Post by Bonobo on Jan 4, 2022 17:49:20 GMT 1

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Somosierra

The Battle of Somosierra took place on 30 November 1808, during the Peninsular War, when a combined Franco-Spanish-Polish force under the direct command of Napoleon Bonaparte forced a passage through against Spanish guerrillas stationed at the Sierra de Guadarrama which was shielding Madrid from direct French attack. At the Somosierra mountain pass, 60 miles north of Madrid, a heavily outnumbered Spanish detachment of conscripts and artillery under Benito de San Juan aimed to block Napoleon's advance on the Spanish capital. Napoleon overwhelmed the Spanish positions in a combined arms attack, sending the Polish Chevau-légers of the Imperial Guard at the Spanish guns while French infantry advanced up the slopes. The victory removed the last obstacle barring the road to Madrid, which fell several days later.[2]

Polemical discussion about the romantic Polish attitude, well-shown in the battle:

www.onet.pl/informacje/krowoderskapl/ta-bitwa-jest-symbolem-najgorszych-cech-polakow-a-powinna-byc-najlepszych/qdfycrl,30bc1058

This battle is a symbol of the worst traits of Poles. And it should be the best

- What a boldness in these Poles! Napoleon Bonaparte repeated again and again, watching the effect of the Battle of Somosierra. The daring, insane charge performed by the Polish cavalrymen at that time, opened the way for the imperial army to Madrid. Nevertheless, care was taken that we did not remember her very well. And the symbol of Polish courage was turned into an example of our bravado.

Tomasz Borejza

11.6 thousand

December 21, 2021, 20:20

Unnecessary bravado, it should be added.

However, it was not always this way. The day after the battle, when a regiment of Polish cavalrymen was passing the French infantry camp, the soldiers stood under arms on their own initiative and shouted: "Long live the brave!" When Napoleon saw this, he ordered the lightly horse to form an array, took off his hat and exclaimed: "Hello, bravest of the brave!" And a few decades later, the memory of the exceptional courage of our cavalrymen was so vivid that Bismarck set them as an example.

There is an anecdote (as quoted by Marian Brandys in the book "Kozietulski and others") about a staff meeting held several dozen years later at the Iron Chancellor. There, Prussian officers downplayed the cavalry's feat, arguing that horses had been carried away at Somosierra. To which Bismarck put them out, saying: "It is possible that the horses were carried away. But if there are cowards on horses, they carry them backwards. But when the brave sit on them, they carry them forward - to the enemy."

Battle of Somosierra

The legend was well deserved. The charge in the Somosierry Gorge required tremendous courage. The Poles were charging along a narrow road that they could not even develop their formation on the fortified artillery positions of the Spaniards. However, it was not without sense. "The emperor would have conquered the Somosierry ravine without fail," argued Józef Załuski, "on foot, but it would have cost several thousand killed and wounded, when the impetus by cavalry did not bring a loss of a hundred people."

The battle was fought in 1808 during Napoleon's Spanish campaign. It was important because the success opened the way for the imperial army to Madrid. But it was also insanely difficult. The pass was at an altitude of over 1,400 meters above sea level. They were charged uphill, with Spanish cannons loaded. The clearances were over 200 meters. "The road narrowed in this ravine", Załuski reported, "wound on a slope between the rocks, manned with infantry, and on its four bends there were four guns that fired at it in all its directions." The staff did not believe in success.

"Drunk like a Pole" is a compliment

And yet it worked.

There are as many reports about what happened before and after the battle as about what happened during it. Anecdote follows an anecdote in them. Marshal Berthier was telling Napoleon that the gorge could not be conquered by a cavalry charge. The emperor only replied: "Leave it to the Poles!" And Marian Brandys wrote: "Another version - not very likely - proclaims that one of the generals, hearing the imperial order, allowed himself to remark: 'You have to be drunk to give such an order, and you have to be drunk to carry out such an order!' After the charge the emperor was informed about it, he was said to say: "I wish that all my soldiers were as drunk as these Poles!"

Somosierra: "Taking half-batteries of cannons one by one" Napoleon knew his Polish guards and he knew - his contemporaries argued - that they perceive themselves as a representation of a nation that places its hopes for independence in the emperor. And as such, they will do their best not to disappoint and bring shame. Even when others will perceive their task as certain death. He was not mistaken.

When Jan Kozietulski received the charge order, he prepared a squadron. He exclaimed "long live the emperor!" And together with his subordinates he moved to the Spanish positions. - As soon as the attack began, it continued uninterrupted, capturing cannon half-batteries one by one - described Józef Załuski.

Eight minutes and 2,500 meters away, the last Spanish fortification was smashed. Of the 125 cavalrymen taking part in the attack, 22 were killed, and another 35 were seriously wounded. A dozen or so cannons were captured, and the successful charge resulted in the capture of - it is estimated - several thousand Spaniards.

Kozietulszczyzna !?

"The moral effect of the charge," Brandys wrote, "was enormous. The panic of the fleeing troops disarmed all of Castile. Further resistance from the Spaniards became almost impossible. The road to Madrid was open to the victors." Pretty good for eight minutes of battle, huh?

And yet not. While initially Cheval Legers from Somosierra were worshiped, with time they became a symbol of what was bad in Poles. The term "kozietulszczyzna" was even coined, which symbolized our national inclination to bravado, unnecessary risk, and sacrifice valued higher than work. Finally, that we tend to achieve small victories at great cost.

It came about that there was such a need for a moment. It was created in the People's Republic of Poland at the turn of the 1950s and 1960s. But it was done using an earlier tradition. Socialist Poland, whose system was guaranteed by an external power, did not need people's fantasies and an inclination to take risks. She certainly did not want the insurgents. She needed polite and polite citizens. People who will build a new reality without asking many questions.

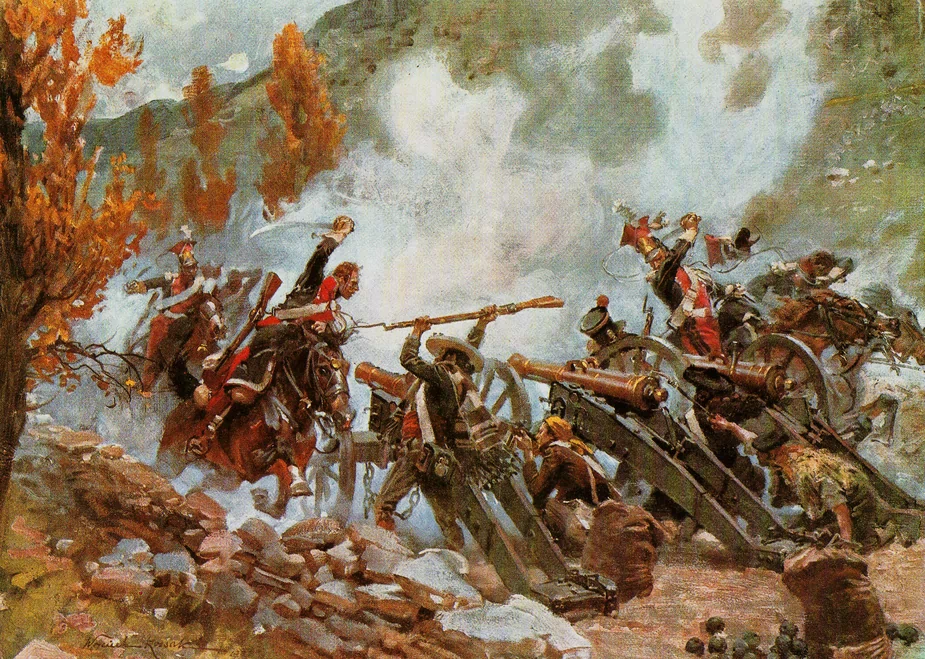

Battle of Somosierra, in the painting by Horace Vernet. Battle of Somosierra, in the painting by Horace Vernet. - Wikimedia Commons / Krowoderska.pl

Romanticism vs positivism

In order to educate such citizens, appropriate models had to be found in culture. It wasn't hard. Perfectly suited for this was the use of the opposition of Polish bravado leading to senseless uprisings and sacrifices from subsequent generations, positivism and organic work, which, although less romantic, brought better results, dating back to the time of the partitions. The thing has become a part of the canon of Polish schools and culture for good.

I would even say that she entered the national bloodstream.

The division on which it is based is still alive today and affects how we perceive ourselves. We got used to it so much that it turned transparent. So much so that we don't even see him anymore. We like - or at least some journalists like it, because I, for example, do not like it - in stigmatizing Polish laziness, the ability to mobilize only in exceptional situations, bravado and general shortcomings in relation to the so-called West.

For example, it is emphasized that Poles are a wonderful nation, but only in a crisis. Because on a daily basis - some people shake their noses - not so much anymore. At the same time, usually sighing to the calm and ordered societies of Europe. The source of such an image and what makes it socially viable is, among other things, that we have been taught to look negatively at various "Somosierry".

Read also: A Pole who is worth knowing and almost nobody remembers about him. His name is on the Arc de Triomphe

Either or?

Good narrative requires that it be grounded in facts and needs. This one caught on because she had them. It was quite an accurate answer to the partitions. (And the later years of the Second World War and the People's Republic of Poland and the People's Republic of Poland dependent on Moscow). At that time, it was impossible to combine bravado with work. It was possible to do only as much as the invaders allowed. And they allowed for a bit of independence only when they believed that they had allies in the Poles, or at least they did not threaten them.

As a result, the rising romantics were a threat to grassroots workers. There are many examples. For example, the reforms of Franciszek Ksawery Drucki-Lubecki, who, taking advantage of the limited freedoms provided by Congress Poland, tried to do as much as possible and build the Polish economy within the partition of the partitioning state.

So that Poland - if it ever recovered - would have its industry and money.

His work, however, collapsed when the November Uprising broke out.

And it happened again and again. On a smaller or larger scale.

Through this we have learned - and we have been taught it in school for decades - that Polish Romanticism and positivism are like "plus" and "minus". Either we decide on one or the other. Or we'll die throwing at the cannons like the light cavalry from Somosierra. Or we will slowly and calmly learn not to lean out and build something valuable step by step. Or. Or.

It is impossible to connect with the other. Truth?

A new reading of history for new times

Just not true. Perhaps it was not possible in the nineteenth century. Probably also for most of the 20th century. But today times have changed. You no longer need to hide from the invaders. A hint of bravado and lazy fantasy in building lasting and valuable things does not have to be disturbing, but can rather help. And anything we've been taught to see as national shortcomings might as well be an advantage. What distinguishes us from the tired and organized welfare societies that can be seen today almost all over Western Europe. It is also possible to look at rebelliousness in this way. And the tendency to abandon the beaten path and look for our own. Reluctance to give up blindly to what belongs and belongs to, because others do. And even bravado, which we can bring ourselves to where others cannot. Often with very good results. Just like in Somosierra.

Even among the cavalrymen who fought there, you can find people who combined bravado and the ability to produce sustainable organic work. But about that another time.

Now is the time to ask whether what we have been taught to see as national faults is not today rather national virtues?

Szwoleżer Jan Kozietulski would be a perfect patron of such a discussion.

Read also: Stańczyk. If Zygmunt Stary had listened to him, there would be no partitions

Tomasz Borejza is a science journalist, deputy editor-in-chief of the SmogLab.pl website. He publishes or has published, inter alia, in Tygodnik Przegląd, Przekrój, Gazeta Krakowska, Coolture and trade magazines. On Krowoderska.pl, he blogs about Krakow and its history.

Source:

Krowoderska.pl

Date Created: December 21, 2021, 20:20

The Battle of Somosierra took place on 30 November 1808, during the Peninsular War, when a combined Franco-Spanish-Polish force under the direct command of Napoleon Bonaparte forced a passage through against Spanish guerrillas stationed at the Sierra de Guadarrama which was shielding Madrid from direct French attack. At the Somosierra mountain pass, 60 miles north of Madrid, a heavily outnumbered Spanish detachment of conscripts and artillery under Benito de San Juan aimed to block Napoleon's advance on the Spanish capital. Napoleon overwhelmed the Spanish positions in a combined arms attack, sending the Polish Chevau-légers of the Imperial Guard at the Spanish guns while French infantry advanced up the slopes. The victory removed the last obstacle barring the road to Madrid, which fell several days later.[2]

Polemical discussion about the romantic Polish attitude, well-shown in the battle:

www.onet.pl/informacje/krowoderskapl/ta-bitwa-jest-symbolem-najgorszych-cech-polakow-a-powinna-byc-najlepszych/qdfycrl,30bc1058

This battle is a symbol of the worst traits of Poles. And it should be the best

- What a boldness in these Poles! Napoleon Bonaparte repeated again and again, watching the effect of the Battle of Somosierra. The daring, insane charge performed by the Polish cavalrymen at that time, opened the way for the imperial army to Madrid. Nevertheless, care was taken that we did not remember her very well. And the symbol of Polish courage was turned into an example of our bravado.

Tomasz Borejza

11.6 thousand

December 21, 2021, 20:20

Unnecessary bravado, it should be added.

However, it was not always this way. The day after the battle, when a regiment of Polish cavalrymen was passing the French infantry camp, the soldiers stood under arms on their own initiative and shouted: "Long live the brave!" When Napoleon saw this, he ordered the lightly horse to form an array, took off his hat and exclaimed: "Hello, bravest of the brave!" And a few decades later, the memory of the exceptional courage of our cavalrymen was so vivid that Bismarck set them as an example.

There is an anecdote (as quoted by Marian Brandys in the book "Kozietulski and others") about a staff meeting held several dozen years later at the Iron Chancellor. There, Prussian officers downplayed the cavalry's feat, arguing that horses had been carried away at Somosierra. To which Bismarck put them out, saying: "It is possible that the horses were carried away. But if there are cowards on horses, they carry them backwards. But when the brave sit on them, they carry them forward - to the enemy."

Battle of Somosierra

The legend was well deserved. The charge in the Somosierry Gorge required tremendous courage. The Poles were charging along a narrow road that they could not even develop their formation on the fortified artillery positions of the Spaniards. However, it was not without sense. "The emperor would have conquered the Somosierry ravine without fail," argued Józef Załuski, "on foot, but it would have cost several thousand killed and wounded, when the impetus by cavalry did not bring a loss of a hundred people."

The battle was fought in 1808 during Napoleon's Spanish campaign. It was important because the success opened the way for the imperial army to Madrid. But it was also insanely difficult. The pass was at an altitude of over 1,400 meters above sea level. They were charged uphill, with Spanish cannons loaded. The clearances were over 200 meters. "The road narrowed in this ravine", Załuski reported, "wound on a slope between the rocks, manned with infantry, and on its four bends there were four guns that fired at it in all its directions." The staff did not believe in success.

"Drunk like a Pole" is a compliment

And yet it worked.

There are as many reports about what happened before and after the battle as about what happened during it. Anecdote follows an anecdote in them. Marshal Berthier was telling Napoleon that the gorge could not be conquered by a cavalry charge. The emperor only replied: "Leave it to the Poles!" And Marian Brandys wrote: "Another version - not very likely - proclaims that one of the generals, hearing the imperial order, allowed himself to remark: 'You have to be drunk to give such an order, and you have to be drunk to carry out such an order!' After the charge the emperor was informed about it, he was said to say: "I wish that all my soldiers were as drunk as these Poles!"

Somosierra: "Taking half-batteries of cannons one by one" Napoleon knew his Polish guards and he knew - his contemporaries argued - that they perceive themselves as a representation of a nation that places its hopes for independence in the emperor. And as such, they will do their best not to disappoint and bring shame. Even when others will perceive their task as certain death. He was not mistaken.

When Jan Kozietulski received the charge order, he prepared a squadron. He exclaimed "long live the emperor!" And together with his subordinates he moved to the Spanish positions. - As soon as the attack began, it continued uninterrupted, capturing cannon half-batteries one by one - described Józef Załuski.

Eight minutes and 2,500 meters away, the last Spanish fortification was smashed. Of the 125 cavalrymen taking part in the attack, 22 were killed, and another 35 were seriously wounded. A dozen or so cannons were captured, and the successful charge resulted in the capture of - it is estimated - several thousand Spaniards.

Kozietulszczyzna !?

"The moral effect of the charge," Brandys wrote, "was enormous. The panic of the fleeing troops disarmed all of Castile. Further resistance from the Spaniards became almost impossible. The road to Madrid was open to the victors." Pretty good for eight minutes of battle, huh?

And yet not. While initially Cheval Legers from Somosierra were worshiped, with time they became a symbol of what was bad in Poles. The term "kozietulszczyzna" was even coined, which symbolized our national inclination to bravado, unnecessary risk, and sacrifice valued higher than work. Finally, that we tend to achieve small victories at great cost.

It came about that there was such a need for a moment. It was created in the People's Republic of Poland at the turn of the 1950s and 1960s. But it was done using an earlier tradition. Socialist Poland, whose system was guaranteed by an external power, did not need people's fantasies and an inclination to take risks. She certainly did not want the insurgents. She needed polite and polite citizens. People who will build a new reality without asking many questions.

Battle of Somosierra, in the painting by Horace Vernet. Battle of Somosierra, in the painting by Horace Vernet. - Wikimedia Commons / Krowoderska.pl

Romanticism vs positivism

In order to educate such citizens, appropriate models had to be found in culture. It wasn't hard. Perfectly suited for this was the use of the opposition of Polish bravado leading to senseless uprisings and sacrifices from subsequent generations, positivism and organic work, which, although less romantic, brought better results, dating back to the time of the partitions. The thing has become a part of the canon of Polish schools and culture for good.

I would even say that she entered the national bloodstream.

The division on which it is based is still alive today and affects how we perceive ourselves. We got used to it so much that it turned transparent. So much so that we don't even see him anymore. We like - or at least some journalists like it, because I, for example, do not like it - in stigmatizing Polish laziness, the ability to mobilize only in exceptional situations, bravado and general shortcomings in relation to the so-called West.

For example, it is emphasized that Poles are a wonderful nation, but only in a crisis. Because on a daily basis - some people shake their noses - not so much anymore. At the same time, usually sighing to the calm and ordered societies of Europe. The source of such an image and what makes it socially viable is, among other things, that we have been taught to look negatively at various "Somosierry".

Read also: A Pole who is worth knowing and almost nobody remembers about him. His name is on the Arc de Triomphe

Either or?

Good narrative requires that it be grounded in facts and needs. This one caught on because she had them. It was quite an accurate answer to the partitions. (And the later years of the Second World War and the People's Republic of Poland and the People's Republic of Poland dependent on Moscow). At that time, it was impossible to combine bravado with work. It was possible to do only as much as the invaders allowed. And they allowed for a bit of independence only when they believed that they had allies in the Poles, or at least they did not threaten them.

As a result, the rising romantics were a threat to grassroots workers. There are many examples. For example, the reforms of Franciszek Ksawery Drucki-Lubecki, who, taking advantage of the limited freedoms provided by Congress Poland, tried to do as much as possible and build the Polish economy within the partition of the partitioning state.

So that Poland - if it ever recovered - would have its industry and money.

His work, however, collapsed when the November Uprising broke out.

And it happened again and again. On a smaller or larger scale.

Through this we have learned - and we have been taught it in school for decades - that Polish Romanticism and positivism are like "plus" and "minus". Either we decide on one or the other. Or we'll die throwing at the cannons like the light cavalry from Somosierra. Or we will slowly and calmly learn not to lean out and build something valuable step by step. Or. Or.

It is impossible to connect with the other. Truth?

A new reading of history for new times

Just not true. Perhaps it was not possible in the nineteenth century. Probably also for most of the 20th century. But today times have changed. You no longer need to hide from the invaders. A hint of bravado and lazy fantasy in building lasting and valuable things does not have to be disturbing, but can rather help. And anything we've been taught to see as national shortcomings might as well be an advantage. What distinguishes us from the tired and organized welfare societies that can be seen today almost all over Western Europe. It is also possible to look at rebelliousness in this way. And the tendency to abandon the beaten path and look for our own. Reluctance to give up blindly to what belongs and belongs to, because others do. And even bravado, which we can bring ourselves to where others cannot. Often with very good results. Just like in Somosierra.

Even among the cavalrymen who fought there, you can find people who combined bravado and the ability to produce sustainable organic work. But about that another time.

Now is the time to ask whether what we have been taught to see as national faults is not today rather national virtues?

Szwoleżer Jan Kozietulski would be a perfect patron of such a discussion.

Read also: Stańczyk. If Zygmunt Stary had listened to him, there would be no partitions

Tomasz Borejza is a science journalist, deputy editor-in-chief of the SmogLab.pl website. He publishes or has published, inter alia, in Tygodnik Przegląd, Przekrój, Gazeta Krakowska, Coolture and trade magazines. On Krowoderska.pl, he blogs about Krakow and its history.

Source:

Krowoderska.pl

Date Created: December 21, 2021, 20:20