lithuanian and Cossack nobles and neither did he spare Polish nobles from rebuke.

In his memoirs he depicts in vivid language the everyday life of a Polish noble (Szlachcic), during both war and peace. He appears to have written as he would have spoken, and it is this language and attitude which has been highlighted as his contribution to Polish literature (later inspiring the language written by Sienkiewicz for his characters in the Trilogy) and has made his memoirs considered to be the most interesting and entertaining Polish memoirs of the age. He commented on everything from the fashions of the time, the outcomes of duels and squabbles amongst the Szlachta, the passing of the seasons, the profitability of leaseholds and quality of harvests, domestic and international politics, as well as providing valuable descriptions of the battles he was involved in and of warfare at the time. His contemporary Jesuit education is evidenced by his use of classical and mythological rhetoric and his abundant use of Latin phrases within his writings.

His memoirs outline his attitude to the politics of the era. Himself devotedly loyal to Poland and to his country's King, but despairing at the situation the Commonwealth found itself in, the way the army conducted itself, and how successive treaties, rebellions, invasions and civil wars weakened the country. He hated the schemes of Archbishop Prażmowski ('the one eyed bishop who saw only evil') and Queen Ludwika to place a Frenchman on the throne of Poland, and rejoiced when the Diet elected Michał Wiśniowiecki and subsequently Jan Sobieski as King ('Vivat Piast') and recognised the problems that electing foreign Kings posed to the security and politics of the Commonwealth. While supportive of King John II Casimir (1648–68) he nerveless criticises the King's own role in the catastrophic last years of his reign. He is favourable of the actions of the largely incompetent rule of King Michael Korybut (1669–73), and concludes his narrative with splendid descriptions of the reign of King John III Sobieski (1674–96) and a vivid second-hand account of actions of the Polish army at the Siege of Vienna and their subsequent actions in Hungary. He mentions his own role in the Swedish and Muscovite wars and the politics surrounding them and writes colourfully about the military life, showing soldiers primary motivations, like curiosity, desire of fame and loot.

Illustration of a meeting of the Sejm described by Pasek

A devout Catholic, Pasek attributed many of the events he sees and the fortunes of the Commonwealth and its Hetmans to the 'Will of God'. He is a great believer in piety stating that God gave Czarniecki his victories as he devoted them to God and his King rather than taking credit for them himself. Despite this Pasek, by his own admission, frequently gets into quarrels with others, and shows disregard for non-Catholic Christian denominations; for example, he describes Polish soldiers stealing prayer books from faithful Danes during a service at a Lutheran church in Denmark, and the highlights rejection of Protestant souls from heaven as retribution by St. Peter for their desecration of Polish churches after an explosion at a besieged Swedish occupied castle threw the remaining defenders into the air before they fell into the nearby river.

The memoirs provide many vivid details of Pasek's personal life. He offers wearied advice on marriage in light of his troubles after his marrying a widow with five step-daughters, and advises young men to take every chance they can to participate in local Diets in order to learn etiquette, law and politics. He details the many fights, duels and arguments that he is involved in, and gives a description of a theatrical performance in Warsaw in 1664 which descended into a massacre of the actors after one of his fellow fully-armed Szlachta mistakes an actor for the actual Emperor of Austria. He describes arguments during the Diets, his altercation with Ivan Mazepa which allegedly left Mazepa in tears, and his and his relations romantic lives. At one point in his later years he successfully trains an otter as a pet which will bring him fish from any river or pond on command, and goes hunting accompanied by a menagerie of hunting dogs, a fox, a martin, a badger, a hawk and a raven, all with a hare with bells on hopping behind him.

Pasek utilised different genres in his writing, such as:

lyric poetry (in a farewell to his beloved horse Deresz)

panegyrics (describing the victory in the Battle of Vienna and the Battle of Basya)

letters of King John II Casimir and Hetman Stefan Czarniecki

speeches and dialogues

popular songs of the era

satirical metaphors (describing the Hungarian invasion as an attempt to sate an appetite for garlic)

offensive jokes and mockery of almost all non-Poles (and may of his fellow Szlachta)

everyday language and swear words

Pasek's Pamiętniki are frequently compared to that of Samuel Pepys Diary though Pepys diary is more detailed and takes place over ten years in high Offices, Pasek's memoirs take place over thirty two years and are far broader and more down-to-earth in scope. However, there are significant difference between the experiences of the contemporaneous English aristocracy and the Commonwealth Szlachta in terms of what life was like and what 'nobility' meant. Other comparisons within English Literature have also been made with the works of Samuel Johnson and James Boswell

In 1896 the part of Pasek's memoirs that describes the Polish army campaign in Denmark was translated to Danish by Stanisław Rosznecki and published as the book Polakkerne i Danmark 1659 (The Poles in Denmark 1659).[3]

Cultural references

His diary has sometimes been called the “Epos of Sarmatian Poland”, and inspired a number of 19th and 20th century Polish writers, such as Adam Mickiewicz, Juliusz Słowacki, Henryk Sienkiewicz, Teodor Jeske-Choiński, Zygmunt Krasiński, Józef Ignacy Kraszewski and Witold Gombrowicz. Adam Mickiewicz devoted two of his lectures on Slavic literature to him; Juliusz Słowacki used his figure in "Mazepie", where the author of 'Memoirs' on the porch, 'With a serious parrot': "And he stood with a large piece of paper - well! he's a lovely speaker, he prepared a macaroon poem for the king."

Henryk Sienkiewicz made extensive use of the Pasek's vocabulary and most likely took the title of the first volume of his "Trilogy" (With Fire and Sword) from a line in Pasek's memoirs: "[the enemy] plundered three parts of our homeland with sword and fire ..." ([wróg] trzy części ojczyzny naszej mieczem i ogniem splądrował...).

His works inspired others including Zygmunt Krasiński, Józef Ignacy Kraszewski, Zygmunt Kaczkowski, Teodor Jeske-Choiński, and Henryk Rzewuski, who wrote a series of 'noble's' tales' published as "Memoirs of Soplica". Pasek's influence is also visible in the literature of the 20th century, e.g. in poetry Jerzy Harasymowicz, Ernest Bryll, in the novel "Trans-Atlantyk" (1953) Witold Gombrowicz (a parody of a noble's tales), in the stories of the author of "Szczenięcych lat" Melchior Wańkowicz, and in the work of Ksawery Pruszyński and Wojciech Żukrowski. Numerous references to Pasek's diaries show the inspirational roots of Polish artists in the national culture of the 17th-century Commonwealth.