|

|

Post by Bonobo on Feb 26, 2008 22:35:14 GMT 1

In 1944 the Soviet Army entered Eastern Poland. Due to the secret deal with Western powers, Stalin, the communist dictator of the Soviet Union, was allowed to grab Poland for himself and install there a communist regime.

Poles were unaware of the situation and deals. They thought that their fight against Germans, and later on against Russians, would save Poland from communism. Poles presumed it possible from their history: once a miracle happened and Poland was saved from invading barbaric Soviet hordes in 1920.

Unfortunately, this time the conditions were extremely unfavourable. Poland was doomed and nothing could save her.

Many Poles of low classes fraternised with the new regime, in hope for new positions, powers, money. They became its stooges, henchmen and hangmen, executors of orders given directly by Soviet patrons. Some of them really believed that communism would change the things for better in Poland and they were the most dangerous fanatics.

Yet, other patriotic Poles decided to resist. There weren`t many of them. After the failure of Warsaw Rising it was commonly agreed that the further bloodshed had to be stopped in order to save the nation`s substance. Poland lost millions of people during the war, 200.000 of them in Warsaw Rising alone. Adding to it even more victims of anticommunist resistance would be madness.

|

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Mar 5, 2008 20:32:08 GMT 1

AK, the Home Army, was the biggest underground organization in Europe during WW2. When the war finished, its commanders dissolved it and let the soldiers go home. Communists couldn`t allow those people remain where they were. They were too patriotic and as such posed a serious danger to the new regime. That`s how Soviets and Polish stooges dealt with AK. The first Polish communist government, PKWN, was formed in July 1944, but declined jurisdiction over AK soldiers. Consequently, for more than a year, it was Soviet agencies like the NKVD that dealt with the AK. By the end of the war, approximately 60,000 soldiers of the AK had been arrested, and 50,000 of them were deported to the Soviet Union's gulags and prisons. Most of those soldiers had been captured by the Soviets during or in the aftermath of Operation Tempest, when many AK units tried to cooperate with the Soviets in a nationwide uprising against the Germans. Other veterans were arrested when they decided to approach the government after being promised amnesty. In 1947, an amnesty was passed for most of the partisans; the Communist authorities expected around 12,000 people to give up their arms, but the actual number of people to come out of the forests eventually reached 53,000. Many of them were arrested despite promises of freedom; after repeated broken promises during the first few years of communist control, AK soldiers stopped trusting the government. In the period of 1944–56, approximately two million people were arrested, and over 20,000 (including Witold Pilecki, the hero of Auschwitz) were executed or murdered in communist prisons. A further six million Polish citizens (i.e., one out of every three adult Poles) were classified as suspected members of a 'reactionary or criminal element' and subjected to investigation by state agencies. In 1956, an amnesty released 35,000 former AK soldiers from prisons. For the crime of fighting for their homeland, they had spent 10 years or more years in prison. Still, some partisans remained in the countryside, unwilling or simply unable to rejoin the community. They became known as the cursed soldiers. Stanisław Marchewska ("Ryba") was killed in 1957, and the last AK partisan, Józef Franczak ("Lalek"), was killed in 1963 — almost two decades after the Second World War ended. It was only four years later, in 1967, that Adam Boryczka, a soldier of the AK and a member of the elite, British-trained Cichociemny ("The Silent and Hidden") intelligence and support group, was released from prison. Until the end of the People's Republic of Poland, AK soldiers were under investigation by the secret police, and it was only in 1989, after the fall of communism, that the sentences of AK soldiers were finally declared invalid and annulled by the Polish courtsThese underground soldiers who fought against Germans through WW2 were either killed in action after WW2 or murdered in communist prisons without trial, only one died a natural death in 1992.  5 accused soldiers were sentenced to death and executed in 1947.   They didn`t put down their arms.... pictures taken in August 1945.   The last anticommunist fighter wase killed in 1963. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/J%C3%B3zef_Franczak

Finally, in 1963, he was betrayed by a relative of his common law wife, Danuta Mazur. Stanislaw Mazur informed the secret police of Franczak's whereabouts and his planned meeting with Danuta Mazur, who was also the mother of his child. On 21 October 1963, 35 functionaries of ZOMO (a paramilitary riot police) unit surrounded a barn in Majdan Kozic Górnych, a village where Franczak was in hiding. They demanded his surrender; Franczak presented himself as a local peasant, but after having been asked about identity documents, he opened fire and was mortally wounded in the ensuing firefight. After an autopsy, Franczak's body (without its head), was returned to his family. He was buried in the cemetery in Piaski Wielkie.

|

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Mar 5, 2008 20:57:54 GMT 1

One of the soldiers who survived:

Antoni Heda (October 11, 1916 - February 15, 2008) was a Polish military commander and a notable veteran of the Polish resistance movement in World War II and later independence movement against Soviet occupation following the war. Among the best known of his partisan actions was the raid on Communist prison in Kielce in August of 1945, in which roughly 300 political prisoners were freed. His codename was "Szary" (Grey).

After the Soviet-backed Polish communist takeover of Poland, Heda - as a former prisoner of the NKVD - had to remain in hiding and joined the Ruch Oporu Armii Krajowej, one of splinter organizations formed after the Home Army had been disbanded. Later on he joined NIE and then yet another resistance organization Freedom and Independence (WiN). As a leader of a separate unit, Heda led yet another assault on a prison, this time on a MBP and Smersh prison in Kielce overnight of August 4, 1945. As a result, the partisans managed to liberate several hundred political prisoners, mostly former members of the Home Army.

Heda was using a false identity (Antoni Wiśniewski) but the UB security forces managed to discover Heda's identity and arrested his family. Soon afterwards two of his brothers and his brother-in-law were tortured to death. Heda planned to organize a similar assault on the infamous Rakowiecka prison in Warsaw, but he was arrested by the forces of the Internal Security Corps in 1948 in Gdynia. Imprisoned at Rakowiecka and later in Rawicz and Wronki, Heda was sentenced to death on 7 consecutive charges, but his sentence was later changed to life imprisonment.

After the end of Stalinist period in 1956 he was pardoned and set free. He continued to collaborate with various groups opposed to the Communist regime in Poland and was also an active member of unofficial veterans associations. In 1980 he joined the Solidarity and the following year he was chosen as the chairman of the Independent Veteran Association of the Solidarity, the first veteran association not controlled by the Communist authorities. However, soon afterwards he had been interned after the 1981 imposition of martial Law in Poland.

After Poland managed to get back its independence from the Eastern Bloc, in 1990 Heda returned to service as a leader of one of veteran associations uniting veterans of all fronts of the World War II. He also became the honorary commander of the Riflemen Union, a rightist paramilitary youth organization. On May 3, 2006 he was promoted to the rank of generał brygady (he received the nomination in 2004 and accepted it in 2006). For his service he also received the highest of Polish military awards, Virtuti Militari (4th and 5th class), as well as Krzyż Walecznych and other decorations.

He described his life in two books: Wspomnienia Szarego (Szary's Memoires) and Szary przeciw zdrajcom Polski (Szary against traitors of Poland).Pre-war and war photos of Heda   1943, Heda organised a few successful attacks on German occupants` prisons and freed hundreds of Poles.  A family visit to the forest hiding place, Heda on the left.  The guy looks so delicate and unasuming but he had the guts. Germans and communist stooges experienced it themselves.  1945, the photo taken before his most spectacular action, the attack on communist prison in Kielce, where over 300 political prisoners were freed.  Trying to capture him, the communist secret police arrested and murdered his two brothers.  He wrote a book  His last photo  |

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Mar 19, 2008 22:24:22 GMT 1

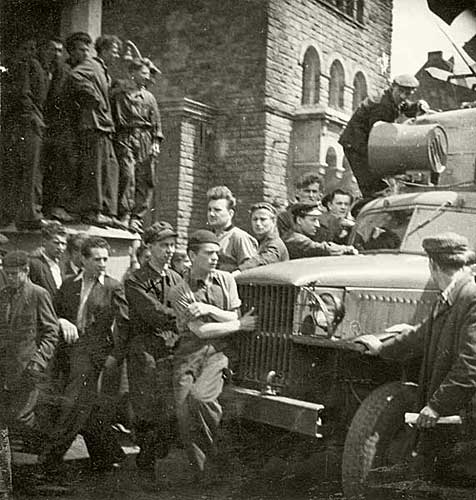

June 28, 1956 is another important date in the history of Poland. Exactly 50 years ago there was a revolt in the city of Poznań. Today many historians tend to call it 1956 Rising. **********

In the mid-1950s, following Stalin's death, the communist system imposed on the Central and Eastern Europe ceased to be a monolith. The changes under way in the USSR have forced the communist authorities in Poland to review their policy. The first attempts at criticizing the "security", the much-hated pillar of the communist power in Poland led to loosening the grip of a psychosis of fear.

The contempt for Stalinism and willingness to overcome "the period of mistakes and perversions" coincided in Poznań with the dissatisfaction with both living and working conditions, which had been building up since early 1950s. Wielkopolska, like the rest of country, was subject to a mandatory adjustment of all spheres of life to the Soviet model. The traditional hospitality of Wielkopolska clashed in a brutal way with the practice of real socialism, which was accompanied by the atmosphere of blatant propaganda, class struggle and everyday life permeated with ideology to an extent unknown before. Each attempt at opposing the new reality was nipped in the bud and brutally repressed.

The sham of the planned socialist economy was especially severe for workers of large Poznań industrial plants. Workers used to pre-war arrangements, good work organisation and fair pay were finding it more and more difficult to support their families. The situation was further exacerbated by the bureaucratic handling of employees and complete incapacitation of trade unions. The workers had basically no chance of handing their postulates to the authorities. The improved living conditions, as announced in the economy development plan based on a Soviet model, turned out to be a myth. The shop supply was disastrous, wages were low, and huge housing problems in the city under reconstruction after war damages were strenuous.

Reasons for the outbreak

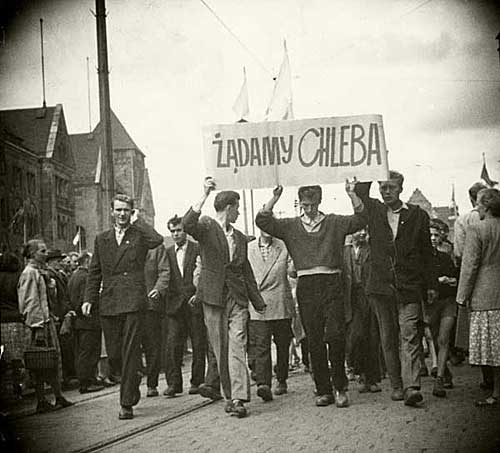

The immediate reason of the outburst of dissatisfaction in Poznań was the issue of irregularities in calculating wages, unrealistic indicators of production growth and efficiency, as well as very poor working conditions in the plants. The place where the feelings of dissatisfaction converged were the former Hipolit Cegielski Poznań factories, renamed after the war to J. Stalin Poznań (ZISPO) factories. The staff of Cegielski had been since 1995 notifying their dissatisfaction with the irregularities in calculating taxes and wages. Workers also complained at bad work organisation. In the face of the fact that the management was unable to meet the workers' demands, representatives of ZISPO staff tried to contact relevant ministries and party authorities. They sent petitions, letters and delegations. The last one went to Warsaw on 26th June 1956 in order to present staff demands. Other plants in Poznań observed with great interest this active approach of HCP staff. The atmosphere was very tense. There were many guests from both Poland and abroad in the city at that time because the city was hosting Poznań International Fair. On the night of 26th June a delegation of workers came back to Poznań, confident that some of their postulates had been positively considered. The next morning, the minister of Machine Industry arrived at the factory and withdrew some of the Warsaw agreements with workers during a mass meeting. In such tense situation, the morning of 28th June witnessed workers' riots in Poznań....The diary of events: www.city.poznan.pl/mim/strony/czerwiec56/pages.html?co=list&id=3043&ch=3060&instance=1017&lang=en&lhs=czerwiec56The giant Cegielski factory, it produced everything, among others ship engines. Most protesters came from it. www.poznan.pl/mim/public/czerwiec56/pictures.html?co=show2&id=8977&instance=1017&parent=4584&lang=enWorkers in the streets. They had enough and wanted to show it to their communist authorities. That was the only way to be noticed and heard.   The demonstrators were carrying Polish national flags and banners: "We demand bread." They shouted: "Down with dictatorship," "Freedom" "We want a catholic, not bolshevik Poland,"    About 100.000 people assembled in the main square of Poznan. All main factories in the city went out.   ![]() www.poznan.pl/czerwiec56/presentation/foto/09.jpg www.poznan.pl/czerwiec56/presentation/foto/09.jpg[/img]   ![]() www.poznan.pl/czerwiec56/presentation/foto/13.jpg www.poznan.pl/czerwiec56/presentation/foto/13.jpg[/img]   Apartment for rent - graffitti on a party building   We demand bread!   It is incredible to see all those people marching against their communist rulers. As if there weren`t secret police, political prisons, Gulag camps, propaganda, repression, censorship. Those people protested because communists had been getting their backs up too long. |

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Mar 22, 2008 8:35:07 GMT 1

|

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Mar 22, 2008 8:43:03 GMT 1

|

|

|

|

Post by franciszek on Mar 22, 2008 20:58:23 GMT 1

These photos are heart breaking i never knew this went on i will show my friends these and tell people about this, more and more Poles come to our town now to work (which to me is great )and more English people get curious.This is no joke but i was asked by a neighbor if Poland was a country i was quite shocked so i educated her and she was amazed at the photos as i am .My father would often say"never trust a Russian" as a boy i did not know what he meant as a man iam now learning.

|

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Mar 23, 2008 9:13:13 GMT 1

These photos are heart breaking i never knew this went on Frank, this thread will continue and you will see more things that Poles experienced in communism. Some of them more drastic than that. It was a normal procedure for communists to shoot at those who disagreed with them. Despite all claims that communism was a better and friendlier system for people, it wasn`t. It was totalitarian and oppressive. Aren`t you dissatisfied that Polish emigrants compete with you in the job market? Many British workers are angry at Poles.... She thought that we are still a part of the Soviet Union. Well, there are ignorant people everywhere. Even in Poland, I suppose many Poles would have a problem saying if Scotland or Wales are independent states or not. Your father lived through the war which was started by Nazi Germans with full support form Soviet Russians. It was a natural reaction for him and others who saw all the horror to distrust Germans and Russians. However, today, Poles prefer to not think so much about the war. Newer generations are open to any nationality, and there is no bias based on war memories. Only the most nationalistic Poles still warn about German or Russian danger, but they are not very popular in the society. I have nothing against Russians, I consider them nice people, quite similar to us, it has been proven by research that Poles and Russians share 50% of their genes, it means something. Russians were also repressed by communism, they paid their price of blood. I distrust those Russians who believe in Great Russia and would like to develop it into an Empire again, with satellite states around or under control. Most Russian politicians are such - I agree with you they they cannot be trusted. Average Russians are OK. PS. The troops which suppressed Poznan protests were purely Polish. They had a Soviet commander of Polish origin, though. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stanislav_PoplavskyA quiz about Poznań 1956 What did workers repeat while marching through the streets? a/ Don`t tread on lawns. b/ Everybody must have a red and white flag c/ Down with communism. d/ Put on your overalls for us to know that you aren`t communist agents. A is a correct answer: Don`t tread on Lawns. |

|

|

|

Post by franciszek on Mar 23, 2008 12:05:58 GMT 1

I have no problems with poles working here if they come here to better their family life back home and the UK allows this then the poles can only be commended must be hard to leave your family for months on end.I watched a pro gramme on TV recently called"The Poles are Coming" It was centered around Peterborough it portrayed how hard working and loyal the Poles are . On interviewing local English they claimed they could not get work because of the Poles one was offered a job picking butternut squash he walked away saying he would rather be on benefits even though he said he would do any type of work.Such i s the mentality of British youth today many believe they are owed a living for some reason so if a nation of people arrive to work hard then this is no problem fortunately for me i have a secure job but for others they will have to improve their game plan. It also highlighted Poland's shortage of their own labour how bad is this situation? i would be interested to know

|

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Apr 23, 2008 14:52:01 GMT 1

After June massacre the political and economic crisis in Poland developed. The thaw caused bigger and bigger holes in the stalinist system of government. The political ferment spread not only among the population, but also among party members. They knew the changes were inevitable. The events which were going to take place are called October 1956.

After Bierut's death and June massacre in Poznan a new candidate for the first secretary of KC PZPR was needed. In October Władysław Gomulka, a communist oppressed by other communists before, took part in works of strict party management. He presented his program of the end of political crisis and economic difficulties. On October 19th 1956 Gomulka was chosen the first secretary of the communist party. On the same day Nikita Chruszczow (the leader of the USSR) with commander of armed forces of Warsaw Treaty Organization and generals of Soviet army arrived in Warsaw. Chruszczow did not want to accept any changes in Poland and Gomulka's return to the authority. There were heated dicsussions with shouting, fist shaking etc. However Chruszczow changed his mind because of Gomulka's persuasions, who assured him that the authority would be still in communists' hands, provided that there would be a reform of political administration. Which was more important, he claimed that Poland would not leave the Warsaw Treaty Organization and that the basic principles of policy would not be changed.

Gomulka was supported by society, he became a national hero. People were glad that Poland gained some more independence from the USSR.

In this situation Chruszczow stopped Soviet armies which were ready for an invasion. Some units, stationing in Poland, were actually marching towards Warsaw. Gomulka was a tough negotiator, he threatened Soviet leaders with Polish resistance.

Eventually, new Polish party team was invited to Moscow in order to continue negotiations on political, economic and army issues.

On October 20th Russians came back to Moscow. Gomulka ordered to set free the cardinal Stefan Wyszynski from jail.

The most important thing was a little more independence of Poland in communist block and creation of new relations with the USSR. Besides the dictatorial Stalin's way of governing was dropped. The peasants were allowed to withdraw from the co-operatives. Marshal Rokossowski and lots of other Russian officers serving in the Polish Army were dismissed and left Poland. October 1956 also started the rehabilitation of people who were unjustly persecuted during stalinist system.

The purpose of Gomulka and his team was to continue to build the socialist system in Poland.

From October 1956 Gomulka was moving away from his promises. He knew that at the beginning he could not attack straight away because in this way he would have lost his popularity. Therefore he tried to withdraw gradually, as he was reinforcing his authority.

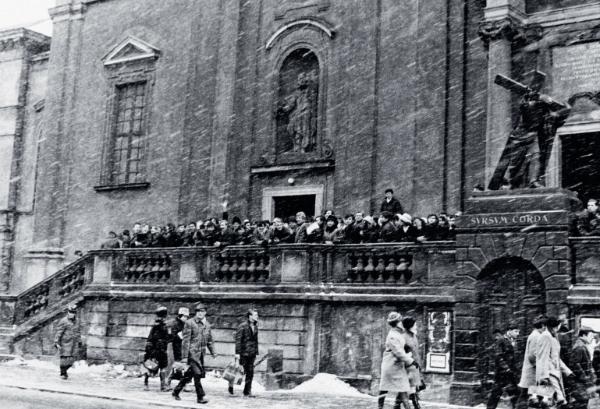

Crowds of people who came to a rally to express their support for Gomulka in his negotiations with the Soviets. Poles hoped that Gomulka was able and willing to strive for independent Poland.   See the film from the meeting Another commentary on events.

On October. 19, 1956, the Polish Central Committee was about to re-elect Gomulka as First Secretary of the Party. It also decided to dismiss the Polish-born Soviet Marshal Konstanty Rokossovsky as Commander-in-Chief of the Polish armed forces. These moves worried the Moscow leaders, for the Warsaw Pact - the Eastern equivalent of NATO - had been signed in 1955, and now the Soviet general who was the C-in-C of the Polish Armed Forces, was being booted out.

On October 19, Khrushchev suddenly arrived by plane in Warsaw with a high ranking delegation made up of Party Politburo Members Anastas I. Mikoyan (1895-1978), a close collaborator of Khrushchev; Foreign Minister V.M. Molotov, and Lazar M. Kaganovich,(1893-1997) along with Defense Minister Marshal Georgii K. Zhukov (1896-1974) , Marshal Aleksy I. Antonov (1896-1962) Warsaw Pact Chief of Staff, and Marshal Ivan S. Konev (1897-1973), First Soviet Deputy Defense Minister and Commander-in-Chief of the Warsaw Pact. Khrushchev had long talks with Gomulka and the Polish Premier, Jozef Cyrankiewicz (1911-1989, pron. Tsirankyeveech).

At the same time, Soviet troops massed on Polish borders in the East and West and Soviet warships stood off the coast. The two Soviet motorized divisions stationed at Legnica, S.W. Poland, began to move toward Warsaw. In this situation, the Polish Army, now under the command of Gen.Marian Spychalski, (1906-1980,a colleague of Gomulka's who had been tried and imprisoned in the purges), seemed ready to resist a Soviet invasion. Also, the workers at Warsaw's Zeran (pron. Zherani) automobile factory took up arms and mounted guard over the new leaders and other party members to prevent their arrest.

No Russian record of the Khrushchev - Gomulka -Cyrankiewicz talks has surfaced to date, but the Polish record indicates that Khrushchev was very belligerent. He attacked Gomulka for the dismissal of Rokossovsky and used a threatening tone throughout, while Gomulka protested against the concentration of Soviet armed forces on Poland’s frontiers.

Nevertheless, Gomulka went on to be elected First Secretary of the UPWP that same day, while the Soviet delegation left Warsaw on the morning of October 20. Khrushchev and his closest advisers weighed the possibility of invading Poland, but decided against it - presumably because it would be easier to get into Poland than to get out of it. In any case, the official communique stated the "debates were held in an atmosphere of Party-like and friendly sincerity," also that a delegation of the Polish Politburo would soon travel to Moscow to discuss the strengthening of political and economic cooperation between the two countries. * Indeed, Gomulka soon traveled to Moscow, where he managed to obtain the Soviet cancellation of Polish debts, promises of economic aid, and an agreement of the repatriation of Polish citizens still remaining in the USSR after World War II.

It seems that the Chinese Foreign Minister, Zhu en-Lai (1898-1976), advised Khrushchev to make concessions to the Poles. If true, perhaps this was because the Chinese leader Mao ze-Dong was furious with Khrushchev for his anti-Stalin speech and wanted to see a loosening of Soviet domination over E. Europe.

Whatever the case may be, on October 20, Gomulka made a long speech to the Polish party’s Central Committee, severely criticizing the economic mistakes of the last few years and the "personality cult" (Bierut).

Four days later, on October 24, he made a public speech to some 300,000 people gathered in the square outside the Palace of Culture, Warsaw, which was broadcast all over Poland. Here he also criticized past mistakes and promised reforms. In particular, he told the peasants who had been forced into collective farms that they could leave if they so wished, and they did so in droves. From this site web.ku.edu/~eceurope/hist557/lect17.htm |

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Apr 23, 2008 20:21:35 GMT 1

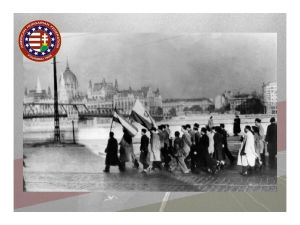

web.ku.edu/~eceurope/hist557/lect17.htmAt this time, Gomulka enjoyed widespread popular support, for most Poles saw him as a Polish patriot who would put an end to the horrors of the past and pursue a more independent policy. Also, it looked as if Gomulka had faced down Khrushchev, who flew off to Moscow with his retinue. These events in Poland sparked the Hungarian Revolution.

On October 22, when it looked as if Gomulka had faced down Khrushchev in Poland, mass demonstrations of solidarity with Poland took place in Budapest. The students of the Budapest Engineering and Construction University came out with a list of 16 demands. These included the withdrawal of all Soviet troops from Hungary; the reorganization of the government under Imre Nagy’s leadership; free elections for a new multi-party national assembly; reform of workers’ production norms and of the existing agricultural system; the rehabilitation of all victims of past injustices; the taking down of the Stalin statue in Budapest; and full freedom of speech and press. Finally, they expressed their solidarity with the workers and young people of Poland and Warsaw, "who were participating in the movement for Polish independence," and announced that a parliament of young people would be held in Budapest on October 27, which would work with the participation of youth delegates from all over the country. The Soviet ambassador in Budapest, Yuri V. Andropov,(1914-1984) immediately reported the 16 points to Moscow.The Budapest students announced a demonstration of sympathy with Poland in front of the Polish Embassy at 2.30 p.m. The Ministry of the Interior broadcast a prohibition of this meeting at 12.53, but rescinded it at 2.23 p.m.. Just before that, the demonstrations gathered at the statue of the national poet of Hungary, Sandor Petofi. They recited verses in which he called on the Hungarian people to stand up and refuse to be slaves. The demonstrators then went to the statue of Jozef Bem (1794-1850), a Polish general who had led Hungarian armies against the Russians in 1849, and expressed their sympathy for Poland. Hungarian students carry the Polish national emblem they made and Polish flags.   www.americanhungarianfederation.org/news_1956-2013_ShepherdCenter.html www.americanhungarianfederation.org/news_1956-2013_ShepherdCenter.html The rally at Bem monument in Budapest, a Polish general who led Hungarians against Russian invaders in 19 centuries.  Hungarian recollections: George Gömöri (student of the Polish Philology Department of the University in Budapest): It was generally known that something extraordinary was happening in Poland, but nobody knew exactly what this meant. A day earlier the party’s organ “Szabad Nep” published the text of Gomułka’s speech but not everyone had a chance to read it and even those who had read the text were confused. What happened in Poland? So I went out in a hurry and I soon saw T. and his friends. I greeted them and before I managed to open my mouth to ask what had actually happened, someone said: “Haven’t you heard? The Soviet troops have surrounded Warsaw. […] We knew only that the Poles were demanding greater freedom and greater national independence, which was the reason why they had elected Gomułka. The Russians were trying to prevent these changes. We had to do something. […] After a short discussion we decided to mobilize our friends and acquaintances to stage a peaceful demonstration to support the beleaguered Poles.

www.1956.pl/7,40.html We all know how the Budapest Revolution ended. Soviet tank units crushed it without mercy. Hungarian leaders were caught and hanged, 200.000 people fled to Austria. Communism prevailed once again.  Hungarian revolutionaries

|

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Apr 23, 2008 20:48:30 GMT 1

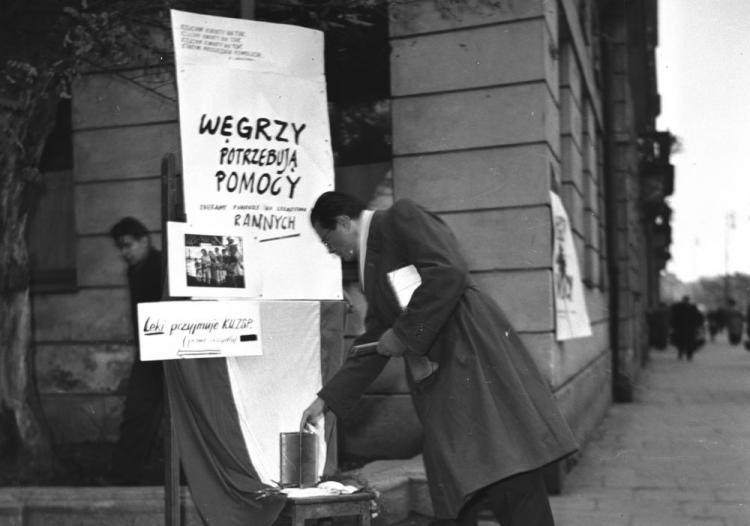

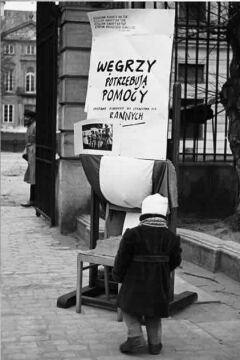

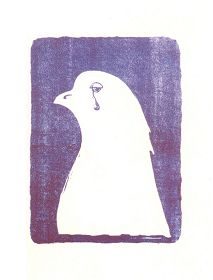

Poles have always felt close ties with Hungarians. Hungarian princes were Polish kings, Polish generals fought for Hungarian freedom. Poles who were lucky to avoid the Soviet intervention in October 1956 felt pity for Hungarians who stood up and were crushed by Soviet armies. The support for Hungarian revolution was expressed at rallies in streets and factories, as well as massive collection of supplies of medicine, blood and food to be sent to Hungary in train transports. Poles mass-demonstrated in their country to show their support for the revolution. "Hands off Hungary!!!" The aid`s worth was estimated at 2 million dollars, a very high sum for Poles at the time. Poles donated a lot. However, Polish engine drivers and customs officers had to battle Czechoslovakian border services which tried to stop the transports. A popular saying at the hot time: Hungarians behaved like Poles, Poles behaved like Czechs, Czechs behaved like swine. It means: Hungarians behaved like Poles, because they fought a romantic battle with no chances of winning, Poles behaved like the Czech because they succeeded to get what they wanted from Soviets avoiding a typical Polish blodshed, and the Czech behaved like swine because they didn`t allow trains with humanitarian aid to go to Hungary from Poland. The Hungarian rising was welcomed by Poles with great enthusiasm. Polish students who studied at universities in Budapest joined the rebels. Some of them were given medals during various anniversaries recently. Polish solidarity with Hungarians: Student guards in front of a Hungarian flag with words: Tribute to Hungarian nation.  Poles gave blood for Hungarians  Loading blood onto transports   Humanitarian aid transports   Rally in support of Hungarian revolution, you can see Hungarian flags and banners     Hands off Hungary!  Polish papers encouraged to collect supplies for Hungarians  A poster advertising a poetic and musical event to honour Hungarians and collect funds for aid.   In 1970s Polish opposition hung such banners: We remember Hungary 1956  The most moving symbol of Polish attitude to Hungarian revolution was a poster I saw once but can`t find it on the Net. It presented a pidgeon shedding a tear. Very moving. I will try to find it. Here it is  |

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on May 1, 2008 20:10:07 GMT 1

1968 was a year of turmoil and trouble. According to Chinese Zodiac, it was the year of the Monkey. Whenever Monkey sign rules, there is a common need for change. Poles soon became disenchanted with their first secretary, Władysław Gomułka. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/W%C5%82adys%C5%82aw_Gomu%C5%82ka He turned out to be a dogmatic communist despite his attempts to preserve certain independence from the Soviet Union. Intellectuals complained about the censorship and limited provision of paper for book publications. Average people complained about hard conditions of life, understocked stores and low salaries. In 1968, 12 years after the previous crisis, students and intellectuals rose and spoke out their grievances. The communist regime cracked on them with its usual brutality. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1968_Polish_political_crisisThe Polish 1968 political crisis (also known in Polish as 'March 1968' or 'March events', Polish: Marzec 1968 or wydarzenia marcowe) describes the major student and intellectual protests against the communist government of the People's Republic of Poland, their repression by the security servies, and the concurrent Soviet anti-Zionist reaction. The protests coincided with the events of Prague spring in neighboring Czechoslovakia.

In January, the communist government banned the performance of a play by Adam Mickiewicz, (Dziady, written in 1824) and directed by Kazimierz Dejmek at the Polish Theatre in Warsaw, on the grounds that it contained Russophobic and "anti-socialist" references. The play had been performed 14 times, the last on January 30. Dejmek was expelled from the Communist Party and later fired from the National Theatre.

upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/9/90/Dziady_1968.jpg

The Warsaw Writers' Union condemned the ban on March 2, followed by the Actors' Union. A crowd of some 1,500 students protesting at Warsaw University on March 8 was met by attacks. Within four days, protests spread to Kraków, Lublin, Gliwice, Wrocław, Gdańsk, Poznań, and Łódź. Bands of Communist party "worker-squads" attacked the students, followed by police in Warsaw and Lublin. Mass student strikes took place in Wrocław on March 14-16, Kraków on March 14-20, and Opole. A call for a general strike was issued from Warsaw on March 13. A hardline speech by Władysław Gomułka on March 19 cut off the possibility of negotiation. Further student protests, strikes and occupations were met with the mass expulsion of thousands of participants. National coordination by the students was attempted through a March 25 meeting in Wrocław; most of its attendees were jailed by the end of April. At least 2,725 people were arrested for participating. According to internal government reports, the suppression was generally effective, although students were able to disrupt May Day ceremonies is Wroclaw.

It all started with Dziady, a patriotic play by the greatest Polish poet, Mickiewicz. marzec1968.pl/portal/m68/797/6959/Dziady.htmlStudents gather in front of universities to protest      ![]() ![]()    The police attacks         Running away...    from the brutal police    Churches where students hid were sometimes tear gassed    The map of protests. All cities with academic life protested.  Students` banner: Truncheons can`t kill the truth.  Students on strike thanked Warsawians for their aid: food and blankets.  Workers didn`t support students. Banner reads: Writers - return to the pen, students - return to studying, Zionists to Israel.  Students march to demand the release of their imprisoned mates.  Some professors defended their students and went to court to testify for those accused. |

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on May 1, 2008 21:02:40 GMT 1

Pictures from 1968 students` protests

|

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on May 7, 2008 15:03:20 GMT 1

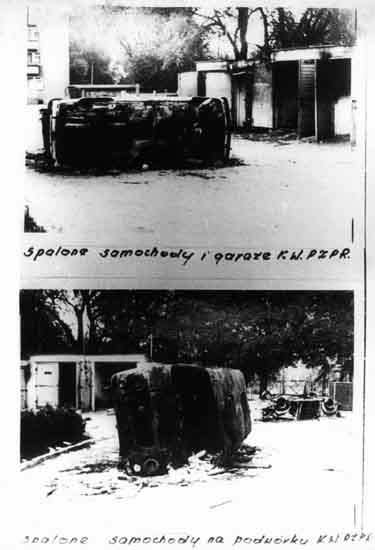

The next painful event which became another date on the list of communist crimes against the Polish nation was December 1970. In all major cities of the Polish coast, the communist police and army shot at workers who demanded lower prices of food. The greatest tragedy happened in Gdynia, where tanks and helicopters were used to massacre the peaceful crowd of workers coming to work. Officially communists admitted to only 46 dead, but witnesses and doctors who looked after shot people suggested hundreds of victims. The protests were sparked by a sudden increase of prices of food and articles of daily use. Władysław Gomułka's temporary political success could not mask the economic crisis into which the People's Republic of Poland was drifting. Although the system of fixed, artificially low food prices kept urban discontent under control, it caused stagnation in agriculture and made more expensive food imports necessary. This was unsustainable, and in December 1970 the regime suddenly announced massive increases in the prices of basic foodstuffs. On Saturday, December 12, 1970, Warsaw radio announced price increases for food and other basics amounting in some cases to 60%. At the same time, the "thirteenth month" salary or Christmas bonus for workers in particularly dangerous industries such as ship building, steel mills and coal mines, was cancelled. The timing of this move, just before Christmas, without any preparation of public opinion, was very bad psychology on the part of the government. It is possible that the price rises were imposed on Gomułka by his enemies in the Party leadership who planned to manoeuvre him out of power. The rises were a fatal miscalculation, for they proved to be a major shock to the society and turned the urban workers against the regime. Demonstrations against the price rises broke out in the northern Baltic coastal cities of Gdańsk, Gdynia, Elbląg and Szczecin. On December 15, 3,000 workers from the Lenin Shipyard, Gdansk, along with workers from other state enterprises in the city, marched to Party Headquarters to protest. A police officer lost his nerve and shot one of the workers; the worker's colleagues set fire to the building, and the staff had to be evacuated from the roof by helicopter. The workers began sit-ins at the Gdansk and Gdynia shipyards. Nevertheless, the local party leaders persuaded them to go back to work by promising to forward their demands to Warsaw and to support them. However, on December 16, when commuter workers began arriving at the Paris Commune shipyard railway station in nearby Gdynia, they were attacked by riot police. Those who came after them, could not leave the station without being shot, but more kept arriving so they spilled outside - and were shot. This was the result of Gomulka's decision that there was a "counter-revolution" in Gdansk, that had to be put down by force. Troops were sent in. They were told that they were going to defend Gdansk against a German invasion (!). Now strike committees were set up in the shipyards at Gdansk, Gdynia and Szczecin. What is more, at Szczecin, the workers of several enterprizes, led by those of the Warski (pron.Varskee) shipyard, formed an interfactory strike committee. This committee made some demands, including the establishment of a non-party Trade Union leadership. Gomułka ordered the army to fire on the workers as they protested in the street. Another leader, Stanisław Kociołek, appealed to the workers to return to work. But in Gdynia the soldiers had orders to stop workers returning to work, and they fired into the crowd of workers emerging from their trains on December 17: hundreds of workers were killed or wounded. The protest movement then spread to other cities, leading to strikes and occupations. All those who perished were buried overnight, with only the closest relatives present, in order to avoid spreading the riots. The Party leadership met in Warsaw and decided that a full-scale working-class revolt was inevitable unless drastic steps were taken. With the consent of Leonid Brezhnev in Moscow, Gomułka, Kliszko and other leaders were forced to resign: Edward Gierek was drafted as the new leader. The price rises were reversed, wage rises announced, and sweeping economic and political changes were promised. Gierek went to Gdańsk and met the workers, apologised for the mistakes of the past, promised a political renewal and said that as a worker himself he would now govern for the people. Szczecin - December 1970- dockyard workers march towards KW PZPR party headquarters.  The protest in Szczecin’ s shipyard was growing gradually, but unrelentingly. At last, on Thursday morning 17 December 1970, desperate dockyard workers left their place of work and marched towards city center and magnificent edifice of Provincial Party Committee. Riots which were started there ended up with setting fire to the building. After that, the crowd marched to nearby provincial police office, trying to take it by storm. In a short time the situation was dramatic. Bullets reached and killed first participants of demonstration. A few of them were wounded. Policemen and agents of SB were shooting wild. Innocent people died, often - in their own flats where they stayed because of imposed curfew. Real number of victims is still unknown... Riots which started near the police office and KW PZPR building soon turned into an open and bloody fight  Szczecin - demonstrating dockyard workers first protest, then set fire to edifice KWPZPR on Soldier's Square The soldiers in armoured carriers didn`t react at first.    The workers surrounded armoured vehicles and made soldiers leave.  |

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on May 7, 2008 15:32:23 GMT 1

|

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Jul 1, 2008 20:01:23 GMT 1

Polish court OKs trial for Gen. Jaruzelski

By MONIKA SCISLOWSKA

6/30/08

WARSAW, Poland (AP) — An appeals court on Monday cleared the way for Gen. Wojciech Jaruzelski, Poland's last communist leader, to be tried for imposing martial law in 1981 as part of a brutal crackdown on pro-democracy activists.

The ruling overturned a lower court's decision demanding that prosecutors from the state's Institute of National Remembrance gather more evidence before the case could go to trial.

It also means that Jaruzelski, 84, and eight other former communist officials — some of whom are in poor health — will be tried for the role in the crackdown, which put tanks on Polish streets and thousands of pro-democracy activists in internment camps. Some 100 Poles died during the clampdown.

No date has been set for the trial, but court spokesman Wojciech Malek said it could be as soon as September or October.

Jaruzelski did not immediately comment on the decision but has indicated before he would welcome any trial so he could can explain the motives and circumstances behind his decision.

Jaruzelski has long defended his decision to impose martial law as the "lesser evil." He has argued that it was the only way to prevent a Soviet invasion to crack down on the pro-democracy Solidarity labor union movement itself.

The retired general spent a few weeks in a hospital in February with heart problems and pneumonia before undergoing a minor procedure to stabilize his heart in March.

Prosecutors charged Jaruzelski and the others in March 2006 with violating the constitution and with leading an "organized criminal group of a military nature having as its goal the carrying out of crimes that consisted of the deprivation of freedom through internment."

If convicted, Jaruzelski could face up to 10 years in prison, and the others shorter terms.

In May, a Warsaw court ruled that evidence gathered is incomplete and ordered the prosecutors to seek testimony from foreign officials such as former British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and former Secretary of State Alexander Haig — to determine the international context of the communist leadership's decision to impose the crackdown.

|

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Jul 19, 2008 20:25:58 GMT 1

The next mass protest against communist authorities took place in 1976, again the spark which ignited emotions were prices. June 1976 is the name of a series of protests and demonstrations in People's Republic of Poland. The protests took place after Prime Minister Piotr Jaroszewicz revealed the plan for an increase in the price of many basic commodities, particularly foodstuffs (butter by 33%, meat by 70%, and sugar by 100%). Prices in Poland were at that time fixed, and controlled by the government, which was falling into increasing debt. The protests started on 24 June and lasted till 30 June, the largest violent demonstrations and looting taking place in Płock and particularly Radom. The protests were quelled by the government, but the plan for the price increase was shelved; Polish leader Edward Gierek backed down and dismissed Prime Minister Jaroszewicz. This left the government looking both economically foolish and politically weak, a very dangerous combination. The 1976 disturbances and the subsequent arrests and dismissals of militant workers brought the workers and the intellectual opposition to the regime back into contact. In the aftermath, the Komitet Obrony Robotników opposition organization was created.en.wikipedia.org/wiki/June_1976_protests

The Radom Anniversary

Occurring on 24 June 1976, the Radom riots were related to the nationwide workers' protest against the government decision to implement a previously unannounced increase in the prices of food and meat. They took the form of a spontaneous demonstration by workers on the city streets, a demonstration during which some public office buildings were severely damaged and many shops were looted. A similar demonstration also took place in a large tractor factory in Ursus, near Warsaw. No counterreaction by military units was organized that time in either place, although police intervened to break up the demonstration in Radom and the authorities subsequently arrested and prosecuted many hundreds of protesters.

In contrast to the Poznan rebellion of 1956, however, the workers' protest of 1976 ended with major success. The government, apparently concerned about the possibility that the workers' agitation could persist and mindful that an earlier proletarian protest in December 1970 had led to a drastic change in leadership, decided to reverse its decision on prices. On the evening of 25 June 1976, less than 24 hours after the original announcement of the increases, the food prices were rescinded.

Viewed in retrospect, the 1976 workers' protest against official economic policy was a turning point both in the process of government decision-making and in the evolution of the social movement of self-assertion. 9 The government's operations, especially in the area of economic policy-making, came to an almost complete standstill. Although economic conditions in the country continued to deteriorate, no comprehensive strategy of action to combat the difficulties was introduced. Instead, the running of economic policy became a succession of ad hoc moves, with frequent changes of course or contradictory implications. The main preoccupation of the leadership was with finding expedient ways to prevent a further decline, rather than introducing innovation. The net effect of that attitude, however, was growing public disillusionment with the government's performance, operational chaos, and a mounting feeling of uncertainty as to the future development of the country.

The political and social repercussions of the protest were equally significant. More than anything else, the success of the workers in preventing the implementation of a government decision in 1976, particularly when coupled with a similar success in 1971, exposed the vulnerability of the political system to social pressures. This element alone greatly enhanced the resolve of both the workers and other social groups to demand access to participation in the process of politics. Needless to say, this development adversely influenced the effectiveness of the government and further undermined its authority.

More specifically, following a series of repressive measures against selected groups of workers from Radom and Ursus, where incidents of limited violence had taken place, there was widespread public criticism of the authorities' punitive action. This led to the establishment, in September 1976, of the Committee for the Defense of the Workers (KOR). Set up by a small group of prominent intellectuals, the committee's main task was to provide legal and financial help to the families of imprisoned workers and to campaign for their release. The emergence of KOR and the subsequent expansion of its activities to other areas of Poland's public life prompted the establishment of other dissident organizations and groups. Finally, in early 1978, the first units of the free trade union movement were established by workers in mining and shipping centers. Their aim was to serve as the nucleus of a future independent syndicalist movement that would be autonomous of the existing party-dominated institutions. The current Solidarity labor organization, which was set up as the result of workers' strikes in July-August 1980, has grown from the foundations provided by the free trade union movement.libcom.org/library/poznan-1956-radom-1976The party headquarters in Radom is burning...   People crowd on the strategic railway which connected Moscow with Russian troops in Eastern Germany.  Party bosses` cars were burnt too.  The answer was typical www.zomoza.kgb.pl/galeria/1973_1982/czerwiec_1976/radom_76_tyraliera_zomo.jpg Staging of Radom events  |

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Jul 19, 2008 21:01:52 GMT 1

From this site web.ku.edu/~eceurope/hist557/lect18a.htmIn 1976 protests broke out all over the country, especially in the city of Radom and the tractor factory "Ursus," just outside of Warsaw, but they were brutally put down. However, this time the workers and the intelligentsia came together and a new dissident movement was born. This dissident movement was supported by the Catholic Church, which, in December 1970, had already come out in support of civic and human rights. At that time, Cardinal Wyszynski had demanded freedom of conscience, freedom of religious belief, free cultural activity, the right to truth and freedom of speech. He also supported a group of intellectuals who criticized the draft of the new Polish Constitution in March 1976 for making respect of civil rights conditional on obedience to the party, and on recognizing Poland’s subordination to the USSR. At this time, Wyszynski also proposed the establishment of free trade unions, an independent judiciary and civil service, and free elections to parliament Furthermore, he spoke for the economic rights of private farmers, demanded respect for the indispensable civil rights of all Poles, and said the Constitution should not contain anything that could limit the sovereignty of the Polish state. No wonder that Wyszynski was seen as the spokesman of the Polish nation.* Thus, the role of the Catholic Church was very important in paving the way for the development of a strong dissident movement in Poland. *[See: Bogdan Szajkowski, Next to God...Poland. Politics and Religion in Contemporary Poland, New York, 1983, pp. 31-33, 40-41; in abbreviated form: Sabrina P. Ramet, NIHIL OBSTAT. Religion, Politics and Social Change in East Central Europe and Russia, Durham N.C.and London, 1998, p.101]. The Committee for the Defense of Polish Workers -KOR As mentioned earlier, the workers’ revolt against the price hike of June 1976 was brutally put down - even though the government rescinded the price increase to prevent further unrest. The brutalityused to repress the workers of the Ursus Tractor Factory near Warsaw and in the town of Radom -- they were beaten by the police, and some died -- outraged public opinion. A group of intellectuals organized the Komitet Obrony Robotnikow - KOR (the Committee for the Defense of Polish Workers) in late summer-early fall 1976. In 1978, it changed its name to Komitet Samoobrony Spolecznej, KSS KOR (= Committee for Social Self- Defense). Two of its best known members were Jacek Kuron [pron. Kooron] and Adam Michnik (pron. Meekhneek) both trained historians and former communists. Others included the literary critic Jan Jozef Lipski (pron. Yan Yoozef Leepskee), a dissident since 1955, and the historian Bronislaw Gieremek,[pron. Brohneeswav Gyerehmehk] who had resigned from the party in 1968. The leadership also included the well known actress, Halina Mikolajska (pron. Haaleenah Meekowayskah). KOR’s original goal was to help the workers. It collected money to aid workers’ families deprived of their breadwinners and to pay defense costs for trials. KOR published its first underground bulletin in September, but it adopted the policy of open activism. This meant that KOR members claimed the rights of freedom of speech, association, and publication on the basis of existing rights in the Polish Constitution, the Helsinki Agreements of August 1975 (which specifically safeguarded human rights), and international labor agreements - all signed by the Polish and other communist governments. Thus, while publications were printed underground without government permission, the authors signed their names, daring the authorities to come after them. KOR was the first organization to adopt this policy in a Soviet bloc state. It provided a model for the Czech Charter 77 dissident group formed in Czechoslovakia in 1977. Similar organizations, but leaning toward the center or the right, followed. The Ruch Obrony Praw Czlowieka i Obywatela -ROPCIO (Movement for the Defense of the Rights of Man and Citizen) represented moderately reformist and right-wing intelligentsia, while the Konfederacja Polski Niepodleglej -KPN (Confederation for an Independent Poland) was a right wing organization. KPN members such as Antoni Macierewicz (Aantonee Matsierevich)and Jan Olszewski (Yan Olshveskee) were so adamantly anti-communist that they came to oppose the leaders of KOR because some had been communists in the past. (This enmity was to continue into the post-communist period). An underground educational organization was established in 1978. This was the Towarzystwo Kursow Naukowych -TKN (Association for Scholarly Courses), made up of university professors, junior faculty, graduate students, lawyers, writers, and artists. They organized seminars on subjects not taught or politically distorted at the universities such as recent Polish history, literature, philosophy, sociology, and economics. The seminars were held in private apartments, so they were reminiscent of the "Flying Universities," which existed in Warsaw under Russian rule in the period 1890-1914, also the underground university education that existed under the German occupation in World War II. The police harassed the professors, students, and apartment owners, but for the most part the first two could be threatened with the loss of jobs or stipends, or held under arrest for 48hrs, while the last were fined. Despite the harassment, the TKN flourished, and the church allowed it as well as other dissident organizations, to use church buildings. Also, lawyers went out into the countryside to advise private farmers about their rights in legal disputes with the authorities. KOR and Mloda Polska (Young Poland, a right wing organization) cooperated in establishing the Free Baltic Trade Union in Gdansk, February 1978, where future worker leaders such as Lech Walesa, Anna Walentynowicz (Valentynovich), Andrzej and Joanna Gwiazda (Gvyazdah), and Bogdan Lis (Lees), obtained instruction and advice on organizing political activities. Another Free Trade Union was organized in Upper Silesia. KOR also published an underground paper for workers: Robotnik (The Worker). It had the same name as the socialist paper published for workers by Jozef Pilsudski before the First World War.  J.J.Lipski, A.Michnik, H.Mikolajska, 1978 |

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Jul 19, 2008 21:11:43 GMT 1

web.ku.edu/~eceurope/hist557/lect18a.htmKOR, ROPCIO, KPN, and Mloda Polska (Young Poland) inspired and helped organize annual celebrations of May 3, in honor of the Polish Constitution of May 3, 1791. [ See Lec.Notes no. 4. May 3 had been a public holiday in interwar Poland]. Indeed, Lech Walesa once drove around Gdansk handing out copies of the Constitution as part of the local protest movement. They organized special masses on May 3 and also November 11 - celebrated as independence day in interwar Poland. [On Nov. 11, 1918 -- Armistice on the Western Front -- Pilsudski cleared Warsaw of German troops, who were allowed to go home. Later, November 11 became the Polish Indepndence Day] A demonstration of illegal KPN to celebrate the anniversary of WW2 on 1 September 1979.  Sometimes demonstrations followed mass in church, and people were attacked by the police. There were also special masses on September 17, in memory of the Soviet invasion of eastern Poland in 1939. Indeed, in September 1979, there were slogans on the walls of some Warsaw buildings that read: "Remember September 17!" On November 11 of that year - independence day in prewar Poland - police charged a procession of people walking from a Warsaw church to the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. In fact, national symbols were increasingly fused with opposition to the government, which now included workers. The latter demanded a monument in memory of the workers killed at Gdansk on December 16 1970. Walesa tried to lay a wreath on the site of workers killed there on each anniversary after 1976, but the police usually confiscated it. On one occasion, however, the policemen delivered the wreath to St.Bridget’s Church, whose pastor, Father Jankowski, supported the workers. Finally, a large underground press developed in the period 1976-80. This too had precedents in the 1890-1914 and 1939-45 periods of Polish history. In the early days, dissident printers requested technical advice from Home Army veterans of World War II, but they soon acquired xerox and printing machines smuggled in from the West. In 1979-80, about 400 different publications were printed by underground presses, including books published by Miroslaw Chojecki (pron. Meeroswaf Khoyetskee) in his publishing enterprise Nova. He even displayed them at the annual Warsaw book fair, where the police did not intervene because western booksellers were present. Polish authorities acted under some constraints when harassing the rapidly growing dissident movement. Too much repression might lead to public protest and unrest; it also risked antagonizing both the church and the U.S. government - which was shipping surplus food products to Poland in exchange for Polish currency scholarships for U.S. students in Poland and Polish books for U.S. libraries. (Public Law 480). Furthermore, one of President Jimmy Carter’s key policies was support of human rights, which was a boost for Polish dissidents. He visited Poland in December 1977, the third U.S. President to do so after Richard Nixon (1972) and Gerald Ford (1975). When Carter landed at Warsaw airport, the official U.S. translator , who was more familiar with Russian than Polish, translated Carter’s phrase on the Polish "love of freedom, " as "lust for freedom," to the great amusement of the Polish public. U.S. TV coverage of the presidential visit included an underground seminar being held in a Warsaw apartment. The Election of the Polish Pope and his visit to Poland in June 1979.. On October 16, 1978, Cardinal Karol Wojtyla, Archbishop of Krakow, was elected Pope by the College of Cardinals in Rome and took the name of John Paul II. He was the first non-Italian pope to be elected since the Dutchman Adrian VI, who was briefly Pope in 1522-23. Poland went wild with joy. People stood in line to ring the church bells. The government hesitated at first, but then hailed the Pope as "a great son of Poland,"and allowed the ceremony to be shown on Polish TV. Rumor had it that Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev phoned Gierek and asked angrily why he did not prevent Wojtyla's election; after all, Wojtyla was a Polish subject! He must have been even more worried on hearing of the Pope’s plan to visit Poland in 1979. Indeed, John Paul’s visit to Poland in June 1979 had a tremendous impact on the country. He was seen and heard by millions of people - though Polish TV carefully omitted showing the crowds which could be seen on western TV. Some 200,000 people attended his open air mass in Warsaw and about 1,000,000 came to hear him on the fields below the monastery of Jasna Gora (pron. Yasnah Goorah) at Czestochowa [pron. Chenstokhovah]. Over a million heard him in and around Krakow. John Paul II spoke about the people’s right to "have God in their lives," and the "right to freedom." Order was kept everywhere by Catholic laymen and the police were hardly visible. People realized that strength lay in numbers and this broke the barrier of fear. Thus, the Pope’s visit in June 1979 was an important prelude to the birth of Solidarity in August 1980.       As Adam Michnik wrote twenty-four years later: "For the people of Poland, John Paul II, by making human rights the central subject of his teaching, will for ever be the man who gave us courage and hope, who restored our historical identity. (The Independent, London, Nov. 17, 2003)

|

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Aug 24, 2008 23:29:24 GMT 1

Political Jokes under Communism

Polish Radio

06.08.2008

The Institute of National Remembrance, investigating Nazi and

communist era crimes, has published a bulletin on how Poles laughed at and ridiculed the hated communist rule and Soviet domination.

Krystyna Kolosowska reports.

What is the biggest success of Soviet medicine? That Lenin is

forever alive. This is an example of a typical political joke from

that time. Joke telling thrived in communist Poland, which was often

called the merriest barrack in the Soviet bloc. But, as Krzysztof

Bobinski, from the Poland –European Union magazine, points out it

was often hardly a laughing matter. What would happen if a secret

police officer overheard us telling such jokes?

`It depends on the year. If this joke was told in 1954 or 1951, then

one or the other of us, or both would probably go to prison. One

would go to prison for telling the joke, the other for listening to

the joke and not informing police authorities that such a joke had

been told.'

Professor Jan Zaryn, head of the Public Education Office at the

National Remembrance Institute, says political jokes were a popular

form of public protest against absurd realities in communist Poland.

`Jokes had a therapeutic impact as well. They had typical subjects –

like communist party leaders both in Warsaw and in Moscow. But there were also objects, such as sausage or alcohol or rather their

absence.'

Jan Pietrzak, who led and himself appeared in hugely popular

satirical cabaret shows, recalls that the constant consumer goods

and food scarcity was frequently the subject of political jokes:

`People born before the 2nd world war, like me, recalled how before the war you could see shops with the sign saying "butcher". Inside there was meat. During communist rule the sign on such shops read – "meat", inside there was only the butcher.'

Cabarets, like the one run by Jan Pietrzak, thrived after September

1956 when Poland experienced a political thaw, a relaxation of some tough rules of the communist system. Why did the leaders let them exist? Krzysztof Bobinski has this explanation:

`The cabaret in a country like Poland, which was then seen as the

merriest barrack in the Soviet bloc, was seen by the authorities as

a kind of a safety valve for emotion. They really were a way of

allowing people to let off steam but there weren't very many of them and they were controlled.'

Telling jokes at that time could be risky, as Krzysztof Bobinski

said at the start. A man was sentenced to two years in prison for a

joke on a portrait of the Soviet leader Stalin. The bulletin

published by the Institute of National Remembrance recalls many such more or less dangerous jokes. The snag is that many may not be comprehensible to younger people today, who do not remember the realities of the communist era.

|

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Sept 12, 2008 22:03:41 GMT 1

Poland's former leader on trial

By Adam Easton

BBC News, Warsaw

Gen Jaruzelski remains a highly controversial figure in Poland

Poland's last communist leader, General Wojciech Jaruzelski, has gone on trial accused of committing a crime by imposing martial law in 1981.

Eight other former officials will also be tried for the clampdown against the opposition Solidarity movement, during which dozens of people were killed.

Gen Jaruzelski, who is now 84 and in poor health, says he had to act to prevent a Soviet invasion of Poland.

If found guilty he faces up to 10 years in prison.

Although there is little public clamour in Poland to send Mr Jaruzelski to prison, a crowd of journalists and members of the public packed the courtroom as the trial began.

Gen Jaruzelski and three of his co-defendants were identified before a panel of judges.

Four of the eight accused men were absent, citing poor health.

'Lesser evil'

Reading the charges, the prosecutor said the men had violated their own communist constitution when they created what he called a "criminal military organisation" to implement martial law in December 1981.

The trial, in Warsaw, marks the first time Poland has held its former communist leaders criminally responsible for imposing martial law.

Immediately after the fall of communism in 1989, the new Solidarity government rejected calls for political retribution.

But in recent years moves to bring the senior communist party leaders to account for martial law have hastened.

Gen Jaruzelski has always maintained he chose the lesser evil when he ordered tanks onto the snowbound city streets on that night in 1981.

If he had not acted against Solidarity, he says, Soviet troops would have.

According to surveys, many Poles believe him.

|

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Oct 10, 2008 11:13:48 GMT 1

The final stage of anti-communist protest lastest the longest - from 1980 to 1989. The political ferment which was started by the creation of Solidarity movement in 1980 was never suppressed by the authorities. It went up or down, but never ceased.

The history of Solidarity (Polish: Solidarnoœæ (help·info) IPA: [sɔlidarnɔɕt͡ɕ]), a Polish non-governmental trade union, began in August 1980 at the Lenin Shipyards (now Gdañsk Shipyards) where it was founded by Lech Wa³êsa and others. In the early 1980s, it became the first independent labor union in a Soviet-bloc country. Solidarity gave rise to a broad anti-communist nonviolent social movement that, at its height, united some 10 million members and vastly contributed to the fall of communism.

Poland's communist government attempted to destroy the union by instituting martial law in 1981, followed by several years of political repression, but in the end was forced to begin negotiating with the union. The Roundtable Talks between the government and the Solidarity-led opposition resulted in semi-free elections in 1989. By the end of August 1989, a Solidarity-led coalition government had been formed, and, in December 1990, Wa³êsa was elected president. This was soon followed by the dismantling of the communist governmental system and by Poland's transformation into a modern democratic state. Solidarity's survival meant a break in the hard-line stance of the communist Polish United Workers' Party (PZPR), and was an unprecedented event not only for the People's Republic of Poland—a satellite of the USSR ruled by a one-party communist regime—but for the whole of the Eastern bloc. Solidarity's example led to the spread of anti-communist ideas and movements throughout the countries of the Eastern Bloc, weakening their communist governments; a process that eventually culminated in the Revolutions of 1989.History of Solidarity en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Solidarity

Early strikes (1980)

Strikes did not occur merely due to problems that had emerged shortly before the labor unrest, but due to governmental and economic difficulties spanning more than a decade. In July 1980, Edward Gierek's government, facing economic crisis, decided to raise prices while slowing the growth of wages. At once there ensued a wave of strikes and factory occupations, [1] with the biggest strikes taking place in the area of Lublin (first strike started on July 8, 1980 in the Communications Equipment Factory in Œwidnik). Although the strike movement had no coordinating center, the workers had developed an information network to spread news of their struggle. A "dissident" group, the Workers' Defence Committee (KOR), which had originally been set up in 1976 to organize aid for victimized workers, attracted small groups of working-class militants in major industrial centers.[1] At the Lenin Shipyard in Gdañsk, the firing of Anna Walentynowicz, a popular crane operator and activist, galvanized the outraged workers into action.[1][7]

On August 14, the shipyard workers began their strike, organized by the Free Trade Unions of the Coast (Wolne Zwi¹zki Zawodowe Wybrze¿a).[8] The workers were led by electrician Lech Wa³êsa, a former shipyard worker who had been dismissed in 1976, and who arrived at the shipyard late in the morning of August 14.[1] The strike committee demanded the rehiring of Walentynowicz and Wa³êsa, as well as the according of respect to workers' rights and other social concerns. In addition, they called for the raising of a monument to the shipyard workers who had been killed in 1970 and for the legalization of independent trade unions.[9]

The Polish government enforced censorship, and official media said little about the "sporadic labor disturbances in Gdañsk"; as a further precaution, all phone connections between the coast and the rest of Poland were soon cut.[1] Nonetheless, the government failed to contain the information: a spreading wave of samizdats (Polish: bibu³a),[10] including Robotnik (The Worker), and grapevine gossip, along with Radio Free Europe broadcasts that penetrated the Iron Curtain,[11] ensured that the ideas of the emerging Solidarity movement quickly spread.

On August 16, delegations from other strike committees arrived at the shipyard.[1] Delegates (Bogdan Lis, Andrzej Gwiazda and others) together with shipyard strikers agreed to create an Inter-Enterprise Strike Committee (Miêdzyzak³adowy Komitet Strajkowy, or MKS).[1] On August 17 a priest, Henryk Jankowski, performed a mass outside the shipyard's gate, at which 21 demands of the MKS were put forward. The list went beyond purely local matters, beginning with a demand for new, independent trade unions and going on to call for a relaxation of the censorship, a right to strike, new rights for the Church, the freeing of political prisoners, and improvements in the national health service.[1]

Next day, a delegation of KOR intelligentsia, including Tadeusz Mazowiecki, arrived to offer their assistance with negotiations. A bibu³a news-sheet, Solidarnoœæ, produced on the shipyard's printing press with KOR assistance, reached a daily print run of 30,000 copies.[1] Meanwhile, Jacek Kaczmarski's protest song, Mury (Walls), gained popularity with the workers.[12]

On August 18, the Szczecin Shipyard joined the strike, under the leadership of Marian Jurczyk. A tidal wave of strikes swept the coast, closing ports and bringing the economy to a halt. With KOR assistance and support from many intellectuals, workers occupying factories, mines and shipyards across Poland joined forces. Within days, over 200 factories and enterprises had joined the strike committee.[1][7] By August 21, most of Poland was affected by the strikes, from coastal shipyards to the mines of the Upper Silesian Industrial Area (in Upper Silesia, the city of Jastrzêbie-Zdrój became center of the strikes, with a separate committee organized there). More and more new unions were formed, and joined the federation.

Thanks to popular support within Poland, as well as to international support and media coverage, the Gdañsk workers held out until the government gave in to their demands. On August 21 a Governmental Commission (Komisja Rz¹dowa) including Mieczys³aw Jagielski arrived in Gdañsk, and another one with Kazimierz Barcikowski was dispatched to Szczecin. On August 30 and 31, and on September 3, representatives of the workers and the government signed an agreement ratifying many of the workers' demands, including the right to strike.[1] This agreement came to be known as the August or Gdañsk agreement (Porozumienia sierpniowe).[7] Another agreement was signed in Jastrzêbie-Zdrój on September 3. It was called the Jastrzêbie agreement (Porozumienia jastrzebskie) and as such is regarded as part of the Gdañsk agreement. Though concerned with labor-union matters, the agreement enabled citizens to introduce democratic changes within the communist political structure and was regarded as a first step toward dismantling the Party's monopoly of power.[13] The workers' main concerns were the establishment of a labor union independent of communist-party control, and recognition of a legal right to strike. Workers’ needs would now receive clear representation.[14] Another consequence of the Gdañsk Agreement was the replacement, in September 1980, of Edward Gierek by Stanis³aw Kania as Party First Secretary.[15]www.solidarnosc.gov.pl/?document=48The anniversary poster  Strike in the shipyard.  Count on me  Walesa speaks to workers  What struck foreign journalists and observers was the religiousness of workers.  21 postulates to the government   The famous room where the talks took place. The Lenin bust on the right.   The members of the Strike Comittee.  Communist government`s delegate  Communist propaganda posters   Workers` families gathered at the fence every day. People feared another massacre similar to one in 1970.    Independent prinitng press   Polish history milestones    Negotiations  Triumph. The government gave in.  ![]() [http://www.solidarnosc.gov.pl/gallery/gazeta/18/015-Stocz.80.JPG/img]  Signing the pact  Walesa is using a famous giant pen.    It displays a photo of the Pope, today it is in the museum.  |

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Oct 10, 2008 11:42:33 GMT 1

|

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Nov 11, 2008 22:17:43 GMT 1

Ryszard Kowalczyk (born 20 February 1937) and his younger brother Jerzy Kowalczyk (born 1942) - Polish brothers who planted a bomb as a protest. The Kowalczyk brothers were scientists at Opole University. They planted a bomb there on 6 October 1971 as a protest against the violence perpetrated by the communist authorities against the workers' protest. A big celebration for the Secret Service and socialist police was to take place at the University assembly hall on the following day. Although no-one was injured, the Kowalczyks were quickly captured. On 8 September 1972 the Opole court sentenced Jerzy to death and Ryszard his helper to 25 years in prison. The sentence was confirmed by the Supreme Court on 18 December 1972. Such severe sentences resulted in protests involving Jan Józef Szczepański, Wisława Szymborska, Jerzy Szacki, Stanisław Lem, Daniel Olbrychski and Catholic authorities. On 19 January 1973 the Council of State reduced Jerzy Kowalczyk's sentence to 25 years in prison. With the rise of Solidarity in the 1980s, pardons were issued and the brothers were freed for good behaviour: Ryszard in 1983 and Jerzy in 1985. In 1991 President Lech Wałęsa decided that their sentences were legally forgotten which also allowed them to work again. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kowalczyk_brothersThe destroyed assembly hall of the University  Ryszard Kowalczyk www.nto.pl/apps/pbcsi.dll/bilde?Site=NO&Date=20081001&Category=POWIAT01&ArtNo=597021664&Ref=AR&MaxW=185&border=0&title=1 |

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Dec 6, 2008 23:01:03 GMT 1

Redemption for the Polish Leader Who Crushed Solidarity?

By Beata Pasek/Warsaw

Time

11/29/08

General Wojciech Jaruzelski (L), Poland's last communist-era leader, and former head of the Polish communist party Stanislaw Kania (R) leave court after General Wojciech Jaruzelski (L), Poland's last communist-era leader, and former head of the Polish communist party Stanislaw Kania (R) leave court after a hearing in the long-running legal case over the former regime's martial law crackdown in 1981, on April 24, 2008 in Warsaw.

Janek Skarzynski / AFP / Getty

In December of 1981, General Wojciech Jaruzelski imposed martial law on Poland, orchestrating a brutal crackdown on the pro-democracy Solidarity trade union movement that eventually saw some 90 people killed, and around 10,000 detained in internment camps. But as Jaruzelski and six other former top officials set out their defense in a criminal trial over their coup and crackdown, many of the former leaders of Solidarity have emerged among the general's staunchest defenders. In a bizarre twist of history, the leaders of the very movement Jaruzelski sought to crush 27 years ago now say he was right, at the time, to curb Solidarity's growing appetite for power.

In his lengthy defense statement at the Warsaw regional court, Jaruzelski, who was prime minister at the time as well as the head of the Communist Party, explained his motivation for declaring martial law this way: In 1981, he argued, the Solidarity movement was in the throes of an internal power struggle between radicals and moderates, with Moscow watching closely, having reinforced the Soviet troop contingent stationed in Poland. The Soviets had previously sent troops to crush a popular rebellion in Hungary in 1956, and to brutally destroy a reformist Czech communist regime in 1968, and Jaruzelski was acutely aware of the danger that Poland could suffer a similar fate. Martial law was "a dramatically difficult decision," but it "saved Poland from a looming catastrophe, " according to Jaruzelski.

"Solidarity did not want to rein in its political aspirations, " the general argued. "Because of the geopolitics, the authorities could not step back. There was a knot which we decided to cut ourselves." The crackdown, however brutal, was a "lesser evil" that spared Poland the a direct Soviet military intervention, he argued. He acknowledged that martial law brought human suffering, for which the general said he "is sorry and takes the responsibility. "

While the question of whether the Soviets were ready to start an invasion is still debated by historians, Jaruzelski's background may have made him more prone to fear that Moscow would intervene. As a 17-year-old during World War II, he had been deported with his parents to Siberia after Soviet forces entered Poland. His father was imprisoned, and young Jaruzelski logged trees. "He had no illusions about Russia," says Stefan Chwin, a Polish writer. Even Lech Walesa, the legendary Solidarity leader interned for almost a year during the clampdown, feels empathy for Jaruzelski. "He belongs to an unfortunate generation broken by (historic) circumstances, " Walesa said in a radio interview. "Had he lived in other times, he would have been a great patriot." Walesa believes the trial is "a mistake", and emphasizes that Jaruzelski eventually prepared the way for democracy in Poland by starting the Round Table talks with Solidarity that brought about the peaceful end of the the communist regime in 1989.