|

|

Post by Bonobo on Dec 8, 2008 13:04:11 GMT 1

After signing Gdañsk Agreement in August 1980, the government had to make further concessions. Solidarity was registered in September, soon encompassing large part of the population, nearly 10 million people. Even socialist militiamen and other regime services tried to set up the Solidarity cells in their work places but to no avail as they were immediately fired. Party members gave up their membership en masse. Socialism was crumbling on people`s eyes. The lines to shops became longer, buying meat or sausage was a matter of incredible luck, that is why the regime introduced rationing. But it didn`t cover the needs, either. E.g., in winter 1981/82 the regime realised they didn`t produce 600.000 pairs of shoes and boots. Simply speaking, some official didn`t include them in the plan of production. In a socialist economy everything had to be comprised in a plan, so if it wasn`t, it didn`t exist. The foreign debt amounted to incredible 26 billion $, and interest rates had to be paid. The export of goods to earn hard currency deprived Polish internal market of many nessecities. I remember how happy my mother was when she managed to buy a giant sack of potatoes straight from the farmer. We put it in the basement and were secure about our winter supplies. The blackouts/power cuts became a frequent thing because coal was exported to earn Poland hard currency and the needs of energy consuming industry had to be covered first. In result, individual energy recipients had to live without power for one or two hours every day. The regime had a hard time because the former one left the debt totalling 26 billion $. With a Polish export worth 10 billion$ a year it was impossible to pay the loans, which burdened the economy with new interest rates every year. People got tired by shortages and hard conditions. Also they got tired by communists` resistance to give more freedom to people. Concessions that communists had already made (e.g., less strict censorship in the press, journalists could write about many things which had been banned before) were not enough, e.g, T.V. belonged to the regime, propagated lies and misinformation, making people really angry. Strikes broke out not only in major companies (which were all state) but in small ones too. At universities and schools, hospitals, public transport stations, offices, mines, plants, shipyards etc etc. Strike at city transport station in Wrocław  Bus drivers  Students fought for the political independence of universities     www.strajki.pl/index.php?url=5&val=26&gal=108&what=styczen www.strajki.pl/index.php?url=5&val=26&gal=108&what=styczenPeople organized hunger strikes amd hunger marches. But food had to be exported to earn dollars to repay the national debt. The starving of all countries - unite!  Communist rulers deprived us of our candies/sweets! (that was true - I had to eat rationed sugar instead of chocolate or candies).  The effect of the Party Summit - cutting rations!  There were road strikes too.  And mass demonstrations - Free political prisoners!    The authorities introduced rationing: meat, sweets, flour, fats, pasta (sugar was already rationed in 1976). Meat rationing card  10 million Poles joined Solidarity. They demanded more political freedom but also expected that the government would introduce some sane healthy measures to improve the tragic economic situation. They didn`t realise that the condition of inefficient economy was hopeless. |

|

|

|

Post by tufta on Dec 8, 2008 14:22:38 GMT 1

bonobo, tufta, how do you guys feel about jaruzelski? I don't feel anything very much  The closest something I feel is pity for him. He beacame a traitor of Poland, caused deaths of innocent people, imprisoments, he took off some 10 precious years from Polands history, he broke lives of many Poles. Yet he is unable to admit his guilt, and to ask for forgiveness. He is closing himself in thick, solid shell of evil. Poor guy. I wish he would be able to come out of it. |

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Dec 9, 2008 19:52:34 GMT 1

I don't feel anything very much  The closest something I feel is pity for him. He beacame a traitor of Poland, caused deaths of innocent people, imprisoments, he took off some 10 precious years from Polands history, he broke lives of many Poles. Yet he is unable to admit his guilt, and to ask for forgiveness. He is closing himself in thick, solid shell of evil. Poor guy. I wish he would be able to come out of it. Show more compassion for the old guy. ;D ;D ;D Yes, he made his dirty job. But if it hadn`t been him, somebody else would have probably taken over, tried to introduce martial law anyway and fluffed it, thus provoking Soviet invasion. There wasn`t a real chance for Poland to leave the socialist camp. Don`t forget the Cold War was alive and kicking at the time. Soviets wouldn`t care much about world`s public opinion,just like they hadn`t in 1968. They made an invasion on Czechoslovakia and what? Was a single shot fired from the West in defence of Czechs and Slovaks? For me Jaruzelski is a tragic figure, just like Judas who got a nasty role to play and had to act it out so that the biblical story could be fullfilled. |

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Dec 12, 2008 11:53:19 GMT 1

Some of you probably remember posts in other forums about martial law. Here are they again. Tomorrow there is an anniversary. "" They came at about 1 am. Three of them. With a crowbar, truncheon and handcuffs. They said they were taking my husband to Bia³o³êka, claiming there was a decree proclaimed. They were noisy, rude, and in a great hurry. The older daughters were standing silent and terrified. The younger ones were crying loudly . "25 years ago General Jaruzelski, backed by the police, secret police and the Polish army as well as party leaders and members, introduced the martial law in order to suppress Solidarity and crush the nation`s aspirations for more soveignty and independence in the communist block. The martial law had been prepared for months. The date of 13 December wasn`t chosen by pure accident. Firstly, the regime was ready to strike. Secondly, on 15 December, a lot of drafted soldiers were to go home after a 2 year service in the army. The leave of experienced soldiers would substantially diminish the army`s capacity to introduce the martial law. Thirdly, desperate Solidarity planned mass demonstrations and strikes on 17 December. Solidarity leaders had been getting impatient with the regime`s reluctance to reach a serious compromise, that`s why some of them became radical hawks and openly called for showdown with the regime. The regime seemed weak in comparison with powerful Solidarity which boasted of having 10 million members, while the party had 2 million, continually abandoning the ship. Solidarity leaders and common people thought it was enough to press harder and the regime would collapse. Events soon proved how wrong they were. The regime managed to keep their plans secret. There were a few leaks from befriended policemen but nobody knew anything for sure at lower levels of the forces, that is why their vague warnings were ignored. Some people reported the discreet movement of troops in the country, but that was ignored too. The regime attacked on many fronts on the night of 13 December. The most important actions and regulations: 1. They cut off phone lines in the whole country to reduce the possibility of Solidarity members warning each other. Phones didn`t wirk for about two months (?). Nobody estimated how many seriously ill people died because the ambulance service didn`t get to them on time. 2. All radio and TV programmmes stopped. At 6 am there was a speech by General Jaruzelski, repeated for many hours, intertwined with classical music and war marches. Of course, there was the news in the evening, the speakers were wearing military uniforms without ranks. 3. About 3 thousand people were arrested and sent to detention centers. It was called the internment. They were dragged out of their beds by police teams, often after breaking the door. Altogether about 10 thousand people were interned during the martial law. Not only Solidarity leaders, also celebrity people who where suspected of being in opposition to the regime, e.g., artists and writers. Most of the latter ones were soon released but interning them was a very bad publicity for the regime anyway. 4. Heavy armoured vehicles appeared on the streets of major cities. Tanks, personnel carriers and trucks, next to them armed soldiers and militiamen. They blocked the roads, checked people`s papers, ransacked cars. 5. Military commissars i.e. army officers, were appointed as directors or managers to factories, ministries, offices, organizations etc. 6. All independent trade unions, both worker and peasant, were made illegal. Some organizations, e.g. The Union of Polish Journalists (it had gotten too independent before) and PenClub were dissolved. Only two government papers were allowed for publication. 7. Factories had to adopt the military style of work - heavy punishments awaited those who committed the slightest offence. Going on strike and showing disobedience to martial law regulations was a major offence. 8. Travels to other cities or countries were halted, all those waiting at Okêcie Airport were turned back. To travel to another city you had to have a pass. 9. Schools broke up for two months. 10. The censorship was imposed on mail. Envelopes were opened and letters were looked through. The declaration of martial law: Two films with photos of the period Another film PS. Streets in many pictures look quite foggy. It`s not fog, though, it`s tear gas. PS2. I remember there was no "Teleranek" on TV, my favourite programme for children which I used to always watch on Sunday mornings. From that day on I started disliking General Jaruzelski and his regime and I put all my juvenile emotions into it. I also remember the speech which we were listening to on the radio in the kitchen at breakfast time. My parents cried and that was absolutely shocking to me. But later there was no school for several weeks and I was so happy. And I liked Polish war films they showed on TV. They came at night, as clandestinely as criminals. They were ones. homepage.mac.com/zbigniew/wstanie/pages/strona_004.html |

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Dec 12, 2008 11:59:22 GMT 1

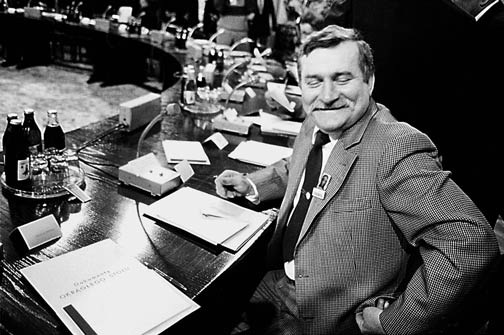

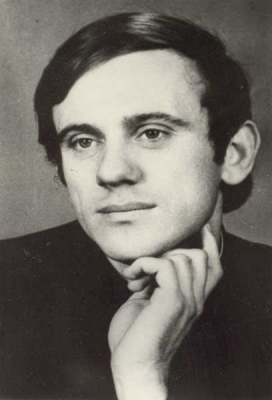

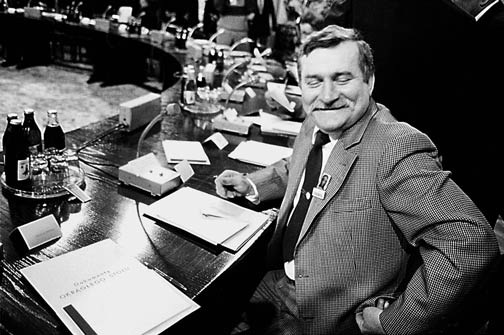

Photos of the time: Broadcast of Wojciech Jaruzelski declaring martial law (December 13, 1981)  Probably the most famous photo of the martial law, full of symbolic messages. The armoured vehicle is standing in front of the "Moscow" cinema. The film on is " Apocalypse Now" by Francis Coppola. The photo was taken by a foreign reporter.  Those men introduced the martial law. WRON - The Military Council of National Rescue.  Zołnierz Wolności (Soldier of Freedom was one of two papers which were allowed for publication.  The TV news presenters wore military uniforms.   General Jaruzelski pays a visit to soldiers on a patrol.     General Wojciech Jaruzelski`s speech to the communist party members at a secret meeting:

The crisis has moved into its culminating phase. The counterrevolutionary forces overtly disclosed their intentions. […] In the nearest future, we should try to approach the state of confrontation imposed by the opponent from the best positions. Not one step back. […]

We will have to make decisions of utmost responsibility. We have enough experience to fight desperately for that which can be saved. I counted on workers’ class instinct. Unfortunately, we proved to be too week, inept; we failed to go full steam ahead. We made wrong decisions and assessments. But we meant well and still do.

It is a terrible, macabre shame that, after 36 years in power, the party must be defended by police force. But there is nothing else for us to do. One should be prepared to make decisions that will permit to save the basics.Police against nation. Many thousand „Solidarity” activists and well-wishers were detained unlawfully      Warsaw  Gdańsk, in front of the shipyard  General Florian Siwicki (chief of the General Staff of the Polish Army) at a meeting of the party’s Political Bureau:

For now, we have reached our goal. […] The army’s cooperation with the police and the security service is very good. We broke through the first position - the enemy is paralysed but not defeated. Conclusions:

1. Maintain martial law, armed forced in starting positions, grip on the enemy still unrelaxed.

2. Authorities at all levels must strictly enforce martial law discipline and rigours.

3. In justified cases, strength should be demonstrated and rigours should not be relaxed during the Christmas period. But, simultaneously, the discomforts of martial law should be eased wherever possible.

4. Once a strike is broken or an enemy isolated, there should be no political void. We must fight for minds, we need massive commitment of party forces.

In December 1981 I was young and rather unaware of the situation because politics was boring to me. I prefered my books, for school and not only, I also started to be interested in girls. In 1982 I left primary school and went to a high school and that was connected with passing entrance exams. I studied hard. But my political education was growing rapidly after December 1981. When in the high school in September 1982, I was fully aware of my strong reluctance to communism and those who implemented it in Poland. I wasn`t alone - during school years most of us were against. We were children of the martial law. Tough, confirmed anticommunists. No wonder communism was doomed to fall. ;D ;D ;D    Desecrated monument of Lenin www.pbase.com/zyziza/image/71723249Strike in steel plant December www.pbase.com/zyziza/image/71723248Detention www.pbase.com/zyziza/image/71619377 These and more pictures here www.pbase.com/zyziza/martial_law_in_polandAnother film with photos The martial law was implemented by Poles against other Poles. Soviet troops didn`t participate in it. General Jaruzelski had consulted his Soviet military superiors, that`s natural, apart from being the Prime Minister, he was also the head of Polish Armed Forces and as such he stood to attention before Marshall Kulikow, the commander of the Warsaw Pact. General Jaruzelski and others have always claimed that they had to introduce the martial law because there was an imminent threat of Soviet intervention in Poland. They simply chose the lesser evil - home crackdown instead of foreign invasions and probably war. However, documents available today prove that Soviets didn` t have any intention to invade Poland in Czechoslovakia-1968-style. One Afghanistan was enough for Soviet leaders at the time, they didn`t want to get into another quagmire in Poland. But they took every chance possible to exert pressure on Polish leaders to crack on Solidarity at last. The independent workers` movement and union meant a deadly danger to the communist system whose very nature is to keep everything under the state control. Solidarity couldn`t be controlled, so it had to be destroyed to avoid giving a bad example to other socialist countries. Soviet and socialist countries` governments welcomed the martial law with enthusiasm and full support. The governments of Western European countries sighed with relief that at last "the crisis" in Poland was settled. Common Westerners showed great sympathy to Poles - Germans, the French, Scandinavians and others sent millions of parcels with food and clothing to Poland during the hardest time. The US government answered with embargo on trade and loans. Queues in front of shops and empty shelves were a day-to-day nightmare of those times. The butcher`s in socialist economy  |

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Dec 12, 2008 12:16:04 GMT 1

|

|

|

|

Post by tufta on Dec 12, 2008 13:07:55 GMT 1

Bus drivers  are you quite sure? ;D |

|

|

|

Post by tufta on Dec 12, 2008 13:15:56 GMT 1

like Judas who got a nasty role to play and had to act it out so that the biblical story could be fullfilled. Well, let's not exaggerate. As far as I remember Judas was very much admitting he served evil. So admitting that he couldn't bear it and committed suicide. Which is again not too wise as it is kind of 'shutting God' mouth, or is it not? The 'nasty role' to be played by Judas as a part of Goddly plan is very, I mean, VERY heretic asumption, although quite popular lately in some circles ;D I am saying heretic, not 'surely untrue', mind the difference. |

|

|

|

Post by valpomike on Dec 12, 2008 13:25:58 GMT 1

We here, in the U.S.A., and thank God for it, have never been in that spot, and I hope we never will be.

This could happen with this new leader, we get next month.

Mike

|

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Dec 12, 2008 22:48:53 GMT 1

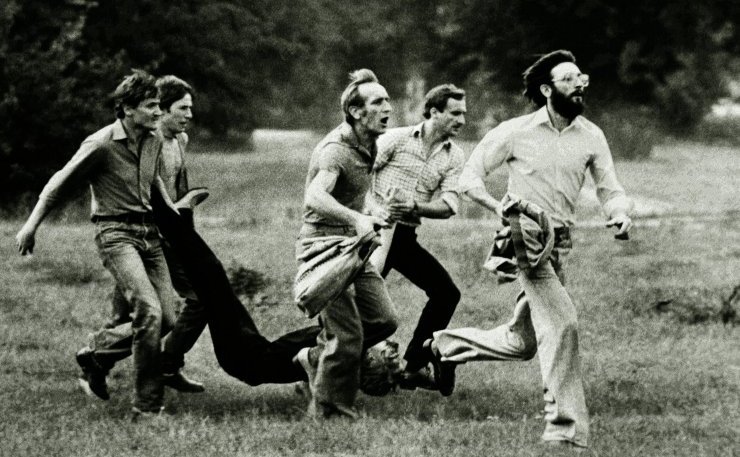

Well, let's not exaggerate. As far as I remember Judas was very much admitting he served evil. So admitting that he couldn't bear it and committed suicide. Which is again not too wise as it is kind of 'shutting God' mouth, or is it not? The 'nasty role' to be played by Judas as a part of Goddly plan is very, I mean, VERY heretic asumption, although quite popular lately in some circles ;D I am saying heretic, not 'surely untrue', mind the difference. They have also called me heretic in other Polish forums. I wonder why it is so. ;D ;D ;D ;D ;D ;D If sb calls me that for the third time, I will go to a theologian for advice. More on martial law. Many people were paralysed by the declaration of martial law. Many were glad that at last there would be peace and quiet in the country. However, many others decided to resist. Workers, organised in big groups in major plants, shipyards and mines decided to lock themselves up in their workplaces and defend them against the police and the army. However, the regime expected and was prepared for workers` resistance. The typical scenario was that the armed forces arrived at a plant and workers were addressed through loudspeakers to leave. After they didn`t obey, the gates of the plant were crushed by tanks, and the riot police stormed through the hole. Then there was beating and arresting. Such events took place in all major factories in Poland. The greatest tragedy happened in Wujek coal mine in the industrial region od Silesia. Workers got very determined, they decided to defend at all cost. They armed themselves with metal bars, clubs, stones and bricks, slings and metal bolts. After the tanks crushed the gate, a regular battle started. It was a hand-to-hand fight lasting for a few hours, during which miners overpowered a tank and defended themselves very gallantly. Eventually, the special police unit started shooting, 7 defenders were killed on the spot, two died in hospital, about 20 were injured. The defence was stopped. The policemen and soldiers were so brutal they initially didn`t allow ambulances to take the wounded to hospitals. The massacre at Wujek mine has always been seen as the symbol of workers` sacrifice for freedom and the shocking brutality of the communist regime who fought against its own peoples and was ready to kill in order to defend socialism. Defend socialism against workers. A site with pics, click on the photo to enlarge it www.solidarnosc25foto.info/wujek.htm ![]() [/img] ![]() [/img] ![]() [/img]    Coal wagon as a barricade.  The beginning of the pacification. Picking up a brick.  Throwing a brick at a tank.  First wounded.   The police chase miners and residents of nearby houses.   Detention  Tear gas attack. Miners are trying to barricade the hole in the fence after it has been crushed by a tank.    A miner is drinking to an overpowered tank.  Bullet holes in the wall.  Ammo.  The tragedy.     Funeral  The fence of the mine in 1983  The monuments to the fallen miners.     Memory   Some photos. wyborcza.pl/5,77023,598880.html?i=5 miasta.gazeta.pl/katowice/5,35061,763878.html ligarepublikanska.tripod.com/idz-i-zabij/zdjecia.htmThe comic book about the massacre  A stamp  |

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Dec 21, 2008 15:45:22 GMT 1

Reagan preferred martial law to USSR intervention?

thenews.pl

17.12.2008

According to an insider in the Ronald Reagan's administration, the US may have preferred the introduction of martial law in Poland to

military intervention by Warsaw Pact forces.

In February 1981 Richard Pipes became the Director of East European and Soviet Affairs bureau of the National Security Council under Ronald Reagan.

In an interview with Marcin Bosacki of Gazeta Wyborcza Pipes says

that Reagan's administration possessed very detailed information

about preparations of the communist regime to introduce martial law.

"It remains a secret to me why this information was not used. Did the people who received it fail to believe it was real? Or did they

prefer Jaruzelski to impose martial law because they thought the only alternative would be Soviet intervention? I don't know. I only know that the information was not operated on. And so, when on December 13 Jaruzelski declared martial law, even the White House seemed surprised," reveals Pipes.

Pipes explained that the data came from Ryszard Kuklinski, a Cold War spy who between 1971 and 1981 passed on thousands of top secret Warsaw Pact documents to the CIA.

Martial law was imposed on December 13, 1981 to crush the pro-

democratic Solidarity Trade Union. Under martial law over ten

thousand people were arrested without charge, with over three

thousand interned and over 100 killed.

General Jaruzelski – currently on trial with other generals of the

period for their role in the crackdown – has since defended his

decision as the "lesser evil" and the only way to prevent Soviets

from invading Poland.

Tribute to 1970 victims of communist rule

Poland.pl

2008-12-17

Ceremonies honoring the victims of the tragic December protests on

the Baltic coast in 1970 have been held in Gdynia.

Speaking at the gathering president Lech Kaczynski said that the

consequence of this strong worker rebellion had been the creation of

pro-democratic movements leading ultimately to a Poland rid of

communist rule. Unveiling a commemorative plaque during a wreath

laying ceremony in front of the monument to the fallen protesters

near the Gdynia shipyard, the president recalled:

`It's been a tradition here since 1970. It seemed the impetus

subsided in the first years of the decade, but it regained strength

from 1975 leading to the creation of the first widely known, though

still illegal then, free trade unions and ultimately to the historic

victory of Solidarity in August 1980.'

According to official records, the December protests of 1970 claimed

the lives of 44 persons. Over 1100 were wounded in clashes with

police and army units which fired at the demonstrators. polandsite.proboards104.com/index.cgi?board=polishhistory&action=display&thread=70&page=2#2112

Memory to Wujek coal mine massacre

thenews.pl

15.12.2008

A 'House of memory' has opened at the Wujek coal mine, southern Poland, to commemorate those who died while protesting against the imposition of martial law, 27 years ago.

A model depicting the brutal break up of the demonstration, built by a team of Warsaw modellers led by Jan Nalecz is also on display.

December 16 is the anniversary of one of the most dramatic events in the history of Katowice, where nine miners were shot dead and many more were wounded in the Wujek Coal Massacre, possibly the greatest crime of the martial law period in Poland, 1981.

A protest in the Wujek coal mine was launched after the introduction of martial law, when the head of the mine's 'Solidarity' chapter, Jan Ludwiczak was detained by the authorities. On December 14, rhw daye after martial law was declared saw the first group of people pressing for the release of Ludwiczak and other "S" activists.

The action was joined by other miners calling for the lifting the martial law and reinstating 'Solidarity' as a legal trade union.

The "S" audit committee secretary Stanislaw Platek was chosen as the leader of the strike.

When negotiations with the authorities failed, a strike committee was launched, with about 50 workplaces striking during the first days of martial law.

Having learnt that the police had pacified some of them, on 15 December, miners started preparations for defending their mine with the help of spades, picks and bricks.

On December 16, the Wujek coal mine was surrounded by police, tanks and military vehicles. Protesters were attacked with tear gas and water cannons, regardless of 16 degrees below zero temperature.

Tanks forced down the walls and the feared ZOMO militia entered the area of the mine, and six miners were shot dead on the spot, and three of them consequently died in consequence of the injuries.

Following these events, there talks were held by the representatives of both sides, bringing the strike to an end. Eight miners were detained on a charge of leading the strike, with four of them acquitted and another four imprisoned for 3 and 4 years.

The inquiry into the deaths was remitted in 1982 and re-launched in 1993.

A court in Katowice sentenced 14 former ZOMO policemen to several years in prison. The former leader of the ZOMO platoon Romuald Cieslak was given a sentence of 6 years imprisonment, with two of his subordinates facing 4 years and another 11 to three and a half years. These sentences were increased in another trial in June this year.

The question of compensation for the shot miners' families remains unsolved, with families' legal representatives saying that they may file another law suit.

Giving vent to their dissatisfaction with the lack of any resolution in the case, the members of the Social Committee of Remembrance of the Wujek coal miners, who for years have prepared celebrations under the memorial cross, a monument dedicated to the Wujek miners, have decided not to invite state officials.

Protesters, supporters outside Jaruzelski's house

thenews.pl

13.12.2008

Proponents and opponents of General Wojciech Jaruzelski's rule have gathered in front of his house to commemorate the 27th anniversary of the introduction of martial law in Poland.

For some Wojciech Jaruzelski is a hero, but for others he is a

military dictator guilty of numerous crimes against the nation.

Members of Polish Left Rightness (Racja Polskiej Lewicy)

organization, for whom Wojciech Jaruzelski remains a hero, were

shouting, "May the general live to be a hundred, banners

saying "Leave the general to history" and "Leave the general in

peace."

His opponents, in the shape of the far-right All- Polish Youth

(Mlodziez Wszechpolska) plus anarchist organizations, who think that Jaruzelski is guilty of the deaths and imprisonment during martial law, were standing separated by the police.

"I came here to demonstrate my solidarity with the general, a man who made a decision that was extremely difficult both for him and for the country. It was a choice that saved Poland from the tragedy of Warsaw Pact troops entering Poland," said Maciej Jonas of the Young Social Democrat Federation.

A representative of a leftist party assessed the general in a

different way: "General Jaruzelski was a military dictator who tried

to ruin the greatest workers' movement in Polish history."

The Free Speech Organization will organize an event to recall the

fight against communist rule and preserve the memory about it among the younger generation. Participants will take a special tram from the general's house to the headquarters of the organization, where a concert will be held.

|

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Jan 7, 2009 21:43:06 GMT 1

Here is the news so that you won`t think ALL Poles hated communism. There were exceptions....

But the poll results remind me of a joke about an old French aristocratic woman who, when asked about the best time of her life, answered: The French Revolution. What, are ytou nuts, the Revolution, with this terror against aristocrats, wars, etc etc???

Yes, she said, but I was 18 then.

As Poland prospers, less nostalgia for communism

DPA

1/5/09

Warsaw - With a rise in the standard of living and European Union

membership, fewer Poles now feel nostalgia for the days of

communism, the daily Rzeczpospolita reported on Monday. Twenty-seven per cent say communism was the best period for Poland, according to a survey in the daily of 1,004 people. The number is down from seven years ago, when 42 per cent reported they remembered that period fondly.

Older Poles aged 50 and above have the highest sentiment for

communism - the 1945 to 1989 period - the daily said, while younger people feel more nostalgia for the 1990s.

The change comes from a rise in the standard of living, sociologist

Andrzej Rychard told the daily, and Poland's entry into the European

Union in 2004.

Younger people, who hardly remember communism, are also now playing a bigger role in society, Rychard said.

|

|

|

|

Post by valpomike on Jan 8, 2009 0:05:07 GMT 1

My Uncle who lives in Warsaw, Poland, and is ninety one years young, hated the communism, and is still scared that they will come back.

Mike

|

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Jan 8, 2009 0:50:01 GMT 1

My Uncle who lives in Warsaw, Poland, and is ninety one years young, hated the communism, and is still scared that they will come back. Mike The one who composed the anthem??? |

|

|

|

Post by valpomike on Jan 8, 2009 5:41:52 GMT 1

No the one who is a retired doctor, Sstanislaw Roszkowski, a doctor, and medical teacher, and a great man.

Mike

|

|

|

|

Post by valpomike on Jan 8, 2009 5:43:09 GMT 1

Dabrowski did not compose it, just named in it.

Mike

|

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Feb 21, 2009 14:57:09 GMT 1

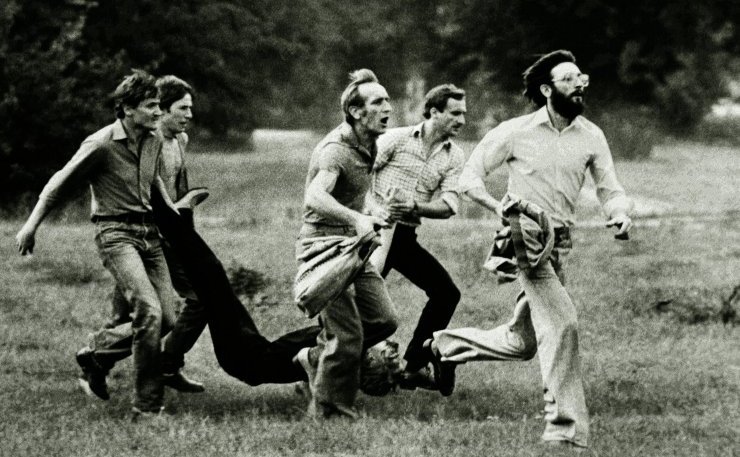

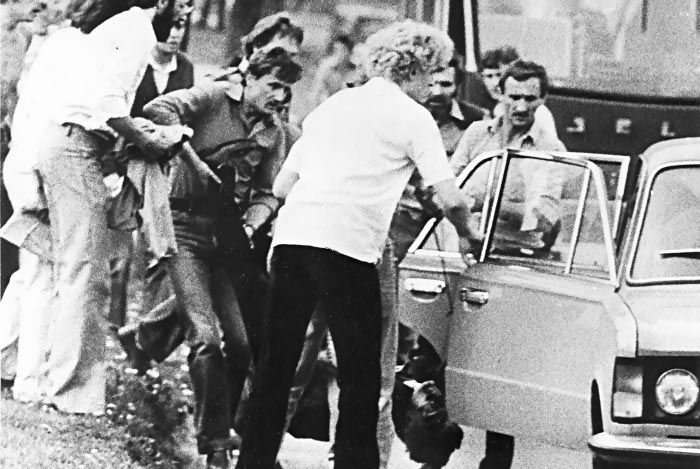

The martial law lasted till 1983. Some people resisted actively by organizing demonstrations to celebrate various anniversaries. Communists put them down, beating people without mercy, sometimes shooting at them. It is estimated that about 100 people died at comunist police`s hands during the martial law. See the site with many pics from demonstrations homepage.mac.com/zbigniew/wstanie/pages/strona_006.htmlhomepage.mac.com/zbigniew/wstanie/pages/strona_007.htmlhomepage.mac.com/zbigniew/wstanie/pages/strona_009.htmlhomepage.mac.com/zbigniew/wstanie/pages/strona_010.htmlhomepage.mac.com/zbigniew/wstanie/pages/strona_011.htmlSite with photos showing the rememberance of of martial law victims homepage.mac.com/zbigniew/wstanie/pages/strona_002.htmland various forms of civil resistance homepage.mac.com/zbigniew/wstanie/pages/strona_012.htmlOne of them was the boycott of state TV. TV NEWS OBJECTORS It happened in 1982 in Świdnik, an industrial town in southern Poland. The time was not too merry, martial law imposed by General Jaruzelski limited people`s freedom to minimum. But they found many ways in which they expressed their disagreement with the regime`s policy. The disagreement which in fact, in conditions of totalitarian system, meant protest. Such nonviolent protest was something that communists couldn`t cope with.

""One evening, just as the nightly television news came on, a Pole fed up with the daily dose of government propaganda got out of his chair, turned his TV set toward the window and went out for a stroll. No one in Swidnik, a factory town 100 miles southeast of Warsaw, claims to know just who made that first "news-walk," but within days almost the entire population of 30,000 began to crowd the tree-lined main street for an evening promenade during the 7:30 newscast. When local authorities clamped on a 7 o'clock curfew to counter the protest, the resourceful residents of Swidnik took a walk during the 5 o'clock news broadcast. Frustrated officials finally lifted the curfew, and after a month of newswalks, Swidnik's citizens decided they had made their point and stayed home—but not before their unique piece of resistance had spread to Olsztyn, Lublin, Bialystok, even Warsaw. Explained a Swidnik news-walker: "Every contact between the people and the authorities can be used to show dissatisfaction with martial law and everyone can do it in his own way."www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,951780,00.html Sites showing detention camps homepage.mac.com/zbigniew/wstanie/pages/strona_008.htmland prisons homepage.mac.com/zbigniew/wstanie/pages/wiezienie.htmlSite with demonstrations www.fotoinfo.pl/filstr22.htm   Constitution Day, 3 May, 1982  www.fotoinfo.pl/filstr26.htm www.fotoinfo.pl/filstr26.htm    The most massive and biggest demonstrations took place on 31 August, 1982, to celebrate the 2nd anniversary of Solidarity. Hundreds of thousands people went out to streets, clashes lasted for many hours till night, several thousand were arrested, cities were totally tear gassed. In Lubin the riot police shot at people killing 3 (it`s described in the next post in this thread). The riot police didn` t pity anyone. They were often drunk or sometimes even drugged.   A sudden attack on unexpecting women  This man was deliberately run over by a riot police truck but he survived, spent two weeks in hospital. The photo is from a famous film shown all over the world at the time.    www.sw.org.pl/hyk-portret.html www.sw.org.pl/hyk-portret.htmlDetained  homepage.mac.com/zbigniew/stan_wojenny_011.htmlhomepage.mac.com/zbigniew/stan_wojenny_010.html homepage.mac.com/zbigniew/stan_wojenny_011.htmlhomepage.mac.com/zbigniew/stan_wojenny_010.htmlLenin desecrated i.pbase.com/g6/82/79282/2/71723249.ODL9CDTP.jpgThe police protect Lenin monument 1982, Gdańsk       Underground printer   wyborcza.pl/5 wyborcza.pl/5,75478,3784566.html?i=12 |

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Feb 21, 2009 15:01:00 GMT 1

|

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Feb 21, 2009 15:37:22 GMT 1

|

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Feb 21, 2009 15:55:46 GMT 1

Pawian, Thank you for sharing these photos. They are indeed "eye-openers." Here in the US, the press made much of the "peaceful" revolution in Poland (I've heard it referred to as the "Velvet Revolution") that brought about the downfall of communism in eastern Europe. It doesn't look all that peaceful to me. In fact I don't remember seeing any images like these during that time. Of course, I was preoccupied with small children at the time which may account for my lack of memory, but I am glad to be informed now. Jeanne I like it that you liked it. Well, the revolution was peaceful on the side of the peoples in the sense they didn`t use arms, however the regime wasn`t so noble. Their brutality sometimes involved cold-blooded murder. In the previous post you can learn about the militia who shot at the crowd and killed 3 demonstrators in Lubin in 1982.  There are about 100 documented victims of the martial law, mostly beaten to death by the police or assassiniated by secret agents. Their burials gave occasions to further manifestation of resentment to the regime and thus fueled the national resistance. Grzegorz Przemyk Birth: 1964 Death: May 14, 1983 Son of a poet Barbara Sadowska. They both were opposition activists. He was arrested on Swietojanska street in Warsaw while celebrating with three friends his high school final exams . Beaten with cruelty by two police officers he died in hospital on 14th May 1983. This murder shocked all Poland. His funeral became a big demonstration against communist government. An old article More opposition to Jaruzelski"Every death is painful, but this one is especially brutal. It will not be forgotten." As the telegram from Lech Walesa, founder of the outlawed independent trade union Solidarity, was read, a hush fell over the mourners who had gathered in Warsaw's St. Stanislaw Kostka Roman Catholic Church last week. Then they burst into applause. The funeral was for Grzegorz Przemyk, 19, a high school senior who died of injuries received from a severe beating by Polish militiamen. His death quickly became a rallying cause for Poles who hate the regime of General Wojciech Jaruzelski.

In one of the largest public gatherings since martial law was imposed 17 months ago, nearly 60,000 people thronged the church for the funeral services and joined in the hour-long procession to the cemetery. Fastened to the front of the casket was a red-and-white Solidarity banner. At the graveside, mourners tossed flowers on the casket and then raised their fingers in the V sign that has become the symbol of Polish resistance to authorities. Many wiped away tears as Przemyk's teacher declared: "Greg, I regret that I didn't have time to prepare you for the brutality of life before it struck you in such a cruel way."www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,925996-1,00.html Obituaries   Funeral     Bogdan Włosik, shot during a demonstration in 1983.  Monument  One more death which shocked Poles. Solidarity priest Jerzy Popiełuszko was assassinated by the communist secret police. The murder was so blatant that the regime was forced to react. The murderers were arrested and received due punishment. On October 19, 1984, a frail, young priest was savagely beaten and drowned by government security agents in the woods of rural Poland. The brutal death of this holy priest, carried out in the dark of night, captured the attention of the world, and his martyrdom is increasingly seen as a sacrifice leading not only to the resurrection of his own country as a free and independent nation of Christian people, but a bloody sacrifice redeeming all enslaved European peoples from the Baltic to the Urals.sunlituplands.blogspot.com/2007/10/remembering-father-jerzy-popieluszko-on_18.html The maltreated body   Funeral   Clandestine Christmas szopka display in a car.  See this site about the funeral stanwojenny.republika.pl/pogrzeb.htmBut they can`t kill the soul!  mib.przasnysz.com/org/pogrzebpopieluszki.jpghomepage.mac.com/zbigniew/wstanie/pages/strona_002.html mib.przasnysz.com/org/pogrzebpopieluszki.jpghomepage.mac.com/zbigniew/wstanie/pages/strona_002.htmlPicture film about the priest with wonderful music by Joan Baez. A programme in English This man was lucky. Though he was deliberately run over by the police truck during a protest demonstration, he survived.    Today he is a middle aged man  This man was beaten by the police in 1982.  |

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Mar 29, 2009 21:37:05 GMT 1

Polish battle against Communism was fought on many levels

DPA

3/24/09

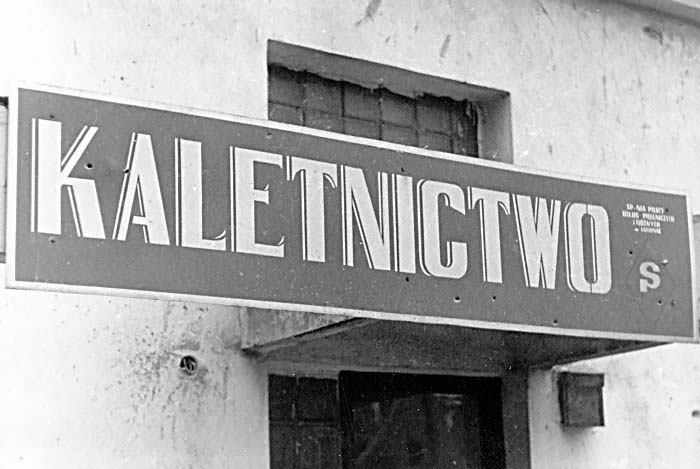

Szydlowiec, Poland - Aniela Wojtowicz is 92 years old, but she still remembers how fear made her knees weak when a government official entered her clothing shop in 1981. It was months before Poland's communist regime would declare martial law in response to the growing Solidarity labour movement. Wojtowicz managed a shop near the market square in Szydlowiec, a small town of 12,000 people two hours south of Warsaw.

That day, she had a stack of Solidarity trade union newsletters behind the counter.

"A man had brought the newsletters - I didn't know his name because I didn't have to - and later another would come and pick them up for distribution, " Wojtowicz said. "But that day I hadn't had time to hide them. The official came in and I got weak. It turned out he only came to look at dresses."

Solidarity had been founded a year earlier, miles away at the Lenin Shipyard in the northern city of Gdansk. It emerged when communist authorities yielded to protestors by allowing the first independent trade union inside the communist bloc. The moustached Lech Walesa, who worked in Gdansk as an electrician, was elected union president in 1981.

At first the union was mostly shipyard workers who demanded better working conditions. But soon Solidarity became a broad resistance movement that included students, miners and factory workers who were members at regional levels.

Thousands of others supported it nationwide by protesting, passing out leaflets or broadcasting illegal radio stations. The risks were jail time, job loss or even death.

Poland's economy was in tatters, with long lines for food and nearly empty shelves. Then a wave of arrests attempted to stifle the growing union before martial law was declared in December 1981.

"When the arrests began, in the evening I heard knocking and two policemen came and asked about my son," Wojtowicz said. "I told them he wasn't there. I'll never forget that fear."

Wojtowicz's son had escaped out the back door the night before when police searched his residence. He'd hid nearby at the home of the town's priest.

The priest in Szydlowiec was Solidarity-friendly and the town's red bricked church was often filled as faith gave comfort in difficult times. But that priest wasn't an exception in communist Poland.

Solidarity brought together anti-government leftists and conservative Catholics alike, and got a big boost when John Paul II became pope in 1978.

Having a Pole at the head of the Vatican proved to be a powerful source of support, as he inspired thousands in sermons about hardship and freedom.

Wojtowicz's son was later caught and arrested at his factory job. His weeks in jail proved agonizing to his family as relatives were never told how the jailed activists were doing, or when they would be released.

Wojtowicz went to see her son in the city of Kielce, taking advantage of the right to travel granted to the elderly.

"I went and the streets were empty. Everything was quiet," she said. "There were only military vehicles out. I went, but they wouldn't let me see him."

Martial law lasted more than a year. Thousands were arrested and some 100 were killed as military vehicles patrolled the streets and enforced curfews.

Solidarity was banned and Lech Walesa was detained and incarcerated at a country home near the Soviet border.

But the crackdown ultimately failed to stifle Solidarity.

In 1989, amid a crumbling economy and food shortages, the government was forced to negotiate for power with the trade union.

The so-called Round Table Talks paved the way to Poland's first democratic post-war elections, and convinced others in the Soviet bloc that a bloodless revolution was possible.

When Walesa ran for president in 1990, however, many were still afraid to voice their support for the movement that had spent so many years underground.

In Szydlowiec, shopkeepers were reluctant to hang election posters in their windows, Wojtowicz said, even as a group of Solidarity supporters openly carried leaflets promoting Walesa.

"They told me, 'you'll help us,'" said the retired merchant. "They knew I was Solidarity."

|

|

|

|

Post by valpomike on Mar 30, 2009 2:25:38 GMT 1

This took the work of many, many people, who wanted and got a free Poland.

This took to long to come around.

Mike

|

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Apr 13, 2009 18:23:53 GMT 1

Compensations for Victims of Anti-Communist ProtestsPrzemyslaw Jedlecki, Katowice

Gazeta Wyborcza

2009-04-03

Relatives of people who lost their lives fighting communism in the years 1956-1983 will receive compensations. Parliament has just passed a bill granting them PLN50,000 each.

'Better late than never', says Krzysztof Pluszczyk, head of a civic committee in memory of fallen miners.

The families of miners killed in 1981 have long waited for a gesture from the government. Two years ago the Katowice District Court sentenced 15 members of a special riot police platoon for their involvement in the pacification of the Wujek and Manifest Lipcowy mines, ruling that it was a communist crime. Soon thereafter the Interior Ministry announced that the victims' families would receive compensations. But it remained unclear when and how large. The pledge was repeated in December 2007, during celebrations of the pacification' s 26th anniversary, by Deputy Prime Minister Waldemar Pawlak. Finally, a draft act was drawn up by the Silesian provincial office and then by the Interior Ministry. Yesterday, the latter was unanimously passed by the Sejm.

The law provides for the payment of compensations to the families of the victims of anti-regime protests from the years 1956-1983. Eligible to apply will be the relatives of whose who lost their lives during the protests in June 1956 in Poznañ, October 1957 in Warsaw, December 1970 in Gdañsk, Szczecin and other cities in northern Poland, June 1976 in Radom, and during the martial law - especially of the miners killed at the Wujek mine in 1981. According to the National Remembrance Institute, some 135 people were killed during those protests. The compensations can thus run up to some PLN27 million. The relatives will have two years from the act's coming into force to submit applications.

Grzegorz Dolniak, deputy leader of the Civic Platform (PO)N caucus, said that by passing the law, the state fulfilled its duty to those who lost their lives fighting communism.

'These people wanted a free Poland. I know the families' financial expectations may be greater than this, but the act doesn't prevent them from seeking compensations in civil courts', says Mr Dolniak.

He adds that each family member will receive PLN50,000, and if someone dies after applying, the right to compensation will be inheritable.

But Stanis³aw P³atek, one of the leaders of the strike at Wujek, is not satisfied:

'The mountain gave birth to a mouse. I know there was talk earlier of higher figures. This is certainly not going to satisfy the families' expectations' .

Krzysztof Pluszczyk agrees: 'On the other hand, it's a light in the tunnel. For so many years no one in the government wanted to help these people. It's better late than never, though the figures are modest.'

He stresses that not all relatives of the dead miners have lived to see this moment. He does not rule it out that in this situation, and unlike last year, government officials will be invited to take part in the anniversary celebrations:

'We didn't invite them, because we didn't want to hear more empty promises. Now they can expect to be invited.'

Katarzyna Kopczak-Zagórna, daughter of a miner killed at Wujek, is surprised to hear the news about the law just passed.

'I didn't know they had finally put this on the agenda. I'm very happy we'll finally receive some compensations at all.'

|

|

|

|

Post by valpomike on Apr 13, 2009 18:29:48 GMT 1

Great, I am sorry it took so long, and is it enough?

Mike

|

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Apr 13, 2009 22:47:19 GMT 1

Great, I am sorry it took so long, and is it enough?Mike Hmm, the article says each member of the bereft family will receive 50.000. If so, it`s a lot. But if the money is granted to the whole family, then it isn`t. Better late then never though I must admit I have sometimes doubts about such procedures. Taking money for the death of your relative is controvercial to me. Trading death.... ----------------------------------------------------- After great demonstrations of 1982-83 had finished and Popiełuszko`s death in 1984 had been mourned, the society fell a prey to apathy. People took care of their problems of everyday life, participated neither in regime`s nor opposition actions. In 1985-1988 it seemed that the dictators managed to pacify the nation. However, it was a wrong assumption. Life in communist Poland was getting more and more unbearable. Everybody knew that the system had to be changed because if continued, it would finally bring a complete disaster to the country. Having nothing to lose, frustrated workers and intelligentsia rose against communism again. In 1988 there were two giant waves of strikes at steel plants, shipyards, mines and universities. Spring strikes were brutally supressed by system`s forces like before (luckily without shooting) but after the summer wave the regime finally realised they needed to start talking with people to avoid the revolution by angry and hungry masses. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1988_Polish_strikesThe 1988 Polish strikes were a massive wave of strikes which broke out in 1988 in the People’s Republic of Poland. The strikes, as well as street demonstrations, continued well into summer, with last of them ending in early September. These actions shook the Communist regime of the country to such an extent, that it was forced to begin talking about recognising Solidarity[1]. As a result, later that year, the regime decided to negotiate with the opposition[2], which opened way for the 1989 Round Table Agreement. It must be mentioned that the second, much bigger wave of strikes (August 1988) surprised both the government, and top leaders of Solidarity, who were not expecting actions of such intensity. These strikes were mostly organized by local activists, who had no idea that their leaders from Warsaw had already started secret negotiations with the Communists[3].Background

Late 1980s was the time of deep economic crisis of Poland. The military regime of General Wojciech Jaruzelski (see Martial Law in Poland) did not carry out a radical reform of the economy in 1982-1983, industrial production remained below the 1979 level, average inflation rate climbed to 60% by 1988, and Poland’s hard-currency debt to the Western countries grew from $25 billion in 1981 to $43 billion in 1989[4]. Furthermore, the military rule was a failure, and Solidarity had been outlawed in 1982, which forced its members to go underground. In those circumstances, anger and frustration of the nation grew, deepened by economic malaise, and lowering living standards. More than 60% of population lived in poverty, and inflation, measured by black-market rate of the U.S. dollar, was 1,500% in the period 1982 - 1987[5].

On November 29, 1987, the Comunists, who did not know how to deal with the crisis, decided to seek popular support for a 110% price increase, calling the Referendum on political and economic reforms (see Referendums in Poland). The government of Zbigniew Messner lost - officially, 63.8% voters participated in it, but according to independent sources, the turnout was around 30%[6]. Nevertheless, deputy prime minister Zdzislaw Sadowski decided to go on with the price increase. It was introduced on February 1, 1988, and it was the biggest hike since 1982. This operation was a failure, as the price increases were followed by 40% increase in wages, which was supposed to offset the price increases. As a result, inflation rose at alarming speed, and by late 1989, near hyperinflation was reached[7].

[edit] Repressions against the Solidarity movement

In late 1987, Communist authorities initiated a wave of repressions of activists of underground Solidarity trade union and other oppositional organizations. On November 9, Kornel Morawiecki, leader of Fighting Solidarity was arrested. In the same year, Lech Wałęsa resumed his post as leader of Solidarity, where he remained until 1990[8]. Meanwhile, local branches of the movement tried to legalize themselves in courts across Poland, but all these attempts were refused. On August 31, 1987, the 7th anniversary of the Gdańsk Agreement, street demonstrations and clashes with police took place in Warsaw, Wrocław, Lublin, and Bydgoszcz[9]. On March 8, 1988, on the 20th anniversary of the 1968 Polish political crisis, activists of the Independent Students Union organized demonstrations in Warsaw, Kraków and Lublin. Most active demonstrators were immediately repressed by the government.

Spring 1988 strikes

On April 21, 1988, 5000 workers of Stalowa Wola Steelworks organized a meeting, during which they demanded end of repressions of Solidarity activists, and 20,000 złoty salary increase[10]. First strikes broke out four days later, on April 25, 1988, in mass transportation centers in northern cities of Bydgoszcz[11] and Inowrocław. On the next day, one of the biggest companies of the country, Vladimir Lenin Steelworks in Kraków, joined the strike. The workers demanded salary increase, re-employment of Solidarity activists, who had been fired during the martial law, as well as legalization of Solidarity[12]. Meanwhile, a strike broke out in Stalowa Wola Steelworks. Both these actions were suppressed by the Communist security forces (ZOMO), suported by anti-terrorist units. In Stalowa Wola, a demonstration of force, together with threats of use of regular army troops, was sufficient, and the strikers gave up on April 30. In Krakow, however, the workers continued their action, therefore the government decided to use power. In the night of May 4/5, the steelworks were brutallly pacified by the ZOMO and anti-terrorist units[13]. In reaction to the attack, workers of several factories across the country organized protests and meetings.

On May 1, 1988, opposition activists organized peaceful demonstrations in several Polish cities, such as Bielsko-Biała, Dąbrowa Górnicza, Gdańsk, Kraków, Łódź, Płock, Poznań, Warsaw, and Wrocław. They were attended by thousands of people, and in some places, street fights erupted. On the next day, a strike broke out in Lenin Gdańsk Shipyard, where workers demanded legalization of Solidarity. Soon, Tadeusz Mazowiecki and Andrzej Wielowieyski showed up in Gdańsk, ready to talk to the management of the plant. However, the talks were fruitless, and on May 10, after threats of use of force, the strike ended in the atmosphere of failure[14]. The last strike of the spring took place in Szczecin, involving workers of city’s mass transit system.

Summer 1988 strikes

During late spring and early summer of 1988, the situation in Poland did not improve. In several cities, local Solidarity branches unsuccesfully tried to legalize the union. On June 19, local elections took place, and Solidarity urged voters to boycott them. On July 26, government spokesman Jerzy Urban said that Solidarity permanently belonged to the past, and two days later, Polish sociologists announced that only 28% of Poles believed that government’s reforms would succeed. Most people thought that the reforms would end up with even deeper crisis[15]. The first strike of summer 1988 took place in the Upper Silesian city of Jastrzębie-Zdrój, and it began on August 15.

Upper Silesia

On August 15, a strike broke out at the July Manifesto coal mine in Jastrzębie-Zdrój; the mine had been a center of strikes eight years earlier (see Jastrzębie-Zdrój 1980 strikes). Importantly, miners from July Manifesto tried to start a strike on May 15, 1988, but the main activists of Solidarity had been arrested by the Security Service, whose agents got word of the plans[16]. In the second half of August, further mines, most from southern Upper Silesia joined the strikers, and the Interfactory Strike Committee under Krzysztof Zakrzewski was founded in Jastrzębie-Zdrój. Miners from Jastrzębie were supported by a local priest, reverend Bernard Czernecki.

Among the striking mines were:

* Borynia from Jastrzębie-Zdrój,

* Jastrzębie from Jastrzębie-Zdrój,

* Moszczenica from Jastrzębie,

* ZMP from Zory,

* Krupinski from Zory,

* XXX-lecia PRL from Pawlowice,

* 1 Maja from Wodzisław Śląski,

* Marcel from Wodzisław Śląski,

* Morcinek from Kaczyce,

* Andaluzja from Piekary Śląskie,

* Lenin from Mysłowice[17].

Communist secret services, as well as Solidarity leaders, were completely surprised by the strikes in Upper Silesia. In a report dated August 14, 1988, agents of Security Service wrote: “According to our sources, opposition leaders are not planning anything” [18]. Later, some of the strikes were broken by the special forces - at Morcinek in Kaczyce (August 24), Lenin in Myslowice, and Andaluzja in Piekary. Almost all strikes took place in mines, whose employees were people transferred from other areas of Poland in the 1970s. Mines in “traditional” parts of Upper Silesia did not join the protestors, except for Andaluzja from Piekary Slaskie, and Lenin from Myslowice.

On September 2, Lech Wałęsa appeared in the July Manifesto mine, the last place that continued the strike. After his appeal, and a long argument, the miners decided to give up. The strike at July Manifesto was the longest one of Communist Poland[19].

Szczecin

On August 17, the Port of Szczecin began to strike. In the following days, other companies from Szczecin stopped working, and the Interfactory Strike Committee was founded. It issued a statement, which consisted of four points, one of which was the demand of legalization of Solidarity. On August 28, the Committee announced that Wałęsa was its sole representative. In response, Wałęsa sent to Szczecin a statement about his meeting with Czesław Kiszczak, during which the future Round Table talks had been discussed. Nevertheless, the strikes in Szczecin did not end until September 3. Wałęsa had informed the public about talks with the regime during the August 21 demonstration in Gdańsk[20].

Stalowa Wola

By far the biggest strike of summer 1988 took place in Stalowa Wola Steelworks, in which around 10,000 workers participated, and the plant was surrounded by militarized police units[21]. The Stalowa Wola strike was so significant, that it was dubbed “the fourth nail in the coffin of Communism”[22].

Since the Steelworks was an arms manufacturer, the factory, which in the 1980s employed around 21,000 people, was under a watchful eye of the security services, and its employees were strictly prohibited from undertaking any kind of oppositional activities. Nevertheless, across the 1980s, it was one of main centers of protests and demonstrations, and in spring of 1988, Stalowa Wola workers started the first strike of that year, which ended after a few days, and which was a prelude of the summer events. On August 22 in the morning, workers of the plant decided to organize a sit-in, with only one demand - legalization of Solidarity[23]. This decision was crucial for further events in Poland, as strikes in Upper Silesia were slowly coming to an end. Led by Wieslaw Wojtas, the strike lasted 11 days. Workers were supported by local priests, and activists of the so-called Supporting Office, who delivered food, medicine, blankets, helped those beaten by government security forces, but also informed Western Europe about situation in Stalowa Wola. Every day, citizens of the town gathered by the Gate 3 to the steelworks, where local parish priest, reverend Edmund Frankowski, celebrated two masses (August 26, and 31), which were attended by up to 10 000 people[24]. Frankowski actively supported the strikers, in the sermons, he urged the faithful to help the workers.

The Stalowa Wola strike ended on September 1, after the personal request of Lech Wałęsa, who called Wiesław Wojtas, telling him: “You are great, but please, end the strike, I am asking you in the name of Solidarity”[25]. Following Wałęsa's request, 4 000 workers left the factory on September 1, at 7 p.m. Together with around 15 000 inhabitants of the city, they marched to the Church of Mary, Queen of Poland, where they were greeted by reverend Frankowski, who said: “Illegal priest is welcoming participants of the illegal strike”[26].

[edit] Gdańsk

On August 19, a group of young activists began circulating leaflets, urging workers of the Gdańsk Lenin Shipyard to join striking miners from Jastrzębie-Zdrój. According to Alojzy Szablewski, who was leader of plant’s Solidarity, Lech Wałęsa was called, and during a meeting it was decided the strike would begin on Monday, August 22[27]. On that day, at 7 a.m., some 3000 workers put away their tools. Their only demand was short - legalization of Solidarity.

Soon afterwards, other main factories of Gdańsk joined the shipyard - Port Polnocny, Stocznia Polnocna, Stocznia Remontowa. Interfactory Strike Committee was founded, led by Jacek Merkel, and workers were supported by a number of personalities, such as Jacek Kuroń, Adam Michnik, Lech Kaczyński, and his twin brother Jarosław Kaczyński. Unlike in August 1980, the 1988 strike was different, as the government lacked power to force the strikers to give up. Furthermore, Gdańsk Lenin Shipyard was visited by a number of guests from abroad, including Boston Mayor Ray Flynn, in whose presence the use of force was not likely. The events in Gdańsk were described by Padraic Kenney as truly Orange Alternative strike. Workers of the Gdańsk Repair Shipyard mocked secret service and police agents, by making a styrofoam tank with the slogan: Leave your arms at the gate, we want dialogue[28].

The strikes in Gdańsk ended on September 1, and on September 3, both sides signed an agreement, according to which the communists promised not to persecute the strikers. The promise was broken, and hundreds of people were fired in the fall of 1988.

Outcome

At first, the government tried to threaten the protestors; on August 20, the Committee of National Defence announced preparations for introduction of national state of emergency. However, the determination of the workers made the Communist realize that talks with the officially non-existent trade union were inevitable. On August 31, General Czesław Kiszczak met with Lech Wałęsa. During the conversation, which was witnessed by Archbishop Bronisław Wacław Dąbrowski, Kiszczak appealed for putting an end to strikes, he also promised to take care of legalisation of Solidarity[29].

Even though Solidarity activists in several centers opposed Wałęsa's appeal to end strikes, soon afterwards laborers returned to work. The last strikes, in the Port of Szczecin and the July Manifesto coal mine, lasted until September 3. On December 18, Wałęsa established the Solidarity Citizens' Committee, which opened way for the Polish Round Table Agreement.Gdańsk Shipyard. Demands were always the same - bring back delegalised Solidarity trade union.    Shipyard workers! We are with you! Hold on!        Warsaw University. Students supported workers. Full solidarity.  Another wonderful example of solidarity - Belarussian students at Warsaw University joined the strike  Wrocław University  University in Łódź.   The end of spring strikes - workers are leaving their plants.   Kaczyński brothers on the right  Some spring strikes were suppressed by the police.  Strikes started again in August. Walesa  Desperate workers  Public transport on strike   A mass in a striking steel plant in Krakow.    Most priests actively supported Solidarity.  Mine   wyborcza.pl/5 wyborcza.pl/5,75478,3784566.html?i=4 The policy of brutal pacification used by the regime in previous years failed. Here is a photo of a tank which took part in introducing martial law in 1981. It has a Solidarity leaflet stuck on it.  It is an insightful omen of what happened in 1988 and later. |

|

|

|

Post by valpomike on Apr 14, 2009 3:45:03 GMT 1

Us here in the U.S.A., I think, but hope not, could have our own civil war, any day, since they are giving away ever thing.

Mike

|

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Apr 15, 2009 12:11:23 GMT 1

Us here in the U.S.A., I think, but hope not, could have our own civil war, any day, since they are giving away ever thing. Mike People deserve decent life in America, paradise must go on, giving away is fine. ------------------------------------------------------------------ Poles mark 20 years since talks toppled communism

Feb 4, 2009

WARSAW (AFP) — Twenty years after Poland's ruling communist party and the Solidarity freedom movement sat down for watershed talks, participants in the historic negotiations are recalling how they sped the collapse of the entire Soviet bloc.

February 6, 1989 marked the launch of the so-called Round Table negotiations, which came after years of struggle between the regime and Solidarity, born in a strike-wave in 1980 and forced underground by a military crackdown a year later.

The negotiations paved the way to semi-democratic elections in June 1989, a vote which saw Solidarity, led by the iconic Lech Walesa, break the power monopoly of the communist regime by entering parliament.

"Was there any real alternative to this great bloodless victory?" Walesa, 65, asked rhetorically in an interview this week.

"Without the Round Table, communism could have stuck around for another fifty years and a day," he said.

Two decades later, negotiators still marvel at the pace of change sparked by the talks.

"No one on either side thought events would move so quickly and that six months later my government would see the light of day," Tadeusz Mazowiecki, 81, a Solidarity intellectual who became post-war Poland's first non-communist prime minister in 1989, told AFP.

"All we hoped for from those negotiations at the most was the legalisation of Solidarity, seven years after it was banned by the communists, and that Lech Walesa not be treated as just a private person," Mazowiecki said.

The communist regime had refused to recognise Walesa as leader of the Solidarity union, banned in 1981.

The communist regime was also amazed, recalled Leszek Miller, at the time a communist negotiator.

"I thought it would be a step towards democracy and that Solidarity would take on the role of the opposition, certainly not the role of government straight away," said Miller, 62, who himself became premier when the ex-communist Social Democrats won office in 2001.

"Solidarity got much, much more than it had demanded," he claimed.

After two months of talks, the Round Table yielded a complex electoral accord allowing Solidarity to run for 161 of the 460 seats in Poland's lower house and all 100 in the Senate.

In the June 4 election, Solidarity won every seat it was allotted by huge margins, while the communist side was forced into embarrassing run-offs.

"Even hard line communists voted for Solidarity candidates -- the will for change was widespread," said Jerzy Urban, once the communist regime's media spin doctor who thwarted press freedom, now the publisher of "Nie" (No), a biting satirical weekly.

Incapable of forming a government, the communists ceded the initiative to Mazowiecki, insisting he include a few party members as ministers.

"We could have easily falsified the election results, but we recognised them," Urban told AFP.

Communism still held sway elsewhere -- the Berlin Wall did not fall until November 1989, and the Soviet Union only collapsed in 1991.

"Nothing was set in stone. Hard-line communists were still very strong. (Romania's communist dictator Nicolae) Ceausescu had proposed military intervention to help the communists recapture power in Poland and there was the Yanayev putsch against (Soviet leader Mikhail) Gorbachev in 1991," said Mazowiecki.

Mazowiecki also had to retain regime leader General Wojciech Jaruzelski as head of state, before he stepped aside and Walesa was elected president, serving from 1990 to 1995.

Although the communist regime effectively gave up power after the Round Table, the deal paved the way for communists revamped as Social Democrats to win parliamentary elections in Poland in 1993.

Communist negotiator Aleksander Kwasniewski went on to become a two-term president, winning elections in 1995 and 2005.

During his tenure Poland cemented its place among western democracies, joining NATO in 1999 and the European Union in 2004.

After Poland's regime fell, Mazowiecki faced criticism for drawing what he called a "thick line" under the past, a strategy he claimed was necessary to coax the communists out of power.

Twenty years after the Round Table accords, however, Jaruzelski, 85, and members of his entourage are now on trial over their regime's record.Walesa meets general Kiszczak, Interior Minister, the one who introduced martial law.  Walesa meets general Jaruzelski    The talks     In the center - young comunist Kwaśniewski. In 1990s he will become a president.         Happy opposition leaders with happy communists.       Parties. Everybody was glad that they were able to have peaceful discussion instead of civil war.

Two decades past Poland's 'compromise'

By JAN SKORZYNSKI

The Japan Times

4/5/09

WARSAW — "Poland — ten years, Hungary — ten months, East Germany — ten weeks, Czechoslovakia — ten days."

So chirped many in Prague in November 1989, reflecting the pride and the joy of the Velvet Revolution, but also the sustained effort that was needed to end communism, whose demise began in Warsaw the previous February.

Indeed, communism's breakdown had begun 10 years earlier in Poland during Pope John Paul II's first pilgrimage to his homeland, a visit that shook communist rule to its foundation. Within a year, Polish workers were striking for the right to establish independent trade unions, staging two weeks of sit-ins at state-owned factories to achieve their goal. Karl Marx would have been proud of them, but it was the pope's portrait that hung on the gate of Gdansk's Lenin Shipyard during the strike.

The Solidarity union that was born in 1980 broke the Communist Party's monopoly on power. The movement united 10 million people: workers and professors, peasants and students, priests and freethinkers among them — all of civil society. This infant democracy was harshly interrupted when martial law was imposed in December 1981, with Solidarity outlawed and dissidents arrested. But this totalitarian blitzkrieg could not last. Democracy did not die; it merely went underground.

For the next seven years, Solidarity fought for re-legalization, building the biggest underground network of resistance Europe had seen since Hitler's war. But this was nonviolent resistance. Its main weapon was the language of freedom. In the mid-1980s, there were about 1,000 independent, uncensored journals in Poland. They represented a full range of ideas and editorial styles — from factory leaflets and bulletins to intellectual magazines. Hundreds of books prohibited by Communist censors (for example, Gunther Grass' "The Tin Drum") came to light.

Solidarity's leader, Lech Walesa, did not surrender in prison and retained his national esteem. With the economy in steep decline, Poland's rulers began to seek to stabilize the political system and re-establish relations with the West. In 1986, the government released political prisoners — a precondition for talks with the opposition. But it took the Communists two more years to realize that they could not introduce economic reform without Solidarity's assent.

So talks began.

The reason the talks were possible was that the opposition's goal was not the violent overthrow of party rule. Instead, its democratic goals were to be fulfilled by a compromise with the authorities. Walesa and his closest advisers — Bronislaw Geremek and Tadeusz Mazowiecki — pushed this moderate policy, demanding liberation while recognizing the political reality of Soviet domination.

Two waves of strikes in 1988 forced Gen. Wojciech Jaruzelski's government to negotiate with Solidarity, which, after a few months of hedging, was legalized. The "Roundtable" talks to change the political system could begin. The haggling continued from February until April 1989. The main issues were legalization of the opposition, partially free elections, and creating the office of president to replace the Communist Party chief. The Communists were guaranteed a majority in Parliament. While the election to the newly created Senate was entirely free, the opposition could compete for only one-third of the seats in the Lower House.

But the key point was that the party's monopoly on power was jettisoned. Solidarity gained the opportunity to create independent media and a grassroots political organization. Finally, the Communists agreed that the elections to be held in four years would be entirely free. The road to democracy was open.

But the dictatorship' s end came sooner then anyone expected. In June 1989, the opposition won the parliamentary election in a landslide. It was impossible to form a government without its participation. Jaruzelski was elected president, but he had to accept the new division of power. The decisive political maneuver — building a coalition with allies of Communists — was carried out by Lech Walesa. A Solidarity representative, Tadeusz Mazowiecki, became prime minister.

In September 1989, Poland had the first government ever led by democratic parties in the Soviet bloc. It was a revolution, but with a difference: the political system changed without a body count. This was due, above all, to Solidarity's prudent policy. But it was civic activity — resistance movements, strikes and other manifestations of social support — that buttressed Solidarity.

Mikhail Gorbachev's nonintervention policy toward Eastern Europe meant that Soviet tanks would not annul the changes, as they had done with the Prague Spring.

The Polish Communists did not intend to build democracy; their plan was to absorb moderate opposition groups into a partially modified political system. Handing over power to Solidarity was the last thing they had in mind. Yet the Roundtable compromise turned out to be good even for them, as Communist "reformers" began to build new careers in business and politics (one, Aleksander Kwasniewski, became Poland's second democratically elected president).

The Roundtable also provided the Communists with a sense of safety that diminished their fear of democratic change. A hangman's noose did not await them. This was an important sign for Poland's neighbors in the Soviet bloc, which took its example to heart.

In a few months, talks between communist bosses and their democratic opponents (often in the form of a roundtable) paved the way to free elections and new democratic governments in Budapest, Prague, East Berlin and Sofia.

By 1989's end, post-Yalta Europe was free. Since then, the symbol of the great revolution of 1989 has been the fall of the Berlin Wall. But the Roundtable talks in Warsaw 20 years ago this month is where the Iron Curtain began to be dismantled.

Jan Skorzynski, a former deputy editor in chief of Rzeczpospolita, is the author of several books on the history of the Polish democratic opposition to communism and the Solidarity movement. His new book, "The Roundtable Revolution," will be published this month. © 2009 Project Syndicate/Institute for Human Sciences (www.project- syndicate. org) |

|

|

|

Post by valpomike on Apr 15, 2009 23:13:33 GMT 1

Only if all share, and now we don't, we pay the tax, they get the benefits.

Mike

|

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on May 10, 2009 22:17:30 GMT 1

Gdansk's fall of communism celebrations cancelled?

thenews.pl

05.05.2009

Celebrations to mark the end of communism in Poland, planned for 4 June at the historic Gdansk shipyard, will probably be cancelled, PM Donald Tusk said today.

He is afraid that the 20th anniversary of the first free election in the communist bloc will be spoiled by the Solidarity trade union's protests over the recent ruling by the European Commission which threa tens thousands of jobs at the yard.

"I will not expose Poland's image abroad to a scandal," Tusk said.

Recently the trade union leaders declared that they plan a demonstration to protect the Gdansk shipyard and its work places while the celebrations are taking place..

"We are not against the celebrations but they should take place somewhere else," Karol Guzikiewicz, said deputy leader of the Solidarity chapter at the yard.

Prime Minister Tusk claimed that he is ready to find a different place for the celebrations, but the Gdansk local authorities disagree. Yesterday, the president of Gdansk was trying to convince the trade unionists to change their plans and not disrupt any celebrations.

"On June 4 we have a fantastic opportunity to remind the world about the role of Gdansk and Poland in the fall of communism. It is our unique chance for promotion in Europe and our five minutes in history," Pawel Adamowicz said.

Legendary former leader of Solidarity, Lech Walesa, supports Tusk's idea to cancel Gdansk's celebrations.

Poland's parliamentary election on 4 June 1989 marked the beginning of the collapse of communism.

|

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on May 23, 2009 21:18:40 GMT 1

Poland Blasts EU Video Clip on End of Communism

Politicians said the clip `1989-2009: 20 years of Liberty`, produced by the European Commission focused too much on Germany.

Javno.com

May 18, 2009

Poland criticised a European Union video clip commemorating the fall of communism in 1989, saying it underestimated the country's role in the event.

Politicians said the clip "1989-2009: 20 years of Liberty", produced by the European Commission focused too much on Germany without mentioning the achievements of Poland, the EU's biggest ex-communist country.

Poland's ambassador to the EU, Jan Tombinski, said the clip could sour the public mood towards the EU ahead of the European Parliament election in June.

On Monday, Tombinski wrote to the EU's communication policy chief Margot Wallstrom to demand changes in the clip, available on the Commission's website (www.europa. eu).

"The simplistic vision presented in the clip may instead introduce needless controversies which should be avoided during the European elections campaign," the letter said.

The clip is part of an EU campaign to commemorate the 20th anniversary of the fall of communism in central and eastern Europe, where most countries now belong to the EU.

Analysts say the debate on the clip could give ammunition to Eurosceptics in the campaign to the European election against pro-EU, right-centre government of Prime Minister Donald Tusk.

The Commission rejected the criticism, although it promised it would correct one inaccuracy in the clip.

It is quite an artistic video clip. This is not a historical programme, this is not a documentary, " a Commission spokesman said.