|

|

Post by Bonobo on Nov 26, 2017 15:06:02 GMT 1

|

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Nov 26, 2017 16:53:34 GMT 1

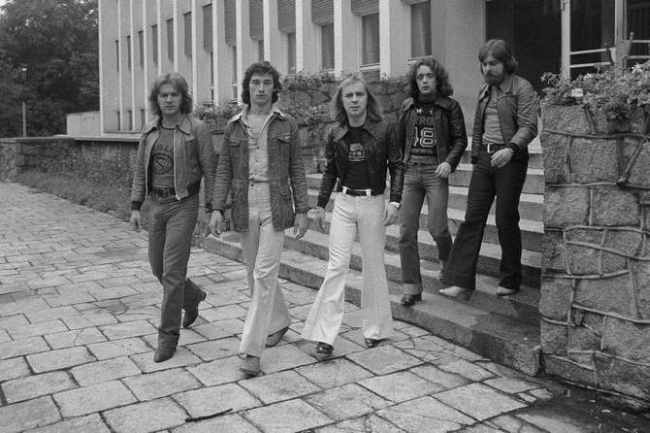

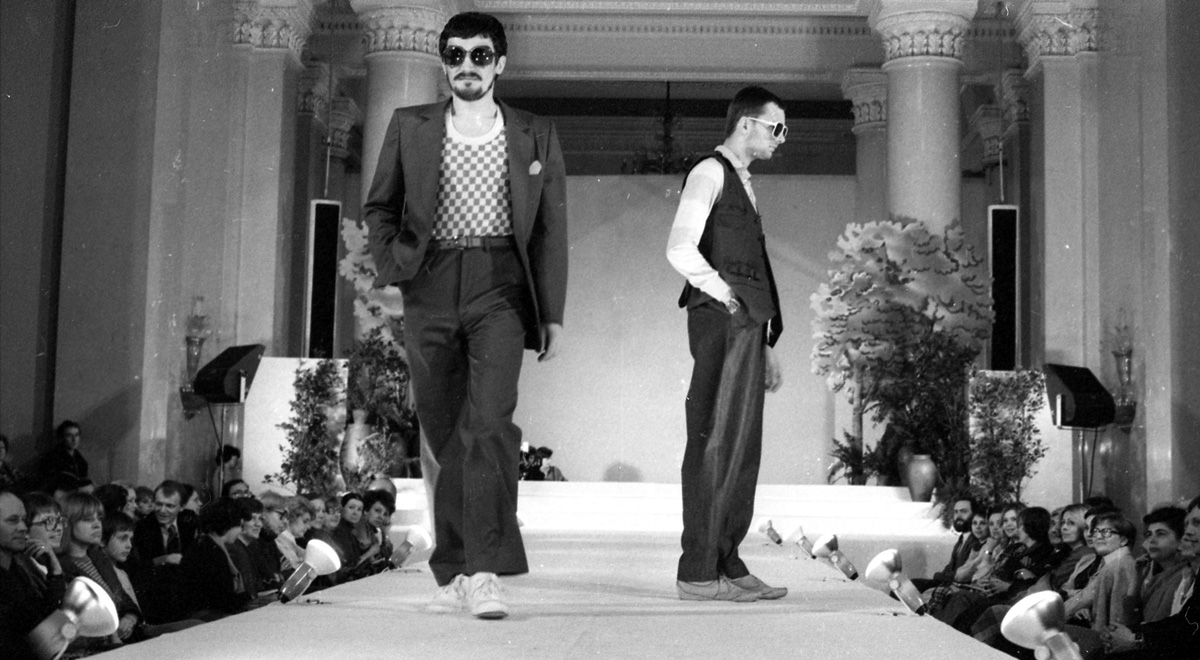

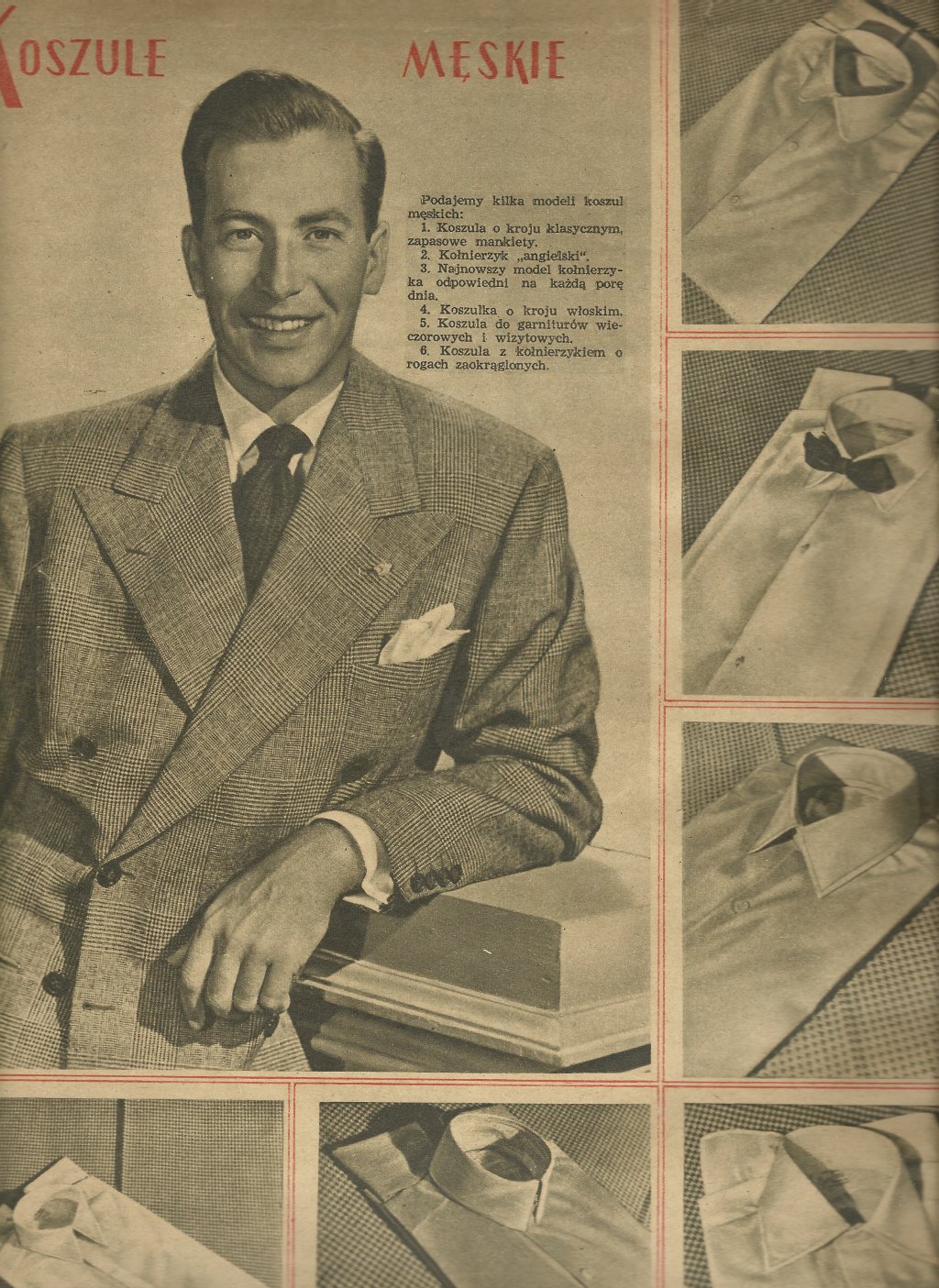

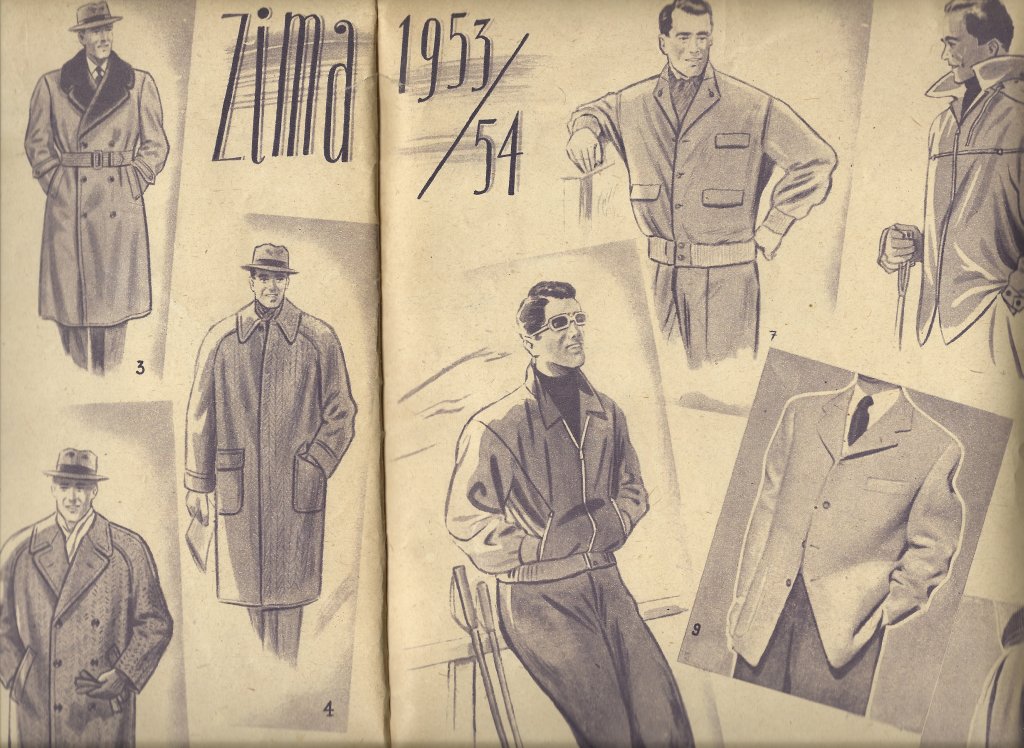

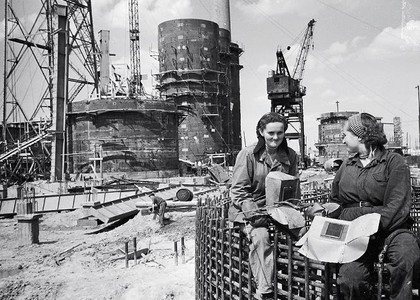

Despite hard times and shortages, urban women made wonders to look attractive. Some men, too. Talented tailors and tailoresses were worth their weight in gold. Fashion in communist times ![]()                               That is incredible, they allowed to publish fashion magazines even in dark Stalinst times       [img src="  " alt=" "] A series of good articles culture.pl/en/article/fashion-in-poland-after-world-war-iiculture.pl/en/article/vintage-polish-fashion-divas-of-the-1950s-and-60sculture.pl/en/article/grace-under-pressure-fashion-in-the-peoples-republic-of-polandculture.pl/en/article/fashion-lessons-from-communist-polandFashion in Poland after World War II

User Culture.pl's picture

Culture.pl

2016/08/04

…Between Paris and Moscow, between the silhouettes of the West and the dies of the East, between dreams and poverty, war order and new systems, conformity and rebellion.

When the female citizens of Warsaw began returning to the capital in 1945, they did so in simple, patched suits, in thick woollen stockings marked with traces of home darning, they carried suitcases that held all their belongings, and wrapped their hair in turbans. Art critic Szymon Bojko noted that that great turban protected hair from the ubiquitous dust in the city. Warsaw was a city of rubble – twenty million cubic meters. The smell was also ubiquitous. There was no soap, no toilets, no drains. Magda Grzebałkowska quotes the memories of Janina Broniewska in her reportage 1945:

Ruin from all perspective. There’s nothing. There’s nothing. Here there’s death.

Festival of Poland’s Rebirth, a party for the people on the sidewalks and squares demolished during WWII, near the ruins of Jasiński’s building at the intersection of al. 3 Maja (today al. Jerozolimskie) and ul. Nowy Swiat, Warsaw, April 1947. Photo from the exhibition New Start: Warsaw 1945-1955, History Meeting House; photo: PAP/Jerzy Baranowski

Festival of Poland’s Rebirth, a party for the people on the sidewalks and squares demolished during WWII, near the ruins of Jasiński’s building at the intersection of al. 3 Maja (today al. Jerozolimskie) and ul. Nowy Swiat, Warsaw, April 1947. Photo from the exhibition New Start: Warsaw 1945-1955, History Meeting House; photo: PAP/Jerzy Baranowski

Anyone who returned to Warsaw could report to an office and get a one-time allowance of 500zł. In January 1945, one pair of rayon stockings cost 800zł. It seemed that fashion would never return. Poland was in ruins and there was no place for such trivial concerns. The 14 July 1945 issue of Przekroju read:

For heaven’s sake, ladies, see to something else! No one, after all, looks nice. But really, you cannot waste too much time on it, when there are so many important things to do.

But just two months later a ‘Fashion’ section appeared in the magazine and stayed there permanently. The first text was an invitation for fashion to return and a witty manifesto.

Women should be pretty. She should not dedicate half her life to this, but about 1/10th. As much as is normal for men to spend on bridge. Then the world will return to balance and everyone will be happy.

And the world really did find balance – thanks to the needs of fashion and self-care. The capital came alive. The bazaar flourished. Among the ruined homes, in courtyards and non-existent intersections, there started to appear hastily constructed metal boxes advertising ‘Pedicure, Manicure’. Pre-war fashion houses reappeared – shoemakers, stocking makers, tailors, and dressmakers. Advertisements popped up in newspapers telling customers that a plant had survived, or had moved or been renamed. ‘Eternal perm. Guaranteed, formerly at 19 Wolska, now 4 Sewerynów’.

The city’s shopping centre stood at the junction of Al. Jerozolimski and Marszałkowska. At that time, a private boutique, ‘Feniks’, was opened by Jadwiga Grabowska at the corner of Marszałkowska and Koszykowa. Grabowska later became one of the most important figures in fashion design during the era when Poland was under communism. She explained:

I called the workshop ‘Feniks’ [trans. Phoenix], as it was reborn in this poor, ashen, burned Warsaw.

Within a few years, most boutiques were liquidated or nationalized. Feniks, however, began the story of haute couture, which survived the era in which Poland was under communism.

A few years ago, renowned photographer Andrzej Wiernicki recalled being sent to photograph the boutique for Express Wieczorny on his first fashion job. He had no concept for the shoot and had replaced a sick colleague. He heard from the editorial board that it was the first post-war fashion salon – real fashion, ‘not for communists’. He was curious. Years later, he asserted:

Without Jadwiga Grabowska there would not only be no Polish Fashion, but no post-war Polish fashion at all.

After the war, fashion began to return, not only through the boutiques, but also via fashion shows – then called ‘reviews’. They appeared as early as the spring in 1947. When Christian Dior amazed Parisians with the ‘New Look’ – a new ‘A-line’ silhouette that required a dozen meters of fabric to sew a skirt – in Poland, fashion was still coloured by crisis, austerity, and the hardened everyday of war.

Fashion looked to ‘alteration’ – or, as we would say today, ‘recycling’. As described in the press, this ‘creative processing’ aroused the greatest admiration among smart dressers. A journalist in the popular weekly Fashion and Practical Life reported on a fashion show:

The alterations were so beautiful in a harmonious combination of colours, seams, sewing, and lacing that you suspect fashionistas are ready to make new dresses like these, looking at such creative reuse.

Fashion shows were often accompanied by charity events – for example, to collect money for orphans.

The time of war and post-war reconstruction were one of shortage, debris, substitutions, and erasures. When clothes were to be finished after years of everyday wear in a time of war and there was no prospect for anything new, one had to – as was often repeated – ‘somehow make do’. To be fashionable, one often had to look for inspiration outside of their existing wardrobe. Enterprising women sewed with curtains, tablecloths, and blankets, and adorned caps and boots with felt flowers. Every woman sewed. In New Warsaw Courier an article read;

In every house there are old, threadbare sweaters, worn-out pullovers, scarves, etc. They lie forgotten and eaten by moths. Meanwhile, with good intentions and some work, we can refresh, modernize, and make them useable again.

Men’s wardrobes also became a source of inspiration. Men – in the army, sent back from forced labour, fighting with partisans – left behind closets full of clothes. Women fighting on the home front, behind the scenes of war, used these found materials to sew new coats and dresses. After the end of occupation, black outfits were in fashion and known as ‘English’, as they were made from the suits of visiting men. Magazines noted:

In each closet there hangs, for example, an old tuxedo of the master of the house, who himself wore it to a wedding 30 years ago. It would seem to be such a useless thing, already purposeless, but that is not so. From a tailcoat, waistcoat, and trousers women can make a very nice and stylish outfit. If any women do not live in a house with an old tuxedo, no need to worry, just refashion any clothing your husband no longer wears.

Fashion can not only defend against war, but can also use the materials of war. Many elegant women recycled parachutes into blouses and dresses. They offered thin, closely woven silk, then later nylon. At the end of the war, the British began to use excess materials in wedding dresses, and after the war, surplus parachutes reached Poland.

Modest clothing resources reached Poles from the charity work of the United Nations and UNRRA (Organization of the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation). These were not, however, straight from Paris runways, but more typically khaki, jackets with epaulettes, parkas, green military sweaters, and wool ties. This military style became fashionable for men. It is impossible to talk about the reconstruction of cultural masculinity after the war without mentioning Zbigniew Cybulski, who appeared in Ashes and Diamonds wearing a jacket from UNRRA, or Marek Hłasko, who wrote about how, thanks to his M-65 military jacket, he became the most handsome guy on the block.

Women had to learn how to creatively reimagine this military clothing. It became popular to carry military bags and wear military style suits and even altered military coats. Fortunately, aid packages occasionally included dresses – these were the dream: full skirts, round hips, narrow waist, and fitted sleeves. Most fashionable women in the 1940s, however, had to settle for combining: sew a dress from the donated package, or a gown? Many tried to recreate in their dressing rooms some pre-war elegance.

Rylska advises diamonds, and Lucynka sense

Hence, a lot of evening dresses were reminiscent of styles of the 1930s. Even the magazine Przekrój was not sure how the new Polish woman was to dress. Initially there was a character – dubbed ‘the patron Rylska’ – who tried to restore old manners and customs, and jokingly noted that ‘a Christmas gift must come from the heart, even if it is a modest diamond ring’. Such refinement, however, only found a place in jokes.

Every day, although they fed their eyes on reprints of foreign fashion magazines, women chose practical clothing. They did, however, look forward with hope – and sewed themselves dresses with cheap viscose rayon. This material was available to everyone, and the grey streets flourished with women’s wardrobes, which influenced fashion designers and offered evidence of bourgeoning spring optimism.

Soon, it turned out, that a completely different fashion than anticipated arrived in Poland. In the late 1940s, communism claimed fashion as one of the areas of aesthetics and everyday life in which the spirit of socialist realism was to be expressed. From that point on, fashion was to be modest and asexual. Feminine silhouettes were made more masculine; blouses were buttoned to the neck, hips widened, and heads flattened by berets or caps.

Przekroj’s ‘Rylska’ had been silenced. By 1949, in her place appeared ‘Lucynka and Paulinka’, who looked to bring ‘common sense’ to ideas and fashion trends. While the flighty Paulinka always wanted to buy and delight in fashion, the practical Lucynka constantly reminded her that functionality and efficiency are what matter. The ‘fashion bourgeois’ pushed towards constant consumption, but Polish citizens were to value practicality above all else – even if the aesthetics of the ‘shock workers’ disgusted them.

Olgierd Budrewicz mocked Jadwiga Grabowska’s ideas about fashion in Bedeker Warszawski. He claimed that her version of elegance wasn’t for everyone.

In shop windows and showcases are a few examples of dresses and coats that cost several thousand zlotys. From time to time a normal woman runs the risk of wandering into the showroom – and almost always leaves broken and bitter. Only the wives of diplomats and the Life photojournalist Lisa Larsen leave standing tall.

This shift in fashion began with a three-year plan for the economic reconstruction of the country (1947-1949), whose slogans ‘raise the standard of living for workers’ or ‘socialization’ in practice meant simply the nationalisation and centralisation of control of all forms of private property. This mainly affected large enterprises; private craftsmen and tailors survived. They would be the ones who supplied the youth with new fashions. People often were seen peering into the tailor shop with their purchases from the state fabric market. Efforts were made to cover up what was obvious to everyone – poverty. The image of a dazzlingly beautiful socialist women and her handsome lover were nothing more than an illusion created for films such as Adventure in Mariensztat. Everyday ordinary people still wore repurposed clothes, made from what was at home, supplemented with ‘national products’ that were of poor quality and drab colour.

Beatniks and kittens buy junk

Tadeusz Rolke, advertisement for the Smyk Department Store, 1960; photo: Taduesz Rolke / Agencja Gazeta

Tadeusz Rolke, advertisement for the Smyk Department Store, 1960; photo: Taduesz Rolke / Agencja Gazeta

With the first post-war generation, however, there developed dreams of a different story, with different colours and different ideals. From that generation – even before the International Youth Festival in 1955 – emerged the first youth countercultures in Poland under communism – beatniks (bikinarz) and kittens. This generation rushed to new markets – ‘Różycki’ in Warsaw and ‘na tandetę’ (‘for junk’) in Kazimierz in Kraków. Of the market in Warsaw, Agnieszka Osiecka wrote that it served as the ‘Great Therapist’ to the Polish soul – it let them rewrite the trauma of scarcity and deprivation.

Bikiniarz - kolorowe skarpetki i krawat, fot. F.Koziński. Reprodukcja FoKa/Forum

Beatniks – colourful socks and ties; photo: F. Koziński, reproduction: FoKa/Forum

The beatniks loved everything that seemed American and associated with jazz. They wore big coats, cropped narrow pants, platform shoes, flat caps, colourful ties with bold patterns, and striped socks, which became a symbol of this group – partly thanks to the famous representative of the culture, writer Leopold Tyrmand.

The female beatniks – ‘kittens’ – favoured the fashions of American teenagers. They liked hoop skirts, tight sweaters, colourfully patterned blouses, and teased their hair into ponytails or ‘elaborate chaos’. Camel cigarettes, sunglasses, and dark eye makeup in the style of Hollywood femme fatale Rita Hayworth were also quite popular.

‘Kittens’ and ‘beatniks’ had decidedly negative connotations – it was several year before these girls and their icon Brigitte Bardot appeared on the cover of Przekroju.

Many magazines continued to repeat the mantra that bourgeois fashion was uncomfortable, immoral, and wanted to rule the wearer. Socialist fashion, in contrast, was celebrated as comfortable, natural, body friendly, and above all, as catering to the needs of the user and wrinkle-free.

Poles after the war had to constantly manoeuvre between Paris and Moscow, between the silhouettes of the West and the dies of the East, between dreams and poverty, war order and new systems, conformism and rebellion. Post-war fashion in Poland continued to fight – first for its right to exist, and then over its identity.

|

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Nov 26, 2017 17:09:00 GMT 1

|

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Nov 26, 2017 17:23:48 GMT 1

|

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Dec 30, 2017 14:45:44 GMT 1

|

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Dec 30, 2017 15:32:42 GMT 1

|

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Dec 30, 2017 15:46:08 GMT 1

|

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on May 2, 2018 19:33:28 GMT 1

|

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Jun 22, 2019 13:09:22 GMT 1

|

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Dec 5, 2019 22:31:13 GMT 1

|

|

|

|

Post by naukowiec on Dec 6, 2019 23:26:42 GMT 1

Really interesting pics! I still remember special lamps in which you put an egg ( a few at a time) to check if they were fresh. I'm intrigued. The lamps had liquid in? Water? |

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Dec 7, 2019 22:08:17 GMT 1

I'm intrigued. The lamps had liquid in? Water? No, why water?   They were simple lamps to see through eggs if they weren`t rotten inside. I used it once in my life - at a sports camp we went to a local shop and, despite having full board in a local restaurant, bought our own food coz were were always hungry after strenuous trainings. Now I can read such lamps are still used by egg producers.   |

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Dec 7, 2019 22:10:57 GMT 1

I have presented a few main aspects of life in communist Poland and have no idea what else I could show. Any suggestions?

|

|

|

|

Post by naukowiec on Dec 8, 2019 10:10:34 GMT 1

Don't laugh, but I had visions of those 70s style lava lamps in my head for some reason. If eggs are fresh, they will sink in water, and float if they're old. Now I know exactly which type of lamps you are talking about! Tricky. I probably know as much as the average person about life under communism. My biggest surprise from the pics you posted was the contrast in the amount of food available in the shops, but as you explained, sometimes there was more food available, just that no-one had any money. Unless you had connections. Or foreign currency to spend in the outrageously expensive Pewex shops. But there was a thriving black market for goods, yes? I know that everyone had jobs, media was state controlled, and telephones were not easily available. Tanks in the street when martial law was implemented. Underground clubs playing forbidden music e;g Jazz, and no-one could easily leave the country? Although I am acquainted with someone who moved to Poland from the US to do his medical training at that time. Bizarre! Milk bars! I've been to a few over the years! Not so sure if the iconic scene from Polish film Miś where the cutlery is chained to the table, is based on fact or not............

Strangely, not everyone was happy at the fall of communism. My friend's mother explained that it got much harder for her as she no longer had a job. I don't think she minded it too much, and I'm not sure how badly off they were. They live in the countryside and had a few farm animals. I will ask my friend when I see her, because she does remember some of what it was like to live under communist rule.

Nowa Huta I found an interesting place to visit, but bleak. If I remember correctly, it's one of only 2 planned Socialist Realist cities built. I think the other is, unsurprisingly, in Russia. Not sure if what I've written has been of any help really, but maybe there is something that can be expanded upon. |

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Dec 8, 2019 18:52:10 GMT 1

1 but as you explained, sometimes there was more food available, just that no-one had any money. 2 But there was a thriving black market for goods, yes? 3 Although I am acquainted with someone who moved to Poland from the US to do his medical training at that time. Bizarre! 4 Not so sure if the iconic scene from Polish film Miś where the cutlery is chained to the table, is based on fact or not............ 5 Strangely, not everyone was happy at the fall of communism. My friend's mother explained that it got much harder for her as she no longer had a job. I don't think she minded it too much, and I'm not sure how badly off they were. They live in the countryside and had a few farm animals. I will ask my friend when I see her, because she does remember some of what it was like to live under communist rule. 6 Nowa Huta I found an interesting place to visit, but bleak. If I remember correctly, it's one of only 2 planned Socialist Realist cities built. I think the other is, unsurprisingly, in Russia. 7 Not sure if what I've written has been of any help really, but maybe there is something that can be expanded upon. 1 The shortages appeared in 1950s and from mid 1970s till the end of communism. It means 1960s and early 1970s had quite decent supplies. E.g, workers` revolt of 1970 happened not due to shortages but to huge food price rise which workers couldn`t tolerate. 2. The black market was mainly supplied with items bought in state shops and later sold at much higher prices elsewhere. The regime called it speculation. 3. Studying medicine at a state uni in Poland was much cheaper than in the West so such Am guys coming to Poland were not surprising, I also knew a few during my uni years. 4. Plates and cutlery weren`t chained, it was film makers` imagination, but glasses used in street drink vending machines were chained, indeed. 5. Communism badly affected many people in the sense they didn`t know what to do when their local state factory suddenly went bankrupt. They were helpless, like a wild animal born in the zoo and one day released into the wilderness - no chance of survival. That is why for a few years after 1989 one could see grafitti slogans on walls - communism, come back. 6. International architects who come to Krakow are not impressed by the Old Town as much as by Nowa Huta. There are hundreds of Old Towns in the world but Nowa Huta is the only one.  7. Yes, thanks, I will use some of your ideas. |

|

|

|

Post by naukowiec on Dec 8, 2019 22:11:32 GMT 1

huge food price rise which workers couldn`t tolerate. Inflation was very high at this time I think? Communism badly affected many people in the sense they didn`t know what to do when their local state factory suddenly went bankrupt. Yes, I can imagine it was a time of great confusion for many people, and a very difficult period of adjustment. hundreds of Old Towns in the world but Nowa Huta is the only one I really like Kraków, it was the first place in Poland I visited, but I know what you mean. Although it took me 3 visits before I went to Nowa Huta, too much to see, and I still feel like I've only scraped the surface. Nowa Huta is definitely something different. I can't imagine what it was like to live under communist rule, but I think it's very interesting to read about, so I will welcome more posts in this thread  |

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Dec 8, 2019 22:37:07 GMT 1

Inflation was very high at this time I think? I went to Nowa Huta, too much to see, and I still feel like I've only scraped the surface. Nowa Huta is definitely something different. I can't imagine what it was like to live under communist rule, but I think it's very interesting to read about, so I will welcome more posts in this thread Nope, inflation skyrocketed in 1980s after Jaruzelski`s regime stopped paying off Polish debts. But it didn`t help, quite the opposite, they had to print more and more money to pacify restive workers who didn`t forget Solidarity. Nowa Huta didn`t always look so bleak as you said. Those buildings were bright white right after construction. Life was like everywhere else except that the state supervised almost everything: people were born in state hospitals, they grew up in mostly state-owned background, finished state schools, worked in state companies, started families, had their own kids, became elderly and finally died. They experienced happy and sad moments, little joys and big sorrows or vice versa. Pure human life.   Let`s see some scenes from life in Nowa Huta                                       |

|

|

|

Post by naukowiec on Dec 8, 2019 22:43:51 GMT 1

Hmm, there is so much I don't know about those times..... Those buildings were bright white right after construction. Blimey! Hard to believe when you see them now. The whole place must have looked almost clinical. |

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Dec 15, 2019 0:36:40 GMT 1

|

|

|

|

Post by naukowiec on Dec 17, 2019 21:34:24 GMT 1

Let`s see some scenes from life in Nowa Huta Lots of building work going on! Love the pic with the random cow in....... Very interesting pics, thanks for posting. As one can see - there were no chains Yeah, I guessed that famous scene was most likely exaggerated. Interesting to look at the prices, only 2.40 for a 2 egg jajecznica! Those milk bars look reminiscent of old work canteens in the UK, I used to eat in one many moons ago. Nice that milk bars have survived though and aren't only relics of a bygone age. Some fab cars parked in front of one of the bars too  |

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Dec 19, 2019 22:29:42 GMT 1

|

|

|

|

Post by naukowiec on Dec 21, 2019 10:14:10 GMT 1

Fab cars? No, just plain ones, available to residents of an Eastern block country. I love the style of old cars compared with the cars of today, that's what I meant by fab. Christmas in communist times. Shop windows look a bit spartan in comparison with what one would see today, that's for sure! Still lots of Christmas lights though, and all the families shown have a Christmas tree. I guess I was expecting something a bit gloomier. I remember a friend saying,that if she got presents at all, it would be things like socks. Necessities basically. Tradition hasn't changed though, I noticed the Barszcz with uszka being eaten for Wigilia. LOve that dish  |

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Dec 22, 2019 16:44:43 GMT 1

I guess I was expecting something a bit gloomier. I remember a friend saying,that if she got presents at all, it would be things like socks. Necessities basically. It must have depended on family`s wealth. I never got socks for Santa Claus on 6th December or at Christmas - mostly attractive gadgets and a lot of sweets. |

|

|

|

Post by naukowiec on Dec 22, 2019 21:50:41 GMT 1

mostly attractive gadgets and a lot of sweets. What are the 'attractive gadgets'? I am fascinated! |

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Dec 22, 2019 23:51:11 GMT 1

|

|

|

|

Post by naukowiec on Dec 23, 2019 0:05:37 GMT 1

You did quite well for presents! I especially liked your story about the scuba diver! Probably bought from a Pewex store. I mentioned those stores earlier in this thread, did they sell more or less anything as long as you had hard currency?

|

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Dec 23, 2019 13:53:21 GMT 1

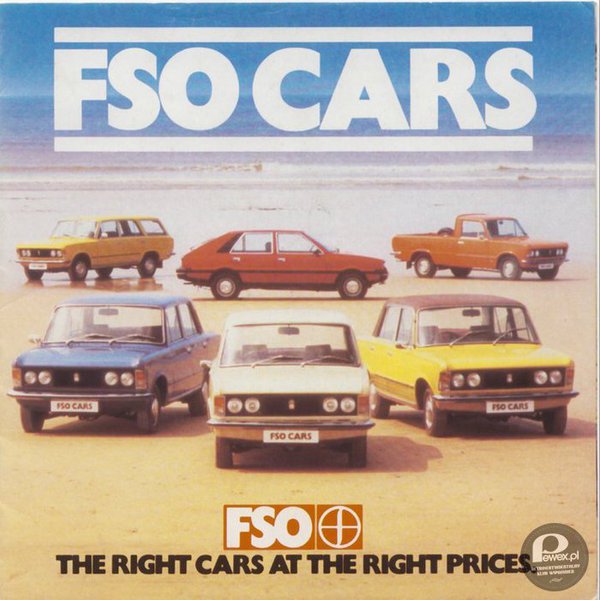

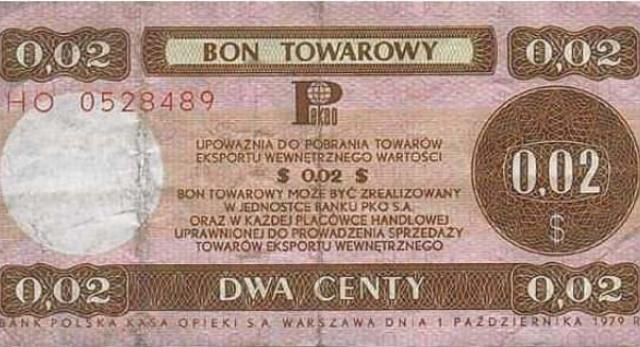

I mentioned those stores earlier in this thread, did they sell more or less anything as long as you had hard currency? Yes, most Pewex stores were small, like a typical grocer`s. However, there were also big ones, like a supermarket. My parents, doing their new flat, rejected Polish made tiles for the kitchen and toilet as too ugly and low quality so they decided to buy hard currency vouchers in the black market and bought nicer Italian or Spanish tiles in Pewex. My sister bought a video set. You could also buy a car there. I knew one dentist who bought a car from Pewex - it was a small Japanese car which cost about 3000 - 4000 $ - incredible sum of money for a typical Pole. But dentists have always been little money machines - not only in the USA/UK.   .            Instead of hard currency, citizens could also pay in Pewex stores with special state vouchers obtained from the state for working abroad or bought at the black market. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bon_Towarowy_PeKaO

Bon Towarowy PeKaO checks were substitute legal tender (complementary currency) used in the People's Republic of Poland. The Polish government, needing hard foreign currency, introduced them in 1960. Citizens of Poland had to exchange foreign currency they had into these notes (bony in plural), issued by the government-controlled Bank Pekao. They were only accepted in special shops in Poland (Pewex, Baltona) where one could buy restricted, imported goods. Outside of Poland, bony had no value and were not regarded as legal tender.

A bon valued at 1 US cent

A bon valued at two US cents

In the 1950s and the 1960s, turnover of Western currency was strictly prohibited, and since January 1960, pre-World War Two currency was purchased by the national bank, which paid for it with bony. Since the 1970s, these regulations were not controlled as strictly as before, which resulted in a flourishing black market of foreign currency. All Polish citizens, who received money orders from the so-called “second payments area” (Polish: "drugi obszar płatniczy"; which covered Western Europe and North America), were not paid in real cash - dollars, pounds or marks, but instead, were issued with bony. This applied to those who received all kinds of payments from the West - salaries, pensions, monetary gifts, grants, donations.

Bon Towarowy PeKaO was used only for purchases at Pewex or Baltona stores, which were controlled by the government. These stores sold imported luxury products, otherwise not available on the market - coffee, chocolate, liquors, household appliances, cars. In the course of time, the bon became the unofficial second currency of Poland, due to rising inflation of the złoty. In the 1960s, the price of one bon was 70-80 złoty, in the 1970s it rose to 150 zł, and in 1981, to 400 złoty. By 1989, the price of one bon was 7000 złoty, and finally, after the monetary reform of Leszek Balcerowicz, the price of one bon (equivalent to one US dollar) was established at 9500 zł. Following the collapse of the Communist system, foreign currency trade became legal, which voided the bony.

Bony were printed in banknotes equivalent to 1 US cent, 2 cents, 5 cents, 10 cents, 20 cents, 50 cents, 1 US dollar, 2 dollars, 5 dollars, 10 dollars, 20 dollars, 50 dollars and 100 dollars. They first appeared on the market on January 1, 1960.  |

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Dec 24, 2019 9:46:41 GMT 1

|

|

|

|

Post by naukowiec on Dec 28, 2019 9:08:58 GMT 1

Wow! It's almost unbelievable to see all the goods in Pewex shops! I don't blame people for shopping in them if they could afford to, but it seems somehow wrong when presumably the majority of people were still queuing for food and toilet rolls! Still, life is sometimes unfair and where there is demand, there will always be supply. I knew one dentist who bought a car from Pewex Were wages under communism as they would be today, in that dentists would earn more than office workers for example? I don't know why, but I always imagined that wages would be similar regardless of occupation, but obviously not if dentists could afford cars!! Sometimes I have crazy ideas! attract people to communism by bigger openness to the West and bought the license to produce Coca Cola in Poland. It seems bizarre to me that Coca-Cola somehow represented openess and was sought after. It's a drink! A symbol of capitalism no less! Poland had its own version too, Polo-Cockta! |

|

|

|

Post by Bonobo on Dec 28, 2019 15:16:32 GMT 1

I don't blame people for shopping in them if they could afford to, but it seems somehow wrong when presumably the majority of people were still queuing for food and toilet rolls! Not people were to blame but the state which wasn`t able to supply basic items to all citizens. Still, life is sometimes unfair and where there is demand, there will always be supply. Supply came from communists who needed hard currency which they always lacked.  dentists would earn more than office workers for example? I don't know why, but I always imagined that wages would be similar regardless of occupation, but obviously not if dentists could afford cars!! Dentists were allowed to run their private surgeries. I remember going to a private dentist as a boy. Why not state clinics? You had to wait long for an appointment and those dentists had lousy equipment and methods. I only went to a state dentist once, during my studies, we all had to undergo official med examination in a state clinic as freshmen. It seems bizarre to me that Coca-Cola somehow represented openess and was sought after. It was communists who banned it, thus creating a symbol of imperialistic capitalism. See the Cold War poster at the top of the previous post. Poland had its own version too, Polo-c...kta! It was created as a much cheaper substitute of Coca Cola and it tasted according to its low price - lousy. One had to be really desperate to drink that.   I drank it once or twice, no more. |

|