|

|

Post by Bonobo on Jul 3, 2009 18:42:21 GMT 1

Tadeusz Kosciuszko  A Two-Country Freedom Fighter A Two-Country Freedom Fighter

By ARAM BAKSHIAN JR.

The Wall Street Journal

6/20/09

When the great African-American educator and human-rights pioneer Booker T. Washington visited Krakow, Poland, in 1910, he made a special point of paying tribute to a dead white male with the nigh-unpronounceabl e name of Tadeusz Andrzej Bonawentura Kosciuszko.

"I knew from my school history what Kosciuszko had done for America in its early struggle for independence, " Washington would later write. "I did not know, however, until my attention was called to it in Krakow, what Kosciuszko had done for the freedom and education of my own people. . . . When I visited the tomb of Kosciuszko, I placed a rose on it in the name of my race."

In his views on race, as in so many other matters, Tadeusz (Thaddeus in English) Kosciuszko (1746-1811) was a man ahead of his time. A freedom fighter on two continents, he did not hesitate to denounce the evils of slavery while playing a crucial role as chief engineer in America's fledgling Continental Army. In his native Poland, he appealed to the patriotism of the privileged classes as he championed full civil rights for the disenfranchised majority of Poland's peasants, Jews and city-dwelling commoners. But he also upheld the rule of law and opposed mob violence. He was, in the words of French historian Jules Michelet, "the last knight, but the first citizen in Slavic lands with a modern understanding of brotherhood and equality."

Despite his heroic efforts, Kosciuszko's fatherland had to wait a century after his death before regaining independence from Russia. The world would have to wait even longer for an accessible, soundly researched, English-language biography. With "The Peasant Prince," Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Alex Storozynski has filled the void.

0

Book Details

The Peasant Prince

By Alex Storozynski

Thomas Dunne, 370 pages, $29.95

And what a tale he has to tell. A melodramatic, foiled elopement deprived the young Kosciuszko of the love of his life and led him to cross the Atlantic and sign up with George Washington's ragtag rebel army. The Polish émigré engineered the network of fortifications around West Point that Benedict Arnold unsuccessfully tried to betray to the British and that helped keep the main British army bottled up in New York City. Kosciuszko also played a key role in the wilderness campaigns that ended in the crucial American victory at Saratoga. And he made a triumphal return to his native Poland in time to lead a doomed but heroic national struggle against Russia and overwhelming odds.

All this and a supporting cast that amounts to a Who's Who of 18th-century American and European history. In America, those who knew Kosciuszko included Benjamin Franklin (who helped recruit him); George Washington (who had trouble getting Kosciuszko's name right but hailed him as a military "engineer of eminence"); Thomas Jefferson (who called him "as pure a son of liberty as I have ever known"); and Thomas Paine (who, like Kosciuszko, was granted honorary French citizenship by the revolutionary regime but spoke out against its brutal excesses). In Europe, Kosciuszko's acquaintances included Napoleon Bonaparte (who tried—and failed—to use him as a pawn in European power politics) and Catherine the Great (who, after ruthlessly suppressing the Polish insurrection, kept Kosciuszko a political prisoner in Russia until her death in 1796).

Mr. Storozynski painstakingly provides context and ample documentation for this remarkable story, although he occasionally missteps: Prussia was not yet a "Kingdom" in 1683, muskets are not rifles, military turrets are not "minarets," and the guillotine, far from being "new" at the execution of Louis XVI in 1793, had been used for a least a year to separate common criminals from their heads.

But the virtues of "The Peasant Prince" far outweigh its few sins against fact. Mr. Storozynski does a particularly good job of explaining the topsy-turvy nature of 18th- century Poland, a decayed feudal "Royal Republic" headed by an elected king—the charming, well-intentioned but terminally spineless Stanislaw Augustus Poniatowski. He was a bon vivant, patron of the arts and involuntarily retired lover of Catherine the Great—but dominated by a venal, arrogant handful of wealthy aristocratic families. Between them and the Polish masses stood the lesser gentry—the traditional backbone of Poland's army, the bulk of the nation's severely limited "electorate" and the class from which Kosciuszko himself was sprung.

Even as Poland's stronger neighbors began nibbling at her borders, a national awakening in the spirit of the 18th-century Enlightenment resulted in a burst of intellectual life and educational reform in Poland during Kosciuszko's childhood. One result was that, as the bright younger son of a minor landowner, he was chosen to attend the Royal Knight's School, the newly established military academy in Warsaw where he received a first-class education, enhanced by his studying art and engineering in Paris.

Kosciuszko's later combat experience in America—and his social observations there— helped him to create the first truly national Polish army, incorporating volunteers from the burgher class, thousands of serfs and peasants armed only with scythes, and even a Jewish cavalry regiment that may have been the first purely Jewish military formation since biblical times. Under his inspiring leadership, these disparate elements combined with patriotic members of the clergy and aristocracy to form the first mass nationalist movement in central and eastern Europe. That it was eventually crushed by the first—but not the last—cynical Berlin-Moscow alliance was no wonder. That Kosciuszko was able to score several impressive victories before being crushed by overwhelming force was miraculous.

Once released from czarist imprisonment, the battle-scarred Polish paladin led a mostly anticlimactic life in exile. He refused to be taken in by Napoleon, who, Kosciuszko rightly predicted, "will not resurrect Poland—he thinks only of himself. He detests every great nation and especially the spirit of independence. He's a despot, and his only aim is personal ambition. He will not create anything durable." But Kosciuszkoalso failed to persuade the allied powers at the Congress of Vienna to honor Poland's right to national existence. His last years were spent in Swiss exile, a modest, kindly old soldier.

Kosciuszko's will included a provision that some of his fortune should be used to buy the freedom of American slaves and to pay for their education. The scheme, audiacious for its time, seemed to unnerve Thomas Jefferson, the executor, who feared that the fragile new country was unprepared for such a step toward universal liberty. Jefferson recused himself as executor and, alas, Kosciuszko's estate was never used as he had hoped.

Were he with us today, Kosciuszko would probably be more amused than annoyed by the fact that many Americans know his name only as a brand of mustard (with out the "z"). Or they might be familiar with Kosciuszko as the designation of a bridge linking Brooklyn and Queens in New York. The bridge, like the man, has served for the benefit of countless millions.       |

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Jul 8, 2009 21:07:38 GMT 1

Marie Sklodowska Curie named greatest woman scientist of all time

London, July 2 (ANI): Nobel Prize-winning nuclear physicist Marie Sklodowska Curie, who discovered that radiation therapy could treat cancer, has been voted the greatest woman scientist of all time.

The Polish-born researcher bagged over a quarter of the votes (25.1 per cent), almost double the votes received by her nearest rival Rosalind Franklin (14.2 per cent), the English biophysicist who helped discover the structure of DNA.Third on the list was Hypatia of Alexandria, played by Rachel Weisz in a recent film about the fourth century Egyptian philosopher.

New Scientist magazine conducted the poll of 800 scientists and members of the public, which was commissioned by cosmetics company L'Oreal.

At the fourth position was astrophysicist Dame Jocelyn Bell Burnell with 4.7 per cent votes.

London-born Ada, the Countess of Lovelace, the mathematician who wrote the first computer programmes grabbed the fifth spot in the poll.

Austrian physicist Lise Meitner who discovered nuclear fission was sixth in the list, while British chemist Dorothy Hodgkin who pioneered X-ray techniques was at seventh.

Then came French-born Sophie Germain, who was one of the world's greatest mathematicians, followed by American marine biologist Rachel Carson, who pioneered the global environmental movement ninth.

Standing proudly at the tenth spot is modern role model Dr Jane Goodall, the world famous primatologist, with 2.7 percent votes.

"The poll indicates the vital need to celebrate and raise awareness of the many female scientists who have shaped modern science since Marie Sklodowska Curie - and who are making a bigger contribution than ever," the Telegraph quoted Dr Roger Highfield, the editor of New Scientist magazine, as saying.

Grita Loebsack, of L'Oreal said: "Women are at the forefront of advances in many scientific disciplines, particularly in health and life sciences."

"The aim of the poll was to celebrate the contribution women have made to scientific research but also to highlight the lack of modern role models to encourage young women to pursue careers in science," she added.

The Top 10 woman scientists of all time are:

1. Marie Sklodowska Curie (25.1 percent)2. Rosalind Franklin (14.2 percent)3. Hypatia of Alexandria (9.4 percent)4. Dame Jocelyn Bell Burnell (4.7 percent)5. Ada, Countess of Lovelace (4.5 percent)6. Lise Meitner (4.4 per cent)7. Dorothy Hodgkin (3.8 percent)8. Sophie Germain (3.7 percent)9. Rachel Carson (3.3 percent)10. Dr Jane Goodall (2.7 percent) (ANI)

|

|

|

|

Post by valpomike on Jul 8, 2009 21:45:22 GMT 1

She is family, on my mother's side, I am told.

Mike

|

|

|

|

Post by tufta on Jul 8, 2009 21:51:48 GMT 1

She is family, on my mother's side, I am told. Mike Mike, I have to tell you something. There are no accounts of general Dąbrowski and Maria Skłodowska families being connected. It would have been a widely known fact if they were. Most probably you have been led astray by one of your ancestors who wanted to feel 'better'. This happens and is quite normal, but you don't need it. |

|

|

|

Post by valpomike on Jul 8, 2009 21:57:22 GMT 1

This is on my mother's side, like I said, she was a Roszkowski. Sorry you did not understand.

Mike

|

|

|

|

Post by tufta on Jul 8, 2009 22:05:53 GMT 1

This is on my mother's side, like I said, she was a Roszkowski. Sorry you did not understand. Mike Mike, please try to understand. No trace of Skłodowska and general Dąbrowsski families being connected. Please do overcome it. |

|

|

|

Post by valpomike on Jul 9, 2009 16:40:48 GMT 1

Remember there was no connection with the two, until my parents married around 1938. I did not say it was before this.

Mike

|

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Jul 20, 2009 14:38:01 GMT 1

Polish anti-Marxist thinker dies

By Adam Easton

BBC News, Warsaw

Leszek Kolakowski in 2003

Leszek Kolakowski was regarded as a leading anti-totalitarian writer

The Polish philosopher and historian of ideas, Leszek Kolakowski has died in hospital in Oxford, England. He was 81.

One of the few 20th Century eastern European thinkers to gain international renown, he spent almost half of his life in exile from his native country.

He argued that the cruelties of Stalinism were not an aberration, but the logical conclusion of Marxism.

MPs in Warsaw observed a minute's silence to remember his contribution to a free and democratic Poland.

Leszek Kolakowski was born in Radom, Poland, 12 years before the outbreak of the World War II.

Under the Nazi occupation of Poland school classes were banned so he taught himself foreign languages and literature.

He even systematically read through an incomplete encyclopaedia he found.

He once said he knew everything under the letters, A, D and E, but nothing about the Bs and the Cs.

After the war he studied philosophy and became a professor. Seeing the destruction wrought by the Nazis in Poland he joined the Communist Party.

But he gradually became disillusioned and more daring in his criticism of the system. In 1966 he was expelled from the party and two years later he lost his job.

Seeking exile in the West, he eventually settled at Oxford's All Souls college where he wrote his best-known work, the three-volume Main Currents of Marxism, considered by some to be one of the most important books on political theory of the 20th Century.

In the 1980s, from his base in Britain, he supported Poland's pro-democracy Solidarity movement which overthrew communism in 1989.

For many of its leaders he was an icon. |

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Aug 23, 2009 22:12:35 GMT 1

Vitamin' coined by Polish scientistLewiston (ME) Sun-Journal

Jul 04, 2004

The story behind the word "vitamin" actually begins in the late 19th century, when a new method of processing rice called "polishing" was invented. Polishing removed the germ of the rice grain. This appealing-looking white rice became the new staple for people all over Asia.

Shortly thereafter, an alarming rise in the number of deaths due to the disease beriberi was noted in the Dutch colonies in the East Indies. Scientists sent to investigate concluded that beriberi was caused by the lack of a substance previously provided in the diet by the whole rice grain.

Further beriberi research was carried on in a U.S. lab by a Polish-born scientist named Casimir Funk. Based on the mistaken belief that the "anti-beriberi" substance was a specific type of organic compound called an amine, in 1912 he proposed the name "vitamine," combining "amine" with "vita," the Latin word for "life." The new term was intended to include the range of substances that were by then known to be essential in preventing the diseases beriberi, scurvy and rickets.

Up until then, these substances had been designated "accessory food factors." We're not sure what inspired Funk to coin the far catchier "vitamine," but his word was open to criticism among scientists, primarily because, though the chemical nature of the substances was still far from being fully understood, ultimately there was nothing to indicate that they were amines.

The matter was finally settled when it was proposed that the "e" be dropped, and that "-in" be considered an acceptable ending for a "neutral substance of undefined composition. " At the same time, the suggestion was made that the already-known substances called fat-soluble A, water-soluble B and water-soluble C be called simply Vitamins A, B, and C. By 1922 both the American and English Chemical Societies had voted to officially adopt the spelling "vitamin." (The "-ine" spelling continued to occur intermittently for another dozen years or so before it mostly fizzled out.)

It was in the 1920s, also, that the discoveries and the word finally reached a widespread public. Early advertisers actually had a bit of problem with the scientific sound of "vitamin," but nonetheless, they jumped on the bandwagon with slogans such as "Snider's catsup is made from the richest vitamin food."

Vitamins continued to be named alphabetically through Vitamin H (biotin), which was named in 1935. That same year, the sequential pattern was broken by Danish scientists with the naming of Vitamin K from their word "koagulation, " due to the substance's property of aiding in coagulation of blood.

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Casimir_FunkKazimierz Funk (February 23, 1884 – November 20, 1967), commonly anglicized as Casimir Funk, was a Polish biochemist, generally credited with the first formulation of the concept of Vitamins in 1912 , which he called vital amines or vitamines.

|

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Aug 24, 2009 13:11:26 GMT 1

Pulaski's namesake could get citizenship

The namesake of the town and county would be the sixth so-honored by the U.S.

By Amy Matzke-Fawcett

Roanoke (VA) Times

8/1/09

A U.S. House subcommittee has passed a resolution stating what Pulaski County residents have always known: Casimir Pulaski is a big deal.

The county and town's namesake, a Polish citizen who died from wounds sustained while fighting in the American Revolution in 1779, is the subject of a joint resolution conferring honorary citizenship.

Pulaski's first skirmish with the British was on Sept. 11, 1777, at the Battle of Brandywine. There, history says, he helped the colonists avoid defeat and saved the life of Gen. George Washington.

Pulaski died Oct. 11, 1779, after he sustained injuries fighting near Savannah, Ga.

If passed by both houses of Congress and signed by the president, Pulaski would be only the sixth person named an honorary American citizen. Others include British prime minister Winston Churchill in 1963; Raoul Wallenberg, who worked to free Jews from German concentration camps in World War II, in 1981; Pennsylvania proprietors William and Hannah Callowhill Penn in 1984; humanitarian Agnes Gonxha Bojaxhiu, better known as Mother Teresa, in 1996; and French Revolutionary War fighter Marquis de Lafayette in 2002.

"I think it's interesting and fascinating, " said Jeff Worrell, mayor of Pulaski. "I think it will interest a lot of people."

There was a Count Pulaski Day celebrated in years past, but the celebration has changed to become known as PulaskiFest, he said.

"He didn't have to come over to the colonies to fight, but he chose to leave his homeland for the cause of freedom and die for the cause of freedom," said town councilman Morgan Welker in an e-mail.

"I'm sure the citizens of Pulaski will join others from across the country who share Count Pulaski's good name to rejoice in the recognition of his sacrifice for American freedom and liberty," said John White, economic director for the town of Pulaski, in an e-mail. "He was a bit of a rabble-rouser! "en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kazimierz_Pu%C5%82aski

Kazimierz Pułaski (Polish pronunciation: [kaˈʑimʲɛʂ puˈwaski] ( listen); full name: Kazimierz Michał Wacław Wiktor Pułaski) of Clan Ślepowron, often written Casimir Pulaski in English in the USA (March 4, 1745[1] – October 11, 1779), was a Polish soldier, member of the Polish-Lithuanian szlachta and politician who has been called "the father of American cavalry".[2][3]

A member of the Polish landed nobility, he was a military commander for the Bar Confederation and fought against Russian domination of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. When this uprising failed, he emigrated to North America as a soldier of fortune. During the American Revolutionary War, he saved the life of George Washington[4] and became a general in the Continental Army. He died of wounds suffered in the Battle of Savannah.

|

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Sept 23, 2009 19:11:17 GMT 1

Modjeska's Voice' to be performed at the Academy of Music in Northampton Play pays tribute to 19th-century actress

By STEPHEN JENDRYSIK

The Republican, MA

Wednesday, September 16, 2009

During her career, Polish actress Helena Modjeska played nine Shakespearean heroines, Gauthier in "Camille" and Schiller's "Maria Stewart."

In 1883, the year she obtained American citizenship, she produced Henrik Ibsen's "A Doll's House" in Louisville, Ky., the first Ibsen play staged in the United States.

In the 1880s and 1890s she had a reputation as the leading female interpreter of Shakespeare on the American stage.

Her private life was tainted with scandal, her second husband was a political exile, and, for a time, she was barred from returning to her homeland.

She was beautiful, exotic, talented and an international celebrity. In California, she had a town named for her, along with a canyon and the north peak of Saddleback Mountain.

Her California home "Arden" is a national historic landmark. She was the mother of world famous bridge engineer Ralph Modjeski and the godmother to American actress Ethel Barrymore.

Finally, in recognition of her international reputation, a Kentucky candy maker named Busath invented a caramel-covered marshmallow confection he called Modjeskas.

On Sunday, a play about the great 19th century actress will be performed on the stage of the Academy of Music in Northampton - the same venue where Modjeska performed three times in her lifetime.

In 19th-century America, the opera house was the cultural center of the community.

DeGray's Opera House in Chicopee Falls and the Wells Opera House in Chicopee Center were second-tier facilities hosting well-known performers at reasonable prices. Star-studded international acts appeared at the State Theater in Hartford and the Court Square Theater in Springfield.

************ ********* ********* ********* ***

A slice from the life of a Polish diva

Kathleen Mellen

Daily Hampshire Gazette

9/17/09

Many a famous performer has graced the stage of Northampton' s Academy of Music: Sarah Bernhardt, Elizabeth Taylor, Harry Houdini, Mae West, Ethel Barrymore, Lillian Gish and Helena Modjeska.

Wait. Who?

Helena Modjeska, the Polish-born actress doesn't appear on the roster of stars listed on the Academy's Web site, but, in her day (late 1800s) she was as popular as any of the other luminaries who appeared on the stage.

The Academy, which opened in 1891, was one of dozens of stages across the country on which Modjeska performed, but it is just one of a very few that still remains in operation.

Sunday, on the 100th anniversary of Modjeska's death, the Polish actress returns to the Academy in the form of Amherst actress and musician Ann Maggs, who will pay tribute to the star in one performance only of the new, original play, "Modjeska's Voice," which Maggs wrote, and in which she stars as the Polish actress.

The nearly one-woman undertaking (Maggs' husband, Walter Carroll, appears in a number of small roles throughout the play) has been 10 years in the making. Maggs first started doing research for the projeducational and cultural relations between the United States and Poland.

A long, full life

Even though Maggs agreed in principle to pursue the challenge, it wasn't an easy task, she says. Modjeska's professional life was long and full and Maggs says it was hard to focus on the essence of that history for a stage performance.

"There's so much to write," Maggs said in a recent interview. "How do you do this?"

But, over time, she discovered a way. Using primary sources such as letters, journal entries and newspaper accounts from the day, Maggs has created the two-act play, with music, that introduces Modjeska at an imaginary time near the end of her life when she decides to revisit some of the sites of her earlier stage triumphs - including the Academy of Music - in which she recounts moments from her life and her performances. She had 35 plays in her repertory and gave nearly 6,000 performances (often two different plays in a single day) in her 30-year career.

At the Academy, her performance in Shakespeare' s "As You Like It" in 1894 earned her a review in the Hampshire Gazette that noted: "Modjeska is a great actor ... it is much of a tribute to one's mechanical skill that a woman of 50 years can touch up her eye brows and dress to simulate the look of 20 years, and quite a little more that she can frisk and spring about the boards with little less than the nimbleness of that youth she imitates." She also appeared in 1899 as Lady Macbeth, and in 1900 in "Much Ado About Nothing."

Her appeal seemed to be in the naturalness of her performances, Maggs said. "Primarily, she acted very naturally, she really understood emotions. One of the lines that I do, 'The best acting I can do is to make people believe that I'm not acting,' was her whole philosophy - to really get into the character," Maggs said. "In those days everything was so melodramatic, chewing the scenery as they say. It was really refreshing."

Modjeska was born in 1940 in Krakow, Poland, when the country was under the rule of Austria, Germany and Russia. She became a well-known actress in Poland before moving to the U.S., where she learned English and continued her impressive acting career, performing with many famous actors, including Edwin Booth, Otis Skinner and Maurice Barrymore, father of Lionel, Ethel and John.

She hoped to return to her native Poland a triumphant success in the U.S., but those plans were thwarted after she spoke out publicly at the 1893 Chicago World's Fair against what she described as the oppression of the Polish people by the occupying countries. Modjeska was forbidden from ever returning to - or performing in - Russian-occupied Warsaw, Poland - an edict that lasted for the rest of her life. Modjeska died in 1909 in California, but is buried in her Polish hometown of Krakow.

Everyone has skeletons

Maggs was well-positioned to create the work of theater. A music librarian at Amherst college, she has a library degree and archival training. In 1994, in a similar project, she wrote and performed a play about Belle Skinner, of the Holyoke Skinner family that owned Wistariahurst. It's a play she's performed annually since at the gracious historic home in Holyoke that is now a museum. She was even invited to perform that role at a Skinner family reunion.

Like her Belle Skinner, "Modjeska's Voice" also comes "from the horse's mouth," Maggs said.

"My primary source was her book, "Memories and Impressions of Helena Modjeska," published the year after her death by her husband. She also drew from letters, diaries and journals.

The play, which received partial support from the Northampton Arts Council, presents vignettes from Modjeska's life and from her performances and includes music. Modjeska often sang on the stage, sometimes accompanying herself on the piano. Maggs, an accomplished vocalist and pianist, will do the same.

During her decade of research, Maggs found plenty to write about that, she says, will engage and entertain audiences interested in drama, history and Polish culture.

For example, Modjeska introduced Henrik Ibsen's "A Doll's House" to this country. "They didn't like it," Maggs said. "She did it down in Kentucky. The audience said, 'No, it's a little too edgy.' " She wrote a children's book and illustrated it, Polish on one side, English on the other, which is in the Museum of the City of New York.

In true star mode, Modjeska traveled from performance to performance in a private railroad car. "She was the first actress to have one because she had all these one-night stands," Maggs explained. In fact, she says, on one occasion when she was performing with Maurice Barrymore, she invited the famed actor to share her private car. But, Barrymore's wife said, "Absolutely not. I'm going to be there too." But, you won't hear much about such peccadillos in Maggs' play.

"There were little intrigues, I don't bring them out, I don't dwell on them," Maggs said. "This is a choice. ... How much do you tell? I don't go into sordid details. Everyone has skeletons in the closet."

Maggs, who is Polish-American, does turn her gaze to the pivotal moment at the 1893 World's Fair when Modjeska spoke out against what she saw as inhumane treatment of Poles by the occupying countries. Modjeska used her famous voice to speak for them, Maggs said - telling her audience, "As long as there's one Polish woman alive, Poles will not die."

"Her whole life was to try to get human rights for Poland, to get Poland recognized," Maggs said.

It was as much that moment in history as any on stage that convinced Maggs to create this piece to honor the actress.

"I'm Polish-American, " Maggs said. "When I first found out about the situation of Poland, I thought I really should do this for myself, for my family.

Ann Maggs performs "Modjeska's Voice: The Actress Returns to the Academy of Music," Sunday at 3 p.m. at the Academy of Music, 274 Main St., Northampton.

Advance tickets costing $12 for general admission and $15 for priority seating are available at State Street Fruit Store in Northampton, Odyssey Bookshop in South Hadley and the Jones Library in Amherst. Tickets at the door cost $15 for general admission and $18 for priority seating.

For ticket information, call 594-9623 or 532-1564 or visit ictheatre. tix.com/Event. asp?Event= 215766. For other information, visit www.modjeskasvoice. com.     en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Helena_Modjeska en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Helena_Modjeska

|

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Oct 2, 2009 22:08:59 GMT 1

Marek Edelman, the man who could be my authority, is dead.

Marek Edelman (born 31 December 1922 - died 2 October 2009) was a Polish political and social activist, cardiologist, and the last leader of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising of 1943. Died on 2nd October 2009 in Warsaw.

Life

Marek Edelman was born in 1919 in Homel (now Belarus) or in 1922 in Warsaw into a Polish-Jewish family. Died on 2nd October 2009 in Warsaw. His mother, Cecylia Edelman (died 1934), was a Bund activist. As a child, Marek Edelman was a member of the Socialist Children's Association (Socjalistiszer Kinder-Farband).

In 1942, as a Bund youth leader, Edelman was a founder of the underground Jewish Combat Organization (Żydowska Organizacja Bojowa). In the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising of April–May 1943, led by Mordechai Anielewicz, Edelman became one of the three sub-commanders, and the leader after the death of Anielewicz. Edelman survived the suppression of the uprising and the Ghetto's liquidation and managed to escape, aided by Polish underground activists of Armia Ludowa (the People's Army). He later joined the Polish underground Home Army and in the summer of 1944 participated in the Warsaw Uprising.

After World War II, Edelman studied at Łódź Medical School. In 1976 he became an activist with the Workers' Defence Committee (Komitet Obrony Robotników) and later with the Solidarity movement. Under martial law in 1981, he was interned. He took part in the Round Table Talks and served as a member of the Sejm (parliament) from 1989 to 1993.

On 17 April 1998, Edelman was awarded Poland's highest decoration, the Order of the White Eagle.

In the summer of 2007, an Israeli youth group came to Łódź to film documentaries with a group of Polish youth. One of the films was about Marek Edelman, and emphasized that the Israeli youths had never heard of Edelman, apparently because he had been anti-Zionist. During the filming, the group interviewed Edelman[citation needed].

Marek Edelman was married to Alina Margolis-Edelman (1922-2008). He lived in Łódź. |

|

|

|

Post by valpomike on Oct 2, 2009 22:27:47 GMT 1

He looked to be a great man, who we do not have many of any more, I am one of the last few. I did not know of this man, so, thank you for the information on him.

Mike

|

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Oct 10, 2009 20:50:39 GMT 1

House agrees to make Revolutionary War hero Casimir Pulaski a U.S. citizen

By Sabrina Eaton

The Cleveland Plain Dealer

October 08, 2009

WASHINGTON — The House of Representatives voted unanimously today to grant posthumous U.S. citizenship to Polish-born American Revolutionary War hero Casimir Pulaski, who was killed at the Battle of Savannah in 1779.

"It is my sincere hope that Brigadier General Pulaski will not have to wait much longer before he is bestowed with the honorary citizenship he so deserves for his sincere commitment and ultimate sacrifice for freedom for the people of the United States of America," said Cleveland Democratic Rep. Dennis Kucinich, who authored the resolution and is working with Illinois Democratic Sen. Richard Durbin to get the measure through the U.S. Senate.

Pulaski emigrated to the United States and joined the American Revolution after serving in several Polish revolts against Russian domination.

He saved George Washington's life in battle, and went on to form the Continental Army's cavalry division. He has been lionized by Polish-Americans. Numerous landmarks around the country are named in his honor.

Toledo Democratic Rep. Marcy Kaptur was among several Polish-American members of Congress who spoke in favor of the resolution on the House floor.

"He should be recognized permanently by the nation that he helped to create and to defend in a singularly noble undertaking, " Kaptur said.

|

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Nov 5, 2009 21:54:21 GMT 1

Alexandra Golota and Ania Bilinska read fragments of "The Peasant Prince" as part of the Kosciuszko Foundation's celebration of its namesake's name day.

A blue sash to honor a Polish hero, Poland's triumphs

by Justine Jablonska

Medill Reports

Oct 29, 2009

Virtuti Militari medal

Courtesy of the Polish Museum of America

A Polish Virtuti Militari medal, an order of merit created by the Polish king in the early 1790s.

Polish dancers

Justine Jablonska/MEDILL

Members of the Polonia Dance Ensemble wear white dresses with blue sashes and hair ribbons to commemorate Kosciuszko's name day.

Tadeusz Kosciuszko – sound familiar?

Maybe not, even in Chicago despite its large Polish population and a public school calendar that includes a day off for the birthday of a fellow Pole, Casimir Pulaski, who fought in the American Revolution.

But on Wednesday, members of the Kosciuszko Foundation celebrated the memory of this revered Polish hero, a man who played a vital role in the American war against the British. Foundation chapters throughout the U.S., including Chicago, had special programs devoted to Kosciuszko.

For Chicagoans, Pulaski may be the more familiar name, but in historical terms, Kosciuszko's achievements were much more significant in the war for independence.

Kosciuszko was born in 1746 and was intimately involved with such iconic moments in American history as the creation of West Point and the treason of Benedict Arnold.

Hailed as a brilliant Polish military strategist and engineer, he was also a staunch believer in social justice at a time when much of Polish high nobility had serfs and American colonists had slaves.

Thanks in part to Kosciuszko, the U.S. won its independence.

"Kosciuszko came up with the battle plan for the Battle of Saratoga," said Alex Storozynski, president and executive director of the Kosciuszko Foundation. "He was the chief strategist."

That battle in upstate New York in fall 1777, Storozynski said, was the turning point of the American Revolution – and the first battle the Americans won. During the war Kosciuszko spent more than two years years designing and building West Point, the most significant fort in American colonies at the time, Storozynski said. It would become the site of the West Point Military Academy.

As for Benedict Arnold, his treasonous act involved trying to sell Kosciuszko's plans for the fort to the British, Storozynski said.

Storozynski is the author of "The Peasant Prince: Thaddeus Kosciuszko and the Age of Revolution," which was released in April. While researching the book, he learned about a touching event held in a Polish palace in 1792 to honor Kosciuszko. Tragically, at that time, Poland had waged – and lost – a war for its own independence. The war pitted Poland against the combined forces of Russia, Prussia and Austria. The precipitating cause was the Polish Constitution of 1791. Having lost the war, Poland would cease to exist as an independent nation until the end of World War I.

"This constitution went too far and too fast in providing freedom and civil rights for everyone,"

Storozynski said. As a result, Russia, Prussia and Austria attacked Poland to "stop these democratic reforms."

That same year, the Polish king created an order of merit honoring Polish soldiers who fought in the war. But the new government demanded that the soldiers discard their medals, Storozynski said. The soldiers complied but sent the blue ribbons from these medals home to their wives and girlfriends.

On October 28, 1792, a Polish prince held a party in honor of Kosciuszko. It was his name day, an event considered as important as a birthday. The female guests wore white dresses with blue sashes and blue ribbons in their hair as homage to those lost medals.

The Chicago chapter recreated this event at the Polish Museum of America on Wednesday evening. It honored Mariola Golota, a general practice attorney in Chicago, whose daughter Alexandra was a debutante at the annual Kosciuszko Foundation Ball in New York in April. She was the first Chicago chapter debutante to participate in the Ball.

At Wednesday's event, Alexandra, a Marquette University student, read fragments of "The Peasant Prince." She was joined by Loyola University student Ania Bilinska. Both wore white dresses, and Bilinska's included a light blue sash.

Kosciuszko is part of her "list of prominent Polish figures," Bilinska said.

"He's also a person I don't hear very much about in America, even in Chicago," she said, "which is upsetting sometimes because he was very important."

John J. Kulczycki, professor emeritus of Polish history, was among the 60-some guests attending the event.

"Kosciuszko is one of the authentic heroes of Polish history," he said.

A professor at UIC for 23 years, Kulczycki said he shares many of Kosciuszko's ideals.

"In one of his statements, he said that he would fight for Poland but not just for the nobility," Kulczycki said. "He appeals to my own principles of social justice and equality. It's really remarkable for a man of that time to have those ideals." |

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Dec 28, 2009 1:09:48 GMT 1

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tadeusz_RejtanTadeusz Rejtan (or Tadeusz Reytan in Old Polish spelling) (1742 - 1780) was a Polish nobleman. He was a member of the Polish Sejm.

In September 1773, Rejtan famously tried to prevent the legalization of the first partition of Poland. He is said to have bared his chest and laid himself down in a doorway, blocking the way with his own body in a dramatic attempt to stop the other members from entering (or leaving) the chamber where the debate on the partition was being held. Despite his efforts, the partition of Poland was legalized soon afterwards.

After the partition Rejtan withdrew from political life. According to tradition, he was so distressed with the loss of a part of his homeland, that he lost his senses, and as a result committed suicide.

Rejtan's dramatic attempt to prevent the partition earned him lasting recognition in Poland. He was, and to the present day is being considered a shining example of a patriot. As a result, he became the subject of many works of art, poems, songs and books. The events at the Partition Sejm were most famously depicted by Jan Matejko in his 1866 painting "Rejtan - The Fall Of Poland".

One of the most renowned and prestigious high schools in Warsaw, the "VI Liceum Ogólnokształcące im. Tadeusza Reytana", established in 1905, is named after Tadeusz Rejtan.www.bejka.com/ireland/Rejtan_Upadek_Polski_Matejko.jpg

|

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Jun 6, 2010 23:32:00 GMT 1

Jerzy Popieluszko beatified in Warsaw

06.06.2010 11:40

Father Jerzy Popieluszko, a priest involved with the Solidarity movement and who was murdered by Poland’s communist secret police in 1984, was beatified during an open-air Mass held in Warsaw’s Pilsudski Square.

More than 120,000 pilgrims from across the country came to the capital to take part in the celebratory Mass, led by Papal envoy Archbishop Angelo Amato.

Soon after the Mass began, Archbishop Amato read out the act of beatification of Jerzy Popieluszko in Latin, after which Warsaw Archbishop Kazimierz Nycz read out the text in Polish.

The feast day commemorating the life of Popieluszko will be held on October 19, the anniversary of his death.

The beatification of Jerzy Popieluszko is a “great gift to a great nation”, Archbishop Amato said during his homily to the faithful on Pilsudski Square.

The Papal envoy underlined that Father Popieluszko suffered because he was a faithful servant to the Catholic Church, and who defended his dignity in the name of Christ and the Church, as well as the freedom of those people, who like Popieluszko, were oppressed and humiliated.

The Blessed Jerzy Popieluszko’s mother, Marianna, was present at the Mass. Solidarity trade unionists also attended the Mass, along with 100 bishops and around 2000 priests.

After the Mass, a procession bearing a reliquary of Jerzy Popieluszko is to go from Pilsudski Square to the Temple of Divine Providence in Warsaw’s Wilanow district.www.thenews.pl/national/?id=133001

|

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Nov 6, 2010 23:13:29 GMT 1

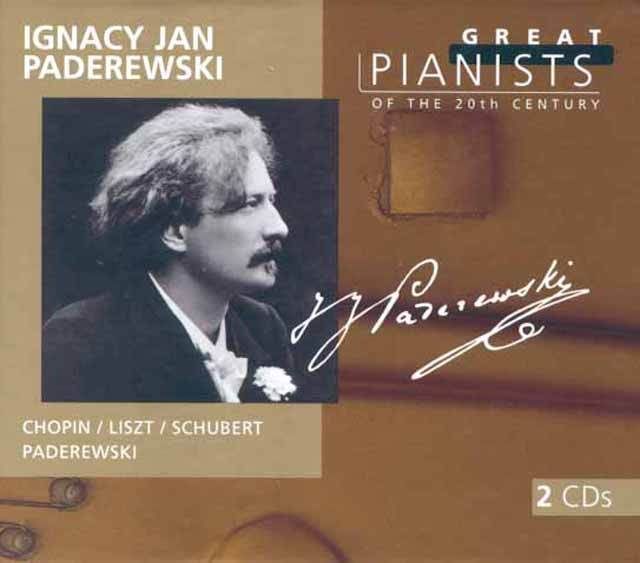

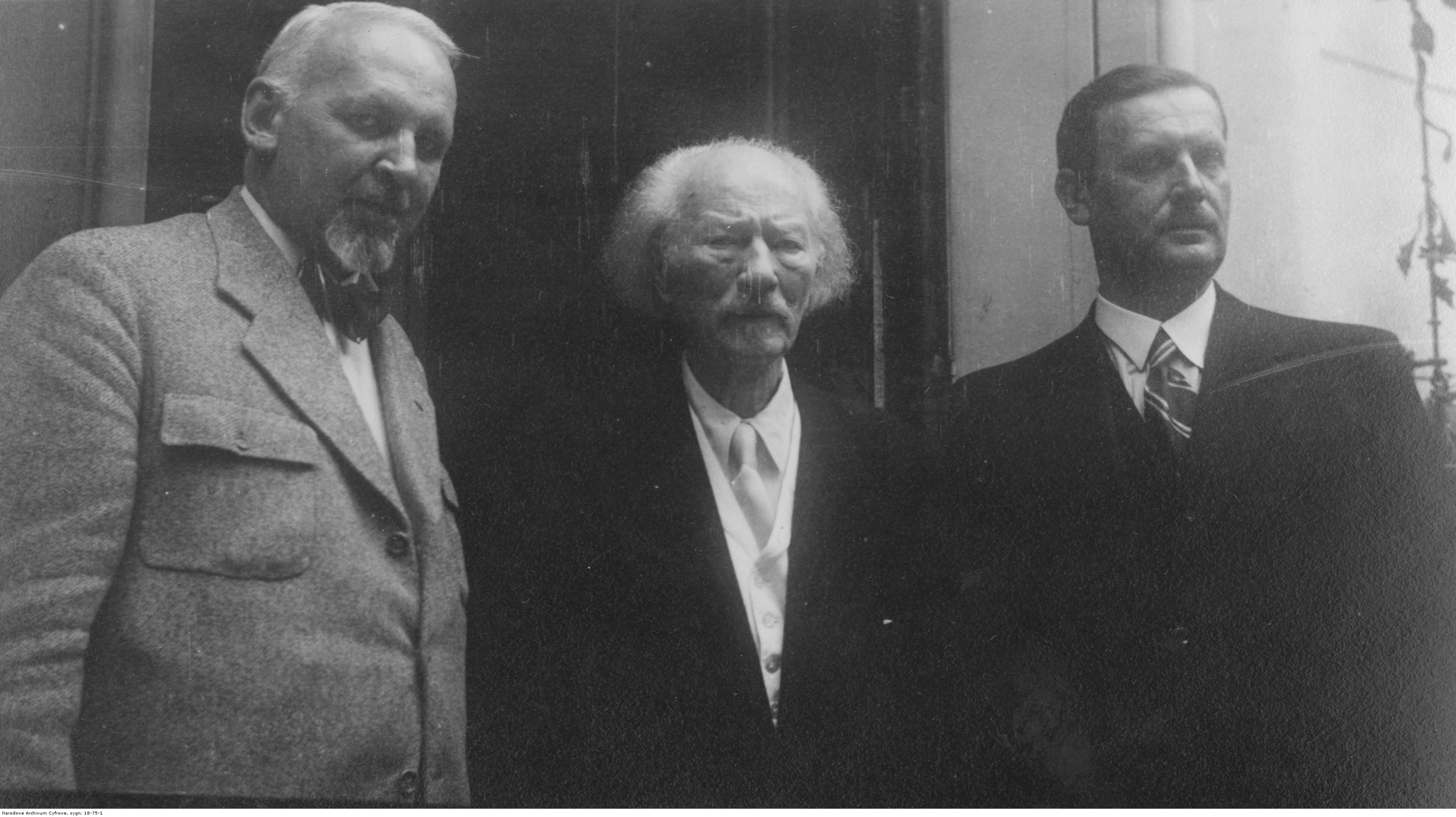

Paderewski remembered

06.11.2010 09:53

Today is the 150th anniversary of the birth of Ignacy Jan Paderewski, musician, politician, statesman and one of the most outstanding personalities in modern Polish history.

The anniversary is marked by special concerts in many Polish towns. The Warsaw Philharmonic Orchestra and Chorus and Polish soloists tonight and tomorrow perform a concert version of Paderewski’s only opera Manru, with Andrzej Straszyński conducting.

This is the first Polish music drama inspired by the music of Wagner. Premiered in 1901 in Dresden, it was in later years performed in Lviv, Prague, Zurich, Nice, Monte Carlo, Bonn, Warsaw and Kiev, Philadelphia, Boston, Chicago and New York. It has remained until today the only Polish work produced at the Met.

Paderewski was a statesman, orator, intellectual, composer and – above all – one of the most famous and popular pianists of all times. The American president Franklin D. Roosevelt called him a ‘modern immortal’.

As a virtuoso he was adored not only by the greatest celebrities of his time, but by people from all walks of life. He travelled all over the world, attracting the largest crowds in history. One of the reasons for his popularity was his magnificent physical appearance. His long, red hair inspired admiration and awe and many musicians tried to emulate him, wearing the top hat, long coat and long hair. However, the main reason for his fame was his magnificent playing. Each recital was a ‘spiritual happening’.

He once said that everything he achieved in music was one per cent the outcome of his talent and ninety nine per cent the result of hard work.

His pianistic career apart, Paderewski devoted much time to composition, primarily with himself in mind as performer of his pieces. The Minuet in G major, included in the first volume of Humoresques, is among the most popular pieces of music ever written, and is naturally something of a Paderewski trademark.

The Sarabande and the Krakowiak fantastique are also excellent flagships of Paderewski the composer. His output also includes Variations in A major, the ‘Polonia’ Symphony and a piano concerto.

Paderewski’s friendships with many of the leading statesmen of Europe and America paved the way for his political activity. He fought for the Polish cause and became an authority on Polish issues. As Poland's Prime Minister, he signed the Versailles Peace Treaty.

Thus, a pianist's hands helped shape a new Poland, which emerged as an independent state after over 120 years under foreign rule. At the end of the First World War the Big Four (Wilson, Clemenceau, Lloyd George and Orlando), wrote about Paderewski in a joint letter: “No country could wish for a better advocate.”

Paderewski died in the United States in 1941 and was buried at Arlington Military Cemetery in Washington. In 1992, at the request of President Lech Wałęsa, his remains were brought to Poland and buried at St John’s Cathedral in Warsaw.        ![]() [/img]

|

|